Drexel 4180–4185

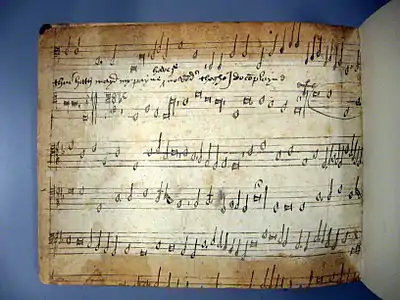

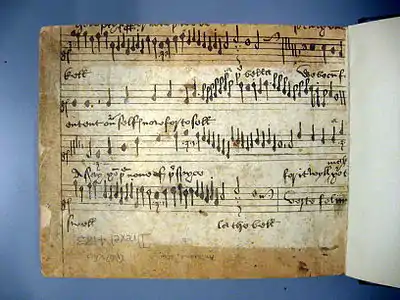

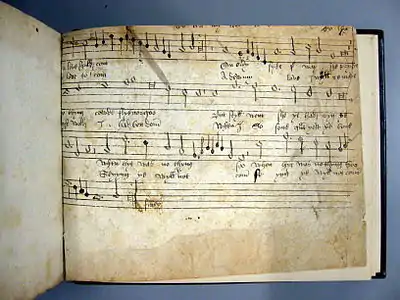

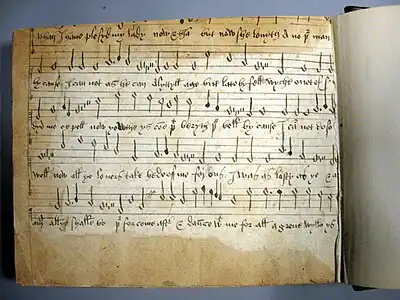

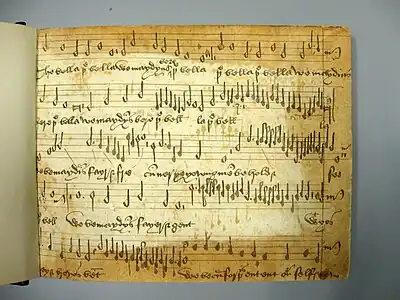

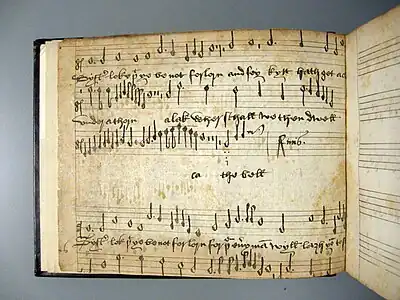

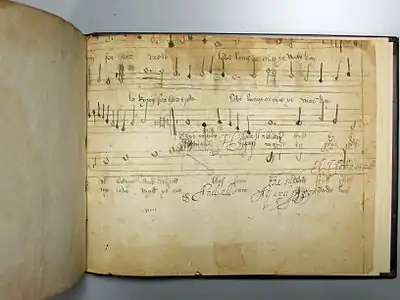

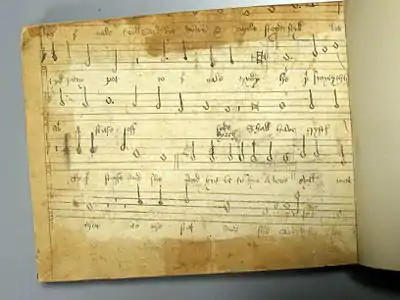

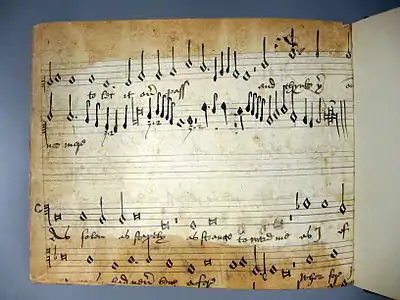

Drexel 4180–4185 is a set of six manuscript partbooks copied in Gloucester, England, containing primarily vocal music dating from approximately 1615-1625. Considered one of the most important sources for seventeenth century English secular song,[1] the repertoire included represents a mixture of sacred and secular music, attesting to the partbooks' use for entertainment and pleasure, rather than exclusively for liturgical use.

| Drexel 4180–4185 | |

|---|---|

| New York Public Library for the Performing Arts | |

Drexel 4180–4185, a set of six manuscript partbooks | |

| Date | 1615-1625 |

| Place of origin | England |

| Language(s) | English |

| Scribe(s) | John Merro |

| Author(s) | various |

| Size | 6 partbooks |

| Format | oblong |

When rebound in 1950, it was discovered that the pastedown endpapers from the original bindings had been created from 16th century English music manuscripts. These fragments have become an additional source of study.

Belonging to the New York Public Library, the partbooks are part of the Music Division's Drexel Collection, located at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Following traditional library practice, their name is derived from their call numbers.[2]

John Merro, copyist

Although it is known that John Merro copied the manuscript known today as Drexel 4180–4185, little biographical information about him has surfaced. First mentioned in a passing reference in 1609, it is known that he was a singer at Gloucester Cathedral. Based on inscriptions in the two manuscripts in the British and Bodleian libraries, Pamela Willetts observed that Merro had an interest in theology.[3] Other references identify him as witness to the will of Ann Tomkins (wife of Thomas Tomkins, step-mother of famed composer also named Thomas Tomkins, and mother of John, Robert and Giles) as well as having taught viol to children. (He is probably not the John Merro who married Elizabeth Hiam on April 26, 1627.) Merro's will is dated December 10, 1638, giving bequests to various family members. He died March 23, 1639, with his will going into effect on April 20, 1639. The will of his wife Elizabeth is dated September 9, 1645. In addition to giving bequests, she asked that she be buried next to her husband in the Cathedral. She died November 13, 1645, and her will was enacted in December of that year.[4]

General information on Merro's manuscripts

Three manuscripts can be identified as coming from Merro's hand:

- Drexel 4180–4185 (New York Public Library)

- Additional 17,792-6 (British Library)

- Mss. Mus. Sch. D.245-7 (Bodleian Library)

Drexel 4180–4185 is the largest of the three collections and has the most diverse repertory.[5] Based on its contents, Monson estimated the date of Drexel 4180–4185 to be between 1615 and 1625, making it the earliest of the three manuscripts attributed to Merro.[6] Both Add. 17792-6 and D 245-7 contain of inscriptions by Merro indicating the manuscripts belonged to him. Such an indication is lacking in Drexel 4180–4185 suggesting that the partbooks were not part of Merro's personal collection but used by the cathedral, "made for informal use of choirmen and their friends."[7] However, they are not listed on the Gloucester Cathedral's inventory, indicating either that they were not part of that collection, or were removed before the inventory was made.

David Fallows hypothesized that the partbooks might have been the possession of Gloucester organists.[7] At the cathedral it was the organist's responsibility to copy music for use by the choir. Merro, who received an annual salary, might have been commissioned to do the copying because of his legible hand, though not necessarily in an official capacity. Unfortunately he was not accurate as many errors exists in the partbooks.[3][7]

Physical details

The original covers to the partbooks were lost when the volumes were rebound in 1950.[7] However, Rimbault, who printed some of the works in his A Collection of Anthems for Voices and Instruments by Composers of the Madrigalian Era, included the following note observing the now-lost bindings in that volume's preface:

This valuable set of ancient Part-books consists of six small oblong volumes in the original binding, and with the Arms and Badge of Edward the Sixth stamped on the sides … The writing commences in the reign of Edward the Sixth, and ends in that of Charles the First, the last composition entered being an Ode composed by Orlando Gibbons for the marriage of that king with the princess Henrietta Maria.[8]

Even without seeing the covers Ashbee noted several obvious errors in Rimbault's account.[7] Rimbault said the final work is an ode composed by Gibbons, but Ashbee noted it is a fantasia. Ashbee notes that the coat-of-arms could not have been that of Edward VI, although it suggests one from Gloucester, as well as ownership subsequent to that of Merro.[7]

Although Monson suggested the dates of 1615-1630, Fallows felt the earliest part of the span is the more correct. Based on his study of the paste-down flyleaves, he felt that the collection was bound no later than 1620 in Oxford.[9] Ashbee suggests dates of 1615-1625 and agrees that the earliest dates are more likely.[7]

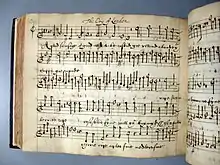

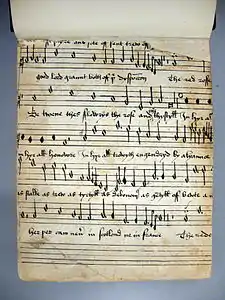

The physical layout of music resembles that of the manuscripts Christ Church MSS 984-8 (The Dow Partbooks) and British Library Add MS 22597. This might have been a conscious decision on Merro's part to acknowledge the music's historic nature by maintaining the appearance of an archaic manuscript.[10] In the cantus partbook (Drexel 4180), this archaic style can be seen on folios 1-16v, 18v-38v, 40-43, 54v-57 and 64v-68. To Monson this represents the oldest layer of the partbooks.[10]

