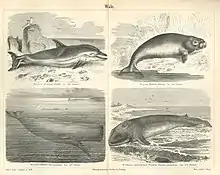

Drift whale

A drift whale is a cetacean mammal that has died at sea and floated into shore. This is in contrast to a beached or stranded whale, which reaches land alive and may die there or regain safety in the ocean. Most cetaceans that die, from natural causes or predators, do not wind up on land; most die far offshore and sink deep to become novel ecological zones known as whale falls. Some species that wash ashore are scientifically dolphins, i.e. members of the family Delphinidae, but for ease of use, this article treats them all as "drift whales". For example, one species notorious for mass strandings is the pilot whale, also known as "blackfish", which is taxonomically a dolphin.

.jpg.webp)

In historical sources, it is not always clear whether a given cetacean washed up alive or dead, but the term "drift whale" focuses on the benefits of its carcass – meat, blubber, fat, and other products – to the people who claimed it.[1] Nowadays, when a dead whale washes up on a beach, often the authorities are required to dispose of it as a potential hazard to human health, so the resource implications go the other way: a drift whale is no longer a benefit to a community, but an expensive disadvantage.[2]

Overview

Species

Many cetacean species have been documented as drift whales, but some are more common than others. In New England, for example, the carcasses of fin, humpback, sperm, right, and pilot whales, as well as dolphins, are most likely to drift ashore.[3] Some species have a naturally high buoyancy, and float when they are dead, aided by the gases of putrefaction.[4]

Whales that live in the pelagic ocean, far from the continental shelf, are less likely to wash up ashore than coastal species.[5] Once these deep-sea animals do find themselves in shallower waters, however, they may run into difficulties, as the gradual shelving of the shoreline is thought to play a role in confusing their sense of echolocation.[6] Sperm whale strandings are known to have occurred in the North Sea for centuries, and the incidents may be increasing with louder ship noise.[6]

Reasons

Aside from the whaling industry, most cetaceans have no predators other than the orca (killer whale)[7] and certain large sharks (such as the dusky[8]), which in both cases tend to attack in groups and focus on one young whale. Some drift whale carcasses show injuries consistent with attacks from these species, or, in modern times, with ship strikes (e.g., trauma from a propeller).[9][10] Another obvious and visible cause of traumatic death is cetacean bycatch, i.e., entanglement with fishing gear, which kills tens of thousands each year, according to the International Whaling Commission.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Other carcasses show no visible injury, and theories about why the animals died include the possibilities discussed for live strandings (especially active sonar) as well as illness and malnutrition.[12] Sometimes a necroscopy is performed, which can reveal the cause of death, such as ingestion of plastic pollution and other Marine debris.[13]

Locations

_(14732443556).jpg.webp)

Certain beaches are well known as likely spots for whales, and other gifts from the sea, to wash up: drift seeds, driftwood, and latterly sea glass and even messages in bottles. Modern recreational beachcombers use knowledge of how storms, geography, ocean currents, and seasonal events determine the arrival and exposure of rare finds;[14][15] the same applies to those looking out for drift whales.

Eponymous coastal features include Drift Whale Bay within Brooks Peninsula Provincial Park on the Pacific Coast of Vancouver Island.[16][17] Saint-Clément-des-Baleines on the Atlantic coast of France is named after its stranding beach.

Scavenging versus hunting

People have been using drift whales for millennia, long before the beginning of active whaling.[18] However, in relying on the archaeological record, the distinction between first scavenging and then hunting is not clear-cut.[19][20]

Whales as windfall

A whale's massive carcass would provide a coastal community with considerable amounts of meat and fat, without the danger and effort of venturing onto the open ocean to harpoon a living leviathan.[21] An additional resource, in the treeless Arctic, was the long bones, useful for construction. An even more specialised benefit is the occasional presence of ambergris in the guts of sperm whales; in 2021 a group of Yemeni fishermen sold their find for $1.5 million.[22] Blubber used to be processed into whale oil.[1] More generally, whale meat is still valued in some countries; muktuk (skin and blubber) is eaten uncooked as a delicacy in the Arctic, as fat is especially welcome in very cold climates.

The bounty and good fortune inherent in this find are recognised in etymology: "The meaning of the word 'drift-whale' in Icelandic, 'hvalreki,' has the same meaning as 'wind-fall' – an unexpected good incurred at no cost", according to Sigrún Davíðsdóttir, London correspondent of the Icelandic national broadcaster RÚV.[23] Two anthropologists, Thomas Talbot Waterman and Alfred Louis Kroeber, who worked with Yurok informants in California, classified drift whales as a gathered resource, rather than a product of hunting, as those beneficiaries ran no risk.[24]

Pre-contact aboriginal

Coastal people around the world came up with a technique called dolphin drive hunting, which exploits the animals' tendency to beach themselves. This sort of hunt, which depends on substantial community co-operation, still continues in a few places, as far apart as the North Atlantic (Whaling in the Faroe Islands), the South Pacific (Malaita dolphin drive hunt), and Japan (Taiji dolphin drive hunt).

