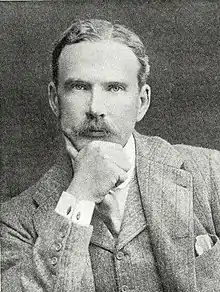

Harry Plunket Greene

Harry Plunket Greene (24 June 1865 – 19 August 1936) was an Irish baritone who was most famous in the formal concert and oratorio repertoire. He wrote and lectured on his art, and was active in the field of musical competitions and examinations. He also wrote Where the Bright Waters Meet (1924) a book about fly fishing.

Early life and training

Plunket Greene was born in Dublin, the son of Richard Jonas Greene, a barrister, and Louisa Lilias Plunket, a children's writer, granddaughter of William Conyngham Plunket, Lord Chancellor of Ireland.[1] He was educated at Clifton College[2] and initially expected to follow Law at Oxford. However, after he was 'smashed up' in a football accident he had a year's convalescence.

Discovering his musical calling he studied under Arthur Barraclough in Dublin before attending the Stuttgart Conservatory for two years under Antonín Hromada in the early 1880s. He also studied in Florence with Luigi Vannuccini (a pupil of Francesco Lamperti), and in London with J. B. Welsh and Alfred Blume.[3]

Early career

He made his debut in London (at the People's Palace, Mile End) in 1888, in Handel's Messiah,[3] and in the next year appeared in Gounod's Redemption. In 1890 he made operatic debuts as Commendatore in Don Giovanni and as the Duke of Verona in Romeo et Juliette, at Covent Garden. Thereafter he elected to make his career in recital.

In oratorio, his first Festival appearance was at Worcester in 1890. Plunket Greene created the title part in Hubert Parry's Job, at the Gloucester Festival in 1892. This includes the Lamentation of Job, an extremely long (28-page) and sustained oratorio scena. David Bispham said of his performances that he 'created the part and rendered it many times with superb dramatic feeling.'[4] Plunket became the original exponent or dedicatee of many of the lyrical works of Parry,[3]

In 1891 Bernard Shaw found him "fairly equal to the occasion in the wonderful duet" from Bach's Whitsuntide Canatata, O, Ewiges Feuer, with the Bach Choir. In April 1892 (sharing the platform with Joseph Joachim and Franz Xaver Neruda, Fanny Davies, Alfredo Piatti and Agnes Zimmermann (piano)) he sang admirably in his first set (Jean-Baptiste Lully, Peter Cornelius and Robert Schumann) in a Monday Popular Concert, but made little of his second group. In November 1893 at the first of George Henschel's London Symphony Orchestra concerts for the season he performed Stanford's new song, "Prince Madoc's Farewell", so patriotically 'that he once or twice almost burst into the next key.' Shaw's strictures on his diction were no doubt taken very seriously by the singer, who studied to make absolute clarity and naturalness of diction a central point of his teaching and example.[5] His early accompanist Henry Bird gained an appointment as accompanist to the Chappell Ballad Concerts after his partnership with Plunket Greene in the Hungarian Songs of Francis Korbay.[6]

Recitals–partnership with Leonard Borwick

On 11 January 1895 at St James's Hall, Leonard Borwick and Greene gave the first complete public performance of Schumann's Dichterliebe to be heard in London. Their musical partnership was still active in 1913, but the demands of their separate tours became so great by the early 1900s that they agreed not to continue their former recital programme unless it could be done wholeheartedly. Plunket Greene toured especially in the United States, where he considered the audiences especially attentive and appreciative, and in Germany. He also liked northern English audiences better than southern ones, and liked singing to audiences of public schoolboys.[7]

Gerontius and after

Plunket Greene was a friend of Edward Elgar, and appeared in his Malvern Concert Club events.[8] He was the original baritone in the first (October 1900) performance (Birmingham Festival) of Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius, alongside Marie Brema (angel) and Edward Lloyd (soul), under Hans Richter. In June 1900 Elgar had written to August Jaeger, "he sings both bass bits and won't they suit him. Gosh."[9]

Plunket Greene included a selection from the Songs of Travel by Ralph Vaughan Williams in recital in February 1905. Then (or soon afterwards) the composer heard him and dedicated the songs to him, and Greene afterwards quoted from them, and from Silent Noon (from the House of Life cycle), in his work on Interpretation in Song. Greene was responsible for establishing these songs in the English concert repertoire, where he was constantly attempting to raise the standard and quality of appreciation of English songs through his programming.[10]