Dating

Monson notes that the group of madrigals by Tomkins (leaves 124v-138) apparently come from Tomkin's 1622 publication.[11] The inclusion of Byrd's "O Lord make thy servant James" indicates it was entered before 1625. Thus Drexel 4180 suggests dating of 1622-25 for its final entries.[12]

The date when Merro began the collection is more difficult to determine. The publication of Amner's "Sacred Hymns" suggests a date no earlier than 1615.[13] Although Brett thought Merro might have begun copying his collection around 1600,[14] 1615 is the more likely date for when the collection was begun.[12]

Provenance

Possibly once having been in the possession of its copyist, John Merro, the whereabouts of the partbooks is unknown until the 19th century. Philip Brett mentions annotations he attributed to Matthew Hutton,[14] but Monson believed Brett was mistaken,[12] for the only annotations appear to be by a contemporary librarian.[15] The first indication of the partbooks comes from a nineteenth-century owner and musicologist Edward F. Rimbault. From whom he obtained the partbooks is revealed by the title of the publication in which he printed a few of the selections: A Collection of Anthems for Voices and Instruments by Composers of the Madrigalian Era Scored From a Set of Ancient M.S. Part Books Formerly in the Evelyn Collection.[16] The opening line of Rimbault's preface reads:

The following collection of anthems by Este, Forde, Weelkes, and Bateson, have been scored from a manuscript set of part-books formerly in the possession of the celebrated John Evelyn, and now forming one of the many musical rarities in the library of the Editor.[8]

Despite Rimbault's acknowledgement of John Evelyn in the title and in the first line of the preface, Monson and Ashbee had problems with Rimbault's account, possibly because of the previously mentioned errors.[7] Monson observed Rimbault said that the books were "formerly in the possession of the celebrated John Evelyn." Yet they didn't appear in Evelyn's own manuscript catalog nor do they carry Evelyn's ownership mark.[17][18] Ashbee admits the possibilities that the partbooks might have been given away prior to the creation of Evelyn's catalog, but noted that no mention of Evelyn is in the auction catalog of Rimbault's library.[19]

Since Merro was living in Gloucester, Fallows hypothesized that the partbooks were probably acquired by Edward F. Rimbault from someone living in that region. He views John Stafford Smith as the likely candidate since his father, Martin Smith, was organist at Gloucester Cathedral from 1739 to 1781.[20] Ashbee notes that after his death, Smith's library was sold piecemeal which would have simplified acquisition.[19] (Rimbault acquired other works from Smith, such as Drexel 4175.)

After Rimbault's death in 1876, the partbooks were sold as part of his estate.[21] They were one of about 600 lots purchased by Philadelphia-born financier Joseph W. Drexel (through his agent Joseph Sabin[7]), who had already amassed a large music library. Upon Drexel's death, he bequeathed his music library to The Lenox Library. When the Lenox Library merged with the Astor Library to become the New York Public Library, the Drexel Collection became the basis for one of its founding units, the Music Division. Today, Drexel 4180–4185 is part of the Drexel Collection in the Music Division, now located at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

Notation

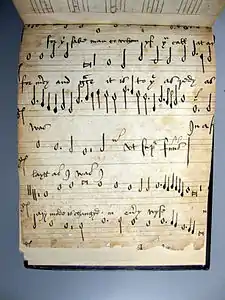

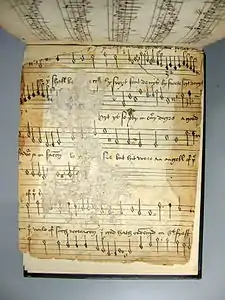

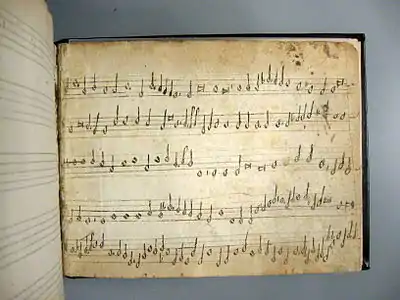

Monson notes that while some of Merro's scribal characteristics remain consistent through the six partbooks (the writing of treble, bass and c-clefs), other details differ both in music and in text underlay and the way in which they are written. For music, he ranges from the more old-fashioned square notation to the more contemporary use of rounded noteheads. In writing of text, his handwriting ranges from a stiff secretarial hand to a florid italic.[22] The square music notation combined with the secretarial hand of text appears mostly in older works, the four- and five-part sacred works by Tallis and his generation. Monson remarks on the appropriateness of such notation applying to an older generation of Elizabethan composers.[22] He notes that works by Byrd included in the collection appear to be written in a more archaic style, describing it as "a gesture towards decorum in penmanship and towards a historical sense which he [Merro] seems to possess."[10]

In the last hundred leaves Monson observes a preponderance of rounded notation and less use of the secretarial script.[11] This is most obvious in the annotations of "5 voc" and "6 voc." Monson believes these to be the "latest layer" in Drexel 4180–4185. Based on the last few vocal entries, Monson suggests they may have been completed in conjunction with work commencing on Merro's next work, Add. 17792.[11]

Despite variances, Monson felt that Merro was the sole copyist of the six partbooks and that the changes are due to his writing the books over the course of a dozen years.[22]

Both Willetts and Ashbee noted many errors in Merro's musical text.[3][7]

Music content

Monson hypothesized that Merro's intention was compiling a collection of serious vocal music.[17] He based this conjecture on the presence of more than 70 full anthems in four and five parts, quite a large number. Of the modern entries (aside from those written by local composers), most are composed by John Amner and Thomas Tomkins whose style relates more to the older composers (such as Thomas Tallis and John Mundy) than of contemporaneous ones (such as Michael East). Monson deduces that Merro's curation can be seen as an act of preservation since the repertory he favored was quickly falling out of favor.[17]

After the consort song, the English madrigal is the next most prominent genre.[17] Rather than distributing the madrigals throughout the collection, Merro groups them together, selecting what are known as the most popular and most serious, whose sources are from four publications:

- Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622) by Thomas Tomkins - 16[23]

- Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598) by Thomas Weelkes – 14

- The First Set of English Madrigals (1598) by Wilbye – 13

- Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601) - 7

Monson observed the large number of works by Tomkins and suggests the reason could be due to the proximity of Worcester (where Tomkins was organist) to Gloucester (where Merro resided). Acknowledging the popularity of Weelkes and Wilbye, Monson was struck by the lack of any works by Thomas Morley in Merro's collection. This suggested to Monson that the composer's popularity was only temporary and was quickly forgotten. There are also no works by Orlando Gibbons—unusual considering the 1612 publication of his The first set of madrigals and mottets of 5 parts, apt for viols and voyces. (According to Monson, "virtually all scribes" similarly ignored Gibbons's works.[23])

Monson observed a significant number of Italian madrigals with English texts: 11 works from Musical Transalpina (1588), 6 from Italian Madrigals Englished (1590), and 2 from Musical Transalpina II (1597).[23] Luca Marenzio is the most popular of Italian composers represented by ten compositions, followed by the inclusion of four by Ferrabosco. The first Italian madrigal to be entered is by William Byrd, followed by Marenzio's "Every singing byrd" (which Monson hypothesized might be a tribute to the composer William Byrd).[23] All remaining Italian madrigals are without text except for their titles, an attribute to be found in other English manuscripts of the time. Monson attributed this lack of Italian texts to the inability to handle the language. He noted that in some cases works are included without their titles (such as on folios 62v-64v), presumably as they were intended for viols rather than voices. The inclusion of works such as those by Hassler suggests that Merro's interest in the madrigal extended to more unusual examples than those of copyists of similar English manuscripts,[23] even though he was apparently not concerned with preserving the integrity of the works as madrigals.[24]

Beginning at 139v Merro added another section of Italian works, this time including works for up to eight voices. Monson hypothesized that Merro must have had access to the three volumes of Gemmae Musicalis (published in 1588, 1589, and 1590) which would be the explanation for inclusions of the works on leaves 139v-149r.[24] The two isolated Italian madrigals, "Dolorosi martir" by Marenzio and Tutt'eri foco by Pallavicino were apparently entered as afterthoughts on what were blank leaves.[24]

For the Latin motets, Merro focused on Englishmen of the generation of Tallis (died 1585), Shepherd (active in the 1550s) and Mundy (died 1591). Merro copied these motets at a time when the composers had been dead for several decades which can explain why many are listed anonymously or have incorrect attributions.[24] Monson claimed that the motets by Lassus and Clemens non Papa were late additions. That they appear with no text save for their titles provided Monson with the evidence of Merro's "strangely insular attitude toward foreign composers in whatever language their works may appear."[24]

Music for voices and viols play only minor importance in the partbooks which could be taken as a sign of the difference between musical life in urban London (where the consort song has greater prevalence in existing sources) and that in provincial Gloucester.[24] The most significant composer of the consort song in the collection is Byrd; the collection contains 4 works from published sources as well as two unpublished songs.[25][26] The two unpublished songs by Byrd are"Come pretty babe" (the manuscript contains an attribution to Byrd) and "Delight is dead." Of the three consort songs ("Abradad," "Farewell the bliss" and "Come, Charon, come"), the latter two have no composer attributions.[25] Viewed as a whole, Merro's solo consort song repertory appears retrospective and antiquated (Monson calls it "ancient").[25] The partbooks contain no evidence of newer compositional approaches such as the lute ayre.[25]