It is harder to find evidence, archaeological or ethnographic, of North American indigenous people hunting large whales before cultural contact with Europeans, according to scholars of the Atlantic[25] and Pacific[20] coasts.

From scavenging to hunting

The skills learned from processing drift whales, such as flensing (stripping the blubber), may have led to seeking out live ones. For example, the Makah of Washington State have been hunting gray whales for at least 1500 years, but were harvesting stranded whales for many centuries before that.[26] On the other side of North America, drift whale scavenging on the Outer Banks of North Carolina led to organised hunts, documented at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum.[27]

When the early settlers arrived in New England, they saw from the deck of the Mayflower a huge number of whales, far more than they were accustomed to see in European waters, according to American historian W. Jeffrey Bolster.[25]

.jpg.webp)

March 1644, in Southampton, Long Island, saw the first recorded attempt of the New England colonists "to organize community efforts to hunt drift whales.”[28] The Native Americans had developed the technique of herding pilot whales onto the shelving beaches for slaughter; the colonists observed this, practised flensing the carcasses and rendering the blubber, improved on their weapons and boats, and then progressed to hunting on the ocean.[19] This early drift whaling at Southampton led gradually to the nearby Sag Harbor whaling fleet becoming the biggest in New York State, according to a curator at the local whaling museum.[29]

Tribes in Nantucket guarded and traded as sachem their ownership of drift whales assiduously. They were able to use their ownership and early treaties as a way to avoid royal taxes on the products.[30]

Both scavenging and hunting

Some communities both hunted and scavenged. William Barr, the Arctic historian, gives two examples of the late eighteenth century: the Moravian missions on Labrador, and possibly the Inuit of Hudson Strait, who had a trading relationship with the supply ships of the Hudson's Bay Company. However, Barr assumes that the drift whales were ones that the Inuit hunters (or possibly the European whaling ships) had harpooned and wounded, and the carcasses had come ashore some time later.[31]

Risks

Wrapped in a thick blanket of blubber, the carcass retains its mammalian heat, and the process of decomposition takes place relatively quickly; once ashore, there is a risk of the swollen whale exploding. That is a rare event, but more commonly, the build-up of pressure inside the abdominal cavity can lead to the extrusion of the whale's penis through the genital slit. A similar phenomenon, postmortem fetal extrusion, can occur to the carcass of a pregnant whale: Tim Flannery wrote that "A rotting whale could fill with gas to bursting, ejecting a fetus the size of a motor vehicle with sufficient force to kill a man."[32]

Consumption of drift whale carcasses, particularly if they have been dead for a long time, carries risks of food poisoning or worse. In 2002, fourteen residents of a Bering Sea fishing village ate muktuk (skin and blubber) from a beluga whale which they "estimated had been dead for at least several weeks", resulting in eight of them developing botulism, with two of the affected requiring mechanical ventilation. The Centers for Disease Control recommended boiling Alaska Native dishes to rid them of the botulism toxin.[33]

Mythology and ritual

Drift whales are a feature of fables and mythology. For example, William of Barkley Sound on Vancouver Island recounted tales to Edward Sapir, which were re-told by Kathryn Anne Bridge in a compendium about the Huu-ay-aht First Nations.[34]

The chiefs of certain West Coast peoples built private sacred places, called whalers' washing houses, where they could ritually purify themselves. The spiritual preparation that they undertook was not only for skill in the chase of living whales, but also to attract drift whales to their beach. The good fortune of the chief was understood to be tied to the spirit world, and the remains of human ancestors - especially the skulls - were used to ask for "whaling magic". The best known of these is the Yuquot Whalers Shrine, associated with the great Mowachaht chief Maquinna.[35]

The neighbouring Nuu-chah-nulth and Makah peoples used similar shrines to pull drift whales to them.[36]

Food resource

R. Lee Lyman proposed that drift whales might have formed a considerable summer food resource for people living on the coast of what is now Oregon, before contact with Europeans.[21][37]

Rights

Peoples that value whale meat and blubber have kept an eye out for drift whales, and traded the rights to them, for example bartering access to inland fishing rivers.[21] Specific people may have hereditary rights to drift whales and a particular locale.[34]

See also

References

- McMillan, Alan (Autumn 2015). "Whales and whalers in Nuu-Chah-Nulth Archaeology". BC Studies (187): 229–261. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Whaling Masters (1938), p. 10.

