Crime in Brazil

Crime in Brazil involves an elevated incidence of violent and non-violent crimes.[1] Brazil's homicide rate was 27.4 per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).[2] Brazil has the highest number of intentional homicides in the world, with 57,358 in 2018, or possibly second to Nigeria, which lacks accurate data but was estimated at 64,201 in 2016. In recent years, the homicide rate in Brazil has begun to decline. The homicide rate was 20.64 per 100,000 in 2020 with 43,879 killings, similar to 2019, but down from 30.67 per 100,000 in 2017.[3]

Brazil is a central hub for the Illegal drug trade.[4]

Homicides

In terms of absolute number of murders in a year, Brazil has the most murders of any country by total number (62,318) followed by India (29,000), the USA (25,000) and Mexico (24,576).

In 2018, Brazil had a murder rate of 24.7 per 100,000 people. In 2017, Brazil had a murder rate of 29.2 per 100,000 population.[5][6] There were a total of 56,101 murders in Brazil in 2017.[5] Another study has the 2017 murder rate at 32.4 per 100,000, with 64,357 homicides.[7] In 2016, Brazil had a record 61,819 murders or on average 168 murders per day, giving a yearly homicide rate of 29.9 per 100,000 population.[8]

In 2017, Brazil had a record number of murders, with homicides rising 4.20% with 63,880 homicides.[9][10]

In 2019, the anti-violence NGO Rio de Paz stated that only 8% of homicides in Brazil lead to criminal convictions.[11]

By Brazilian states

List of the Brazilian state capitals by homicide rate (homicides per 100,000):[12]

| Capital/Region | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern (state capitals) | 31.9 | 39.5 | 31.3 | 34.2 | 32.1 | 34.2 | 34.4 | 31.8 | 35.6 | 34.9 | 33.0 | |

| Belém (PA) | 24.5 | 29.1 | 15.1 | 25.9 | 27.0 | 31.8 | 34.7 | 29.6 | 44.7 | 33.9 | 34.2 | |

| Boa Vista (RR) | 34.6 | 51.5 | 51.4 | 40.4 | 32.1 | 38.2 | 33.0 | 21.5 | 23.1 | 220 | 25.7 | |

| Macapá (AP) | 46.6 | 51.0 | 64.1 | 46.2 | 44.3 | 44.0 | 44.1 | 38.5 | 38.0 | 35.8 | 32.3 | |

| Manaus (AM) | 35.3 | 40.7 | 35.3 | 33.0 | 25.2 | 26.5 | 29.3 | 26.2 | 29.4 | 32.3 | 32.5 | |

| Palmas (TO) | 70.0 | 12.7 | 19.7 | 21.8 | 26.5 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 21.3 | 13.0 | 13.6 | 12.8 | |

| Porto Velho (RO) | 38.3 | 70.3 | 55.5 | 61.0 | 66.9 | 63.2 | 51.1 | 71.4 | 56.4 | 68.5 | 51.3 | |

| Rio Branco (AC) | 36.6 | 38.4 | 17.0 | 36.4 | 39.0 | 44.8 | 37.9 | 30.9 | 23.9 | 36.3 | 30.1 | |

| Northeast (state capitals) | 40.8 | 33.6 | 30.2 | 34.0 | 39.5 | 39.4 | 41.7 | 40.8 | 44.8 | 49.6 | 52.4 | |

| Aracaju (SE) | 19.3 | 16.8 | 35.2 | 39.9 | 60.9 | 54.4 | 50.6 | 47.2 | 40.5 | 46.7 | 38.9 | |

| Fortaleza (CE) | 27.0 | 20.3 | 25.2 | 28.2 | 27.9 | 31.8 | 29.5 | 28.5 | 34.0 | 35.0 | 40.3 | |

| João Pessoa (PB) | 33.3 | 38.4 | 36.0 | 37.8 | 41.3 | 42.5 | 44.7 | 42.6 | 48.1 | 48.7 | 56.6 | |

| Maceió (AL) | 38.4 | 33.3 | 30.9 | 45.1 | 59.3 | 61.3 | 61.2 | 64.5 | 68.6 | 98.0 | 97.4 | |

| Natal (RN) | 18.1 | 16.2 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 15.6 | 13.9 | 23.0 | 13.2 | 18.5 | 20.5 | 28.3 | |

