The Dream of Gerontius

The Dream of Gerontius, Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment before God and settling into Purgatory. Elgar disapproved of the use of the term "oratorio" for the work (and the term occurs nowhere in the score), though his wishes are not always followed. The piece is widely regarded as Elgar's finest choral work, and some consider it his masterpiece.

The work was composed for the Birmingham Music Festival of 1900; the first performance took place on 3 October 1900, in Birmingham Town Hall. It was badly performed at the premiere, but later performances in Germany revealed its stature. In the first decade after its premiere, the Roman Catholic theology in Newman's poem caused difficulties in getting the work performed in Anglican cathedrals, and a revised text was used for performances at the Three Choirs Festival until 1910.

History

Edward Elgar was not the first composer to think about setting John Henry Newman's poem "The Dream of Gerontius". Dvořák had considered it fifteen years earlier, and had discussions with Newman, before abandoning the idea.[1] Elgar knew the poem well; he had owned a copy since at least 1885, and in 1889 he was given another as a wedding present. This copy contained handwritten transcriptions of extensive notes that had been made by General Gordon, and Elgar is known to have thought of the text in musical terms for several years.[2] Throughout the 1890s, Elgar had composed several large-scale works for the regular festivals that were a key part of Britain's musical life. In 1898, based on his growing reputation, he was asked to write a major work for the 1900 Birmingham Triennial Music Festival.[3] He was unable to start work on the poem that he knew so well until the autumn of 1899, and did so only after first considering a different subject.[4]

Composition proceeded quickly. Elgar and August Jaeger, his editor at the publisher Novello, exchanged frequent, sometimes daily, letters,[5] which show how Jaeger helped in shaping the work, and in particular the climactic depiction of the moment of judgment.[6] By the time Elgar had completed the work and Novello had printed it, there were only three months to the premiere. The Birmingham chorus, all amateurs, struggled to master Elgar's complex, demanding and somewhat revolutionary work. Matters were made worse by the sudden death of the chorus master Charles Swinnerton Heap and his replacement by William Stockley, an elderly musician who found the music beyond him.[7] The conductor of the premiere, Hans Richter, received a copy of the full score only on the eve of the first orchestral rehearsal.[8] The soloists at the Birmingham Festival on 3 October 1900 were Marie Brema, Edward Lloyd and Harry Plunket Greene.[9] The first performance was, famously, a near disaster. The choir could not sing the music adequately, and two of the three soloists were in poor voice.[10] Elgar was deeply upset at the debacle, telling Jaeger, "I have allowed my heart to open once – it is now shut against every religious feeling & every soft, gentle impulse for ever."[11] However, many of the critics could see past the imperfect realisation and the work became established in Britain[12][13] once it had had its first London performance on 6 June 1903, at the Roman Catholic Westminster Cathedral.[14][15]

Shortly after the premiere, the German conductor and chorus master Julius Buths made a German translation of the text and arranged a successful performance in Düsseldorf on 19 December 1901. Elgar was present, and he wrote "It completely bore out my idea of the work: the chorus was very fine".[16] Buths presented it in Düsseldorf again on 19 May 1902 in conjunction with the Lower Rhenish Music Festival.[17] The soloists included Muriel Foster[18] and tenor Ludwig Wüllner,[19] and Elgar was again in the audience, being called to the stage twenty times to receive the audience's applause.[18] This was the performance that finally convinced Elgar for the first time that he had written a truly satisfying work.[20] Buths's festival co-director Richard Strauss was impressed enough by what he heard that at a post-concert banquet he said: "I drink to the success and welfare of the first English progressive musician, Meister Elgar".[17] This greatly pleased Elgar,[18] who considered Strauss to be "the greatest genius of the age".[21]

The strong Roman Catholicism of the work gave rise to objections in some influential British quarters; some Anglican clerics insisted that for performances in English cathedrals Elgar should modify the text to tone down the Roman Catholic references. There was no Anglican objection to Newman's words in general: Arthur Sullivan's setting of his "Lead, Kindly Light", for example, was sung at Westminster Abbey in 1904.[22] Disapproval was reserved for the doctrinal aspects of The Dream of Gerontius repugnant to Anglicans, such as Purgatory.[23] Elgar was unable to resist the suggested bowdlerisation, and in the ten years after the premiere the work was given at the Three Choirs Festival with an expurgated text.[24] The Dean of Gloucester refused admission to the work until 1910.[25][26] This attitude lingered until the 1930s, when the Dean of Peterborough banned the work from the cathedral.[27] Elgar was also faced with many people's assumption that he would use the standard hymn tunes for the sections of the poem that had already been absorbed into Anglican hymn books: "Firmly I believe and truly", and "Praise to the Holiest in the Height".[22]

