Guyenne

Guyenne or Guienne (/ɡiˈjɛn/, French: [ɡɥijɛn]; Occitan: Guiana [ˈɡjanɔ]) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of Aquitania Secunda and the archdiocese of Bordeaux.

.jpg.webp)

The name "Guyenne" comes from Aguyenne, a popular transformation of Aquitania.[1] In the 12th century it formed, along with Gascony, the duchy of Aquitaine, which passed under the dominion of the kings of England by the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II.[2]

In the 13th century, through the conquests of Philip II, Louis VIII and Louis IX, Guyenne was confined within the narrower limits fixed by the treaty of Paris (1259) and became distinct from Aquitaine. Guyenne then comprised the Bordelais (the old countship of Bordeaux), the Bazadais, part of Périgord, Limousin, Quercy and Rouergue and the Agenais ceded by Philip III to Edward I in the treaty of Amiens (1279). Still united with Gascony, it formed a duchy extending from the Charentes to the Pyrenees. This duchy was held as a fief on the terms of homage to the French kings and, both in 1296 and 1324, it was confiscated by the kings of France on the ground that there had been a failure in the feudal duties.[2]

At the treaty of Brétigny (1360), King Edward III of England acquired the full sovereignty of the duchy of Guyenne, together with Aunis, Saintonge, Angoumois and Poitou. The victories of Bertrand du Guesclin and Gaston III, Count of Foix, restored the duchy soon after to its 13th-century limits. In 1451, it was conquered and finally united to the French crown by Charles VII. In 1469, Louis XI gave it in exchange for the territories of Champagne and Brie to his brother Charles, Duke of Berry, after whose death in 1472 it was again united to the royal domain.[2]

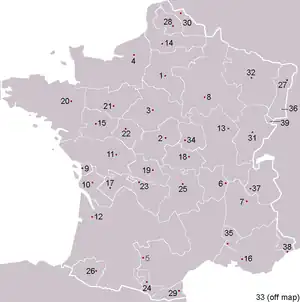

Guyenne then formed a government (gouvernement général) which from the 17th century onwards was united with Gascony.[2] In 1779, Louis XVI convened the provincial assemblies of Guyenne and considered expanding the assembly to other provinces, but abandoned this idea after experiencing the opposition of the privileged classes in Guyenne.[3] The government of Guyenne and Gascony (Guienne et Gascogne), with its capital at Bordeaux, lasted until the end of the Ancien Régime (1792). Under the French Revolution, the departments formed from Guyenne proper were those of Gironde, Lot-et-Garonne, Dordogne, Lot, Aveyron and the chief part of Tarn-et-Garonne.[2]

References

- Xavier de Planhol, An Historical Geography of France (Cambridge, 1994), p. 168.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Guienne". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Peter Kropotkin (1909). "Chapter 5". The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793. Translated by N. F. Dryhurst. New York: Vanguard Printings.

The weapon used by Louis XVI, in preference to all others was deceit. Only fear made him yield, and, using always the same weapons, deceit and hypocrisy, he resisted not only up to 1789, but even up to the last moment, to the very foot of tile scaffold. At any rate, in 1778, at a time when it was already evident to all minds of more or less perspicacity, as it was to Turgot and Necker, that the absolute power of the King had had its day, and that the hour had come for replacing it by some kind of national representation, Louis XVI could never be brought to make any but the feeblest concessions. He convened the provincial assemblies of the provinces of Berri and Haute-Guienne (1778 and 1779). But in face of the opposition shown by the privileged classes, the plan of extending these assemblies to the other provinces was abandoned, and Necker was dismissed in 1781.

Further reading

- Pépin, Guilhem (2006). "Les cris de guerre " Guyenne ! " et " Saint Georges ! "". Le Moyen Âge. 112 (2): 263–81. doi:10.3917/rma.122.0263.