He supported Gervase Elwes from the start of the latter's professional career and was his lifelong friend. At Elwes' audition for the Royal College of Music in 1903 Greene wrote to encourage him with the favourable reactions of Parry and Stanford,[11] and soon afterwards put him up for the Savile Club in London.[12] In 1906, he joined the party at Brigg to sing in the second festival there organised by Elwes and Percy Grainger, and declared his wish to be in many more of them.[13] When Elwes died in 1921, Greene wrote "I always felt he was the man I most looked up to."[14] 'In the St Matthew Passion, (he) made us feel that he of all men was best fitted to tell us the greatest story in the world.'[15]

On 24 January 1910 he appeared in the memorial concert at Queen's Hall for August Jaeger (Elgar's 'Nimrod'), singing a group of songs by Walford Davies, and Hans Sachs's monologue from Die Meistersinger.[16] He made his first appearance in Henry Wood's Promenade Concerts at the Queen's Hall in October 1914 singing Stanford's Songs of the Sea with the Alexandra Palace Choral Society.[17] He had declined to fulfil an engagement to sing them there for the Stock Exchange Orchestral Society in 1907 on hearing that they still used the high English concert pitch.[18]

Competitions and festivals, teaching

In his later years, Plunket Greene was busily involved in the organisation of music events and in teaching and administration. In 1923 he made his fifteenth voyage across the Atlantic (the first had been in 1893), on this occasion to act as a judge in Musical Competitions throughout Canada. From New York, he went to Toronto by train to join Granville Bantock. This was to be at the five Festivals of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. This was the first Ontario Festival (Toronto) (with Robert Watkin-Mills and Boris Hambourg also in attendance), the 6th in Winnipeg (with Herbert Witherspoon and Cecil Forsyth assisting), where the Earl Grey trophy was competed for, the 16th in Edmonton (Alberta), with choirs from Lethbridge and Calgary, and in Prince Albert they were with Herbert Howells. The promotion and encouragement of these events provided not only a great spectacle and opportunity for music—making but also infused a competitive spirit into the works of choirs, singers and instrumentalists in the award of prizes (in the tradition begun at Kendal, UK in c.1889), tending to the encouragement of excellence. Plunket Greene repeated the experience in Saskatchewan in 1931, together with Harold Samuel, Maurice Jacobson and Hugh Roberton.[19]

Among his pupils were Keith Falkner, whom Plunket Greene coached in his interpretation of the Lamentation of Job in Parry's Job,[20] Robert Easton,[21] and Margaret Ritchie.[22]

Personal life

Plunkett Greene married Gwendolen Maud Parry, Parry's younger daughter, in 1899. The couple had three children: Richard Plunket Greene (born 1901), David Plunket Greene (born 1904) and Olivia Plunket Greene (born 1907). The marriage was an unhappy one, and they separated in 1920.

His grandson Alexander Plunkett Greene married the fashion designer Mary Quant in 1953.[23]

Plunket Greene died on 19 August 1936, aged 71. He was buried in the churchyard of Hurstbourne Priors, near the graves of his two sons.[24]

Publications

- Interpretation in Song (London: Macmillan, 1912)

- Pilot and other stories (London: Macmillan, 1916)

- Where the Bright Waters Meet (London: Philip Allan, 1924)

- From Blue Danube to Shannon (London: Philip Allan, 1935)

- Charles Villiers Stanford (London: Edward Arnold, 1935)

Recordings

Harry Plunket Greene recorded songs both for the Gramophone Company and Columbia Records.

