Province of Alsace

The Province of Alsace (Province d'Alsace) was an administrative region of the Kingdom of France and one of the many provinces formed in the late 1600s. In 1648, the Landgraviate of Upper-Alsace was absorbed into the Kingdom of France and subsequently became the Province of Alsace, which it remain an integral part of for almost 150 years. In 1790, as a result of the Decree dividing France into departments, the province was disestablished and split into three departments: Bas-Rhin (Lower Rhine), Haut-Rhin (Upper Rhine), and part of Moselle.

| Province of Alsace Province d'Alsace | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1648–1790 | |||||||||||||

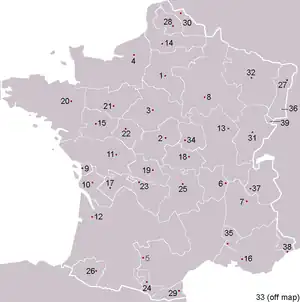

.svg.png.webp) Location of Alsace within the Kingdom of France in 1789 | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Strasbourg | ||||||||||||

| Demonym | Alsacien, Alsaciens, Alsacienne, Alsaciennes | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||

| • Type | Province | ||||||||||||

| King of France | |||||||||||||

• 1648–1715 | Louis XIV | ||||||||||||

• 1774–1790 | Louis XVI | ||||||||||||

| Governor General of Alsace | |||||||||||||

• 1788–1789 | Jacques Philippe, Marquis de Choiseul-Stainville | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early Modern | ||||||||||||

| 1648 | |||||||||||||

• Decree dividing France into departments | 1790 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

History

In 1469, following the Treaty of St. Omer, Upper Alsace was sold by Archduke Sigismund of Austria to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Although Charles was the nominal landlord, taxes were paid to Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor. The latter was able to use this tax and a dynastic marriage to his advantage to gain back full control of Upper Alsace (apart from the free towns, but including Belfort) in 1477 when it became part of the demesne of the Habsburg family, who were also rulers of the empire. The town of Mulhouse joined the Swiss Confederation in 1515, where it was to remain until 1798.

By the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, Strasbourg was a prosperous community, and its inhabitants accepted Protestantism in 1523. Martin Bucer was a prominent Protestant reformer in the region. His efforts were countered by the Roman Catholic Habsburgs who tried to eradicate heresy in Upper Alsace. As a result, Alsace was transformed into a mosaic of Catholic and Protestant territories. On the other hand, Mömpelgard (Montbéliard) to the southwest of Alsace, belonging to the Counts of Württemberg since 1397, remained a Protestant enclave in France until 1793.

This situation prevailed until 1639, when most of Alsace was conquered by France to keep it out of the hands of the Spanish Habsburgs, who by secret treaty in 1617 had gained a clear road to their valuable and rebellious possessions in the Spanish Netherlands, the Spanish Road. Beset by enemies and seeking to gain a free hand in Hungary, the Habsburgs sold their Sundgau territory (mostly in Upper Alsace) to France in 1646, which had occupied it, for the sum of 1.2 million Thalers. When hostilities were concluded in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia, most of Alsace was recognized as part of France, although some towns remained independent. The treaty stipulations regarding Alsace were complex. Although the French king gained sovereignty, existing rights and customs of the inhabitants were largely preserved. France continued to maintain its customs border along the Vosges mountains where it had been, leaving Alsace more economically oriented to neighbouring German-speaking lands. The German language remained in use in local administration, in schools, and at the (Lutheran) University of Strasbourg, which continued to draw students from other German-speaking lands. The 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau, by which the French king ordered the suppression of French Protestantism, was not applied in Alsace. France did endeavour to promote Catholicism. Strasbourg Cathedral, for example, which had been Lutheran from 1524 to 1681, was returned to the Catholic Church. However, compared to the rest of France, Alsace enjoyed a climate of religious tolerance.