In the works copied for viols with solo and chorus, there is evidence of Merro's bending toward contemporary taste, most conspicuously in the works by John Amner. Two works by Michael East, "When Israel came out of Egypt" and "Sing we merrily" are not copied from the printed editions (which appeared in 1610 and 1624 respectively) but from earlier manuscript versions in secular sources. These two verse anthems in addition to "Rise O my soul" (Monson added "perhaps the most popular Jacobean verse anthem to appear in secular sources") are the only verse anthems taken from manuscript sources to appear in Drexel 4180–4185.[25]

Another sign of contemporary taste is the inclusion of works containing street cries: "The country cry" by Richard Dering, "The London cry" by Orlando Gibbons and the anonymous "The Cry of London."[27] Merro's version of Gibbons's "The London cry" differs from the one printed roughly contemporaneously in Thomas Myriell's "Tristitiae Remedium" (1615). In Drexel 4180 as well as Add. 29427, the two sections are in reverse. This is rectified in two later manuscripts, Add. 29372-7 and Add. 17792-6 (the latter manuscript also copied by Merro).[27]

Merro's version of Gibbons' "The London cry" is of interest. Though text underlay of these cry works were subject to variation, Merro's copy in Drexel 4180 is particularly extensive and occasionally explicit. An example concerns the depiction of a horse. Whereas one source gives a line as "She hath but on eye, and that is almost out, with a hole in he ear and a slit in her nose"; Add. 37402-6 has it as "...and a hole in her hip or there about." Merro's version in Drexel 4180–4185 reads: "She hath but on eye, and that is almost out, and a hole in her arse and there your snout." The explicit lines in Merro's version of Gibbons's popular work suggest a counterbalance to the conservative taste otherwise derived from the selection of works.[27]

Most of Merro's choices eschew interest in London or the court and reflect local and provincial taste. The exception is Gibbons's "Do not repine fair sun" which was written for the visit of James I to Scotland in 1617. Monson was perplexed as to how a work so closely connected with the court could find its way into Merro's collection. Although Monson suggested that Joseph Hall (1574-1656), a well-traveled clerk might have been the source, he was reluctant to accept the connection.[27]

As Merro worked for Gloucester Cathedral, it is not surprising to find works in Drexel 4180–4185 by composers active in the same vicinity. Those composers associated with a place in the manuscript are all from the West of England:

- "Mr Hugh Davies of Hereford"

- "Mr Tomkins of Woster"

- "Smith of Salop" [Shropshire]

- "Smith of Gloucester"

Except for Richard Nicholson, the more obscure composers are west countrymen and appear in other sources stemming from that region.[15][28]

Ashbee surmised that the repertoire of Drexel 4180–4185 was not dictated by Merro but rather the availability of sources by those performing it. The recreational nature of the collection is confirmed by the inclusion of non-liturgical works.[29]

Monson strove to understand the manuscript's grouping by looking at its structure and creation. The collection begins with four-part works (on leaves 1r through 23r), while five-part works begin on 23v with Byrd's "O God, give ear," "one of the most famous of all consort songs."[30] Monson believed that both the four-part and five-part sections were begun at the same time.[10] Monson guessed that the section beginning on 54v (opening with Byrd's "Lullaby") might have been intended as the start of another section containing consort songs.,[10] and that Merro began these three sections at the same time.[30] A fourth section (containing full anthems for five to eight voices) was begun on 64v.

Each of these sections was preceded by a few blank pages. Based on the blank page before 40r, Monson hypothesized that Merro planned a section of five-part madrigals. This explains the blank pages leading up to the next section containing Palestrina's Vergine cycle on page 40r.[30]

Beginning on 158v of 4180 ("O sing unto the Lord" by Amner) is a final group of full anthems, haphazard mixture of five- to twelve-parts. (It is also present in Add. 17792, although in that manuscript Merro maintained section division by a5, a6 and a7.[11]) Merro was constrained by the organization of Drexel 4180–4185, so when he came up to William Randall's 6-part "Give sentence with me," he could not enter it after 167v so he went back and inserted it on half of 122v. The same situation occurred with Thomas Ford's 5-part "Let God arise" backtracking to enter it beginning on 123v. Thus the Randall and Ford works form the demarcation of madrigals by Weelkes (prior to 122v) and Tomkins (following on 125v).[11]

Later insertions such as those by Randall and Ford were the clues to Monson that aided in his dating of the partbooks.[11] He notes that the group of madrigals by Tomkins on folios 124v through 138r come from the published collection "Songs of 3. 4. 5. & 6. parts".[31] Monson makes note of Thomas Bateson's seven-part "Holy Lord God almighty," his only extant sacred work.[11][32]

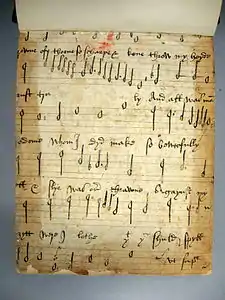

Paste down endpapers

When the partbooks were rebound in 1950, it was discovered that the pastedown endpapers were made from discarded music manuscripts from the sixteenth century. Rather than be cross at the willful destruction of such leaves embedded in old bindings, Fallows asserted that we should be thankful to the collectors who sought to decorate their books using these otherwise discarded fragments.[33] Being that there are six partbooks, there should have been twelve pastedowns (two for each volume, one each for the front and back endpapers), but only nine were found.[34] These were first documented by John Stevens (who said that they were brought to his attention by Thurston Dart).[35] Of these nine fragments (some of which contain more than one composition), Stevens counted fifteen separate works, four which appear in the British Library manuscript Add. 5465, the Fayrfax manuscript (F19, F24, F37, F40), and one ("The bella, the bella") with the 1530 publication XX Songes. Two of the numbers from the Fayrfax manuscript (F19 & F24) correspond to 2 sides of a leaf fragment in the Fitzwilliam Museum. Also, John Heywood's name can be linked indirectly with songs nos. 2 and 5.[35]

After Stevens' brief 1961 study there was no substantive examination of the fragments until 1993 when David Fallows published his study.[36] Fallows takes his point of departure the song "Somewhat musyng." This fragment, designated "A3" by Fallows, is discernible on the back pastedown of Drexel 4185. Fallows recognized that fragment is the bottom half of a leaf now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Music MS 1005.[37] This song has two complete manuscript copies, both in sources which are considered among the main sources of early Tudor song, British Library Add. 5465 known as the "Fayrfax Manuscript" and the Henry VIII Manuscript, British Library Add. 31922. Writers have considered it one of the most widely distributed Tudor songs, appearing in three sources. [38][39]

The binding of the Drexel partbooks was replaced by the library in 1950, strongly suggesting that the original binding was in poor shape. Based on the pattern of the original binder, Fallows hypothesized that the Fitzwilliam Museum fragment was originally in the front endpaper of Drexel 4185. Fallows notes that the original choirbook source for the fragments was 29 x 21 cm. and that, when folded, nearly matches the size of the Drexel fragment, save for a 2 millimeter sliver.[34] Fallows hypothesized that a fragment in Cleveland might have been also been part of the same leaf from which the Drexel and Fitzwilliam fragments once belonged to. [33]

Although the original binding was lost when NYPL rebound the partbooks in 1950, some information can be ascertained based on the Bodleian fragments. These fragments come from the binding of the works of Gervase Babington published in 1615. The copy in the Bodleian Library was enumerated in Thomas James's 1620 catalog of the Bodleian Library. The Bodleian Day Book for 1613-1620, a log of daily happenings at the library, recorded that it was sent to the binder John Adams on October 2, 1615, confirmed by the type of binding used from 1615 on. The related fragment stem from a book published in 1611. J.B. Oldham identified the binder as Francis Peerse, the binder at the Bodleian Library from 1613 until his death in 1622. Though Monson estimated the date of the partbooks at about 1615 through 1630, Fallows drew the conclusion that the partbooks were bound in Oxford no later than 1620. (This does not preclude that musical works were copied into the books after they had been bound.) Fallows mentions that although using fragments in bindings ceased in London around 1540 and in Cambridge around 1570, it remained the custom in Oxford until around 1620.[9]

Whereas fragment A3 is in oblong format, fragment B is in upright format, suggesting that the two fragments come from different manuscripts. Fragment B contains parts of two songs, both of which are in the Fayrfax manuscript. The second one contains the opening line from Davy's "A blessid Jhesu" (Fayrfax ms. No. 37). The recto and top of the verso were designated by Stevens as two different songs, although he left open the possibility that they could be from the same work. Fallows said they are two stanzas of the same carol and proposes that Fragment B contains the second and third stanzas.[33] This leads Fallows to hypothesize that fragment B was not from a choirbook, but from a discantus partbook, because recto and verso of the fragment are a continuous discantus line, leading into another song.[40]

The fragments present a varying array of scribal styles which could represent a single scribe engaging in different styles.[41] While similar, it is questionable whether the handwriting of B is the same as A3.[40] Fallows believes the handwriting is the same as another early Tudor fragment now in the Bodleian Library, Mus. D. 103. This fragment is two bifolia taken from an early seventheenth-century binding. The fragment from the Bodleian Library indicates that the scribe used music paper ruled with seven staves. As this fragment shows the full height of the page, it is the proof that it could not be cut in two in order to be used as the pastedowns for the Drexel manuscript. This also means that on Drexel fragment B one staff is missing from the top which corresponds to the beginning of the third stanza of the song "In a slumbir." Departing from Stevens's point of view Fallows recognizes that the original leaf would have been the verso (now lost) facing fragment B. This helps understanding the other Drexel fragments.[9]

