Doublets (tables game)

Doublets or queen's game is an historical English tables game for two people which was popular in the 17th and 18th centuries. Although played on a board similar to that now used for backgammon, it is a simple game of hazard bearing little resemblance to backgammon. Very similar games were played in mainland Europe, the earliest recorded dating to the 14th century.

.jpg.webp) Wooden board and counters suitable for Doublets | |

| Other names | Queen's Game, Dublets,[1] Dubblets[2] |

|---|---|

| Genres | Board game Race game Dice game |

| Players | 2 |

| Movement | none |

| Chance | Medium (dice rolling) |

| Skills | pure chance |

| Related games: Spain: Doblet, France: Renette, Dames Rabattues, Iceland: Ofanfelling | |

History

Doublets may be an elaboration of the Spanish game of doblet which is described in detail in 1283 in El Libro de los Juegos published by Alfonso X of Castile.[3]

In 1534, a game called renette or reynette ("little queen")[4] appears in the list of games in Gargantua published by Rabelais. According to Cotgrave's French Dictionary of 1611, renette is "a game of tables of some resemblance with our Doublets or Queenes Game..."[5] The name "queen's game" is recorded as early as 1554[6] and doublets in 1549 in a sermon by Latimer to Edward VI: "they be at their doublets still."[7] Hyde (1694) equates doublets to the French game known variously as tables rabattues, dames rabattues or dames avallées.[8]

By 1621, doublets was clearly well known enough to be mentioned in Taylor's Motto thus: "At Irish, Tick-tacke, Doublets, Draughts or Chesse, He flings his money free with carelessnesse".[9] The earliest known English rules were written down around 1665-1670 by Willughby in his Volume of Plaies, who describes "Dublets" as "the most childish game at Tables in which there is nothing but chance and scarce any skill."[1] He was followed by Cotton, (1674)[2] Seymour (1750)[10] and Johnson,[11] in the various editions of The Compleat Gamester, the later editions being reprints of the first with minor spelling changes.

Equipment

The game is played on a tables board of the type used for backgammon. It has two halves known as tables each of 6 points a side. Players sit on opposite sides of the board and only one table is used. The outermost point on each side is point 1; the innermost, next to the bar is point 6. Each player has 15 counters known as men, one player having white men and the other player, having black ones. Two dice are used.[1]

Aim

The aim of doublets is to be first to play off all one's men.[1]

Rules

The following rules of play are based on Willughby.[1]

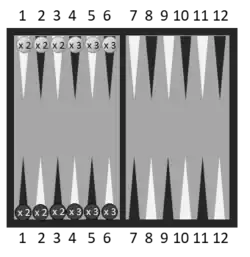

Players begin by dressing the board on the side nearest to them as follows:

- Points 1-3: Two men are placed on each point, one on top of the other

- Points 4-6: Three men are placed on each point in a pile, one on top of the other.

Players throw the dice to decide who goes first. Each player takes a die and throws it. The one with the highest cast wins, picks up both dice and makes the first throw of the game.

In turn, each player throws the dice and moves his or her men based on the result. There are two phases of play:

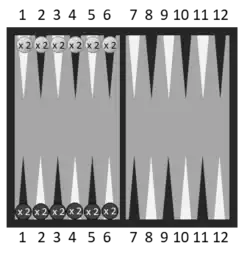

- Phase 1. Players play down a man for each cast of the die. For example, with throws of 2 and 6, the player takes the upper of the two men on point 2 and places it on the same point but above the lower man; they also take the top of the three men on point 6 and place it on the point above the remaining pile of two. If the men on a point corresponding to a die throw have already been played down, the throw is lost.

- Phase 2. When all the men are played down, they are played off or borne off. For example, if a player throws 1 and 5, he may remove a man from each of points 1 and 5. If the point corresponding to a die throw is vacant because the men have already been borne off, the throw counts for nothing.

If a doublet is thrown, the player may play down (in phase 1) or bear off (in phase 2) as many men as the total of the two dice e.g. if two deuces are thrown, four men may be played or borne off; if two fives are thrown, ten men may be played down or borne off. Hence the name of the game.

The first to play off all his or her men wins the game.

Variation

Cotton's description is broadly similar except that, when a player is unable to use the throw of a die, the opponent may use it instead if able. This rule is also found in dames rabattues—see below—but the rules for bearing off in the French variant are different.[2]

Doblet

Doblet is one of 15 games recorded in Alfonso X's book of games. It is simpler than English doublets, but uses three dice.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] There are two players who only have 12 men each and they place them in pairs on the six points on the table of the board nearest to them. Each pair is stacked, one man being placed on top of the other. The players use the same table of the board, so the pieces are opposite one another. The players roll a die each and the one with the higher cast goes first. Again there are two types of move: first players unstack men based on the numbers they roll i.e. a throw of 1, 3 and 5 entitles a man to be unstacked from each of points 1, 3 and 5. Second, players bear off their men based on the throw of the dice. If a player cannot use a throw, the opponent may utilise it instead and may even win in doing so. The winner is the first to bear off all 12 men.[3]

