Douglas's Texas Battery

Douglas's Texas Battery (also known as the Good-Douglas Texas Battery or Dallas Light Artillery Battery) was an artillery battery that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. In June 1861, the unit was formed by combining one group of men from Dallas with a second group from Tyler and placing them under the command of John Jay Good. The battery fought at Pea Ridge in March 1862 and soon afterward transferred to the east side of the Mississippi River. James Postell Douglas replaced Good as commander and led the battery at Richmond, Stones River, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, the Atlanta Campaign, Franklin, and Nashville. After operations around Mobile, Alabama, Confederate units in the region surrendered and the survivors of the battery were paroled on 12 May 1865. It was the only Texas field artillery unit that served east of the Mississippi.

| Douglas's Texas Battery | |

|---|---|

Douglas's Texas Battery was armed with two M1841 6-pounder field guns (shown here) and two M1841 12-pounder howitzers in summer 1862. | |

| Active | 13 June 1861–12 May 1865 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Field Artillery |

| Size | Artillery Battery |

| Equipment | 2 M1841 12-pounder howitzers and 2 M1841 6-pounder field guns (Aug 1862) 4 12-pounder Napoleons (July 1864) |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | John Jay Good James Postell Douglas |

Formation

On 12 March 1859, John Jay Good formed 35 Dallas residents into the Dallas Light Artillery Battery, a unit belonging to the Texas militia. The battery's purpose may have been mainly social because its membership included some of the leading members of Dallas society. On 20 April 1861, Good accepted a captain's commission from Governor Edward Clark and was ordered to report to San Antonio. When he returned to Dallas, Good found that the Confederate States of America authorized him to raise a battery of artillery, which he began recruiting. He was ordered to join his Dallas company with a second 50-man militia artillery company from Tyler led by James Postell Douglas. The battery was intended to be armed with six guns including two howitzers.[1]

On 10 June 1861, Douglas's company left Tyler for Dallas carrying a flag made by the citizens of the town. When the full 100-man unit finally rendezvoused in Dallas on 13 June, the officers were named: Captain Good, First Lieutenant Douglas, and Second Lieutenants Alfred Davis, James Boren, and William Harriss. The average age of the soldiers was 26. Good's battery was subordinated to Colonel Elkanah Greer who led the 3rd Texas Cavalry Regiment. The soldiers then had to wait a few weeks for their military supplies to arrive. In mid-July three freight wagons arrived from San Antonio carrying four M1841 6-pounder field guns and other vital equipment.[2]

History

Good's Texas Battery

As Greer's cavalrymen and Good's artillerists left Dallas, they heard news that hostilities had begun in Missouri. In a letter sent home, Douglas believed that the war would be over by 1 November. While crossing the Red River, the waters unexpectedly rose, but the gunners were able to save their equipment. On 1 August 1861, the troops reached Fort Smith, Arkansas they were welcomed by the local residents. Benjamin McCulloch soon ordered the 3rd Texas Cavalry to continue its march and it participated in the Battle of Wilson's Creek in 13 August. However, Greer's rapid march through Indian Territory had damaged the equipment of Good's Battery to such an extent that it was compelled to halt at Fort Smith and effect repairs. The soldiers underwent training and drill during their stay at Fort Smith. The battery's first fatality occurred at Fort Smith on 15 August when an enlisted man died.[3]

Good's Battery joined McCulloch's troops near Bentonville, Arkansas during the winter months. In January 1862, a second enlisted man died of pneumonia.[4] Good's Battery fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge on 7–8 March as part of a division led by McCulloch. According to one source, Good's Battery was armed with four 12-pounder field guns and two M1841 12-pounder howitzers.[5] Confederate General Earl Van Dorn mounted a two pronged envelopment of the Federal army, sending McCulloch's division against Leetown from the northwest and Sterling Price's division against Elkhorn Tavern from the north. On 7 March, Price's division made some progress, but the Leetown attack failed; McCulloch and another general were killed and a third leader captured.[6] At about 4:00 pm, Albert Pike assumed command of McCulloch's division and marched to join Price with 2,000 troops and Good's Battery. Greer followed two hours later with the remaining 3,500 soldiers.[7]

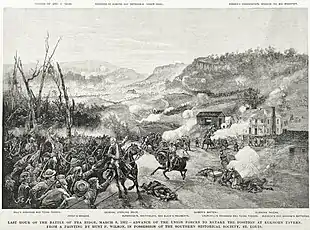

The morning of 8 March revealed 21 Federal cannons under Franz Sigel in a position overlooking the Confederate right flank near Elkhorn Tavern. Belatedly, Van Dorn ordered Good's six guns and the six guns of Wade's Missouri Battery to reply to the Union cannons. The Confederate gunners killed only four Union soldiers because they fired too high. However, the fire of the Federal guns was devastating. Good later wrote his wife, "It is a perfect miracle that any of us ever came out". Douglas estimated that at least 100 projectiles passed within twenty feet of him. When Good's Battery exhausted its ammunition, the men limbered up the guns and withdrew, leaving the flag behind in their haste.[8] Good's Battery sustained losses of one killed, 14 wounded, and two missing in the battle.[5] Good's Battery retreated from Pea Ridge by marching north and east. It and other wandering artillery units were discovered by the 3rd Texas Cavalry and 1st Missouri Cavalry on 10 March and escorted back to the main army. The Confederate army's logistics broke down during the retreat, so the troops stole food from farms that they passed. Since Price's Missourians led the retreat, McCulloch's men found very little to eat until the army crossed the Boston Mountains into central Arkansas.[9]