Fragment C is also upright (as is fragment B). It is also from a discantus partbook, probably the same one as fragment B, bound into the other end of the Drexel partbook. It appears to have had seven staves on the page. The verso contains beginning of the discant to "Jhoone is sike" by Davy (Fayrfax no. 40). Six staves are visible and a fragment of the text indicates it began there. The recto contains the end of a carol celebrating the wedding of James IV of Scotland to Margaret (Henry VIII's daughter) in 1503.[42] Stevens had observed that the tessitura of fragment C is in the alto range. Its recto and verso are apparently two different hands, neither of which is the same handwriting as fragment B.[41]

Fragment D appears to come from a bassus partbook. Fallows entertains the possibilities that B, C, and D are the hand of a single scribe and that the fragments come from two sources, a choirbook and a set of three partbooks: fragments B, C, and H are from the discantus, fragment G from the tenor and fragment D from the bassus.[41]

Fragment E contains a portion of John Taverner's "La bella la bella." Because this song had been published in XX songes (London, 1530), it provides a context for it and the other fragments. Dating from a period later than fragments B or C,[41] there is a possibility that this fragment is from the same discantus partbook as fragments B and C. If so, that suggests a date of 1510-1519—a date compatible with Taverner's "La bella la bella" as well as the later Henry VIII manuscript version of Fayrfax's "Somewhat musying" that is part of fragment A.[43] As originally noted by John Ward, fragment F apparently was once part of the leaf that is now in Cleveland (no. 15b), originally facing Drexel A2.[44] Although ultimately unprovable, Fallows argues that, save for fragment A, all other fragments probably stem from a single set of partbooks. These partbooks were probably copied around 1515 (a date based on the inclusion of "La bella la bella").[44]

The explanation of fragments B and C help in understanding fragment F. The music on the two pages has the same music with different texts, leading to the conclusion that it is two stanzas of the same musical work. As it appears to be a single voice moving from recto to verso, the assumption can be made that this is also from a discantus partbook, even though this one has only five staves per page (whereas the previous fragments indicated seven staves).[43]

Fallows concludes by saying there are two significant issues which the Drexel fragments reveal. They show the existence of the more florid singing style, dating from about 1500, which was known only through the Fayrfax manuscript and the publication XX songes. In other words: the simpler style prevalent in the Henry VIII manuscript (from about 1515) did not replace the florid style, but the two existed simultaneously, demonstrated by the Drexel fragments. The second significant issue suggests that Oxford was a likely center of song production. Fallows concludes with the hope for editions of unpublished music which will move knowledge toward a clearer understanding of the history of English song.[44]

List of contents

The partbooks

This table is based on Monson.[45] r=recto; v=verso.

| Title | Composer | Idiom | Cantus 4180 | Altus 4181 | Tenor 4182 | Quintus 4183 | Sextus 4184 | Bassus 4185 | Appearance in contemporary prints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O Lord the maker | William Mundy | full anthem | 0v | 0v | 1v | 1r | |||

| O Lord give thy holy spirit | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 1r | 1r | 2r | 1v | |||

| Give alms | [anonymous] | full anthem | 1v | 1v | 2v | 2r | |||

| My God look upon me | Mr. Smith of Salop | full anthem | 2v | 2v | 3v | 2v | |||

| If ye love me | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 3v | 3r | 4r | 3V | John Day, Certaine Notes (1560) | ||

| I give you a new commandment | John Sheppard | full anthem | 3v | 3v | 4v | 3v | John Day, Certaine Notes (1560) | ||

| Hear the voice | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 4v | 4v | 5v | 4v | John Day, Certaine Notes (1560) | ||

| Let us now laud | William Mundy | full anthem | 5r | 5r | 6r | 5r | |||

| A new commandment | William Mundy | full anthem | 6r | 6r | 7r | 5v | |||

| This is my commandment | [William Mundy/Thomas Tallis/Johnson] | full anthem | 6v | 6v | 7v | 6r | |||

| If ye be risen | Christopher Tye | full anthem | 6v | 7r | 8r | 6v | |||

| Rejoice in the Lord | N. Strogers | full anthem | 7v | 7v | 8v | 7v | |||

| A new commandment | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 8v | 8v | 9v | 8r | |||

| Submit yourselves | John Sheppard | full anthem | 9r | 9r | 10r | 8v | John Day, Certaine Notes (1560) | ||

| He that hath my commandment | William Mundy | full anthem | 9v | 9v | 10v | 9r | |||

| He that hath my commandment | T. Coste | full anthem | 10r | 10r | 11v | 9v | |||

| Behold it is Christ | William Mundy | full anthem | 10v | 10v | 12r | 10r | |||

| Praise the Lord | William Mundy | full anthem | 11r | 11v | 12v | 10v | |||

| O Lord from us | [anonymous] | full anthem | 11v | 12v | 13v | 11r | |||

| I will always give thanks | [anonymous] | full anthem | 12v | 12v | 14r | 12r | |||

| This sweet and merry | William Byrd | full anthem | 13r | 13r | 14v | 12v | Italian Madrigals Englished (1590), no. 8 | ||

| Every singing byrd | Luca Marenzio | full anthem | 14r | 14r | 15v | 13r | Italian Madrigals Englished (1590), no. 6 | ||

| When first my heedless | Luca Marenzio | full anthem | 15r | 15r | 16v | 14r | Italian Madrigals Englished (1590), no. 1 | ||

| O merry world | Luca Marenzio | full anthem | 15v | 15v | 17r | 14v | Italian Madrigals Englished (1590), no. 2 | ||

| Zephyrus [breathing] | Luca Marenzio | full anthem | 16r | 16r | 17v | 15r | Italian Madrigals Englished (1590), no. 4 | ||

| Fair shepherd's queen | Luca Marenzio | full anthem | 16v | 16v | 18r | 15v | Italian Madrigals Englished (1590), no. 5 | ||

| Circumdederunt me | Jacob Clemens non Papa | 17r | 17r | 18v | 16r | ||||

| Quoniam tribulatio (ii) | Jacob Clemens non Papa | 17v | 17v | 19r | 16v | ||||

| Saint Marie now (i) | John Amner | full anthem | 18v | 19r | 20r | 18r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 9 | ||

| At length (ii) | John Amner | full anthem | 18v | 19r | 20r | 18r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 10 | ||

| But he the God of love (iii) | John Amner | full anthem | 19r | 19v | 20v | 18v | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 11 | ||

| Sweet are the thoughts | John Amner | full anthem | 19v | 20r | 21r | 19r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 7 | ||

| Woe is me that I am | John Amner | full anthem | 21r | 22r | 20r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 12 | |||

| Come let's rejoice | John Amner | full anthem | 21r | 21v | 22v | 20v | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 8 | ||

| O greif, if yet | Baldassare Donato | full anthem | 21v | 22r | 23r | 21r | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 5 | ||

| My heart, what hast | Thomas Morley | full anthem | 22v | 23r | 24r | 21v | Canzonets, or little short songs to fovre voyces (1597), no. 8 | ||

| Still it frieth | Thomas Morley | full anthem | 23r | 23v | 24v | 22r | Canzonets, or little short songs to fovre voyces (1597), no. 9 | ||

| O God, give ear | William Byrd | full anthem | 23v | 24r | 25r | 22v | 1r | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 1 | |

| O mortal man | William Byrd | full anthem | 24r | 24v | 25v | 23r | 1v | ||

| O Lord I bow the knees | William Mundy | full anthem | 25r | 25v | 26v | 23v | 2v | ||

| Grant unto us | N. Strogers | full anthem | 26r | 26v | 27v | 24v | 3av | ||

| Wipe away my sins | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 26v | 27r | 28r | 25v | 3b | ||

| Deliver me from mine enemies | Robert Parsons | full anthem | 27v | 28r | 29r | 26v | 4r | ||

| Lord, who shall dwell | Robert White | full anthem | 28r | 29r | 29v | 27r | 4v | ||

| Prevent us O Lord | William Byrd | full anthem | 29v | 30r | 31r | 28v | 6r | ||

| Blessed by thy name | Thomas Tallis | 30r | 30v | 31v | 29r | 6v | |||

| Set up thyself | Mr. Smith of Gloucester | full anthem | 30v | 31r | 31v | 29v | 7r | ||

| Almighty God, the fountain | Mr. Tomkins of Woster | full anthem | 31r | 32r | 33v | 30r | 7v | ||

| I will sing unto the Lord | John Amner | full anthem | 32r | 33r | 32v | 31r | 8v | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 18 | |

| The heavens stood | John Amner | full anthem | 32v | 33v | 33r | 31v | 9r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 15 | |

| He that descended | John Amner | full anthem | 33r | 34v | 34v | 32r | 9v | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 17 | |

| Now doth the city | John Amner | full anthem | 33v | 35r | 35r | 32v | 10r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 16 | |