This is "the exact description" of the French game of dames rabattues in Moulidars' Encyclopédie des Jeux (1888) except for the number of men and dice used and their deployment.[12]

Dames rabattues

In France, a very similar game was played, variously called tables rabattues, dames rabattues[lower-alpha 3] or dames avallées.[8] The game is listed by Rabelais in Gargantua in 1534 and extensive rules appear from around 1699 onwards.[13] The following is based on the 1715 compendium published by Charpentier.[14]

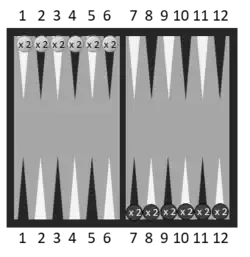

The game is for two players who require a trictrac board, fifteen men each, two dice cups and two dice. Only the half of the board—the table "nearest the light"—is used and the men are stacked as in doublets: two each on points 1-3 and three each on points 4-6, players stacking them on the side of the board nearest to them. Players throw for the lead and the one who throws higher goes first. Players unstack one man per die on the point whose number corresponds to that die. Once all his or her points are unstacked, a player may begin to bear off; again bearing off one man per die on the point corresponding to the throw of that die. The player who is first to bear off all 15 men wins. There are two key differences when compared with doublets. First, a player who throws a doublet keeps the dice and has another throw; this continues until two singles are thrown. Second, if a player is unable to use a die throw, the opponent uses it instead. It is thus possible to win the game on the throw of your opponent's dice. An important exception is that a player who has not yet unstacked all 15 men may not utilise the throw of an opponent who is in the process of bearing off.

Ofanfelling

Ofanfelling or ofanfellingartafl is an "ancient" Icelandic game described by Fiske (1905). In this version, each player has 12 men which they deploy in their right-hand table, stacking two on each point as in Spanish doblet. After throwing to decide who goes first, each player, in turn, unstacks his men in accordance with the throw of the two dice. Doublets entitle a player to another throw and unusable throws do not count. A key difference is that, in phase 2, players re-stack their men on the same point. Finally, there is a third phase in which, once the men are all restacked, they are borne off "exactly as at backgammon"[lower-alpha 4] and the first to bear off all 12 men wins.[15]

Footnotes

- No doublets rule is stated which suggests the name originates in the doubling on men on the points and not a special rule for throwing a doublet.

- The rules make no mention of the number of dice, but the accompanying illustration clearly shows three.

- Spelt "dames rabatues" in older accounts and meaning "unstacked men".

- This is effectively the same as in doublets, since the throw of, for example, a 4, results in the removal of a man on point 4. In backgammon, one would need 4 to get to the end rail and be borne off.

References

- Willughby (1672), pp. 23 ff.

- Cotton (1674), pp. 161–162.

- Alfonso X (1283).

- Fiske (1905), p. 286.

- Cotgrave (1611). Entry for renette.

- Cram, Forgeng and Johnson (2003), pp. 256 ff.

- Fiske (1905), p. 88.

- Fiske (1905), p. 171.

- Taylor (1621), I Care (poem).

- Seymour (1750), p. 248–249.

- Johnson (1754), p. 249.

- Fiske (1905), p. 300.

- Dames Rabattues at Le Salon des Jeux. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- Charpentier (1715), pp. 78–94.

- Fiske (1905), p. 353.

Literature

- Charpentier, Henry (1715), Le Jeu du Trictrac, Enrichi de Figures Avec les Jeux du Revertier, du Toute-Table, du Tourne-Case, des Dames Rabattues, du Plain, et du Toc., 3rd revised, corrected and expanded edn. Paris: Henry Charpentier (1st edn. 1698 - only Trictrac, 2nd edn. 1701).

- Alfonso X (1283). Libro de los Juegos. Seville. MS held in the Escurial, Madrid.

- Cotgrave, Randle (1611). A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues London: Adam Islip.

- Cotton, Charles (1674). The Compleat Gamester. London: A.M.

- Fiske, Willard (1905). Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature: with Historical Notes on Other Table-Games. Florence: The Florentine Typographical Society.

- Forgeng, Jeff, Dorothy Johnston and David Cram (2003). Francis Willughby's Book of Games. Ashgate Press. ISBN 1 85928 460 4.

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. and Will McLean (2009). Daily Life in Chaucer's England, 2nd edn. Westport, CT and London: Greenwood.

- Johnson, Charles (1754). The Compleat Gamester, 8th edn. London: J. Hodges.

- Parlett, David (1999). The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford: OUP.

- Seymour, Richard. The Compleat Gamester, 7th edn. London: J. Hodges.

- Taylor, John (1621). Taylor's Motto: Et Habeo, Et Careo, Et Curo. Edward Allde.

- Willughby, Francis (2003). Forgeng, Jeff; Johnston, Dorothy; Cram, David (eds.). Francis Willughby's Book of Games. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 1-85928-460-4. (Critical edition of Willughby's volume containing descriptions of games and pastimes, c.1660-1672. Manuscript in the Middleton collection, University of Nottingham; document reference Mi LM 14)