Dumfries

Dumfries (/dʌmˈfriːs/ ⓘ dum-FREESS; Scots: Dumfries; from Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Phris [ˌt̪un ˈfɾʲiʃ]) is a market town and former royal burgh in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, near the mouth of the River Nith on the Solway Firth, 25 miles (40 km) from the Anglo-Scottish border. Dumfries is the county town of the historic county of Dumfriesshire.[3]

Dumfries

| |

|---|---|

| Town and administrative centre | |

.jpg.webp) Dumfries High Street, with the Midsteeple in the background, pictured in August 2012 | |

Dumfries Location within Dumfries and Galloway | |

| Population | 33,470 (mid-2020 est.)[2] |

| Demonym | Doonhamer |

| OS grid reference | NX976762 |

| • Edinburgh | 63 mi (101 km) |

| • London | 285 mi (459 km) |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | DUMFRIES |

| Postcode district | DG1, DG2 |

| Dialling code | 01387 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Before becoming King of Scots, Robert the Bruce killed his rival the Red Comyn at Greyfriars Kirk in the town in 1306. The Young Pretender had his headquarters here towards the end of 1745. In the Second World War, the Norwegian Army in exile in Britain largely consisted of a brigade in Dumfries.

Dumfries is nicknamed Queen of the South.[4] This is also the name of the town's football club. People from Dumfries are known colloquially in Scots language as Doonhamers.

Toponymy

There are a number of theories on the etymology of the name, with an ultimately Celtic derivation (either from Brythonic, Gaelic or a mixture of both) considered the most likely.

The first element is derived either from the elements drum or dronn-,[5] (meaning "ridge" or "hump", also in Gaelic as druim[5]), or from Dùn meaning fort. One of the more commonly given etymologies is that the name Dumfries originates from the Scottish Gaelic name Dùn Phris, meaning "Fort of the Thicket".[6]

The second element is less obvious, but may be cognate with the Cumbric prēs, an element common in the Brythonic areas south of the River Forth.[5] As such, Dumfries has been suggested as a possible location of Penprys, the mysterious capital of a land in Medieval Welsh literature, most notably mentioned in the awdl, "Elegy for Gwallawg" by Taliesin.[5]

According to a third theory, the name is a corruption of two Old English or Old Norse words which mean "the Friars' Hill"; those who favour this idea allege the formation of a religious house near the head of what is now the Friars' Vennel.[7] If the name were English or Norse, however, the expected form would have the elements in reversed orientation (compare Clarendon). A Celtic derivation is therefore preferred.

History

Early history

No positive information has been obtained of the era and circumstances in which the town of Dumfries was founded.[7]

Some writers hold that Dumfries flourished as a place of distinction during the Roman occupation of North Great Britain. The Selgovae inhabited Nithsdale at the time and may have raised some military works of a defensive nature on or near the site of Dumfries; and it is more than probable that a castle of some kind formed the nucleus of the town. This is inferred from the etymology of the name, which, according to one theory, is resolvable into two Gaelic terms signifying a castle or fort in the copse or brushwood. Dumfries was once within the borders of the Kingdom of Northumbria. The district around Dumfries was for several centuries ruled over and deemed of much importance by the invading Romans. Many traces of Roman presence in Dumfriesshire are still to be found; coins, weapons, sepulchral remains, military earthworks, and roads being among the relics left by their lengthened sojourn in this part of Scotland. The Caledonian tribes in the south of Scotland were invested with the same rights by an edict of Antoninus Pius. The Romanized natives received freedom (the burrows, cairns, and remains of stone temples still to be seen in the district tell of a time when Druidism was the prevailing religion) as well as civilisation from their conquerors. Late in the fourth century, the Romans bade farewell to the country.[7]

According to another theory, the name is a corruption of two words which mean the Friars' Hill; those who favour this idea allege that St. Ninian, by planting a religious house near the head of what is now the Friars' Vennel, at the close of the fourth century, became the virtual founder of the Burgh; however Ninian, so far as is known, did not originate any monastic establishments anywhere and was simply a missionary. In the list of British towns given by the ancient historian Nennius, the name Caer Peris occurs, which some modern antiquarians suppose to have been transmuted, by a change of dialect, into Dumfries.[7]

Twelve of King Arthur's battles were recorded by Nennius in Historia Brittonum. The Battle of Tribruit (the tenth battle), has been suggested as having possibly been near Dumfries or near the mouth of the river Avon near Bo'ness.

After the Roman departure the area around Dumfries had various forms of visit by Picts, Anglo-Saxons, Scots and Norse culminating in a decisive victory for Gregory, King of Scots at what is now Lochmaben over the native Britons in 890.[7]

Medieval period

When, in 1069, Malcolm Canmore and William the Conqueror held a conference regarding the claims of Edgar Ætheling to the English Crown, they met at Abernithi – a term which in the old British tongue means a port at the mouth of the Nith. It has been argued, the town thus characterised must have been Dumfries; and therefore it must have existed as a port in the Kingdom of Strathclyde, if not in the Roman days. However, against this argument is that the town is situated eight to nine miles (14 km) distant from the sea,[7] although the River Nith is tidal and navigable all the way into the town itself.

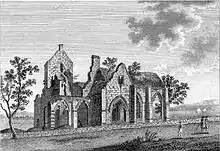

Although at the time 1 mile (1.6 km) upstream and on the opposite bank of the Nith from Dumfries, Lincluden Abbey was founded circa 1160. The abbey ruins are on the site of the bailey of the very early Lincluden Castle, as are those of the later Lincluden Tower. This religious house was used for various purposes, until its abandonment around 1700. Lincluden Abbey and its grounds are now within the Dumfries urban conurbation boundary. William the Lion granted the charter to raise Dumfries to the rank of a royal burgh in 1186. Dumfries was very much on the frontier during its first 50 years as a burgh and it grew rapidly as a market town and port.[8]

Alexander III visited Dumfries in 1264 to plan an expedition against the Isle of Man, previously Scots but for 180 years subjected by the crown of Norway. Identified with the conquest of Man, Dumfries shared in the well-being of Scotland for the next 22 years until Alexander's accidental death brought an Augustan era in the town's history to an abrupt finish.[7]

A royal castle, which no longer exists, was built in the 13th century on the site of the present Castledykes Park. In the latter part of the century William Wallace chased a fleeing English force southward through the Nith valley. The English fugitives met the gates of Dumfries Castle that remained firmly closed in their presence. With a body of the town's people joining Wallace and his fellow pursuers when they arrived, the fleeing English met their end at Cockpool on the Solway Coast. After resting at Caerlaverock Castle a few miles away from the bloodletting, Wallace again passed through Dumfries the day after as he returned north to Sanquhar Castle.[9]