| When Israel (i) | Michael East | verse anthem | 34r | 35v | 35v | 33r | 10r | The third set of bookes... (1610), no. 4 | |

| What aileth thee (ii) | Michael East | verse anthem | 34r | 35v | 35v | 33r | 10r | The third set of bookes... (1610), no. 45 | |

| Rise O my soul (i) | William Simms | verse anthem | 35v | 36v | 36v | 34r | 11V | ||

| And thou, my soul (ii) | William Simms | verse anthem | 35v | 36v | 36v | 34r | 11V | ||

| To thee, O Jesu (iii) | William Simms] | verse anthem | 35v | 36v | 36v | 34r | 11V | ||

| Do not repine fair sun | Orlando Gibbons | verse anthem | 37r | 38r | 38v | 35v | 13v | ||

| Vergine bella | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | 40r | 41r | 43r | 39r | 17r | Il primo libro de madrigali (1581), no. 1 | ||

| Vergine saggia | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | 40v | 41v | 43v | 39v | 17v | Il primo libro de madrigali (1581), no. 12 | ||

| Vergine pura | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | 41r | 42r | 44r | 40r | 18r | Il primo libro de madrigali (1581), no. 13 | ||

| Vergine santa | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | 41v | 42v | 44v | 40v | 18v | Il primo libro de madrigali (1581), no. 15 | ||

| Vergine sol'al [mondo] | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | 42r | 43r | 45r | 41r | 19r | Il primo libro de madrigali (1581), no. 16 | ||

| Vergine chiara | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | 42v | 43v | 45v | 41v | 19v | Il primo libro de madrigali (1581), no. 18 | ||

| Vergine quante [lagrime] | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | 43r | 44r | 46r | 42r | 20r | Il primo libro de madrigali (1581), no. 19 | ||

| [Fantasia] the first | Thomas Lupo the elder | 43v | 44v | 46v | 42v | 20v | |||

| [Fantasia] the second | Thomas Lupo the elder | 44r | 45r | 47r | 43r | 21r | |||

| [Fantasia] the third | Richard Dering | 44v | 45v | 47v | 43v | 21v | |||

| [Fantasia] the fourth | Richard Dering | 45r | 46r | 48r | 44r | 22r | |||

| The white delightful swan | Orazio Vecchi | 45v | 46v | 48v | 44v | 22v | Musica Transalpina (1597), no. 1 | ||

| Cinthia [thy song] | Giovanni Croce | 46r | 47r | 49r | 45r | 23r | Musica Transalpina (1597), no. 4 | ||

| "Larissinall" [Le Rossignol] | Alfonso Ferrabosco | 46v | 47v | 49v | 45v | 23v | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 43 | ||

| When I would thee embrace | Giovanni Battista Pinello di Ghirardi | 47r | 48r | 50r | 46r | 24r | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 41 | ||

| When shall I cease | Noë Faignient | 47v | 48v | 50v | 46v | 24v | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 21 | ||

| I must depart | Luca Marenzio | 48r | 49r | 51r | 47v | 25v | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 22 | ||

| Susanna fair | Orlande de Lassus | 48v | 49v | 51v | 47v | 25v | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 19 | ||

| So gratious | Giovanni Ferretti | 49r | 50r | 52r | 48r | 26r | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 25 | ||

| In paradise | [anonymous] | consort song | 49v | 50v | 52v | 48v | 26v | 1v | |

| Delight is dead | William Byrd | consort song | 50r | 51r | 53r | 49r | 27r | ||

| Come pretty babe | William Byrd | consort song | 50v | 51v | 53v | 49v | 27v | ||

| Abradad | [anonymous] | consort song | 51r | 52r | 53v | 50r | 28r | ||

| Farewell the bliss | [anonymous] | consort song | 52r | 52v | 54v | 50v | 28v | ||

| Come, Charon, come | [anonymous] | consort duet | 53r | 53r | 55r | 51r | 29r | ||

| Lullaby (i) | William Byrd | consort song | 54v | 53v | 55v | 51v | 29v | Psalmes, Sonets and Songs (1588), no. 32 | |

| Be still (ii) | William Byrd | consort song | 54v | 53v | 55v | 51v | 29v | Psalmes, Sonets and Songs (1588), no. 32 | |

| Prostrate O Lord | William Byrd | consort song | 55v | 54v | 56r | 52r | 30v | Psalmes, Sonets and Songs (1588), no. 27 | |

| In fields abroad | William Byrd | consort song | 54r | 55r | 56v | 52v | 31r | Psalmes, Sonets and Songs (1588), no. 22 | |

| Constant Penelope | William Byrd | consort song | 55v | 55v | 57r | 53r | 31v | Psalmes, Sonets and Songs (1588), no. 23 | |

| O sing unto the Lord | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 56v | 56r | 57v | 53v | 32r | 2v/10v | |

| Sing we merrily (i) | Michael East | verse anthem | 57v | 57r | 58v | 54v | 33r | 3v | The Sixt Set of Bookes... (1624), no. 14 |

| Take the psalm (ii) | Michael East | verse anthem | 57v | 57r | 58v | 54v | 33r | The Sixt Set of Bookes... (1624), no. 15 | |

| Blow up the trumpet (iii) | Michael East | verse anthem | 58r | 57v | 59r | 55r | 33v | 4r | The Sixt Set of Bookes... (1624), no. 16 |

| Why dost thou shoot | John Wilbye | full anthem | 59r | 58v | 61r | 56r | 34v | 4v | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 30 |

| Of joys and pleasing pains | John Wilbye | full anthem | 59v | 59r | 61v | 56v | 35r | 5v | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 26 |

| My throat is sore | John Wilbye | full anthem | 60r | 59v | 62r | 57r | 35v | 6r | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 27 |

| O ye little flocks (i) | John Amner | verse anthem | 60v | 60v | 62v | 57v | 36v | 7r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 19 |

| Fear not (ii) | John Amner | verse anthem | 61v | 61r | 63v | 58r | 37r | 7v | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 20 |

| And they cry (iii) | John Amner | verse anthem | 62r | 61v | 64r | 58v | 37v | 8r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 21 |

| Lo how from heaven (i) | John Amner | verse anthem | 62v | 62v | 64v | 59r | 38r | 8v | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 22 |

| I bring you tidings (ii) | John Amner | verse anthem | 63r | 62r | 65r | 59v | 38v | 9r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 23 |

| A stranger here | John Amner | full anthem | 63v | 63r | 65v | 60r | 39v | 9v | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 24 |

| My Lord is hence removed | John Amner | verse anthem | 64r | 63v | 66r | 60v | 40r | 10r | Sacred hymnes Of 3. 4. 5 and 6. parts for voyces & vyols (1615), no. 25 |

| Sing joyfully | William Byrd | full anthem | 64v | 64r | 66v | 61r | 40v | 12v | |

| O God the proud | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 65v | 65r | 57v | 61v | 41v | 13v | |

| Christ rising (i) | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 66r | 65v | 68v | 62v | 43v | ||

| Christ is risen (ii) | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 66r | 65v | 68v | 62v | 43v | ||

| O Lord how long wilt thou | [anonymous] | full anthem | 67v | 67r | 69v | 63v | 44r | ||

| Salvator Mundi | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 68v | 68r | 70v | 64v | 45v | Cantiones Sacrae (1575), no. 1 | |

| Absterge Domine | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 69r | 68v | 71r | 65r | 46r | Cantiones Sacrae (1575), no. 2 | |

| Lamentations | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 70r | 69v | 72r | 66r | 47r | ||

| In resurrectione | William Byrd | full anthem | 71v | 71r | 73v | 67v | 48v | Cantiones Sacrae (1575), no. 17 | |

| Adolescentulus sum | William Mundy | full anthem | 72r | 71V | 74r | 67V | 49r | 15V | |

| Jerusalem plantabis | [anonymous] | full anthem | 73r | 72v | 75r | 58v | 50r | 16v | |

| Credo quod redemptor | Robert Parsons | full anthem | 73v | 73v | 75v | 69r | 50v | 17v | |

| O sacrum convivium | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 74r | 69v | 51r | Cantiones Sacrae (1575), no. 9 | |||

| [Homo] quidam fecit | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 74v | 74r | 76r | 70r | 51v | 18r | |

| In Nomine | William Byrd | 75r | 75v | 77v | 70v | 52r | In Nomine a5 No. 5 | ||

| In Nomine | Robert Parsons | 75v | 76r | 78r | 71r | 52v | |||

| In Nomine | Alfonso Ferrabosco | 58r[46] | 76v | 78v | 71v | 53r | |||

| In Nomine | "Brewster" | 58v | 77r | 79r | 72r | 53v | |||

| De la courte (part 1) | Robert Parsons | 59r | 78v | 79v | 72v | 54r | |||

| De la courte (part 2) | Robert Parsons | 59v | 77v | 80v | 73r | 54v | |||

| [Unidentified Italian madrigal] | [anonymous] | 62v | 79r | 81v | 73v | 55v | |||

| [Ma la fiamma de l'alma] | Hans Leo Hassler | 63r | 79v | 82r | 74r | 56r | Madrigali à 5. 6. 7. & 8. voci (1596) | ||

| [Musica e lo mio core] | Hans Leo Hassler | 61v | 80r | 82v | 74v | 56v | 18v | Madrigali à 5. 6. 7. & 8. voci (1596) | |