- "Why black whales are called "right whales"". New Bedford Whaling Museum Blog. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Why Scientists Drag Dead Whales to the Bottom of the Sea". Atlas Obscura. 21 April 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Ignace, Dianne; Beach, Katie. "Sperm whale drifts on Hesquiaht Beach". www.tofinotime.com. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Why, Who, What (2016). "Why do sperm whales wash up on beaches?". BBC News. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Reeves, Randall R.; Berger, Joel; Clapham, Phillip J. (2007). "Killer Whales as Predators of Large Baleen Whales and Sperm Whales". In James Estes (ed.). Whales, Whaling, and Ocean Ecosystems. doi:10.1525/california/9780520248847.003.0014. ISBN 9780520248847. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Sharks seen hunting and killing a whale for the first time". New Scientist. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Virginia Morell (23 July 2014). "Blue whales being struck by ships". Science. AAAS. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Ship Strikes: collisions between whales and vessels". International Whaling Commission. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- "Whale Entanglement – Building a Global Response". International Whaling Commission. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Mayton, Joseph (16 May 2015). "Why are so many whales dying on California's shores?". the Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (18 March 2019). "Dead whale washed up in Philippines had 40kg of plastic bags in its stomach". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- LamMotte, Richard (2004). Pure Sea Glass. Sea Glass Publishing. p. 20.

- Robinson, Chuck; Robinson, Debbie (1995). The Art of Shelling. Old Squan Village Publishing. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780964726765.

- "#1 – Drift Whale Bay". www.geonames.org. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Drift Whale Bay". knowbc.com. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Speller, Camilla; Hurk, Youri van den; Charpentier, Anne; Rodrigues, Ana; Gardeisen, Armelle; Wilkens, Barbara; McGrath, Krista; Rowsell, Keri; Spindler, Luke; Collins, Matthew; Hofreiter, Michael (5 September 2016). "Barcoding the largest animals on Earth: ongoing challenges and molecular solutions in the taxonomic identification of ancient cetaceans". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 371 (1702): 20150332. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0332. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4971184. PMID 27481784.

- Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration of Massachusetts (1938). Whaling Masters. Old Dartmouth Historical Society. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- McMillan, Alan (Autumn 2015). "Whales and whalers in Nuu-Chah-Nulth Archaeology". BC Studies (187): 227. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Bridge, Kathryn; Neary, Kevin (2013). Voices of the elders: Huu-ay-aht histories and legends. Victoria Vancouver Calgary: Heritage. p. 53. ISBN 978-1927051948.

- "'We found a fortune in the belly of a whale'". BBC News. BBC. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Davíðsdóttir, Sigrún. "Icelandic whaling is a relic of a past some (but ever fewer) Icelanders cannot let go of". Sigrún Davíðsdóttir's Icelog. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Thomas Talbot Waterman; Alfred Louis Kroeber (1943). Yurok Marriages, Volume 35. University of California Press. p. 84. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Bolster, W. Jeffrey (2014). Mortal sea : fishing the atlantic in the age of sail. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780674283961. OCLC 876287016.

- Renker, Ann M. (March 2002). Whale Hunting and the Makah Tribe: A Need Assessment (PDF). NOAA. p. 1. Retrieved 11 May 2018 – via NOAA Fisheries Service | West Coast Region.

- "Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum | Where Were the Whalers? The History and Archaeology of Whaling in North Carolina". outerbanks THISWEEK.com. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Yankee Whaling". New Bedford Whaling Museum. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- "A Brief History of the Sag Harbor Whaling Fleet". Southampton Historical Museum. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Chilton, Elizabeth S.; Rainey, Mary Lynne, eds. (29 February 2012). Nantucket and Other Native Places: The Legacy of Elizabeth Alden Little. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 68–71. ISBN 9781438432557.

- Barr, William (September 1994). "The Eighteenth Century Trade between the Ships of the Hudson's Bay Company and the Hudson Strait Inuit". Arctic. 47 (3): 236–246. doi:10.14430/arctic1294.

- Flannery, Tim (9 February 2012). "On the Minds of the Whales". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Middaugh J, Lynn T, Funk B, Jilly B, Maslanka S, McLaughlin J (17 January 2003). "Outbreak of Botulism Type E Associated with Eating a Beached Whale --- Western Alaska, July 2002". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. CDC. 52 (2): 24–26. PMID 12608715.

- Bridge, Kathryn (2004). Extraordinary accounts of Native life on the West Coast: words from Huu-ay-aht ancestors. Canmore, Alta.: Altitude Pub. Canada. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-1551537917.

Chief Si'xpa'tskwin of Cape Beale was always trying to better himself as a whaler. … [seeing a] drift whale … floating on the sea. … They manoevered the canoe close … [and] were extremely tired and stopped paddling. … How would they ever have the strength to drag the carcass to shore?

- Aldona Jonaitis (1999). The Yuquot whalers' shrine. Research contributions by Richard Inglis. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295978284. OCLC 247081771.

- Charlotte Coté (2010). Spirits of our whaling ancestors : revitalizing Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth traditions. Foreword by Micah McCarty (1st ed.). Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295990460. OCLC 1012176487.

- R. Lee Lyman (1991). Prehistory of the Oregon coast : the effects of excavation strategies and assemblage size on archaeological inquiry. Contributions by Ann C. Bennett, Virginia M. Betz, Linda A. Clark. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0124604155. OCLC 961208735.