| Recife (PE) | 105.3 | 114.0 | 99.3 | 97.5 | 97.2 | 90.5 | 91.4 | 91.8 | 88.2 | 90.7 | 87.5 | |

| Salvador (BA) | 41.6 | 15.4 | 7.9 | 12.9 | 21.3 | 23.2 | 28.6 | 28.5 | 39.7 | 43.7 | 49.3 | |

| São Luís (MA) | 22.2 | 16.5 | 12.8 | 16.6 | 27.4 | 21.4 | 30.8 | 32.6 | 30.0 | 31.4 | 38.4 | |

| Teresina (PI) | 16.9 | 17.6 | 14.0 | 22.2 | 23.2 | 27.8 | 28.5 | 26.0 | 29.4 | 33.5 | 28.2 | |

| Southeast (state capitals) | 56.0 | 58.0 | 59.8 | 58.9 | 58.0 | 55.0 | 54.5 | 47.5 | 36.5 | 34.5 | 27.8 | |

| Belo Horizonte (MG) | 20.7 | 25.0 | 26.8 | 34.8 | 35.0 | 42.9 | 57.6 | 64.7 | 54.4 | 49.9 | 49.5 | |

| Rio de Janeiro (RJ) | 65.8 | 62.6 | 53.5 | 56.6 | 55.5 | 62.8 | 56.1 | 52.8 | 41.9 | 46.4 | 35.7 | |

| São Paulo (SP) | 56.7 | 61.1 | 69.1 | 64.8 | 63.5 | 52.6 | 52.4 | 39.8 | 28.3 | 23.2 | 17.4 | |

| Vitória (ES) | 103.5 | 106.6 | 108.3 | 79.0 | 85.1 | 80.2 | 73.0 | 82.7 | 83.9 | 86.1 | 75.4 | |

| Southern (state capitals) | 29.5 | 25.1 | 27.3 | 29.9 | 30.3 | 34.8 | 35.5 | 39.3 | 40.4 | 40.3 | 43.3 | |

| Curitiba (PR) | 26.6 | 22.7 | 25.9 | 26.2 | 28.0 | 32.2 | 36.6 | 40.8 | 44.3 | 48.9 | 45.5 | |

| Florianópolis (SC) | 9.4 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 17.0 | 24.7 | 27.1 | 28.9 | 24.4 | 19.4 | 19.5 | |

| Porto Alegre (RS) | 37.2 | 31.4 | 32.9 | 39.2 | 36.5 | 40.5 | 36.4 | 40.3 | 40.1 | 35.5 | 47.3 | |

| Central-West (state capitals) | 35.3 | 37.7 | 37.6 | 39.2 | 39.1 | 37.4 | 39.3 | 36.8 | 33.4 | 33.4 | 34.1 | |

| Brasília (DF) | 35.6 | 37.4 | 36.7 | 37.5 | 36.9 | 34.7 | 39.1 | 36.5 | 31.9 | 32.3 | 33.5 | |

| Campo Grande (MS) | 41.9 | 36.4 | 30.8 | 39.3 | 34.0 | 34.5 | 35.3 | 30.7 | 28.5 | 27.1 | 32.2 | |

| Cuiabá (MT) | 55.3 | 76.0 | 68.5 | 69.5 | 76.9 | 52.0 | 49.8 | 45.5 | 44.4 | 40.7 | 38.8 | |

| Goiânia (GO) | 22.1 | 22.6 | 30.1 | 28.6 | 29.4 | 38.1 | 37.4 | 37.4 | 34.6 | 36.4 | 34.6 | |

| 45.7 | 45.3 | 44.6 | 45.8 | 46.5 | 45.5 | 46.1 | 42.4 | 38.5 | 38.7 | 36.6 |

Murders increased during the late-2000s. Bucking this trend are the two largest cities. In 2008 Rio de Janeiro registered the lowest murder rate in 18 years, while São Paulo is now approaching the 10 murders per 100,000 mark, down from 35.7 in 1999. A notable example is the municipality of Diadema, where crime rates fell abruptly.

Total murders set new records in the three years from 2009 to 2011, surpassing the previous record set in 2003. 2003 still holds the record for murders per 100,000 in Brazil; that year alone the rate was 28.9.[13] Police records post significantly lower numbers than the health ministry.