The Dream of Gerontius received its US premiere on 23 March 1903 at The Auditorium, Chicago, conducted by Harrison M. Wild. It was given in New York, conducted by Walter Damrosch three days later.[28] It was performed in Sydney, in 1903.[28] The first performance in Vienna was in 1905;[29] the Paris premiere was in 1906;[30] and by 1911 the work received its Canadian premiere in Toronto under the baton of the composer.

In the first decades after its composition leading performers of the tenor part included Gervase Elwes and John Coates, and Louise Kirkby Lunn, Elena Gerhardt and Julia Culp were admired as the Angel. Later singers associated with the work include Muriel Foster, Clara Butt, Kathleen Ferrier, and Janet Baker as the Angel, and Heddle Nash, Steuart Wilson, Tudor Davies and Richard Lewis as Gerontius.[11]

The work has come to be generally regarded as Elgar's finest choral composition. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians rates it as "one of his three or four finest works", and the authors of The Record Guide, writing in 1956 when Elgar's music was comparatively neglected, said, "Anyone who doubts the fact of Elgar's genius should take the first opportunity of hearing The Dream of Gerontius, which remains his masterpiece, as it is his largest and perhaps most deeply felt work."[31] In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Michael Kennedy writes, "[T]he work has become as popular with British choral societies as Messiah and Elijah, although its popularity overseas did not survive 1914. Many regard it as Elgar's masterpiece. ... It is unquestionably the greatest British work in the oratorio form, although Elgar was right in believing that it could not accurately be classified as oratorio or cantata."[14]

Synopsis

Newman's poem tells the story of a soul's journey through death, and provides a meditation on the unseen world of Roman Catholic theology. Gerontius (a name derived from the Greek word geron, "old man") is a devout Everyman.[12][32] Elgar's setting uses most of the text of the first part of the poem, which takes place on Earth, but omits many of the more meditative sections of the much longer, otherworldly second part, tightening the narrative flow.[4]

In the first part, we hear Gerontius as a dying man of faith, by turns fearful and hopeful, but always confident. A group of friends (also called "assistants" in the text) joins him in prayer and meditation. He passes in peace, and a priest, with the assistants, sends him on his way with a valediction. In the second part, Gerontius, now referred to as "The Soul", awakes in a place apparently without space or time, and becomes aware of the presence of his guardian angel, who expresses joy at the culmination of his task (Newman conceived the Angel as male; Elgar gives the part to a female singer, but retains the references to the angel as male). After a long dialogue, they journey towards the judgment throne.

They safely pass a group of demons, and encounter choirs of angels, eternally praising God for His grace and forgiveness. The Angel of the Agony pleads with Jesus to spare the souls of the faithful. Finally Gerontius glimpses God and is judged in a single moment. The Guardian Angel lowers Gerontius into the soothing lake of Purgatory, with a final benediction and promise of a re-awakening to glory.

Music

Forces

The work calls for a large orchestra of typical late Romantic proportions, double chorus with semichorus, and usually three soloists. Gerontius is sung by a tenor, and the Angel is a mezzo-soprano. The Priest's part is written for a baritone, while the Angel of the Agony is more suited to a bass; as both parts are short they are usually sung by the same performer, although some performances assign different singers for the two parts.

The choir plays several roles: attendants and friends, demons, Angelicals (women only) and Angels, and souls in Purgatory. They are employed at different times as a single chorus in four parts, or as a double chorus in eight parts or antiphonally. The semichorus is used for music of a lighter texture; usually in performance they are composed of a few members of the main chorus; however, Elgar himself preferred to have the semi-chorus placed near the front of the stage.

The required instrumentation comprises two flutes (II doubling piccolo), two oboes and cor anglais, two clarinets in B♭ and A and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani plus three percussion parts, harp, organ, and strings. Elgar called for an additional harp if possible, plus three additional trumpets (and any available percussionists) to reinforce the climax in Part II, just before Gerontius's vision of God.