During the invasion of 1300, Edward I of England lodged for a few days in June with the Minorite Friars of the Vennel, before he laid siege to Caerlaverock Castle at the head of the then greatest invasion force to attack Scotland. After Caerlaverock eventually succumbed, Edward passed through Dumfries again as he crossed the Nith to take his invasion into Galloway. With the Scottish nobility having requested Vatican support for their cause, Edward on his return to Caerlaverock was presented with a missive directed to him by Pope Boniface VIII. Edward held court in Dumfries at which he grudgingly agreed to an armistice. On 30 October, the truce solicited by Pope Boniface was signed by Edward at Dumfries. Letters from Edward, dated at Dumfries, were sent to his subordinates throughout Scotland, ordering them to give effect to the treaty. The peace was to last until Whitsunday in the following year.[7]

Before becoming King of Scots, Robert the Bruce stabbed his rival the Red Comyn at Greyfriars Kirk in the town on 10 February 1306. His uncertainty about the fatality of his stabbing caused one of his followers, Roger de Kirkpatrick, to utter the famous, "I mak siccar" ("I make sure") and finish the Comyn off. Bruce was subsequently excommunicated as a result, less for the murder than for its location in a church. Regardless, for Bruce the die was cast at the moment in Greyfriars and so began his campaign by force for the independence of Scotland. Swords were drawn by supporters of both sides, the burial ground of the Monastery becoming the theatre of battle. Bruce and his party then attacked Dumfries Castle. The English garrison surrendered and for the third time in the day Bruce and his supporters were victorious. He was crowned King of Scots barely seven weeks after. Bruce later triumphed at the Battle of Bannockburn and led Scotland to independence.

Once Edward received word of the revolution that had started in Dumfries, he again raised an army and invaded Scotland. Dumfries was again subjected to the control of Bruce's enemies. Sir Christopher Seton (Bruce's brother in law) had been captured at Loch Doon and was hurried to Dumfries to be tried for treason in general and more specifically for being present at Comyn's killing. Still in 1306 and along with two companions, Seton was condemned and executed by hanging and then beheading at the site of what is now St Mary's Church.

In 1659 ten women were accused of diverse acts of witchcraft by Dumfries Kirk Session although the Kirk Session minutes itself records nine witches. The Justiciary Court found them guilty of the several articles of witchcraft and on 13 April between 2 pm and 4 pm they were taken to the Whitesands, strangled at stakes and their bodies burnt to ashes.[10]

Eighteenth century

The Midsteeple in the centre of the High Street was completed in 1707.[11] Opposite the fountain in the High Street, adjacent to the present Marks & Spencer, was the Commercial and later the County Hotel. Although the latter was demolished in 1984–85, the original facade of the building was retained and incorporated into new retail premises.[12] The building now houses a Waterstones Bookshop. Room No. 6 of the hotel was known as Bonnie Prince Charlie's Room and appropriately carpeted in the Royal Stewart tartan. The timber panelling of "Prince Charlie's room" was largely reinstated and painted complete with the oil painted landscapes by Robert Norie (1720–1766) in the overmantels at either end of the room and can still be seen as the upstairs showroom of the book shop.[13] The Young Pretender had his headquarters here during a 3-day sojourn in Dumfries towards the end of 1745. £2,000 was demanded by the Prince, together with 1,000 pairs of brogues for his kilted Jacobite rebel army, which was camping in a field not one hundred yards distant. A rumour that the Duke of Cumberland was approaching, made Bonnie Prince Charlie decide to leave with his army, with only £1,000 and 255 pairs of shoes having been handed over.[14]

Robert Burns moved to Dumfriesshire in 1788 and Dumfries itself in 1791, living there until his death on 21 July 1796. Today's Greyfriars Church overlooks the location of a statue of Burns, which was designed by Amelia Robertson Hill, sculpted in Carrara, Italy in 1882, and was unveiled by future Prime Minister, Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery on 6 April 1882.[15] Today, it features on the 2007 series of £5 notes issued by the Bank of Scotland, alongside the Brig o' Doon.[16]

After working with Patrick Miller of Dalswinton, inventor William Symington intended to carry out a trial in order to show than an engine would work on a boat without the boat catching fire. The trial finally took place on Dalswinton Loch near Dumfries on 14 October 1788. The experiment demonstrated that a steam engine would work on a boat. Symington went on to become the builder of the first practical steamboat.

20th century and beyond

The first official intimation that RAF Dumfries was to be built was made in late 1938. The site chosen had accommodated light aircraft since about 1914. Work progressed quickly, and on 17 June 1940, the 18 Maintenance Unit was opened at Dumfries. The role of the base during the war also encompassed training. RAF Dumfries had a moment of danger on 25 March 1943, when a German Dornier Do 217 aircraft shot up the airfield beacon, but crashed shortly afterwards. The pilot, Oberleutnant Martin Piscke was later interred in Troqueer Cemetery in Dumfries town, with full military honours. On the night of 3/4 August 1943 a Vickers Wellington bomber with engine problems diverted to but crashed 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) short of the Dumfries runway.[17]

During the Second World War, the bulk of the Norwegian Army during their years in exile in Britain consisted of a brigade in Dumfries.[18] When the army High Command took over, there were 70 officers and about 760 privates in the camp. The camp was established in June 1940 and named Norwegian Reception Camp, consisting of some 500 men and women, mainly foreign-Norwegian who had volunteered for war duty in Norway during the Nazi occupation in early 1940. Through the summer the number was built up to around 1,500 under the command of General Carl Gustav Fleischer. Within a few miles of Dumfries are the villages of Tinwald, Torthorwald and Mouswald all of which were settled by Vikings.

Dumfries has experienced two Boxing Day earthquakes. These were in 1979 (measuring 4.7 ML centred near Longtown)[19] and 2006 (centred in the Dumfries locality measuring 3.6 ML ).[20] There were no serious consequences of either. There was also an earthquake on 16 February 1984[21] and a further earthquake on 7 June 2010.[22]

Demographics

The National Records for Scotland mid 2012 estimated population of Dumfries was reported as 33,280.[23][24]

Climate

As with the rest of the British Isles, Dumfries experiences a maritime climate (Cfb) with cool summers and mild winters. It is one of the less snowy locations in Scotland owing to its sheltered, low lying position in the South West of the country. From 2 July 1908 the town held the record for the highest temperature reading in Scotland, 32.8 °C (91.0 °F) until being surpassed in Greycrook on 9 August 2003.[25] Its southerly latitude makes little difference to the average annual temperatures compared to more northerly coastal parts of Scotland. This is due to strong maritime influence from the Irish Sea cooling down summers due to frequent cloudy weather and cool water temperatures. There are plenty of higher areas to Dumfries' west, but even so those seldom allow warm air to stay untouched.

| Climate data for Dumfries 49m asl, 1991–2020, extremes 1951–1980 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

28.6 (83.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.9 (35.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.9 (7.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−9 (16) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 121.7 (4.79) |

98.5 (3.88) |

86.3 (3.40) |

67.0 (2.64) |

69.2 (2.72) |

79.1 (3.11) |

82.9 (3.26) |

96.9 (3.81) |

90.7 (3.57) |

126.3 (4.97) |

130.3 (5.13) |

132.3 (5.21) |

1,181.2 (46.49) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47.0 | 72.1 | 102.6 | 149.0 | 185.8 | 147.2 | 151.0 | 146.4 | 115.1 | 90.5 | 59.3 | 43.8 | 1,309.8 |

| Source 1: Met Office[26] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: ScotClim[27] | |||||||||||||

Geography

Like the rest of Dumfries and Galloway, of Scotland's three major geographical areas Dumfries lies in the Southern Uplands.