Seven out of the twenty most violent cities in the world are in Brazil due to a rise in street violence.[14] In descending order as of April 2018, they are: Natal (fourth highest homicide rate worldwide), Fortaleza (seventh), Belém (tenth), Vitória da Conquista (eleventh), Maceió (fourteenth), Aracaju (eighteenth), and Feira de Santana (nineteenth).[15]

Robbery

Carjacking is common, particularly in major cities. Local citizens and visitors alike are often targeted by criminals, especially during public festivals such as the Carnaval.[16] Pickpocketing and bag snatching are common. Thieves operate in outdoor markets, in hotels and on public transport.

A trending crime known as "arrastões" (dragnets) occur when many perpetrators act together, simultaneously mug pedestrians, sunbathers, shopping mall patrons, and/or vehicle occupants stuck in traffic. Arrastões and random robberies may occur during big events (Carnaval), soccer games, or during peak beach hours.[17]

Kidnapping

Express kidnappings, where people are abducted while withdrawing funds from ATM, are common in major cities including Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Brasília, Curitiba, Porto Alegre, Salvador and Recife.[18]

Corruption

Corruption in Brazil is a pervasive social problem. Brazil scored 38 on the 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index, tying with India and Bosnia and Herzegovina, being ranked 76th among 175 countries.[19] Corruption was cited among many issues that provoked the 2013 protests in Brazil.[20] Embezzlement and corruption have influenced Brazilian elections for decades; however, the electorate continues to vote, whether out of preference or lack of choice, for candidates who have been accused, and in some instances convicted, on charges of corruption.[21]

Domestic violence

Between 10 and 15 women are murdered each day in Brazil.[22][23] A government sponsored study found that 41,532 women were murdered in Brazil between 1997 and 2007.[23] In 2012, 8% of all homicide victims were female. However, this is still far below the male victimization rate, in which men constitute 92% of homicide victims in Brazil as of 2012.[24]

Crime dynamics

Prevention and drug war

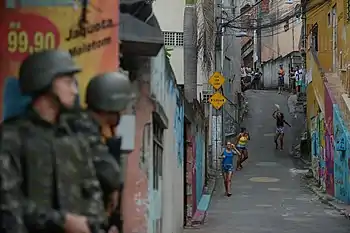

| Brazilian drug war | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Brazilian Army soldiers in a street in Vitória | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Primeiro Comando da Capital Comando Vermelho Terceiro Comando | Brazilian police militias | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| More than 44,000 deaths[25][26][27][28][29][30] | ||||||||

A program to combat gangs and gang centered violence, the 'Pacifying Police Units' (UPP), was introduced in the traditionally violent favelas of Rio de Janeiro in 2008/2009. UPP personnel are well-educated and trained in both human rights and modern police techniques; their aim is to supplant the community presence of gangs as central community figures. In 2013, 34 UPP units operated in 226 different communities, with a reach of 1.5 million citizens.[31]

The UPP program symbolizes a new crime prevention paradigm that focuses on social inclusion and community development. However, in some areas the homicide rate was already dropping prior to the implementation of the program. Therefore, the drop in crime may be due to a general trend of decline in homicides as well.[5]

According to Instituto de Segurança Pública (ISP) data, between 2007 (the year before the first UPP) and 2013, the violent death rate in areas with UPPs dropped by 80% – a much more pronounced reduction than in the rest of the municipality, which also experienced a drop in these indices over the period. The homicide rate caused by opposition to police intervention was the indicator of violence that showed the most significant reduction, of almost 90%, but also decreased other crimes against life and property.[32]

In 2014, however, the violent lethality indicators rose again not only in the UPP areas, but in the entire municipality. Rio had not seen so many violent deaths since 2009, the first year of the UPPs. Today the numbers are practically the same as in the pre-UPP period.

In the latest survey by the Cândido Mendes University Center for Security and Citizenship Studies (Cesec), carried out in 2014 with UPP officers, researchers had already found a complete abandonment of the "proximity" approach and the return to repressive policing.[32] According to them, the "lack of command, control and logistics" is the cause of all the problems in the Pacifying Police Units, including the death of police officers in the communities.[33]

As of 2015, Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) of Rio de Janeiro are no longer useful, according to specialists. After more than ten years of design, they are now beginning to undergo drastic changes, since police officers from different units also began to patrol the streets, in addition to the usual policing. The lack of formalization of the program and the establishment of evaluation indicators was also a problem, say the researchers. The UPPs have never had an internal and systematic evaluation.[32]

The movement was expanded "hastily", in an "unbridled" way. Between 2010 and 2013, the number of UPPs almost tripled, jumping from 13 to 36. The exaggerated expansion also ended up overloading the Military Police, an institution that, according to Rodrigues, a former Military Police Colonel, already needed (and still needs) structural reforms.[32] "The solution is beyond the police. It seems a cliché, but the social part has been missing since the beginning of the project", evaluated the former Commander of the Military Police between 2007 and 2008.[33]

In the 7 years of the project, there were several allegations of corruption and abuse of force involving UPP soldiers. The most remembered among them is the torture and death of the bricklayer Amarildo de Souza.