| [Unidentified Italian madrigal | [anonymous] | 63v | 80v | 83v | 75r | 57r | 19v | ||

| [Unidentified Italian madrigal | [anonymous] | 64r | 81r | 84r | 75v | 57v | |||

| [Care lagrime mie] | Hans Leo Hassler | 64v | 81v | 84v | 76r | 58r | Madrigali à 5. 6. 7. & 8. voci (1596) | ||

| Dolorosi [martir] | Luca Marenzio | 65r | 82r | 85r | 76v | 58v | |||

| Now must I part | Luca Marenzio | 65v | 82v | 85v | 77r | 59r | 20r | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 51 | |

| So far from my delight | Alfonso Ferrabosco | 66r | 83r | 86r | 77v | 59v | 20v | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 48 | |

| [She only doth not feel] | Alfonso Ferrabosco | 66v | 83v | 86v | 78r | 60r | 21r | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 49 | |

| I sung sometime | Luca Marenzio | 67r | 84r | 87r | 78v | 60v | 21v | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 56 | |

| [Because my love] | Luca Marenzio | 67v | 84v | 87v | 79r | 61r | 22r | Musica Transalpina (1588), no. 57 | |

| Laudate pueri | William Byrd | full anthem | 68r | 85r | 88r | 79v | 61v | 22v | Cantiones Sacrae (1575), no. 17 |

| Deus misereatur | John Sheppard | full anthem | 69v | 86r | 91r | 62v | 23v | ||

| Deus misereatur | Robert White | full anthem | 71r | 88r | 89r | 80v | 64r | 25r | |

| Domine non exaltatum | William Mundy | full anthem | 72v | 89v | 92v | 81v | 65v | 26v | |

| [Libera nos] salva | John Sheppard | full anthem | 73v | 90v | 93v | 82v | 66v | 27v | |

| [Libera nos] salva | John Sheppard | full anthem | 74r | 91r | 94r | 83v | 67r | 28r | |

| Esurientes | John Sheppard | 74r | 91v | 94r | 82v | 67r | |||

| Jerusalem surge | Clemens non Papa | 74r | 92r | 94v | 84r | 69r | |||

| Jerusalem surge, part 2r | Clemens non Papa | 75r | 92v | 95r | 84v | 69v | |||

| Veni electa mea (i) | Clemens non Papa | 75v | 93r | 95v | 85r | 70r | |||

| Audi filia (ii) | Clemens non Papa | 76r | 93v | 96r | 85v | 70v | |||

| Dum transisset | Thomas Tallis | full anthem | 76v | 94r | 96v | 86r | 68r | ||

| Cantate Domino | Richard Nicholson | full anthem | 77v | 94v | 97v | 86v | 71r | ||

| Blessed art thou that fearest | [anonymous] | full anthem | 78r | 95v | 98v | 87r | 71v | ||

| Veni in hortum | Orlande de Lassus | full anthem | 79r | 96v | 98r | 88r | 72v | ||

| Angelus ad pastores | Orlande de Lassus | full anthem | 79v | 97r | 100r | 88v | 73r | ||

| Sermone blando | William Mundy | 80r | 97v | 100v | 89r | 73v | |||

| Cante, cantate | Robert Parsons | 80v | 98r | 101r | 89v | 73v | 28v | ||

| Johnson's knell | Robert Johnson | 81r | 98v | 101v | 90r | 74r | |||

| Alas, alack, my heart is woe | [anonymous] | 8 [82?] | 99a | 102r | 91r | 75r | |||

| Holy, holy, holy | Robert Parsons | full anthem | 82v | 99av | 102v | 91v | 75v | ||

| All ye people, clap | William Byrd | full anthem | 83v | 99bv | 103v | 92v | 76v | ||

| O Lord turn thy wrath | William Byrd | full anthem | 84r | 100r | 104r | 93r | 77r | ||

| Bow thine ear (ii) | William Byrd | full anthem | 84v | 100v | 104v | 93v | 77v | ||

| Out of the deep | William Byrd | full anthem | 85v | 101v | 105v | 94v | 78v | ||

| Behold, how good and joyful | [anonymous] | full anthem | 86v | 102v | 106v | 95v | 79v | ||

| How long shall mine enemies | William Byrd | full anthem | 87v | 103v | 107v | 96v | 80v | ||

| O Lord, make thy servant, James | William Byrd | full anthem | 89v | 104v | 180v | 97v | 81v | ||

| O fools can you not | John Wilbye | full anthem | 90v | 106v | 109v | 98r | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 8 | ||

| Alas, what hope | John Wilbye | full anthem | 91v | 107r | 110r | 98v | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 9 | ||

| Lady, when I behold | John Wilbye | full anthem | 92v | 107v | 110v | 99r | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 10 | ||

| Thus saith my Cloris | John Wilbye | full anthem | 93v | 108v | 111v | 99v | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 11 | ||

| Adieu, sweet Amarillis | John Wilbye | full anthem | 94r | 109r | 112r | 100r | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 12 | ||

| Die, hapless man | John Wilbye | full anthem | 94v | 109v | 112v | 100v | 82r | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 13 | |

| I fall | John Wilbye | full anthem | 95r | 110r | 113r | 101r | 82v | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 14 | |

| Unkind O stay | John Wilbye | full anthem | 95v | 110v | 113v | 101v | 83r | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 20 | |

| Flora gave me | John Wilbye | full anthem | 96r | 111r | 114r | 102r | 83v | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 22 | |

| I sung sometimes | John Wilbye | full anthem | 96v | 111v | 114v | 102v | 84v | The First Set of English Madrigals (1598), no. 21 | |

| When David heard | Mr. Smith | full anthem | 97v | 112v | 115v | 103v | 85v | ||

| O give thanks | Nathaniel Giles | full anthem | 98r | 113r | 116r | 104r | 86r | ||

| Behold it is Christ | Edmund Hooper | full anthem | 99r | 114r | 117r | 105r | 87r | ||

| Rejoice in the Lord | Mr. Hugh Davies of Hereford | full anthem | 100r | 115r | 118r | 106r | 88r | ||

| O God, whom our offences | William Byrd | full anthem | 101v | 116v | 119v | 106v | 89v | ||

| Hear my crying | [anonymous] | full anthem | 102v | 117v | 120v | 107v | 90v | ||

| All people clap | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 104r | 119r | 122r | 108v | 92r | ||

| O Lord rebuke me not | [anonymous] | full anthem | 105r | 119v | 123r | 109v | 92v | ||

| Christ rising (i) | Edmund Tucker | full anthem | 106r | 121r | 124r | 110v | 94r | ||

| Christ is risen (ii) | Edmund Tucker | full anthem | 106r | 121r | 124r | 110v | 94r | ||

| The Country cry | Richard Dering | verse anthem | 107av | 122v | 125v | 112r | 95v | ||

| The London Cry (i) | Orlando Gibbons | verse anthem | 109v | 125v | 128r | 114v | 98v | ||

| A good sausage (ii) | Orlando Gibbons | verse anthem | 109v | 125v | 128r | 114v | 98v | ||

| The Cry of London | [anonymous] | verse anthem | 112v | 127v | 130v | 116v | 101v | ||

| O amica mea | Thomas Morley | 114r | 129r | 132r | 118r | 103r | |||

| All at once well met | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 114v | 129v | 132v | 118v | 103v | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 1 | |

| To shorten winter's | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 115r | 130r | 133r | 119r | 104r | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 2 | |

| Whilst youthful | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 115v | 130v | 133v | 119v | 104v | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 4 | |

| On the plains | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 116r | 131r | 134r | 120r | 105r | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 5 | |

| Hark all ye lovely | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 116v | 131v | 134v | 120v | 105r | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 8 | |

| Say, dainty dames | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 117r | 132r | 135r | 121r | 106r | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 9 | |

| In pride of May | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 117v | 132r | 135r | 121r | 106v | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 11 | |

| We shepherds sing | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 118r | 133r | 136r | 122r | 107r | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 17 | |

| I love and have my love | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 118v | 133v | 136v | 122v | 107v | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 18 | |

| Give me my heart | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 119v | 134v | 137r | 123r | 108r | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 7 | |

| Now is my Cloris | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 120r | 136a | 137v | 123v | 108v | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 22 | |

| Cease now delight | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 120v | 136av | 138r | 123v | 109r | 29v | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 24 |

| Come clap thy hands | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 121v | 135v | 139r | 124v | 111r | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 19 | |

| Phillis hath sworn | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 122a | 136a | 139v | 125r | 111v | Balletts and Madrigals to Five Voyces, with One to 6. Voyces (1598), no. 20 | |

| Give sentence with me | William Randall | full anthem | 122av | 136bv | 140r | 125V | 112r | 30V | |

| Let God arise | Thomas Ford | full anthem | 123v | 138v | 142r | 127v | 114r | ||

| To the shady woods | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 125v | 139v | 143v | 128v | 32r | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 13 | |

| Too much I once lamented | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 125r | 140r | 144r | 128v | 32v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 14 | |

| Come shepherds | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 126v | 140v | 144v | 129v | 33v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 15 | |

| Cloris, why still | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 127v | 141v | 145r | 130r | 334v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 16 | |