The Texans were irritated by Van Dorn's favoritism toward Price's Missourians. Good became furious when he read Van Dorn's official battle report. He wrote, "I did think myself in that fight until seeing the report but am now 'officially' satisfied it is a mistake. The chivalry of Texas was not upon the battle field of Elkhorn nor was my company. None of us like this. Texas plays second fiddle to Missouri."[10] On 25 March, Van Dorn received orders to cross to the east side of the Mississippi River.[11] By 27 April, Good's Battery arrived at Corinth, Mississippi where it was assigned to Joseph L. Hogg's brigade. [12] The battery would be the only Texas artillery unit to serve east of the Mississippi during the war.[13] Corinth proved to be an unhealthy campsite and many soldiers suffered from dysentery and typhoid fever. Good fell ill and resigned his command on 10 May 1862, the same day that the battery reorganized; he later served as a military judge.[14]

Douglas takes command

The battery's soldiers re-enlisted for two more years and elected new officers: Captain Douglas, First Lieutenant Boren, Second Lieutenant John Bingham, and Third Lieutenant Ben Hardin. From this time forward, the unit was called Douglas's Texas Battery and its size was reduced from six guns to four guns: two 6-pounder field guns and two 12-pounder howitzers.[14] The battery was assigned to Patrick Cleburne's division during Edmund Kirby Smith's invasion of Kentucky. When Douglas allowed his tired cannoneers to ride on the caissons and gun carriages, he was placed under arrest by Preston Smith, his brigade commander. Not wanting the soldiers to go into battle without their captain, Kirby Smith ordered Douglas's release. In the Battle of Richmond at the end of August, Cleburne ordered Douglas's Battery to take a position in the center of his battle line. For two hours there was a duel with 12 Union cannons, during which Boren commanded the two howitzers and Bingham directed the two 6-pounders.[15] Douglas's Battery was soon joined by Martin's Battery. In the lopsided victory that followed, the Confederates sustained losses of 78 killed, 372 wounded, and one missing while the Federals lost 206 killed, 844 wounded, plus 4,303 men and nine guns captured.[16]

At the Battle of Stones River on 31 December 1862–2 January 1863, Douglas's Battery served with Mathew D. Ector's brigade in John P. McCown's division of William J. Hardee's corps.[17] At the start of the Confederate attack on the first day, Douglas's Battery was positioned on the left flank of McCown's division. As the assault pressed forward, Douglas rode ahead, looking for a good position to support the infantry. He noticed a group of Union soldiers about 150 yd (137 m) distant who failed to identify his battery as an enemy unit. He ordered the guns unlimbered and opened fire with canister shot, causing the Federals to flee. While a number of horses were killed, the gun crews sustained few casualties in the battle.[18]

Douglas's Battery next fought in the Battle of Chickamauga on 19–20 September 1863 as part of the artillery battalion belonging to Cleburne's division of Daniel Harvey Hill's corps.[19] The unit was committed to the battle as darkness fell at 6:00 pm on the first day[20] near the Winfrey Field. Major T. R. Hotchkiss, Cleburne's chief of artillery, deployed all his batteries behind S. A. M. Wood's brigade in the center of Cleburne's line.[21] On the second day, the battery was unable to support James Deshler's Texas brigade.[22] In fact, Douglas's Battery had difficulty moving through the dense forest. When the unit finally reached a clearing, it was targeted by two Federal batteries, so Douglas ordered it back behind a hill.[20] At the end of the day, Semple's Alabama Battery, Calvert's Arkansas Battery, and Douglas's Texas Battery supported the final Confederate assault.[23]

At the Battle of Missionary Ridge on 25 November 1863, Douglas's Battery remained part of Cleburne's division.[24] That morning, James Argyle Smith's Texas brigade took position at the northern end of the ridge. When Smith was badly wounded early in the fighting, Hiram B. Granbury assumed command of the brigade. As the Texans came under attack, Cleburne posted Douglas's Battery near Granbury's right flank so that it would enfilade the Union attackers.[25] Though they repulsed the Federal troops opposed to them, the rest of the army was beaten and they were compelled to retreat.[26] On 18 January 1864, every man of Douglas's Texas Battery re-enlisted for a term of 25 years or the duration of the war. This act encouraged other Army of Tennessee units to re-enlist for the duration.[26] Douglas's Battery was the first Confederate unit to re-enlist.[13] On 16 February the Confederate States Congress passed a vote of thanks to the Texas Battery for its re-enlistment.[27]