Form

Each of the two parts is divided into distinct sections, but differs from the traditional oratorio in that the music continues without significant breaks. Elgar did not call the work an oratorio, and disapproved when other people used the term for it.[33] Part I is approximately 35 minutes long and Part II is approximately 60 minutes.

Part I:

- Prelude

- Jesu, Maria – I am near to death

- Rouse thee, my fainting soul

- Sanctus fortis, sanctus Deus

- Proficiscere, anima Christiana

Part II:

- I went to sleep

- It is a member of that family

- But hark! upon my sense comes a fierce hubbub

- I see not those false spirits

- But hark! a grand mysterious harmony

- Thy judgment now is near

- I go before my judge

- Softly and gently, dearly-ransomed soul

Part I

The work begins with an orchestral prelude, which presents the most important motifs. In a detailed analysis, Elgar's friend and editor August Jaeger identified and named these themes, in line with their functions in the work.[34]

Gerontius sings a prayer, knowing that life is leaving him and giving voice to his fear, and asks for his friends to pray with him. For much of the soloist's music, Elgar writes in a style that switches between exactly notated, fully accompanied recitative, and arioso phrases, lightly accompanied. The chorus adds devotional texts in four-part fugal writing. Gerontius's next utterance is a full-blown aria Sanctus fortis, a long credo that eventually returns to expressions of pain and fear. Again, in a mixture of conventional chorus and recitative, the friends intercede for him. Gerontius, at peace, submits, and the priest recites the blessing "Go forth upon thy journey, Christian soul!" (a translation of the litany Ordo Commendationis Animae). This leads to a long chorus for the combined forces, ending Part I.[35]

Part II

In a complete change of mood, Part II begins with a simple four-note phrase for the violas which introduces a gentle, rocking theme for the strings. This section is in triple time, as is much of the second part. The Soul's music expresses wonder at its new surroundings, and when the Angel is heard, he expresses quiet exultation at the climax of his task. They converse in an extended duet, again combining recitative with pure sung sections. Increasingly busy music heralds the appearance of the demons: fallen angels who express intense disdain of men, mere mortals by whom they were supplanted. Initially the men of the chorus sing short phrases in close harmony, but as their rage grows more intense the music shifts to a busy fugue, punctuated by shouts of derisive laughter.[35]

Gerontius cannot see the demons, and asks if he will soon see his God. In a barely accompanied recitative that recalls the very opening of the work, the Angel warns him that the experience will be almost unbearable, and in veiled terms describes the stigmata of St. Francis. Angels can be heard, offering praises over and over again. The intensity gradually grows, and eventually the full chorus gives voice to a setting of the section that begins with Praise to the Holiest in the Height. After a brief orchestral passage, the Soul hears echoes from the friends he left behind on earth, still praying for him. He encounters the Angel of the Agony, whose intercession is set as an impassioned aria for bass. The Soul's Angel, knowing the long-awaited moment has come, sings an Alleluia.[35]

The Soul now goes before God and, in a huge orchestral outburst, is judged in an instant. At this point in the score, Elgar instructs "for one moment, must every instrument exert its fullest force." This was not originally in Elgar's design, but was inserted at the insistence of Jaeger, and remains as a testament to the positive musical influence of his critical friendship with Elgar. In an anguished aria, the Soul then pleads to be taken away. A chorus of souls sings the first lines of Psalm 90 ("Lord, thou hast been our refuge") and, at last, Gerontius joins them in Purgatory. The final section combines the Angel, chorus, and semichorus in a prolonged song of farewell, and the work ends with overlapping Amens.[35]

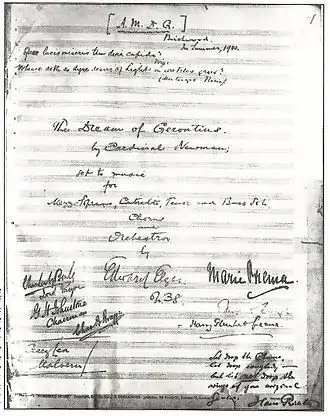

Dedication and superscription

Elgar dedicated his work "A.M.D.G." (Ad maiorem Dei gloriam, "To the greater glory of God", the motto of the Society of Jesus or Jesuits), following the practice of Johann Sebastian Bach, who would dedicate his works "S.D.G." (Soli Deo gloria, "Glory to God alone").[36] Underneath this he wrote a line from Virgil: "Quae lucis miseris tam dira cupido?" together with Florio's English translation of Montaigne's adaptation of Virgil's line: "Whence so dyre desire of Light on wretches grow?"[36]