| See the shepherd's queen | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 128v | 142r | 145v | 130v | 35v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 17 | |

| Phillis now cease | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 129v | 142v | 146r | 131v | 36v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 18 | |

| When David heard | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 130v | 143r | 146v | 132v | 37v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 19 | |

| Phillis, yet see him | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 131v | 143v | 147v | 133r | 38v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 20 | |

| Fusca, in thy starry eyes | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 132v | 144v | 148v | 134r | 39v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 21 | |

| Adieu ye city prisoning towers | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 133v | 145v | 149r | 134v | 40v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 22 | |

| When I observe | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 134v | 146v | 149v | 135r | 115v | 41v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 23 |

| Music divine | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 135v | 147v | 150v | 135v | 116v | 42v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 23 |

| Oft did I marle | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 136v | 148v | 151v | 136v | 117v | 43v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 24 |

| Woe is me | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 137v | 149v | 152v | 137v | 118v | 44v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 25 |

| It is my well-beloved's voice | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 138v | 150v | 153v | 138v | 119v | 45v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 26 |

| Turn unto the Lord | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 138r | 151v | 154v | 138r | 120v | 46v | Songs of 3.4.5. & 6. parts (1622), no. 27 |

| A le quancie de rose | Andrea Gabrieli | 139v | 152r | 155r | 139v | 121r | 47r | Gemma Musicalis (1588) | |

| Ecco vinegio | Andrea Gabrieli | 140v | 152v | 155v | 140v | 121v | 47v | Gemma Musicalis (1588) | |

| Sacri [di Giove] | Giovanni Gabrieli | 141v | 153v | 156v | 141v | 122v | 48v | Liber secundus Gemmae musicalis (1589) | |

| O passi sparsi | Andrea Gabrieli | 142v | 154v | 157v | 142v | 123v | 49v | Liber secundus Gemmae musicalis (1589) | |

| A dio [dolce mia vita] | Giovanni Gabrieli | 143v | 155v | 158v | 143v | 124v | 50v | Gemma Musicalis (1588) | |

| D'un si bel foco | Alessandro Striggio | 144v | 156r | 159v | 144r | 125v | 51v | Gemma Musicalis (1588) | |

| Quei vinto dal furor | Andrea Gabrieli | 145v | 156v | 160v | 144v | 126v | 52v | Liber secundus Gemmae musicalis (1589) | |

| Ecco l'alma beata | Giovanni Croce | 146v | 157v | 161v | 145r | 127r | 53v | Liber secundus Gemmae musicalis (1589) | |

| Basti [fin qui] | Luca Marenzio | 147v | 158v | 162v | 145v | 127v | 54v | Liber secundus Gemmae musicalis (1589) | |

| Lieto godea [sedendo] | Giovanni Gabrieli | 148v | 159v | 163v | 146v | 128v | 55v | Gemma Musicalis (1588) | |

| O misero mio core | Giulio Eremita | 149r | 160r | 164r | 147r | 129v | 56v | Tertius Gemmae musicalis liber (1589) | |

| Hence stars | Michael East | full anthem | 149v | 160v | 164v | 147v | 130v | Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601) [unnumbered] | |

| With angel's face | Daniel Norcomb | full anthem | 150v | 161v | 165v | 148v | 131v | Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601), no. 1 | |

| Lightly she whipped | John Mundy | full anthem | 151v | 162v | 166v | 149v | 132v | Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601), no. 2 | |

| Long live fair Oriana | Ellis Gibbons | full anthem | 152v | 163v | 157v | 150v | 133v | Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601), no. 3 | |

| All creatures now | John Bennet | full anthem | 153v | 164v | 168v | 151v | 134v | Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601), no. 4 | |

| Fair Oriana | John Hilton | full anthem | 154v | 165v | 169v | 153v | 135v | Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601), no. 5 | |

| Sing shepherds all | Richard Nicholson | full anthem | 155r | 166v | 170r | 152v | 136r | Madrigales: The triumphes of Oriana, to 5. and 6. voices (1601), no. 9 | |

| Tutteri foco | Benedetto Pallavicino | 156v | 167v | 171v | 154v | 137v | |||

| [untitled] | [anonymous] | 157v | 168v | 172v | 155r | 138v | |||

| O sing unto the Lord | John Amner | full anthem | 158v | 169v | 173v | 155v | 139v | 57v | |

| Holy Lord God almighty | Thomas Bateson | full anthem | 160r | 170v | 175r | 156v | 140v | 60v | |

| Out of the deep | William Byrd | full anthem | 160v | 171v | 175v | 157v | 141v | 62r | |

| Rejoice in the Lord | Matthew Jeffries | full anthem | 162r | 172v | 176v | 158v | 142v | 63v | |

| O give thanks | John Mundy | full anthem | 163r | 173v | 177v | 159v | 144r | 64v | |

| Awake up my glory | ”Mr. Hugh Davies of Hereford” | full anthem | 164v | 175r | 179v | 160v | 145v | 65v | |

| Lord enter not into judgment | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 166r | 176r | 180v | 161v | 147r | ||

| O Lord arise | Thomas Weelkes | full anthem | 167v | 176v | 181r | 162v | 147v | 68v | |

| O praise the Lord, all ye heathen | Thomas Tomkins | full anthem | 166v | 177v | 181v | 163v | 148v | 69v | |

| Fantasia | William Byrd | 168v | 179v | 183v | 165v | 150v | 71v | Fantasia a6 No. 3 | |

| Fantasia | William Byrd | 169v | 180v | 184v | 166v | 151v | |||

| Dorick | John Bull | 181r | 185r | 167r | 152r | ||||

| Fantasia | Simon Ives | 184v | 185v | 167v | 72v | Fantasia a4 No. 2 | |||

| Fantasia | Simon Ives | 181v | 186v | 168v | 73v | Fantasia a4 No. 1 | |||

| Fantasia | John Jenkins | 182v | 187v | 169v | 74v | ||||

| Fantasia | John Jenkins | 183v | 188v | 170v | 75v | ||||

| Fantasia | Simon Ives | 185v | 189v | 171v | 76v | Fantasia a4 No. 4 | |||

| Fantasia | Simon Ives | 186v | 190v | 172v | 77v | Fantasia a4 No. 3 | |||

| Fantasia | Alfonso Ferrabosco | 187v | 191v | 173v | 78v | ||||

| Fantasia | [anonymous] | 169v | 188v | 174r | 152v | 79v | |||

| Fantasia 1 | Orlando Gibbons | 174v | 153v | 80v | |||||

| Fantasia 2 | Orlando Gibbons | 175v | 154r | 81v | |||||

| Fantasia 3 | Orlando Gibbons | 176v | 154v | 82v | |||||

| Fantasia 4 | Orlando Gibbons | 177v | 155r | 83v | |||||

| Fantasia 5 | Orlando Gibbons | 178v | 155v | 84v | |||||

| Fantasia 6 | Orlando Gibbons | 179r | 156r | 85r | |||||

| Fantasia 7 | Orlando Gibbons | 179v | 156v | 85v | |||||

| Fantasia 8 | Orlando Gibbons | 180v | 157r | 86v | |||||

| Fantasia 9 | Orlando Gibbons | 181r | 157v | 87v | |||||

| Fantasia 9 | Orlando Gibbons | 88v |

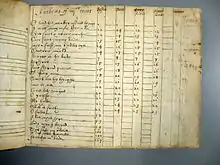

The pastedowns

This table is based on the articles by Stevens[47] and Fallows.[36] Neither author based their list on the integrity of the physical fragments but rather on their musical content. Thus, although there are nine fragments, both Stevens and Fallows enumerate more than nine items, as they discern more than a single musical work on some fragments. Fallows's list also includes designations for items in other libraries as he believes they were once joined with some of the Drexel fragments (fragments in other libraries are not included here). Stevens's list eschews use of bibliographic terms in identifying whether a fragment is recto or verso, or whether it comes from the front or the back of a volume.