The river Nith runs through Dumfries toward the Solway Firth in a southwards direction splitting the town into East and West. At low tide, the sea recedes to such an extent on the shallow sloping sands of the Solway that the length of the Nith is extended by 13 km to 113.8 km (70.7 mi). This makes the Nith Scotland's seventh longest river. There are several bridges across the river within the town. In between the Devorgilla (also known as 'The Old Bridge') and the suspension bridge is a weir colloquially known as 'The Caul'. In wetter months of the year the Nith can flood the surrounding streets. The Whitesands has flooded on average once a year since 1827.[28]

Dumfries has numerous suburbs including Summerhill, Summerville, Troqueer, Georgetown, Cresswell, Larchfield, Calside, Lochside, Lincluden, Newbridge Drive, Sandside, Heathhall, Locharbriggs, Noblehill and Marchmount. Maxwelltown to the west of the river Nith, was formerly a burgh in its own right within Kirkcudbrightshire until its incorporation into Dumfries in 1929; Summerhill, Troqueer, Lochside, Lincluden, Sandside are among other suburbs located on the Maxwelltown side of the river. Palmerston Park, home to the town's senior football team Queen of the South, is on Terregles Street, also on the Maxwelltown side of the river.

Queensberry Square and High Street are the central focal points of the town and this area hosts many of the historical, social and commercial enterprises and events of Dumfries. During the 1990s, these areas enjoyed various aesthetic recognitions from organisations including Britain in Bloom.

Governance

Scottish communities granted Royal Burgh status by the monarch guarded the honour jealously and with vigour. Riding the Marches maintains the tradition of an occasion that was, in its day, of great importance. Dumfries has been a Royal Burgh since 1186, its charter being granted by King William the Lion in a move that ensured the loyalty of its citizens to the Monarch.

Although far from the centre of power in Scotland, Dumfries had obvious strategic significance sitting as it does on the edge of Galloway and being the centre of control for the south west of Scotland.

With the River Nith on two sides and the Lochar Moss on another, Dumfries was a town with good natural defences. Consequently, it was never completely walled. A careful eye still had to be kept on the clearly defined boundaries of the burgh, a task that had to be taken each year by the Provost, Baillies, Burgesses and others within the town.

Neighbouring landowners might try to encroach on the town boundaries, or the Marches as they were known, moving them back 100 yards or so to their own benefit. It had to be made clear to anyone thinking of or trying to encroach that they dare not do so.

In return for the Royal status of the town and the favour of the King, the Provost and his council, along with other worthies of the town had to be diligent in ensuring the boundaries were strictly observed. Although steeped in history, Scotland's burghs remained the foundation of the country's system of local government for centuries. Burgh status conferred on its citizens the right to elect their own town councils, run their own affairs and raise their own local taxes or rates.

Dumfries also became the administrative centre for the shire of Dumfries, or Dumfriesshire, which was probably created in the twelfth century and certainly existed by 1305.[29] When elected county councils were created in 1890 under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889, the burgh of Dumfries was deemed capable of running its own affairs and so was excluded from the jurisdiction of the county council.[30][31]

The burgh of Dumfries was enlarged in 1929 to take in Maxwelltown on the west bank of the Nith, which had previously been a separate burgh in Kirkcudbrightshire.[32][33] Further local government reform in 1930 brought the burgh of Dumfries within the area controlled by Dumfriesshire County Council, but classed as a large burgh which allowed the town to continue to run many local services itself.[34] The town council was based at Municipal Buildings in Buccleuch Street, built in 1932 on the site of an earlier council building.[35]

In 1975 local government across Scotland was reformed under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973. The burghs and counties were abolished as administrative areas, replaced with a two-tier system of upper-tier regions and lower-tier districts.[36] Dumfries therefore became part of the Nithsdale district in the region of Dumfries and Galloway. Nithsdale District Council took over the Municipal Buildings.[35] Ancient titles associated with Dumfries' history as a royal burgh like provost and bailie were discarded or retained only for ceremonial purposes. Robes and chains often found their way into museums as a reminder of the past. Further local government reform in 1996 abolished Nithsdale district, since when Dumfries has been governed by Dumfries and Galloway Council, which has its headquarters in the town at County Buildings, which had been built in 1914 as the headquarters of Dumfriesshire County Council.[37]

Dumfries remains a centre of local government for a much bigger area than just the town itself. But its people, the Doonhamers still retain a pride in their town and distinctive identity. This is never more so than during the week-long Guid Nychburris Festival and its highlight the Riding of the Marches which takes place on the third Saturday in June each year.

Politics

Dumfries is located in the council area of Dumfries and Galloway. It is the seat of the local council, whose headquarters are located on the edge of the town centre. Until 1995 Dumfries was also home to the council for the local district of Nithsdale. Dumfries also lends its name to the lieutenancy area of Dumfries, which is similar in boundaries to the former Dumfriesshire county.

Dumfries is split into two UK Parliament constituencies: Dumfries and Galloway which is represented by current Secretary of State for Scotland, Alister Jack and Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale which is represented by David Mundell, both of the Scottish Conservative Party.

For Scottish Parliament elections, Dumfries is in the South Scotland electoral region and split between two constituencies. The western wards of Abbey and North West Dumfries are in the constituency of Galloway and West Dumfries, while the eastern wards of Nith and Lochar are in the constituency of Dumfriesshire. The respective MSPs are Finlay Carson and Oliver Mundell, both of the Scottish Conservative Party.

In the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, Dumfries and Galloway had the country's third heaviest 'No' vote at more than 65% of the ballots cast. That was more than 10 points higher than the national average pro-union vote.

On the Dumfries and Galloway Council, Dumfries is covered by four 4-seat wards: Abbey, Lochar, Nith and North West Dumfries. North West Dumfries is the only ward that solely covers areas within the town itself, with the others incorporating outlying areas. In the 2017 council election, these wards elected 6 Labour, 5 Conservative and 4 SNP councillors.