France consolidated its hold with the 1679 Treaties of Nijmegen, which brought most remaining towns under its control. France seized Strasbourg in 1681 in an unprovoked action. These territorial changes were recognised in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick that ended the War of the Grand Alliance. But Alsace still contained islands of territory nominally under the sovereignty of German princes and an independent city-state at Mulhouse. These enclaves were established by law, prescription and international consensus.[1]

Government

Following the governmental reforms of 1773, the Province of Alsace formed part of the Government of Alsace (Gouvernement d'Alsace). The province itself was further divided into two 'regions': Lower Alsace (North) and Upper Alsace (South).[2]

Following the Decree dividing France into departments announced on 22 December 1789, the Province of Alsace was disestablished and formed the departments of Bas-Rhin (Lower Rhine), Haut-Rhin (Upper Rhine), and part of Moselle.

Culture

Alsace historically was part of the Holy Roman Empire and the German realm of culture. Since the 17th century, the region has passed between German and French control numerous times, resulting in a cultural blend. German traits remain in the more traditional, rural parts of the culture, such as the cuisine and architecture, whereas modern institutions are totally dominated by French culture.

Strasbourg

Strasbourg's arms are the colours of the shield of the Bishop of Strasbourg (a band of red on a white field, also considered an inversion of the arms of the diocese) at the end of a revolt of the burghers during the Middle Ages who took their independence from the teachings of the Bishop. It retains its power over the surrounding area.

Flags

There is controversy around the recognition of the Alsatian flag. The authentic historical flag is the Rot-un-Wiss; Red and White are commonly found on the coat of arms of Alsatian cities (Strasbourg, Mulhouse, Sélestat...)[3] and of many Swiss cities, especially in Basel's region. The German region Hesse uses a flag similar to the Rot-un-Wiss. As it underlines the Germanic roots of the region, it was replaced in 1949 by a new "Union jack-like" flag representing the union of the two départements. It has, however, no real historical relevance. It has been since replaced again by a slightly different one, also representing the two départements. With the purpose of "Francizing" the region, the Rot-un-Wiss has not been recognized by Paris. Some overzealous statesmen have called it a Nazi invention – while its origins date back to the 11th century and the Red and White banner[4] of Gérard de Lorraine (aka. d'Alsace). The Rot-un-Wiss flag is still known as the real historical emblem of the region by most of the population and the départements' parliaments and has been widely used during protests against the creation of a new "super-region" gathering Champagne-Ardennes, Lorraine and Alsace, namely on Colmar's statue of liberty.[5]

Language

Although German dialects were spoken in Alsace for most of its history, the dominant language in Alsace today is French.

The traditional language of the région is Alsatian, an Alemannic dialect of Upper German spoken on both sides of the Rhine and closely related to Swiss German. Some Frankish dialects of West Central German are also spoken in "Alsace Bossue" and in the extreme north of Alsace. Neither Alsatian nor the Frankish dialects have any form of official status, as is customary for regional languages in France, although both are now recognized as languages of France and can be chosen as subjects in lycées.

Although Alsace has been part of France multiple times in the past, the region had no direct connection with the French state for several centuries. From the end of the Roman Empire (5th century) to the French annexation (17th century), Alsace was politically part of the German world.

The towns of Alsace were the first to adopt the German language as their official language, instead of Latin, during the Lutheran Reform. It was in Strasbourg that German was first used for the liturgy. It was also in Strasbourg that the first German Bible was published in 1466.

Footnotes

- Doyle, William (1989). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-880493-2.

- "Alsace | History, Culture, Geography, & Map | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- "Unser LandBrève histoire d'un drapeau alsacien". Unser Land.

- Genealogie-bisval.net

- "Colmar : une statue de la Liberté en "Rot und Wiss"". France 3 Alsace. 16 November 2014.

Further reading

- Gerson, Daniel. Die Kehrseite der Emanzipation in Frankreich: Judenfeindschaft im Elsass 1778 bis 1848. Essen: Klartext, 2006. ISBN 3-89861-408-5.

- Kaeppelin, Charles E. R, and Mary L. Hendee. Alsace Throughout the Ages. Franklin, Pa: C. Miller, 1908.

- Lazer, Stephen A. State Formation in Early Modern Alsace, 1648–1789. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2019. Archived 2019-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Putnam, Ruth. Alsace and Lorraine: From Cæsar to Kaiser, 58 B.C.–1871 A.D. New York: 1915.