Atlanta through Mobile

The Atlanta Campaign began in May 1864 in a year which would see Douglas's Battery fight in 16 battles or skirmishes. During the campaign, the battery fought at Resaca, Peachtree Creek, and Ezra Church.[26] The battery was assigned to Major A. R. Courtney's artillery battalion in John Bell Hood's corps. When Hood became the army commander, Stephen D. Lee assumed command of the corps.[28] During the Battle of Atlanta on 22 July, Douglas's Battery was sent into action at 4:00 pm with Thomas C. Hindman's division. The cannoneers found it difficult to inflict damage on their enemies because the Union soldiers fought from entrenchments. However, the battery acquired four 12-pounder Napoleon cannons that were captured from the Federal army. Lieutenant Bingham noted that while the battery's original guns were worn out, the Napoleons were new guns. Douglas wrote, "I have much the finest battery I have ever had and perhaps the finest in our army".[29]

Douglas's Battery fought in the Battle of Franklin on 30 November 1864. Douglas wrote, "I have seen many battles, but this one ... was the bloodiest I have seen". The battery lost one man killed and about 10 wounded during the struggle. This was followed by the Battle of Nashville on 15–16 December.[29] In the Nashville campaign, Douglas commanded the artillery battalion while the Texas Battery was led by Lieutenant Hardin. The battalion reported to Edward Johnson who commanded a division in S. D. Lee's corps.[30] On 17 December while serving as rearguard for the retreating army, all the battery's guns were captured.[29] That evening, Carter L. Stevenson led the rearguard with 700 infantry supported by Abraham Buford's cavalry. Edward Hatch's Union cavalry first scattered Buford's horsemen and, aided by darkness, managed to get among Stevenson's infantry in a confused melee. When Joseph F. Knipe's Union cavalry appeared, the Confederates took to their heels and Douglas's men abandoned three 12-pounder Napoleons.[31] Another account asserted that the guns became stuck in the mud. Douglas mounted a horse behind his younger brother and the two managed to get away.[27]

The battery was sent to defend Mobile, Alabama where they manned the siege guns of Fort Sidney Johnston.[29] Dabney H. Maury and 10,000 Confederate soldiers with 300 guns defended Mobile against 45,000 Federal troops under Edward Canby in March and April 1865. After the Battle of Fort Blakeley, Maury evacuated the city with his remaining 4,500 soldiers and 27 guns. On 4 May, Richard Taylor surrendered the Confederate soldiers in the region.[32] The survivors of Douglas's Texas Battery reported to Gainesville, Alabama where they gave their paroles on 12 May 1865 and went home. Douglas was returning from furlough at the time; when he heard the news, he went back to Texas.[33]

Notes

- Lang 2007, p. 26.

- Lang 2007, pp. 27–28.

- Lang 2007, pp. 28–29.

- Lang 2007, pp. 29–30.

- Shea & Hess 1992, p. 336.

- Boatner 1959, pp. 627–628.

- Shea & Hess 1992, p. 144.

- Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 230–233.

- Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 264–265.

- Shea & Hess 1992, p. 285.

- Shea & Hess 1992, p. 288.

- Lang 2007, p. 31.

- Lang 2007, p. 38.

- Lang 2007, pp. 31–32.

- Lang 2007, p. 33.

- Battles & Leaders 1987a, pp. 4–5.

- Battles & Leaders 1987a, p. 612.

- Lang 2007, p. 34.

- Battles & Leaders 1987a, p. 674.

- Lang 2007, p. 35.

- Cozzens 1996, pp. 266–267.

- Cozzens 1996, p. 349.

- Cozzens 1996, p. 496.

- Cozzens 1994, p. 412.

- Cozzens 1994, pp. 212–215.

- Lang 2007, p. 36.

- Cutrer 2010.

- Battles & Leaders 1987b, p. 291.

- Lang 2007, p. 37.

- Battles & Leaders 1987b, p. 473.

- Sword 1992, pp. 398–399.

- Boatner 1959, p. 559.

- Lang 2007, pp. 37–38.

References

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 3. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987a [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-571-X.

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 4. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987b [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-572-8.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Cozzens, Peter (1994). The Shipwreck of their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01922-9.

- Cozzens, Peter (1996). This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06594-8.

- Cutrer, Thomas W.: James Postell Douglas from the Handbook of Texas Online (June 12, 2010). Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- Lang, Andrew F. (2007). "Lone Star Pride: The Good-Douglas Texas Battery, CSA 1861–1865". East Texas Historical Journal. 45 (2): 26–40.

- Shea, William L.; Hess, Earl J. (1992). Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4669-4.

- Sword, Wiley (1992). The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. New York, N.Y.: University Press of Kansas for HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7006-0650-5.