Economy

Dumfries has a long history as a county town, and as the market town of a surrounding rural hinterland. The North British Rubber Company started manufacturing in 1946 at Heathhall on the former site of the Arrol-Johnston Motor Company which was said to be the most advanced light engineering factory of its day in Scotland. It became Uniroyal Ltd in the 1960s and was where the Hunter Boot and Powergrip engine timing belts were manufactured. In 1987 it changed name to the British subsidiary of the Gates Rubber Company and later was known as Interfloor from 2002 until the factory closed in 2013.

Dumfries is a relatively prosperous community but the town centre has been exposed to the centrifugal forces that have seen retail, business, educational, residential and other uses gravitate towards the town's urban fringe.[38] This was started in the 1980s with the building of the Dumfries bypass. The immediate effect of this was as intended the diversion of transiting traffic away from the town centre. This brought with it an accompanying reduction in economic input to the town centre. The second effect of this has been more pronounced. Sites close to the bypass have attracted development to utilise the bypass as a high speed urban highway without the bottlenecks of the town centre and without the constraining limited town centre parking.

In a bid to re-stimulate development in Dumfries town centre, both economically and in a social context, several strategies have been proposed by the controlling authorities.[39]

Culture

Dumfries got its nickname 'Queen of the South' from David Dunbar, a local poet,[40] who in 1857 stood in the general election. In one of his addresses he called Dumfries "Queen of the South" and this became synonymous with the town.[41][42]

The term doonhamer comes from the way that natives of Dumfries over the years have referred to the area when working away from home. The town is often referred to as doon hame in the Scots language (down home). The term doonhamer followed, to describe those that originate from Dumfries.[41]

The Doonhamers is also the nickname of Queen of the South who represent Dumfries and the surrounding area in the Scottish Football League.[41]

The crest of Dumfries contains the words, "A Lore Burne". In the history of Dumfries close to the town was the marsh through which ran the Loreburn whose name became the rallying cry of the town in times of attack – A Lore Burne (meaning 'to the muddy stream').[41][43]

In 2017 Dumfries was ranked the happiest place in Scotland by Rightmove.[44]

Museums

Located on top of a small hill, Dumfries Museum is centred on the 18th-century windmill which stands above the town. Included are fossil footprints left by prehistoric reptiles, the wildlife of the Solway marshes, tools and weapons of the earliest peoples of the region and stone carvings of Scotland's first Christians. On the top floor of the museum is a camera obscura.[43]

Based in the control tower near Tinwald Downs, the aviation museum has an extensive indoor display of memorabilia, much of which has come via various recovery activities. During the second world war, aerial navigation was taught at Dumfries also at Wigtown and nearby Annan was a fighter training unit. RAF Dumfries doubled as an important maintenance unit and aircraft storage unit. The museum is run by the Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Group and is the only private aviation museum in Scotland.[45] The restored control tower of the former World War II airfield is now a listed building. The museum is run by volunteers and houses a large and ever expanding aircraft collection, aero engines and a display of artefacts and personal histories relating to aviation, past and present. It is also home to the Loch Doon Spitfire. Both civil aviation and military aviation are represented.[17]

Theatre and cinema

The Theatre Royal, Dumfries was built in 1792 and is the oldest working theatre in Scotland.[47]

The theatre is owned by the Guild of Players who bought it in 1959, thereby saving it from demolition, and is run on a voluntary basis by the members of the Guild of Players. It is funded entirely by Guild membership subscriptions, and by box office receipts. It does not currently receive any grant aid towards running costs.

In recent years the theatre has been re-roofed and the outside refurbished. It is the venue for the Guild of Players' own productions and for performances from visiting companies. These include: Scottish Opera, TAG, the Borderline and 7:84.

The Robert Burns Centre is an art house cinema in Dumfries.[48] The Odeon Cinema, which showed more mainstream movies, closed its doors in mid-2018 due to the local council refusing to allow Odeon to relocate, forcing them to close.

Concert and event venues

The Loreburn Hall (sometimes known colloquially as The Drill Hall)[49] has hosted concerts by performers such as Black Sabbath,[50] Big Country,[51] The Proclaimers and Scottish Opera.[49] The hall has hosted sporting events such as wrestling.[52] The new DG One sport, fitness and entertainment centre became the principal indoor event venue in Dumfries in 2007,[53] but in October 2014, it closed due to major defects being discovered in the building. However, the refurbished building reopened to the public in the summer of 2019.[54] The Theatre Royal has also reopened following renovation work.

Visual arts

With a collection of over 400 Scottish paintings, Gracefield Arts Centre hosts a changing programme of exhibitions featuring regional, national and international artists and craft-makers.[55]

Dumfries Art Trail brings together artists, makers, galleries and craft shops with venues accessible all year round.[56]

Festivals

There are a number of festivals which take place throughout the year, mostly based on traditional values.

Guid Nychburris (Middle Scots, meaning Good Neighbours) is the main festival of the year, a ceremony which is largely based on the theme of a positive community spirit.

The ceremony on Guid Nychburris Day, follows a route and sequence of events laid down in the mists of time. Formal proceedings start at 7.30 am with the gathering of up to 250 horses waiting for the courier to arrive and announce that the Pursuivant is on his way, and at 8.00 am leave the Midsteeple and ride out to meet the Pursuivant. They then proceed to Ride the Marches and Stob and Nog (mark the boundary with posts and flags) before returning to the Midsteeple at 12.15 pm to meet the Provost and then the Charter is proclaimed to the towns people of Dumfries. This is then followed by the crowning of the Queen of the South.[57]

Since 2013, Dumfries has seen the annual Nithraid, a small boat race up the Nith from Carsethorn, celebrating the town's historical relationship with the river.

The region is also home to a number of thriving music festivals such as the Eden Festival (at St Ann's near Moffat), Youthbeatz (Scotland's largest free youth music festival), the Moniaive Folk Festival, Thornhill Music Festival, Big Burns Supper Festival and previously Electric Fields at Drumlanrig Castle.