| Call number | Location in volume | Recto or verso | Stevens's designation | Fallows's designation | Text | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drexel 4180 | front | recto | 3 | B | [c]rowne of thorne so scharpe & kene throw my heyd | Upright; Probably from a poem of Jesus's pleading |

| verso | 4 | B | for thy sake man to whom yf pu call at a[ny?]; [refrain]: In a f[orest?] laytt as I was I ...vt supra finis | Upright; probably from a poem of Jesus's pleading; possibly continuation of recto | ||

| 1 | D | "My mode is changyd in euery wyse" | "A blessed Jhesu, hough fortunyd this"; Fayrfax 37; bottom line of fragment | |||

| back | recto | 8 | C | The red rosse fayre and sote of sent | Upright; | |

| verso | 5 | C | "...y[ow] please alake good Jone what may...." | Upright; "Jhoone is sick and ill at ease"; Fayrfax 40; | ||

| Drexel 4181 | [front] | Lacking; perhaps "A8" now in Cleveland | ||||

| back | recto | 15 | D | Unidentified; perhaps related to the work on the verso | ||

| verso | 11 | D | ...thus hath mayd my payne | The first staff is a vocal work containing a bass part, possibly of a love song | ||

| 14 | D | Stevens: The remaining four staves are from an unidentified instrumental work, possibly related to 15; Fallows: untexted bassus part | ||||

| Drexel 4182 | [front] | Lacking; Fallows mistakes a leaf with empty staves as being a pastedown (it is really the beginning of the manuscript)[48] | ||||

| [back] | Lacking; perhaps "F3" now in Cleveland | |||||

| Drexel 4183 | front | recto | 10 | E1 | The bella, the bella we maydens, measures 23-52; this leaf has been tipped in the volume upside down | |

| verso | E1 | blank page | ||||

| back | recto | 7 | F2 | ...love shuld com. On euery syde the way she pryde | Fragment of an unidentified love song | |

| verso | 2 | F2 | "...whan I haue plesyd my lady now and than" | "All a green willow"; Song 25 (Stevens misidentifies this as belonging to Drexel 4184) | ||

| Drexel 4184 | front | recto | 10 | E2 | The bella, the bella we maydens | "We be maidens fair and gent," song 296 in XX songes, no. 6; measures 1-36 |

| verso | 10 | E2 | ...Syster loke pt ye be not forlorn | Continuation of The bella; Song 296; in XX songes, no. 6; treble: measures 53-66; alto: 53-61 | ||

| back | recto | 6 | F1 | ...[lo]kyng for her trew love long or that yt was day | fragment of a love song; bottom portion written over in a later hand | |

| verso | 13 | F1 | He þat smytyth hy... | He that smiteth with a stave of oak; refrain: Card lye down & whele stond styll / lett [ ] / [ ] tyll peny pot to þe nale tryll[49] | ||

| Drexel 4185 | [front] | Lacking; perhaps A3 bottom, now in Fitzwilliam Museum | ||||

| back | recto | 9 | A3 top | Sumwhat musyng and more morenyng in remembryng the unstedfastnes | tenor voice; misidentified by Stevens as being from 4183; Fayrfax 24; Henry VIII 107 | |

| verso | 9 | A3 top | to let it ouerpass and thynk þeron no more | First-second staves: conclusion of "Sumwhat musyng"; (third staff is blank) | ||

| - | A3 top | As solen as staytly as strange toward me as I of | Third-fourth staves: beginning of "As solemn as stately as strange toward me"[50] |

Works consulted

- Ashbee, Andrew (1967), "Lowe, Jenkins and Merro", Music and Letters, 48: 310–311

- Ashbee, Andrew (2013), "John Merro's Manuscripts Revisited" (PDF), The Viola da Gamba Society Journal, 7: 1–19, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-05, retrieved 2015-02-25

- Ashbee, Andrew; Thompson, Robert; Wainwright, Jonathan (2001). The Viola da Gamba Society index of manuscripts containing consort music. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754601302.

- Brett, Philip, ed. (1967). Consort Songs. Musica Brittanica. Vol. 22. London: Stainer and Bell.

- Drexel 4180–4185, New York: New York Public Library, 1942, OCLC 79468694

- Fallows, David (1993), "The Drexel Fragments of Early Tudor Song", Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 26: 5–18, JSTOR 25099433 (JSTOR access by subscription)

- Monson, Craig (1982). Voices and Viols in England, 1600-1650: the Sources and the Music. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press. pp. 133–58. ISBN 9780835713023.

- Rimbault, Edward F., ed. (1845), A Collection of Anthems for Voices and Instruments by Composers of the Madrigalian Era Scored From a Set of Ancient m.s. Part Books Formerly in the Evelyn Collection, London: Printed for the members of the Musical Antiquarian Society by Chappell, OCLC 23536116

- Stevens, John (1961), "Postscript: The Drexel Fragments", Music and Poetry in the Early Tudor Court, London: Methuen, pp. 426–28

- Willetts, Pamela J. (1961), "Music from the Circle of Anthony Wood at Oxford", British Museum Quarterly, 24: 71

Editions

Some material from Drexel 4180–4185 has appeared in modern editions:

- Beck, Sydney, ed. Nine Fantasias in Four Parts. New York: New York Public Library/C.F. Peters, 1947.

- Contains:

- Brett, Philip, ed. Consort Songs. Musica Britanica, volume 25. London: Stainer and Bell, 1967.

- Contains Alas, alack, my heart is woe, Farewell the bliss, In paradise, Come, Charon, come, ... The country cry

- Rimbault, Edward F., ed. A Collection of Anthems for Voices and Instruments by Composers of the Madrigalian Era Scored From a Set of Ancient m.s. Part Books Formerly in the Evelyn Collection. London: Printed for the members of the Musical Antiquarian Society by Chappell, [1845].

- Contains: Blow out (up) the trumpet, When Israel came out of Egypt, Let God arise, All people clap, Sing we merrily, Holy Lord God almighty.

References

- Peter Le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England 1549-1660 (New York: Oxford University Press), p. 99.

- Resource Description and Access, rule 6.2.2.7, option c (access by subscription).

- Willetts 1961, p. 74.

- Ashbee, Thompson & Wainwright 2001, p. 10.

- Monson 1982, p. 133.

- Ashbee 2013, p. 1.

- Ashbee 2013, p. 2.

- Rimbault 1845, p. 1.

- Fallows 1993, p. 9.

- Monson 1982, p. 135.

- Monson 1982, p. 137.

- Monson 1982, p. 138.

- John Amner, Sacred Hymns. Of. 3. 4. 5. and 6. parts for Voyces and Vyols (London : Edw. Allde, 1615).

- Brett 1967, p. 173.

- Monson 1982, p. 308.

- Rimbault 1845.

- Monson 1982, p. 139.

- Evelyn's catalog is located at Christ Church, cataloged as Catalogus Evelynianus 1687, MS 20a.

- Ashbee, Thompson & Wainwright 2001, p. 237.

- Fallows 1993, p. 13, footnote 13.

- Catalogue of the Valuable Library of the Late Edward Francis Rimbault, Comprising an Extensive and Rare Collection of Ancient Music, Printed and in Manuscript ... which will be sold by auction, by Messrs. Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge ... on Tuesday, the 31st of July, 1877, and five following days (London: Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 1877), p. 86, lot 1337.

- Monson 1982, p. 134.

- Monson 1982, p. 140.

- Monson 1982, p. 141.

- Monson 1982, p. 142.

- One of the songs mentioned by Monson is "Out of the deep" in versions for four and five voices, which Grove Music Online says is of doubtful authenticity. See Joseph Kerman and Kerry McCarthy, "Byrd, William" Grove Music Online accessed 19 January 2015 (access by subscription).

- Monson 1982, p. 143.

- Hugh Davies appears in the Gloucester bassus book, Christ Church 544-53, Bodleian manuscript Mus. D 162 and in Barnard sources Royal College of Music 1045-51 and Tenbury 791. Smith of Salop only appears in Ludlow SRO 356, MS.

- Ashbee 2013, p. 3.

- Monson 1982, p. 136.

- Thomas Tomkins, Songs of 3.4.5. and 6. parts, London: Printed for Matthew Lownes, John Browne and Thomas Snodham, 1622.

- In the 5th edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musician, Edmund H. Fellows says this work is thought to have been submitted by Bateson as a requirement for receiving his master's degree (Edmund H. Fellowes, "Bateson, Thomas," Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (New York : Macmillan, 1904-10), vol. 1, p. 498). There is no mention of this work's origin in New Grove, implying that Fellows's story lacked verification or was subsequently refuted (David Brown, "Bateson, Thomas," New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, New York: Oxford Music Online, accessed 18 January 2015. (access by subscription)

- Fallows 1993, p. 7.

- Fallows 1993, p. 6.

- Stevens 1961, p. 426.

- Fallows 1993.

- Fallows 1993, p. 5.

- Fallows 1993, p. 5-6.

- Fallows goes into depth explaining a misunderstanding that originally enumerated five sources for the song.

- Fallows 1993, p. 8.

- Fallows 1993, p. 10.

- John E. Stevens, Music & poetry in the Early Tudor Court (London: Methuen, 1961), p. 427.

- Fallows 1993, p. 11.

- Fallows 1993, p. 12.

- Monson 1982, p. 198.

- The contemporaneous page numbering restarts at 58 at this point in the cantus partbook.

- Stevens 1961.

- Fallows 1993, p. 15.

- http://www.cddc.vt.edu/host/imev/record.php?recID=1894/%5B%5D

- Footnote to The Digital Index of Middle English Verse

External links

Gallery

Endpapers

Drexel 4180 front recto

Drexel 4180 front recto Drexel 4180 front verso

Drexel 4180 front verso Drexel 4180 back recto

Drexel 4180 back recto Drexel 4180 back verso

Drexel 4180 back verso Drexel 4181 back recto

Drexel 4181 back recto Drexel 4181 back verso

Drexel 4181 back verso Drexel 4183 front recto

Drexel 4183 front recto Drexel 4183 front verso

Drexel 4183 front verso Drexel 4183 back recto

Drexel 4183 back recto Drexel 4183 back verso

Drexel 4183 back verso Drexel 4184 front recto

Drexel 4184 front recto Drexel 4184 front verso

Drexel 4184 front verso Drexel 4184 back recto

Drexel 4184 back recto Drexel 4184 back verso

Drexel 4184 back verso Drexel 4185 back recto

Drexel 4185 back recto Drexel 4185 back verso

Drexel 4185 back verso