Published recordings for the Gramophone Company (1904–08):

- 2-42776 Abschied (Schubert). 22 January 1904; matrix 4891b

- 3-2016 Off to Philadelphia (Battison Haynes). 22 January 1904; matrix 4892b

- 3-2017 a) Mary (Goodheart) b) Quick, we have but a second (Stanford). 22 January 1904; matrix 4894b

- 3-2018 Father O'Flynn (arr Stanford). 22 January 1904; matrix 4894b

- 3-2059 (a) Eva Toole (b) Trottin' to the fair (Stanford). 14 February 1904; matrix 5065b

- 3-2060 The Donovans (Needham). 14 February 1904; matrix 5067b

- 3-2089 Over here (Wood). 4 January 1904; matrix 4779b

- 3-2333 a) The happy farmer (Somervell) b) Black Sheila of the silver eye (Harty). 30 May 1905; matrix 2114e

- 3-2334 The gentle maiden. 30 May 1905; matrix 2116e

- 3-2335 Little red fox (arr. Somervell). 30 May 1905; matrix 2113e

- 3-2336 Little Mary Cassidy. 30 May 1905; matrix 2121e

- 3-2337 Johneen (Stanford). 30 May 1905; matrix 2120e

- 4-2017 Molly Brannigan (arr Stanford). 14 December 1908; matrix 9282e

- 02174 Off to Philadelphia (Battison Haynes). 14 December 1908; matrix 2741f (12")

Columbia (electric) recordings:

- DB 1321 Poor Old Horse (Trad). 13 November 1933; matrix CA14156-1

- DB 1321 The Garden Where The Praties Grow (Trad). 10 January 1934; matrix CA 14157-2

- DB 1377 Trottin' to the Fair (Stanford). 10 January 1934; matrix CA14158-3

- DB 1377 The Hurdy-Gurdy Man (Schubert). 10 January 1934; matrix CA14259-1 wav available [Dec 2009] from

In addition to recordings of songs, he also recorded a Lecture 'On The Art of Singing' for the Columbia Records International Educational Society series (Lecture 75), on four sides, Disc numbers D40149-40150.[25]

References

- "Harry Plunket Greene". Irish Heritage. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J.A.O. p70: Bristol; J.W Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April, 1948

- Eaglefield-Hull 1924.

- Bispham 1920, 159.

- Shaw 1932, i, 107, 129; ii, 73, 89; iii, 86–88.

- Harold Simpson, 'Ch. XI: Plunket Greene, and Stanford's Irish songs' in A Century of Ballads, 1810-1910 (Mills and Boon, London 1910), pp. 237-247.

- Plunket Greene 1934 (Blue Danube to Shannon), 74–89.

- Young 1956, 126–127.

- Young 1956, 84.

- Rufus Hallmark, 'Robert Louis Stevenson, Ralph Vaughan Williams and their Songs of Travel,' in Brian Adams and Robin Wells (Eds.), Vaughan Williams Essays Vol 44 (Ashgate Publishing, 2003), pp. 135, 138.

- Elwes 1935, 127.

- Elwes 1935, 155.

- Elwes 1935, 165.

- Elwes 1935, 281–282.

- Elwes 1935, 296–297.

- Elkin 1944, 41.

- Wood 1946, 295: Elkin 1944, 70.

- Elkin 1944, 104.

- From Blue Danube to Shannon, Chapters II and VII.

- Brook 1958, 76.

- "Chesterfield Items", Derbyshire Times, 24 December 1943, p. 5

- Shawe-Taylor, Desmond."Ritchie, Margaret", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002 (subscription required)

- "Mary Quant: 'You have to work at staying slim - but it's worth it' - Telegraph". fashion.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- "Biography". Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Catalogue of Columbia Records, September 1933 (Columbia Graphophone Company, London 1933), p. 374.

Sources

- D. Bispham: A Quaker Singer's Recollections (London: Macmillan, 1920)

- D. Brook: Singers of Today (London: Rockliff, 1958), 'Keith Falkner', pp 75–78.

- Arthur Eaglefield Hull: A Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians (London: Dent, 1924)

- R. Elkin: Queen's Hall 1893–1941 (London: Rider, 1944)

- W. Elwes and R. Elwes: Gervase Elwes, The Story of his Life (London: Grayson & Grayson, 1935)

- H. Plunket Greene: From Blue Danube to Shannon (London: Philip Allan, 1934)

- M. Scott: The Record of Singing to 1914 (London: Duckworth, 1977)

- G.B. Shaw: Music in London 1890–1894, 3 vols. (London: Constable & Co., 1932)

- H. Wood: My Life of Music (London: Gollancz, 1938)

- P.M. Young: Letters of Edward Elgar (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1956)

External links

- . . Dublin: Alexander Thom and Son Ltd. 1923. pp. – via Wikisource.