Library

The Ewart Library is a Carnegie library, and was opened in 1904. Carnegie donated £10,000 toward the building of the library, and suggested that it was named after William Ewart, former MP for the area, and who was key in the introduction of acts of Parliament in both England and Scotland related to the creation of public libraries.[58]

Religion

The churches and chapels of the Presbyterian and other communions are, many of them, fine buildings. St Michael's (1746), a stately pile, was the church which Robert Burns attended, and in its churchyard he was buried, his remains being transferred in 1815 to the magnificent mausoleum erected in the south-east corner, where also lie his wife, Jean Armour, and several members of his family. The Gothic church of Greyfriars (1866–1867) occupies the site partly of a Franciscan monastery and partly of the old castle of the town. On the site of St Mary's (1837–1839), also Gothic, stood the small chapel raised by Christiana, sister of Robert Bruce, to the memory of her husband, Sir Christopher Seton, who had been executed on the spot by Edward I. St Andrew's (1811–1813), in the Romanesque style, is a Roman Catholic church, which also serves as the pro-cathedral of the diocese of Galloway.[59] In 1851 Lewis wrote about other churches saying that an episcopal chapel was erected in 1817, at a cost of £'2200 ; and there are places of worship for members of the Free Church, the United Presbyterian Church, Reformed Presbyterians, Independents, and Wesleyans, and a Roman Catholic chapel.[60] Churches have closed and opened since then.[61]

Sport

Queen of the South represent Dumfries and the surrounding area in the third level of the country's professional football system, the Scottish League One. Palmerston Park on Terregles Street is the home ground of the team. This is on the Maxwelltown side of the River Nith. They reached the 2008 Scottish Cup Final, losing 3–2 to Rangers.[41]

Dumfries City VFC are a virtual football club from the town.

Dumfries Saints Rugby Club is one of Scotland's oldest rugby clubs having been admitted to the Scottish Rugby Union in 1876–77 as "Dumfries Rangers".[62]

Dumfries is also home to a number of golf courses:

- The Crichton Golf Club

- The Dumfries and County Golf Club

- The Dumfries and Galloway Golf Club

Of those is listed only the Dumfries and Galloway Golf Club is on the Maxwelltown side of the River Nith. This course is also bisected into 2 halves of 9 holes each by the town's Castle Douglas Road. The club house and holes 1 to 7 and 17 and 18 are on the side nearest to Summerhill, Dumfries. Holes 8 to 16 are on the side nearest to Janefield.

The opening stage of the 2011 Tour of Britain started in Peebles and finished 105.8 miles (170.3 km) later in Dumfries. The stage was won by sprint specialist and reigning Tour de France green jersey champion, Mark Cavendish, with his teammate lead out man, Mark Renshaw finishing second. Cavendish had been scheduled to be racing in the 2011 Vuelta a España. However Cavendish was one a number of riders to withdraw having suffered in the searing Spanish heat. This allowed Cavendish to be a late addition to the Tour of Britain line up in his preparation for what was to be a successful bid two weeks later in the 2011 UCI Road World Championships – Men's road race. Cavendish in a smiling post race TV interview in Dumfries described the wet and windy race conditions through the Southern Scottish stage as 'horrible'.[63]

DG One complex includes a national event-sized competition swimming pool.

The David Keswick Athletic Centre is the principal facility in Dumfries for athletics.[64]

Dumfries is home to Nithsdale Amateur Rowing Club.[65][66] The rowers share their clubhouse with Dumfries Sub-Aqua Club.[67]

The town is also home to Solway Sharks ice hockey team. The team are current Northern Premier League winners. The team's home rink is Dumfries Ice Bowl. Dumfries Ice bowl is also recognised as Scotland's only centre of ice hockey excellence, and trials for the Scottish Jr national team are carried out at this venu.

Dumfries Ice Bowl is also home to two synchronised skating teams, Solway Stars and Solway Eclipse. In addition, Dumfries Ice Bowl is also home to several curling teams, competitions and leagues. Junior curling teams from Dumfries, consisting of curlers under the age of 21, regularly compete in the Dutch Junior Open based in Zoetermeer, the Netherlands. In 2007, 2008 and 2009 a Dumfries-based team have been the winners of the competition's Hogline Trophy.

Dumfries hosts three outdoor bowls clubs:[68]

- Dumfries Bowling Club

- Marchmount Bowling Club

- Maxwelltown Bowling Club

Dumfries hosts cycling organisations and cycling holidays.[69][70][71]

Education

Dumfries has several primary schools, approximately one per key district, and four main secondary schools. All of these institutions are governed by Dumfries and Galloway council. The secondary schools are:

Dumfries Academy was a grammar school until adopting a comprehensive format in 1983.

In 2013 plans for a 'super school' were announced. These plans were later dismissed in favour of renovating existing schools.[72]

In 1999 Scotland's first multi-institutional university campus was established in Dumfries, in the 85-acre (340,000 m2) Crichton estate. In order of campus presence it is host to the University of the West of Scotland (UWS) (formerly known as University of Paisley & Bell College), Dumfries & Galloway College, and the University of Glasgow. Still in its infancy, the campus offers a range of degree courses in initial teacher education, business, computing, environmental studies, tourism, heritage, social work, health, social studies, nursing, liberal arts and humanities.[73][74] Despite the short-lived threat of closure to the University of Glasgow part of the campus in 2006, a campaign by students, academics and local supporters ensured that the University of Glasgow remained open in Dumfries. The University of Glasgow, since maintaining its provision in Dumfries, has launched a new undergraduate programme in primary teaching.[75]

Healthcare

Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary is the principal secondary care referral centre for Dumfries and Galloway region. It now includes a maternity wing which replaced the old Cresswell Maternity Hospital.

Midpark Hospital, close to the site of the former Crichton Royal Hospital, is part of the Dumfries and Galloway NHS Board and provides a regional psychiatric, psychological and specialist addictions service within Dumfries and Galloway. In 1838 William A. F. Browne accepted the position of Physician Superintendent at the newly created Crichton. It is at the Crichton where Ursula Fleming gained much of her education and experience.

Transport

.jpg.webp)

Dumfries is linked to the Northbound A74(M) motorway at Beattock via the A701 road. The A75 road eastbound links Dumfries to the southbound A74(M), leading to the M6 motorway and Carlisle. The A75 road west links Dumfries with the ferry port of Stranraer. The A76 road connects to Kilmarnock in Ayrshire.

Dumfries railway station lies on the Glasgow South Western Line. It was awarded Best Station Awards by British Rail in 1986 and 1987. The train service is now operated by ScotRail which provides services to Glasgow Central and Carlisle, and less frequent services direct to Newcastle. The nearest station to Dumfries on the West Coast Main Line is 14 miles (23 km) east along the A709 road at Lockerbie, and the nearest West Coast Main Line station linking directly to Dumfries by rail is Carlisle.

Maxwelltown station in the Summerhill district of the town was closed along with the direct line to Stranraer via Castle Douglas as part of the Beeching cuts in 1965. Part of the disused railway track in Dumfries was later converted to a cycle path.

Parks

The most significant of the parks in Dumfries are all within walking distance of the town centre:-

- Dock Park – located on the East bank of the Nith just to the South of St Michael's Bridge

- Castledykes Park – as the name suggests on the site of a former castle

- Mill Green (also known as deer park, although the deer formerly accommodated there have since been relocated) – on the West bank of the Nith opposite Whitesands

Broadcasting

Dumfries was formerly home to one of the 11 BBC studios in Scotland.