At the end of the manuscript score, Elgar wrote this quotation from John Ruskin's Sesame and Lilies:

- This is the best of me; for the rest, I ate, and drank, and slept, loved and hated, like another: my life was as the vapour and is not; but this I saw and knew; this, if anything of mine, is worth your memory.[12]

Richter signed the autograph copy of the score with the inscription: "Let drop the Chorus, let drop everybody—but let not drop the wings of your original genius."[8]

Recordings

Henry Wood made acoustic recordings of four extracts from The Dream of Gerontius as early as 1916, with Clara Butt as the Angel.[11] Edison Bell issued the work in 1924 with Elgar's tacit approval (despite his contract with HMV); acoustically recorded and abridged, it was swiftly rendered obsolete by the introduction of the electrical process, and soon after withdrawn. HMV issued live recorded excerpts from two public performances conducted by Elgar in 1927, with the soloists Margaret Balfour, Steuart Wilson, Tudor Davies, Herbert Heyner, and Horace Stevens.[37] Private recordings from radio broadcasts ("off-air" recordings) also exist in fragmentary form from the 1930s.

The first complete recording was made by EMI in 1945, conducted by Malcolm Sargent with his regular chorus and orchestra, the Huddersfield Choral Society and the Liverpool Philharmonic. The soloists were Heddle Nash, Gladys Ripley, Dennis Noble and Norman Walker. This is the only recording to date that employs different singers for the Priest and the Angel of the Agony.[11] The first stereophonic recording was made by EMI in 1964, conducted by Sir John Barbirolli. It has remained in the catalogues continuously since its first release, and is notable for Janet Baker's singing as the Angel.[11] Benjamin Britten's 1971 recording for Decca was noted for its fidelity to Elgar's score, showing, as the Gramophone reviewer said, that "following the composer's instructions strengthens the music's dramatic impact".[11] Of the other dozen or so recordings on disc, most are directed by British conductors, with the exception of a 1960 recording in German under Hans Swarowsky and a Russian recording (sung in English by British forces) under Yevgeny Svetlanov performed 'live' in Moscow in 1983.[38] Another Russian conductor, Vladimir Ashkenazy, performed the work with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and its choral and vocal soloists in 2008 and this too has been released on CD.

The BBC Radio 3 feature "Building a Library" has presented comparative reviews of all available versions of The Dream of Gerontius on three occasions. Comparative reviews also appear in The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music, 2008, and Gramophone, February 2003. The recordings recommended by all three are Sargent's 1945 EMI version and Barbirolli's 1964 EMI recording.[11][39][40]

Arrangements

Prelude to The Dream of Gerontius, arranged by John Morrison for symphonic wind band, publisher Molenaar Edition.

Taking his cue from Wagner's Prelude and Liebestod, Elgar himself made an arrangement entitled Prelude and Angel's Farewell subtitled "for orchestra alone" which was published in 1902 by Novello. In 1917 he recorded a drastically abridged version of this transcription on a single-sided acoustic 78rpm disc.

In popular culture

The work features as a key plot point in the 1974 BBC Play for Today by David Rudkin, Penda's Fen.[41]

See also

Notes

- Moore, p. 291

- Moore, p. 290

- Moore, p. 256

- Moore, p. 296

- Moore, pp. 302–316

- Moore, p. 322

- Moore, p. 325

- The Musical Times, 1 November 1900, p. 734

- Moore, p. 331

- Reed 1946, p. 60.

- Farach Colton, Andrew, "Vision of the Hereafter", Gramophone, February 2003, p. 36

- McVeagh, Diana. "Elgar, Sir Edward." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed 21 October 2010. (subscription required)

- Moore, p. 357

- Kennedy, Michael, "Elgar, Sir Edward William, baronet (1857–1934)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 22 April 2010 (subscription required).

