Irish (game)

Irish or the Irish Game was an Anglo-Scottish tables game for two players that was popular from the 16th to the mid-18th centuries before being superseded by its derivative, the "faster paced" backgammon.[1] In its day, Irish was "esteemed among the best games at Tables." Its name notwithstanding, Irish was one of the most international forms of tables games, the equivalent of French toutes tables, Italian tavole reale and Spanish todas tablas,[1] the latter name first being used in the 1283 El Libro de los Juegos, a translation of Arabic manuscripts by the Toledo School of Translators.

Tables board from the Mary Rose, contemporary with the game of Irish | |

| Other names | Irish Gamyne, the Irish Game |

|---|---|

| Years active | c. 1507 to mid-18th century |

| Genres | Board game Race game Dice game |

| Players | 2 |

| Movement | contrary |

| Chance | Medium (dice rolling) |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics, counting, probability |

| Related games: Backgammon, English, todas tablas, toutes tables, totis tabulis | |

The name may have been coined to distinguish it from the English Game which was older. There is no evidence that it was particularly linked with Ireland, although it was played there too.

History

Irish gamyne[lower-alpha 1] is mentioned as early as 1507 being played by the Scottish king, James IV,[2] and was a game at which he was apparently a "great hand".[3] In 1586, the English Courtier and Country Gentleman says that "In fowle weather, we send for some honest neighbours, if happely wee bee without wives, alone at home (as seldome we are) and with them we play at Dice and Cards, sorting our selves according to the number of Players, and their skill, some in Ticktacke, some Lurche, some to Irish game, or Dublets."[4] Its popularity in Scotland is reinforced by a poem The Game of Irish by Sir Robert Ayton written in the early 17th century which opens with the line, "Love's like a game at Irish..."[5] Fiske knows nothing of its origin and surmises that it was given the name because it was unlike the familiar game and "as nobody knew whence it came it might as well be baptized Irish as anything else."[6] Hyde calls it tictac seu trictrac Hibernorum without explanation.[6]

By the mid-17th century, it was being challenged by backgammon, although Irish was assessed to be the "more serious and solid game"[7] and "of all games at Tables... the best."[8] In The Irish Hudibras in 1689, a poetic caricature of the rural Irish, we read that "The priests that lodge upon this Common, Do play at Irish and Bac-Gammon..." thus suggesting that the game was also played in Ireland at the time and that, like backgammon, was a favourite pastime of the clergy.[9]

The earliest rules go back to Francis Willughby's manuscript of English games written c. 1660-1677, and a less detailed account in Charles Cotton's The Compleat Gamester which was published in 1674 and reprinted until 1750. Fiske says it was "evidently much played in the 17th and 18th centuries."[6] After that, the game of Irish fell into obscurity apart from the term aftergame which was used figuratively to refer to measures taken after an initial plan had misfired.[lower-alpha 2]

Equipment

Irish was played on a standard tables board. Willughby describes a typical board of two halves, hinged in the middle and divided into four 'tables' each of six points upon which the pieces, known as men move. There are 30 men, 15 for each player in a separate colour, usually black and white. Two dice are used and each player has a dice cup.[8]

Rules

The following rules are based on Willughby except where stated.[8]

Starting layout

Cotton (1674) gives two alternative starting setups:[10]

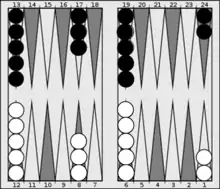

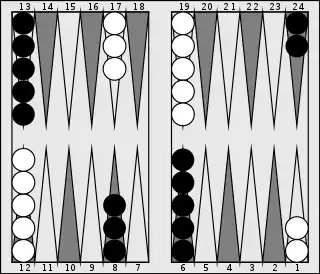

- First variation. This is the same as todas tablas.[lower-alpha 3] Each player begins with all 15 men on the opponent's side of the board: 2 on point 24, 5 on point 19, 3 on point 17 and 5 on point 13.[lower-alpha 4]

- Second variation. This is the same as modern backgammon. If the points are numbered from 1 to 12 on the player's side of the board and 13 to 24 on the opponent's side (see diagram), then each player places 5 men on point 6, 3 on point 8, 5 on point 13 and 2 on point 24.

Willughby only describes the second variation.

Aim

The aim is to move all one's men to the home table (points 1 to 6 for Black and 19 to 24 for White) and then be first to bear them all off.