Greatest Hits Radio Dumfries & Galloway, part of Bauer Media Group, broadcasts from Dumfries, and is also the main radio station for the area. Community radio station Alive 107.3 broadcasts on 107.3FM in Dumfries and online.[76]

In 2018, Dumfries got a new radio station, Dumfries Community Radio. Also known as DCR Online, it is not a traditional FM radio station, but an online radio station.

Local journalism

The two local newspapers that specifically cover Dumfries and the surrounding are:-

- Dumfries and Galloway Standard[77] (established 1843) publishing on Tuesdays and Fridays

- Dumfries Courier[78] publishing on Fridays

Architectural geology

There are many buildings in Dumfries made from sandstone of the local Locharbriggs quarry.

The quarry is situated off the A701 on the north of Dumfries at Locharbriggs close to the nearby aggregates quarry. This dimension stone quarry is a large quarry. Quarry working at Locharbriggs dates from the 18th century, and the quarry has been worked continuously since 1890.[79]

There are good reserves of stone that can be extracted at several locations. On average the stone is available at depths of 1m on bed although some larger blocks are obtainable. The average length of a block is 1.5m but 2.6m blocks can be obtained.

Locharbriggs is from the New Red Sandstone of the Permian age. It is a medium-grained stone ranging in colour from dull red to pink. It is the sandstone used in the Queen Alexandra Bridge in Sunderland, the Manchester Central Convention Complex and the base of the Statue of Liberty.[79]

- Examples of sandstone carvings found in Dumfries

Minerva building, Dumfries Academy

Minerva building, Dumfries Academy Detail at Greyfriar's church

Detail at Greyfriar's church Detail at Greyfriars church

Detail at Greyfriars church Detail at Midsteeple

Detail at Midsteeple Detail at Queensberry hotel

Detail at Queensberry hotel Ram's head at Queensberry monument

Ram's head at Queensberry monument Greyfriars Dumfries town centre

Greyfriars Dumfries town centre Carving of Pan

Carving of Pan Detail at Dumfries Academy

Detail at Dumfries Academy

Surrounding places of interest

As the largest settlement in Southern Scotland, Dumfries is recognised as a centre for visiting surrounding points of interest.[80] The following are all within easy reach:

- Ae village and forest

- Caerlaverock Castle[45]

- Criffel – a hill on the Solway Coast popular with hill walkers for its views of the Southern Scottish coastline and across the Solway Firth to the Lake District of Cumbria

- Drumlanrig Castle[45]

- Ecclefechan – Thomas Carlyle's birthplace "The Arched House" is a tourist attraction and has been maintained by the National Trust for Scotland since 1936.[45] Ecclefechan lies at the foot of the large Roman Fort, Burnswark, which dominates the horizon with its flat top.

- Glencaple Quay - Old harbour, restaurant, shop and views of the River Nith.

- Gretna Green and the Old Blacksmith's Shop famous for runaway marriages.[45]

- John Paul Jones Cottage Museum – The traditional Scottish cottage in which John Paul Jones was born in 1747.[81]

- Kingholm Quay - 18th century harbour, on the east side of the River Nith, that once served the town.

- Laghall Quay - 18th century harbour, on the west side of the River Nith, A pleasant walk to the site and views of the Nith and Kingholm Quay.

- Kagyu Samye Ling Monastery and Tibetan Centre was the first Tibetan Buddhist Centre to have been established in the West. It is a centre within the Karma Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. It is in the village of Eskdalemuir in the Scottish Southern Uplands[82]

- Lochmaben with its lochs popular with boaters and also its history with Robert the Bruce

- Mabie Forest – popular destinations for outdoor recreation such as mountain bike and walking

- Moffat and the views nearby of The Devil's Beef Tub, The Grey Mare's Tail waterfall and the A708 from Moffat past the Grey Mare's Tail to St Mary's Loch.

- Moniaive conservation village

- New Abbey Corn Mill Museum and Sweetheart Abbey[45]

- Solway Coast

- Threave Castle in Castle Douglas, Built in the 1370s by Archibald the Grim, 3rd Earl of Douglas. Now a ruin, it was a stronghold of the "Black Douglases", Earls of Douglas and Lords of Galloway, until their fall in 1455.

- Twynholm and the David Coulthard Museum.[45]

- Wanlockhead – Britain's highest village registered at 1,531 feet (467 m) above sea level and the Lead Mining Museum[45]

Notable people

A number of well-known people were educated at Dumfries Academy, among them Henry Duncan, founder of the world's first commercial savings bank, Sir James Anderson, who captained the SS Great Eastern on the transatlantic telegraph cable laying voyages in 1865 and 1866,[83] James Matthew Barrie, author of Peter Pan, musician John Law Hume of the Titanic orchestra, Jane Haining, international diplomat Alexander Knox Helm, John Laurie, actor (Private Fraser in Dad's Army), artist Christian Jane Fergusson, artist Sir Robin Philipson, singer John Hanson, Alex Graham, cartoonist best known for the Fred Basset series and Jock Wishart, who in 1998 set a new world record for circumnavigating the globe in a powered vessel.[84][85] Roger White, CEO of soft drinks group A.G. Barr is a local lad who went to Dumfries Academy. Following William A. F. Browne's 1838 appointment as Superintendent of the Crichton hospital, his son, James Crichton-Browne, was educated at the academy.

William Charles Wells, predecessor to Charles Darwin on the theory of natural selection was another schooled in Dumfries. Geologist Robert Harkness was schooled in Dumfries and subsequently resided in the town. Sir Frank Williams of F1 motor racing fame was educated at St Joseph's College, Dumfries as was Charles Forte, Baron Forte. St Joseph's was founded by Brother Walfrid, the founder of Celtic F.C.

International chart-topping record producer Calvin Harris is from Dumfries. Dumfries was the hometown of Calvin Harris until he left in 2008. Ray Wilson, lead singer of Stiltskin and later Genesis was born in Dumfries as were fellow musicians Geoffrey Kelly and Ian Carr and Emma's Imagination singer Emma Gillespie is from Dumfries. Opera singer Nicky Spence was born in Dumfries as was Britain's Got Talent singer Andrew Johnston. Nigel Sinclair CBE is a Hollywood film producer. Michael Carter's acting career has seen him appear in a variety or productions ranging from Return of the Jedi to Rebus.