- 'The Dream of Gerontius', in The Daily Telegraph, 8 June 1903. p.7

- Moore, p. 362

- Reed 1946, p. 61

- Moore, p. 368

- Foreman, Lewis. "Max von Schillings (1868–1933) / String Quartet in E minor". Music Web International. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Elgar's Blessed Charmer – Muriel Foster". Music Web International. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- Liner notes to Salome, Decca Records, 2006, OCLC 70277106

- The Times, 13 February 1904, p. 13

- "A Dean's Objections to The Dream of Gerontius", The Manchester Guardian, 17 November 1903. p. 12

- The Times, 11 September 1903 and 13 September 1905

- McGuire, Charles Edward, "Measure of a Man", in Edward Elgar and his World, ed. Byron Adams, Princeton University Press, 2007, p. 6

- Lewis, Geraint, "A Cathedral in Sound", Gramophone, September 2008, p. 50. The Gloucester performance in 1910 was described in The Manchester Guardian (5 September 1910, p. 7) as "given unmutilated for the first time in an Anglican cathedral".

- "Cathedral Ban on 'Gerontius'," The Manchester Guardian, 19 October 1932, p. 9

- Hodgkins 1999, p. p=187

- McColl, Sandra, "Gerontius in the City of Dreams: Newman, Elgar, and the Viennese Critics", International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, vol. 32, no. 1 (June 2001), pp. 47–64

- The Musical Times, April 1934, p. 318

- Sackville-West & Shawe-Taylor 1955, p. 254.

- The name "Gerontius" is not sung in the work, and there is no consensus on how it is pronounced. The Greek "geron" has a hard 'g'; but English words derived from it often have a soft 'g', as in "geriatriac"

- "Dream of Gerontius, The", Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford Music Online, accessed 22 October 2010 (subscription required)

- Jaeger's analysis is summarised at Burton, James "The Dream of Gerontius, British Choirs on the Net, accessed 22 October 2010

- Grove; Jenkins, Lyndon (1987), notes to EMI CD CMS 7 63185 2; and Moore, Jerrold Northrop (1975), notes to Testament CD SBT 2025

- Moore, p. 317

- "The Elgar Birthday Records", The Gramophone, June 1927, p. 17

- Essex, Walter, "The Recorded Legacy", The Elgar Society, accessed 22 October 2010

- Building a Library BBC Radio 3; Building a Library, BBC Radio 3

- March 2007, pp. 438–440.

- Graham Fuller (5 June 2017). "In quest of the Romantic tradition in British film: Penda's Fen". BFI. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

Sources

- Hodgkins, Geoffrey (1999). The Best of Me – A Gerontius Centenary Companion. Rickmansworth: Elgar Editions. ISBN 0-9537082-0-9.

- March, Ivan, ed. (2007). The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-103336-5.

- Moore, Jerrold Northrop (1984). Edward Elgar: A Creative Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315447-1.

- Reed, W. H. (1946). Elgar. London: Dent. OCLC 8858707.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Shawe-Taylor, Desmond (1955). The Record Guide. Collins. OCLC 474839729.

Further reading

- The Best of Me – A Gerontius Companion

- Adams, Byron (2004). "Elgar's later oratorios: Roman Catholicism, Decadence and the Wagnerian Dialectic of Shame and Grace". In Grimley, Daniel M.; Rushton, Julian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Elgar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–105. ISBN 0-521-53363-5.

- Begbie, Jeremy S. (2012). "Confidence and Anxiety in Elgar's Dream of Gerontius". In Clarke, Martin V. (ed.). Music and Theology in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. pp. 197–213. ISBN 978-1-4094-0989-2.

- Csizmadia, Florian (2017). Leitmotivik und verwandte Techniken in den Chorwerken von Edward Elgar. Analysen und Kontexte. Berlin: Verlag Dr. Köster. ISBN 978-3-89574-903-2.

- Kennedy, Michael (1982). Portrait of Elgar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315414-5.

- McGuire, Charles Edward (2002). Elgar's Oratorios: The Creation of an Epic Narrative. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-0271-0.

External links

- The Elgar Birthplace Museum

- The Dream of Gerontius on CD

- The Dream of Gerontius: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- The full text of the poem (Note: Elgar used about half the poem in his libretto.)

- Elgar – His Music : The Dream of Gerontius – the libretto

- Elgar – His Music : The Dream of Gerontius – A Musical Analysis – first of a set of six pages on the work

- A comparative review of the available recordings, at least up to 1997

- The Dream of Gerontius (1899–1900), analysis and synopsis, BBC