The proposal, however, proved to be flawed due to the inexperience of these new military police officers with no apparent condition to work in former faction strongholds, as was the case in Rocinha and Complexo do Alemão. Burning containers, lack of restrooms and armor, accumulated garbage, broken air conditioning was just one of the proofs that the military police were not working under ideal conditions. And on at least eight bases the PMs would be working in an extreme situation.[32] Former ISP Director Ana Paula Miranda also believes that "during all this time, an idea was made that the problems in Rio de Janeiro were over", "That was the first mistake. Excessive advertising not taking into account the flaws throughout the project".[34]

Since the first UPP arrived, in the Santa Marta community, in Botafogo, in 2008, the reality of the residents has changed not only in relation to the actions of armed groups. Everything got more expensive: the electricity bill started to arrive and there was no way to practice these "thefts" in electricity. By 2015, the favela that had once a "model" UPP unit, saw the number of homicides spike, alongside the drug war.[34][35]

In the past, the State of Rio de Janeiro had already carried out a similar attempt at occupation, and for the same reasons, in Ana Paula's opinion, the project did not succeed and, it seems, the lesson was not learned. "The strategy is very similar. There was a lack of perception that these problems would all happen later".[34]

In April 2017, at Complexo do Alemão, a 19.6-foot-high (6.0 m) armored tower was installed, resistant to rifles and grenade explosions, to house UPP police from the Nova Brasília community.[32]

As of May 2021, a new project was released by the then Governor Cláudio Castro and documents obtained by the media in September showed the discussion of the project for at least 2 months. Called Cidade Integrada (Integrated City), the new program for the occupation of communities by the Government of Rio de Janeiro, in a model of public security and urban and social interventions. It is not yet clear, however, how the police will act in this new project.[36][37]

Jacarezinho, where there is strong influence from drug trafficking, and Muzema, controlled by the militia, are expected to be the first to receive the program, with its launch scheduled for late November or early December.

Gangs

Gang violence has been directed at police, security officials and related facilities. Gangs have also attacked official buildings and set alight public buses.[38] May 2006 São Paulo violence began on the night of 12 May 2006 in São Paulo, Brazil. It was the worst outbreak of violence recorded in Brazilian history and was directed against security forces and some civilian targets. By 14 May the attacks had spread to other Brazilian states including Paraná, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais and Bahia. Another outbreak of violence took place in São Paulo in July 2006.

2016 saw a new string of deadly prison riots. The nature of these riots was a turf war between the Primeiro Comando da Capital and other gangs, with the PCC aggressively expanding its territory.[39][40] In 2019, a prison riot between two gangs, Comando Vermelho and Comando Classe A, left 57 dead after hours of fighting.[41]

Brazilian gang members have used children to commit crimes because their prison sentences are shorter. As of 2007, murder was the most common cause of death among youth in Brazil, with 40% of all murder victims aged between 15 and 25 years old.[42]

In regard to inter-gang conflict, gangs typically challenge or demand an aggressive reaction to defend their reputations. If someone does not respond in this manner, they are socially isolated. The gangs in Brazil are very territorial, and focused on their illegal business. Theft and robbery bring in small amounts of money compared to narcotic and weapons sales so it is less common for these gangs to get involved in petty crimes of theft or robbery.[43]

The gangs in Rio de Janeiro are interested in harmony because they do not want any contact with the police. They will help others in the community, with money and even protection, just to be sure that the police do not come around. Children and other members of the community see notably rich and powerful gang members and want to emulate this behavior. Gang members then become a substitute for family and are role models because they have respect and money.[43]