Dumfries has produced a steady stream of professional footballers and managers. The best known footballers of their eras to come from Dumfries are probably Dave Halliday,[86] Ian Dickson,[86] Bobby Ancell, Billy Houliston,[86] Jimmy McIntosh,[87] Willie McNaught and Ted McMinn.[86] Halliday, Dickson, Houliston and McMinn played for home town club, Queen of the South during their careers. Dominic Matteo[88][89] was born in Dumfries but moved to England while still a young boy. Barry Nicholson lost 4–3 to Queens playing for Aberdeen in the 2008 Scottish Cup semi-finals despite scoring[41] against the team he supported as a boy.[89] Ancell, Houliston, McNaught and Nicholson have represented Scotland and were joined in having done so in season 2010/11 by Cammy Bell and Grant Hanley. Matteo gained 6 full caps for Scotland[89] after having represented England at under-21 level. Halliday was overlooked by Scotland in favour of Hughie Gallacher.[86] Gallacher played for The Queen's but was not from Dumfries. It was as a manager rather than a player that Thomas Mitchell made his name as a multiple FA Cup winner at Blackburn Rovers[90] before joining Woolwich Arsenal as Arsenal F.C. were then named.

Dumfries is also the hometown of three-times 24 Hours of Le Mans winner, Allan McNish,[91] as it was to fellow racing driver David Leslie.[91] Scotland rugby union internationalists Duncan Hodge, Nick De Luca, Craig Hamilton and Alex Dunbar were born in Dumfries as were professional golfers Andrew Coltart[92] and Robert Dinwiddie. Curling world champions David Murdoch, Euan Byers and Craig Wilson were all born in Dumfries. Former darts champion Rab Smith is another Doonhamer.

BBC Broadcaster Kirsty Wark was born in the town as was fellow broadcaster Stephen Jardine.[93] Neil Oliver (archaeologist, historian, author and broadcaster), grew up in Ayr and Dumfries. Author and earth scientist Dougal Dixon is from Dumfries. Hunter Davies (author, journalist and broadcaster) lived in Dumfries for four years as a boy.[94] James Hannay as well as being a novelist and journalist spent the last five years of his life as the British consul in Barcelona. John Mayne was born in Dumfries in 1759 and contributed in the field of poetry. World War I poet William Hamilton was another born in Dumfries. Archibald Gracie, shipping magnate and business tycoon in USA, was from Dumfries. Banking executive John McFarlane originates from the town. The architect George Corson who worked mainly in Leeds, England, was born in Dumfries and articled to Walter Newall in the town.

Politician David Mundell was born in Dumfries as were William Dickson, William Pattison Telford Sr. and Ambrose Blacklock all of whom made their mark politically in Canada. Malcolm H. Wright was also born in Dumfries, father of Sophie B. Wright – New Orleans' educator and pioneer for women and children's rights. Suffragette and feminist campaigner Dora Marsden spent the last 25 years of her life being cared for in Dumfries after her psychological breakdown. Dr Ian Gibson is another to leave his mark on politics. James Edward Tait was a Dumfries-born recipient of the Victoria Cross. William Robertson and Edward Spence are other Victoria Cross recipients. Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, UK Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, was quartered in Dumfries in 1796 during his military service.

David Haggart (1801–1821), was a Scottish thief and rogue who in 1820 in his escape from Dumfries Gaol, (site now occupied by Thomson's the Jewellers ), killed the turnkey. He was hanged in Edinburgh in 1821. His dictated memoir published as a chapbook[95] became the subject of the 1969 John Huston film "Sinful Davey" starring John Hurt.

A plaque on the wall on the site of the King's Arms Hotel, now Boots the Chemist's, records the presence there in 1829 of William Hare of Burke and Hare notoriety. He was travelling to Ireland after the trial; his visit caused a near riot.[96] John Richardson, naturalist, explorer and naval surgeon was born in Dumfries as was John Craig, mathematician, and polymath James Crichton. Benjamin Bell after being born in Dumfries went on to become considered the first Scottish scientific surgeon. His great-grandson was Joseph Bell who Arthur Conan Doyle has credited Sherlock Holmes as being loosely based on from Bell's observant manner. Doyle's father, artist Charles Altamont Doyle, died in The Crichton Royal Institution and is buried in the High Cemetery in Dumfries.[97]

Thomas Peter Anderson Stuart left Dumfries to go on and found the University of Sydney Medical School. John Allan Broun's contribution to science were his discoveries around magnetism and meteorology. James Braid, surgeon and pioneer of hypnotism and hypnotherapy, practised in Dumfries from 1825 to 1828 in partnership with William Maxwell. Ian Callum is eminent in the world of motor engineer. A Church of Scotland minister the Rev. John Ewart of Troqueer in Kirkcudbrightshire produced eleven children of whom some have made a notable mark. Peter Ewart was an engineer who was influential in developing the technologies of turbines and theories of thermodynamics. His brother Joseph Ewart became British ambassador to Prussia. John, a doctor, became Chief Inspector of East India Company hospitals in India. William, father of William Ewart, was business partner of Sir John Gladstones (sic), father of four times Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. Gladstone junior was named after Ewart, his godfather. James Julius Wood was an early minister at St George's and a Free Church Moderator.

Places of the same name

Canada

- Dumfries, New Brunswick in Canada

- South Dumfries Township, Ontario, Canada

- North Dumfries, Ontario, Canada

United States

- Dumfries, Virginia in the US was formally established on land at the head of the harbour of Quantico Creek, provided by John Graham. He named the town after his birthplace, Dumfries in Scotland.

- Dumfries, Minnesota, USA

- Dumfries, Iowa,[98] USA

Other

- Dumfries, Cat Island, Bahamas[99]

- Dumfries, on the Grenadine island of Carriacou, Grenada[100]

Twin towns

![]() – Annapolis, Maryland,[101] is home to the United States Naval Academy where John Paul Jones lies in the crypt beneath the chapel.

– Annapolis, Maryland,[101] is home to the United States Naval Academy where John Paul Jones lies in the crypt beneath the chapel.

![]() – Cantù, Italy. Dumfries and Galloway Council has not been involved in any official twinning link between the two towns for some time. The bond has been maintained through the Friends of Cantu and the Nithsdale Twinning Association.[103]

– Cantù, Italy. Dumfries and Galloway Council has not been involved in any official twinning link between the two towns for some time. The bond has been maintained through the Friends of Cantu and the Nithsdale Twinning Association.[103]

See also

- Abecediary—An example from St Mary Grey Friars church

- List of places in Dumfries and Galloway

References

- "Gaelic Place-Names of Scotland database". Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- John Thomson's Atlas of Scotland, 1832 from National Library of Scotland Retrieved 3 June 2013

- ""Eva Mendes – the latest Queen of the South" 7 November 2010". Qosfc.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- James, Alan. "A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence" (PDF). SPNS – The Brittonic Language in the Old North. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- "Parliament Scotland – Placenames – Gaelic – C-E" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "History of the Burgh of Dumfries – Chapter I". Electricscotland.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- M'Dowall, William (1867). History of the burgh of Dumfries: with notices of Nithsdale, Annandale, and the western border. Adam and Charles Black. p. 144.