Movement

The direction of march for each player is from the 24 point to the home point (ace point). Players take turns at rolling two dice. For each die, one man may be moved homewards by the number of points corresponding to that die. Alternatively one man may be moved by the number of points corresponding to the total of both dice, pausing on the intermediate point en route that corresponds to the score on one of them. This is called 'playing at length'.

Players may "play upon any point that has no men upon it" or one that has one or more of their own men. They may also move a man onto a point with only one opposing man, in which case the latter is 'hit' (see below). A point with two or more opposing men on it is blocked and cannot be played upon. To 'play at length', the intermediate point, as well as the destination point, must not be blocked. A player may have any number of men on one point simultaneously.

A player 'takes a point' by moving two men to the same empty point or 'binds a man' when a second man is played to a point already occupied by one of his or her own men. If this is achieved using both dice, it is 'binding at length'.

'Playing at home' or 'playing in one's own tables' means playing men on one's own side of the board.

Hitting a blot

A 'blot' is a single man on a point that is within range of one or more opposing men. It is a 'blot of die' if within 6 or fewer points of an opposing man.[lower-alpha 5]

'Hitting a blot' is when a player moves a man onto an opponent's blot. If this is done on an intermediate point it is called 'nipping a man'. When a blot is hit (or nipped), the man is removed from the board and must be re-entered into the opponent's home table by the number of points on a die throw, e.g. if an Ace is thrown, the man must be re-entered onto the opponent's home point (i.e. Ace point or point 1). If the point is occupied by one opposing man, that man is hit; if occupied by 2 opposing men, it is blocked from entering on that point. Men that are off the board having been hit must be re-entered before any board men may be played. If unable to re-enter, the player misses a turn.

Binding up the tables

Players are said to have 'bound up their tables' when they have taken all their first six points (with at least 2 men each). A player must 'break up the tables' if the opponent has men to be re-entered by removing all men bar one from a point and re-entering them as if they had been hit. This is done by both players throwing the dice; the one throwing the highest total on the two dice chooses which point is to be broken.

Bearing off

Once all a player's men have reached the home table, they may be borne off in the usual way. The first to bear off all 15 men wins the game.[lower-alpha 6]

Tactics

In Irish, the fore game or foregame was the preferred tactic whereby the player, aided by rolling high numbers, played his or her men off the board without having had any of them removed by the opponent. The latter game, also called the back game, after game or aftergame was played if a player rolled low numbers at first and was forced to change his plan by, e.g. leaving blots on purpose in order to encourage them to be hit, so they could be re-entered to impede the opponent's progress.[8]

Backgammon comparison

Historical backgammon

Backgammon, in its earliest version, introduced a number of changes to Irish and subsequently ousted it in popularity during the 18th century.[1] The main differences were:[8]

- Doublets were scored double

- The game could be won double if a) the winning throw was a doublet or b) the opponent still had some men outside the home board

- The game could be won triple if a player bore off all 15 men before any of the opponent's men reached the home board. Cotton called this a Back-Gammon.[lower-alpha 7][lower-alpha 8]

The game was thus faster and higher scoring than Irish.[10]

Modern backgammon

Compared with early backgammon, the modern game has added the doubling cube and introduced further rule changes. The tables board now has a 'bar' and pieces are moved to the bar when hit instead of just being off the table. Winning double is now called a gammon and is achieved if a player bears all pieces off the board before the opponent has borne any. The definition of backgammon has changed and is now scored if a player bears all pieces off the board while the opponent still has pieces on the 'bar' or in the player's home table.

Double-hand Irish

Double-hand Irish was a four-player, partnership game in which the two players of each side threw the dice in succession and the better throw was played. An exception was that, on the first turn, only one player of the team going first, threw the dice. Willughby reckoned that the double-hand game was "duller and worse than the single hand."[8]

Todas Tablas

Irish has been equated to the Spanish game of Todas Tablas,[1] the rules for which appeared in El Libro de los Juegos published in 1283 by King Alfonso X of Castile. [11] By 1414 it had spread to Aragon, where it was one of just three games permitted by the town council of Daroca.[12]

The games uses a standard tables board, albeit with semi-circular cut-outs in the border at the base of each point to hold a circular piece. There are fifteen men per side and two dice. The rules of play are very similar to Irish, but the starting layout is debated since some sources argue that the text does not describe the layout portrayed in the associated illustration, which corresponds to the 2nd variant in Irish described above. Several conclude that it must have had the same starting layout as backgammon; others that the illustration is right.