It is most common for these gangs to be under a military command structure.[43] Each Rio favela has one dono who controls the managers of a favela and the soldados in his territory. The latter protect the favela against other drug factions and the police. They are also responsible for taking over other favelas. The managers of a favela control the managers of the bocas (the places where drugs are sold in the favela). The managers of the bocas in turn control the drug dealers who sell the drugs in the area around a boca. There are children and women who wait at the entrances to a favela to signal to the others if the police or other gangs are about to enter.[43] It is normal to join at about 10 years old, and by 12 years old to carry weapons. These gangs are attractive to the children and youth because they offer protection, recognition, and career options that those who join could not achieve on their own. Favelas are now often controlled by juveniles and young adults.[43]

The concern here is of the strong ties that are between illegal business and politicians, police officers, the justice system, and the economy. Not all people are involved but all layers of society are affected because of corruption. Police are bribed to not disturb what these gangs are doing, and many of them are dealers themselves.[43] Also, young children carry guns and may be nervous, aware of peer pressure, or on drugs, and can become careless. Brutality and homicide rates have skyrocketed in countries with younger gang members like this.[43]

Drug trafficking

Drug trafficking makes up for an increasingly large portion of crime in Brazil. A total of 27% of all incarcerations in Brazil are the result of drug trafficking charges. Between 2007 and 2012 the number of drug related incarcerations has increased from 60.000 to 134.000; a 123 percent increase.[32]

The primary drug trafficking jobs for children and youth are:

- endoladores: packages the drugs[43]

- olheiro(a) and/or fogueteiro(a): lookouts to provide early warning of police or any enemy drug faction invasion[43]

- Drug mule: carries drugs to others inside their body, these are unwilling members of a gang, and don't survive for very long.

- vapor: drug sales persons[43]

- gerente da boca: overseer of drug sales[43]

- soldado(a): soldiers, armed and employed to maintain protection[43]

- fiel: personal armed security guard for the "gerente geral"[43]

- gerente geral or dono: owner/boss[43]

- Aviões (literally translated to "little airplanes"). These are the children who deliver messages and drugs to customers. They are not described in the hierarchal organization, but they are very low/entry-level positions. In addition, those I. this position have the most arrests.[43]

Of 325 incarcerated youth, 44% of boys and 53% of girls reported some involvement with drug trafficking.[43] Selling and carrying drugs were the most common activities between both boys and girls. The most common drug was marijuana, followed by cocaine and crack.[43] From the study; 74% had used marijuana, 36% had snorted cocaine, and 21% had used crack.[43]

Youth held low positions in the hierarchy and engaged in relatively low volumes of activity for short periods of time, but 51% of youth involved with trafficking reported it to be very easy to obtain a gun,[43] while 58% involved in trafficking reported it to be very easy to obtain cocaine.[43]

On 6 May 2021, at least 25 people were killed in a shootout between police and a drug-dealing gang.

Penalties

Criminal penalties for youths, who make up a significant portion of street crime, is internment in educational centers with a maximum stay of 3 years.[44] Youths are not punished under the penal code, but under the Brazilian Statute of the Child and Adolescent.[44]

For adults, the consumption of drugs is nearly decriminalized, but activities in any way related to the sale of drugs are illegal.[45] The distinction between drug consumers and suppliers is poorly defined and thus controversial. This ambiguity gives judges a high degree of discretion in sentencing, and leads to accusations of discriminatory or unequal court rulings.[46] Drug consumers receive light penalties varying from mandatory self-education on the effects of drugs to community service. The minimum sentence for a drug supplying offense is 5 to 15 years in prison.[47] Critics of the consumer/supplier distinction between offenses argue for a more complex categorization than only two categories, to allow for more lenient punishments for minor drugs violations.[48] Former UN secretary general Kofi Annan and former president of Brazil Cardoso[49] argue for stepping away from the "war" approach on drugs, saying the militant approach can be counterproductive.[47] However, many others hold a hard-line preference for heavy penalization.[45]

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Brazil 2016 Crime & Safety Report: Recife. Overseas Security Advisory Council.

This article incorporates public domain material from Brazil 2016 Crime & Safety Report: Recife. Overseas Security Advisory Council.

- "Brazil-Crime". Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "UNODC Statistics Online". data.unodc.org. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "DATAUNODC". Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- "The World Factbook". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "UNODC: Global Study on Homicide". Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "Murder Rates By Country". Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Staff, John Zarocostas-McClatchy Foreign. "As world homicide rate declines, killings rise in Latin America, Caribbean". Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- "Brazil Had Record of 168 Murders per Day in 2016". Latin American Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Brazil suffers record murder tally in 2017, ahead of election". Reuters. 9 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "A most violent year: Brazil murder toll hits record 63,800". The Week. 10 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "NGO: 92 Pct. of murders in Brazil go unpunished". EFE. 13 March 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "Mapa da Violência 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- "O DIA Online – Rio no mapa da morte". Archived from the original on 11 May 2011.