Alfonso's rules may be summarised as follows:[11]

We are told that Todas Tablas ("all tablemen") is so named because in the setup the men are spread across all four tables of the board.[lower-alpha 9] The game is played on a standard tables board which Alfonso describes as "square" and containing four "tables" each of six points and numbered 1 to 6 from the outside to the centre. There are two dice and two sets of 15 men; the sets being of different colours. The setup in the folio is that illustrated above for variation 1 of the game of Irish.

The men move according to the throw of the dice; each man moving by the number rolled on a die. Players move around the board from their ace point (home point) to their bearing table. A single man on a point is liable to be captured if the opponent is able to move a man onto that point. Men that are doubled up cannot be so captured. Captured men must be re-entered into the home table. Once men reach the bearing table they are borne off.

The prime of tables occurs when one captures so many of the opponent's men that he then does not have points upon which to enter them and thus loses the game. A tie occurs if neither player can move.

Some historical sources have equated Todas Tablas with Backgammon,[lower-alpha 10] but Alfonso's rules describe a much more basic game and the illustrated setup is different.

Footnotes

- Presumably "Irish Gammon" is meant.

- See e.g. Johnson (1818) "Aftergame. scheme which may be laid, or the expedients which are practised after the original design has miscarried; methods taken after the first turn of affairs."

- As portrayed in El Libro de los Juegos, although scholars do not agree what layout the text describes.

- Cotton's account does not make clear which side of the board a player's men are placed, but his subsequent description of play means they must all start on the opponent's side. It may be an older mode of play.

- Presumably only if it is in front of the opposing man i.e. at risk of being hit.

- Neither Cotton nor Willughby describe bearing off in detail, so it is assumed to follow the standard practice of the time, which is also the same as at backgammon.

- Cotton adds that the game could be won quadruple if the winning throw of a Back-Gammon was a doublet.

- Today, a gammon and backgammon are defined slightly differently, q.v.

- Some authors take this to mean that each set of 15 men is divided among all four tables, but this is not explicit nor what the illustration shows. However, the ensuing textual description is confusing.

- For example, Casey (1851), p. 32 and Dufief (1825), p. 198.

References

- Forgeng, Johnson and Cram (2003), p. 269.

- Tytler (1833), p. 342.

- Anon. (April 1833), p. 609.

- Brand and Hazlitt (1870), p. 339.

- Roger (1844), p. 51.

- Fiske (1905), p. 159.

- Howell (1635), Vol. 2, No. 68.

- Willughby (2003), pp. 123-126 (folios 37-43).

- Carpenter (1998), p. 44.

- Cotton (1674), pp. 154–155.

- Alfonso X (1283), fols. 77v and 78r.

- Archivo Municipal de Daroca, Libro de Estatutos - 1414 at bckg.pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

Literature

- Alfonso X of Castile (1273). El Libro de los Juegos. Toledo: Royal Scriptorium.

- Anon. (April 1833). "Article XXV: Lives of Scottish Worthies". The Monthly Review. London: Henderson. 1 (4): 609.

- Brand, John and William Carew Hazlitt (1870). Customs and Ceremonies. London: John Russell Smith.

- Carpenter, Andrew, ed. (1998). Verse in English from Eighteenth Century Ireland. Cork: Cork University Press. ISBN 1859181031.

- Casey, William (1851). The Anglo-Hispano Interpreter. Barcelona: Francis Oliva.

- Cotton, Charles (1674). The Compleat Gamester. London: A.M. OCLC 558875155. Modern reprint at the Internet Archive

- Dufief, N. G. (1825). La Naturaleza Descubierta. New York: Tompkins & Floyd.

- Willughby, Francis (2003). Forgeng, Jeff; Johnston, Dorothy; Cram, David (eds.). Francis Willughby's Book of Games. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 1-85928-460-4. (Critical edition of Willughby's volume containing descriptions of games and pastimes, c.1660-1672. Manuscript in the Middleton collection, University of Nottingham; document reference Mi LM 14)

- Howell, James (1635). Familiar Letters. Vol. 2.

- Johnson, Samuel (1818). "Aftergame". A Dictionary of the English Language. Vol. 1. London: Strahan. OCLC 50161172.

- Roger, Charles, ed. (1844). The Poems of Sir Robert Ayton. Edinburgh: Black. OCLC 557596756.

- Tytler, Patrick Fraser (1833). Lives of Scottish Worthies. Vol. 3. London: Murray. OCLC 500019983.