- "Jair Bolsonaro, Latin America's latest menace". The Economist. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "The Most Dangerous Cities in the World". WorldAtlas. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Violence mars Rio carnival dawn". BBC News. 28 February 2003. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "Reports". Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Canada, Gouvernement du Canada, Affaires étrangères et Commerce international. "Erreur 404 – Voyage.gc.ca". Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - e.V., Transparency International (3 December 2014). "How corrupt is your country?". Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- phillipviana 14 June 2013 What's REALLY behind the Brazilian riots? Archived 23 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine CNN

- Welle, Deutsche Welle. "The persistence of corruption in Brazilian politics – Americas – DW.COM – 05.10.2014". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "Brazil femicide law signed by President Rousseff". BBC News. 10 March 2015. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- de Moura, Helena. "Study: In Brazil, 10 women killed daily in domestic violence". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- Watts, Jonathan (6 May 2015). "Latin America leads world on murder map, but key cities buck deadly trend". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "cresce numero de pessoas mortas pela policia no brasil assassinatos de policiais em 2016". caem.ghtml. 10 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- "com guerra de faccoes brasil atinge novo recorde de homicidios em 2017". noticias.uol.com.br. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- "cresce numero de pessoas mortas pela policia no brasil assassinatos de policiais em 2018". caem.ghtml. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- "cresce numero de pessoas mortas pela policia no brasil assassinatos de policiais em 2019". caem.ghtml. 16 April 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- "cresce numero de pessoas mortas pela policia no brasil assassinatos de policiais em 2020". caem.ghtml. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- "cresce numero de pessoas mortas pela policia no brasil assassinatos de policiais em 2021". caem.ghtml. 4 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- agt. "UNODC: Global Study on Homicide". Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "A falência das UPPs". Instituto Igarapé, Exame (in Brazilian Portuguese). 3 July 2017. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- "Polícia admite erros nas UPPs e especialistas avaliam mortes de PMs". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 11 July 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- "Os 10 erros da política de segurança das UPPs no Rio". Terra (in Portuguese). 22 March 2014. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- "Antes pacificado, Morro Dona Marta, no Rio, registra dois tiroteios por semana". G1 (in Portuguese). 27 September 2018. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- "Novo plano de ocupação social de favelas divide líderes comunitários e especialistas". O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 11 November 2021. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- "Cidade Integrada: novo projeto de ocupação de comunidades prevê início por Muzema e Jacarezinho". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 10 November 2021. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- "Gang violence grips Brazil state". BBC News. 15 May 2006. Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "56 killed, many beheaded, in grisly Brazil prison riot". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Brazil drug gangs spark prison riot, 56 dead". Reuters. 3 January 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Brazil jail riot leaves at least 57 dead". 30 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Glüsing, Jens (2 March 2007). "Violence in Rio de Janeiro: Child Soldiers in the Drug Wars". Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- McLennan, John D.; Bordin, Isabel; Bennett, Kathryn; Rigato, Fatima; Brinkerhoff, Merlin (2008). "Trafficking among youth in conflict with the law in Sao Paulo, Brazil". Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 43 (10): 816–823. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0365-6. PMID 18473132. S2CID 24462112.

- Zdun, Steffen (2008). "Violence in street culture: Cross-cultural comparison of youth groups and criminal gangs". New Directions for Youth Development. 2008 (119): 39–54. doi:10.1002/yd.272. PMID 18855319.

- "About drug law reform in Brazil". Transnational Institute. 30 June 2015. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Miraglia, Paul (2016). "Drugs and Drug Trafficking in Brazil: Trends and Policies" (PDF). Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence Latin America Initiative. 2016: 1–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018 – via Brookings Institution.

- "Decriminalization of Narcotics: Brazil". www.loc.gov. Soares, Eduardo. July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Garlick, Aloysius (4 April 2013). "Drug trafficking is a crime that most condemn in Brazil". talkingdrugs.org. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Newman, Tony. "Former UN Head Kofi Annan and Former President of Brazil Cardoso Call for Decriminalization of Drugs". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

.svg.png.webp)