- "Sanquar Castle". Castles of Scotland. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- "Dumfries Museum". Dumfriesmuseum.demon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "High Street, Midsteeple (LB26215)". Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "County Hotel, 79 High Street, Dumfries (LB26218)". Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- Holloway, James (1994). The Norie Family. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland. p. 27. ISBN 0903598442.

- "Walks in Burns Country – Town Centre". Electricscotland.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Burns Statue, Dumfries with Tam O'Shanter and Souter Johnnie statues "on tour", c 1900". National Burns Collection. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "Current Banknotes: Bank of Scotland". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Museum". Dumfriesaviationmuseum.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Giancarlo Rinaldi (4 November 2010). "Dumfries remembers role as home to Norwegian army". BBC Scotland. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- Musson, R. M. W.; Henni, P. H. O. (1 December 2002). "The felt effects of the Carlisle earthquake of 26 December 1979". Scottish Journal of Geology. 38 (2): 113–125. doi:10.1144/sjg38020113. S2CID 140171007 – via sjg.lyellcollection.org.

- "Dumfries Earthquake 26 December 2006". British Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Redmayne D. W., 1984. "The Dumfries earthquake of 16 February 1984". BGS; Global Seismology Report No. 241

- ""Mid-2012 Populations Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland, table 2a" National Records for Scotland" (PDF). Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Mid-2012 Populations Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland, table 3a" National Records for Scotland|access-date = 27 October 2014

- "1908 temperature". UKMO. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Dumfries 1991–2020 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- "Dumfries 1951–1980 extremes". www.weather.org.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-south-scotland-66867199

- Chalmers, George (1824). "Of its establishment as a Shire". Caledonia. London. pp. 68–70. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889, sections 8 and 105

- "The Local Government Act in Dumfriesshire". Annandale Observer. Annan. 27 September 1889. p. 3. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "Maxwelltown Burgh". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "Dumfries-Maxwelltown Amalgamation". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 4 October 1929. p. 14. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "Local Government (Scotland) Act 1929", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1929 c. 25, retrieved 23 December 2022

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Nithsdale District Council Offices, Dumfries (Category C Listed Building) (LB26099)". Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- "Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1973 c. 65, retrieved 23 December 2022

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Dumfries County Buildings, 113 English Street, Dumfries (LB26174)". Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- "DGC -Document: Dumfries Town Centre Urban Design Strategy – Part 1". Archived from the original on 15 February 2008.

- "MiniWeb: Regeneration & Europe – Dumfries Town Centre". Dumfriesregeneration.co.uk. 15 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Robert Temple Bibliographical Archive". Telinco.co.uk. 2 March 2008. Archived from the original on 5 November 2003. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Queen of the South club history". Qosfc.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Ritchie, Robert. ""Best town nickname" The Scotsman 1 August 2009". Thescotsman.scotsman.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Dumfries and Galloway Museums and Galleries on-line". Dumfriesmuseum.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Dumfries ranked the happiest place to live in Scotland". ITV News. 11 October 2017.

- "Dumfries and Galloway Museums". Dumfriesmuseum.demon.co.uk. 1 August 1999. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "St. Andrew's Catholic Church Dumfries website". Archived from the original on 27 March 2014.

- "Guild of Players – Home". Guildofplayers.co.uk. June 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Robert Burns Centre Film Theatre". Rbcft.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Scotland: Loreburn Hall, Dumfries". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- "1970 Tour". Black-sabbath.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Tour Dates 1990". 22 October 1999. Archived from the original on 22 October 1999.

- "wZw Present The 'Destruction Tour'". Wrestling101.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "MiniWeb". DG One. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Dumfries leisure centre with 'unique' failings ready to reopen". BBC News. 26 June 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Gracefield Arts centre". Dumfriesmuseum.demon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "DART 2017". Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "www.guidnychburris.co.uk". guidnychburris.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Edwardian Renaissance Architecture in Scotland". www.scotcities.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dumfries". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Lewis, Samuel (1851). "Dumfries". A topographical dictionary of Scotland, comprising the several counties, islands, cities, burgh and market towns, parishes, and principal villages, with historical and statistical descriptions: embellished with engravings of the seals and arms of the different burghs and universities. Vol. 1. London: S. Lewis and co. pp. 317-320.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Groome, Francis, Hindes (1895). "Dumfries". Ordnance gazetteer of Scotland : a survey of Scottish topography, statistical, biographical, and historical. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T.C. Jack. pp. 390-397.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dumfries Saints Rugby Club, Rugby Scotland". Dumfriessaintsrugby.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Tour of Britain, ITV4, 7 pm Sun 11 September 2011

- "David Keswick Athletic Centre". Runtrackdir.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Douglas A. Rathburn (14 July 2011). "Blades of the World: British Rowing Clubs". Oarspotter.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "rowing news and articles – Dumfries and Galloway Standard". Dgstandard.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Archived 20 May 2001 at the Wayback Machine

- "SBA district 17". BowlsClub.org. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Domain Error". Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- "Dumfries and Galloway Cycling Group CTC Section Southwest Scotland, homepage". Dandgcycling.care4free.net. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Cycling holidays in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland". Visitdumfriesandgalloway.co.uk. 30 September 2003. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Rinaldi, Giancarlo (21 November 2013). "The Dumfries 'super school' project that never took off". BBC News.

- Scottish Government (20 August 2007). "Support for Crichton and South of Scotland".

- "Crichton University Campus Dumfries – Scotland UK". Crichtoncampus.co.uk. 11 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "University of Glasgow :: Dumfries Campus :: Primary Education with Teaching Qualification". 3 May 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008.

- "Alive 107.3". media.info.

- "icDumfries – Dumfries & Galloway Standard News". Icdumfries.icnetwork.co.uk. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Dumfries Courier – Regionwide news from your weekly newspaper". Dumfriescourier.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Associates, RJ Design. "Locharbriggs Red Sandstone Suppliers".

- "Dumfries Travel Guide". Scottishholidays.net. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- David Lockwood (16 December 2010). "John Paul Jones a brief biography". Jpj.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Kagyu Samye Ling Monastery and Tibetan Centre". Samyeling.org. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy – Great Eastern". Atlantic-cable.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Cable And Wireless Adventurer Trimaran Diesel Powered Jock Wishart Jules Verne Trophy Record Nigel Irens Boat Design". Solarnavigator.net. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "MiniWeb: Schools Services – Secondary Schools – Dumfries Academy". Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ""Queens legends" on the official Queen of the South FC website". Qosfc.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "QosFC: Jimmy McIntosh". Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "QosFC: Dominic Matteo autobiography review". Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "QosFC: Barry Nicholson". Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "Connections between Dumfries and Blackburn Rovers in the Queen of the South profile on Jackie Oakes". Qosfc.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "QosFC: Allan McNish (part 2)". Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "QosFC: Andrew Coltart". Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "QosFC: Stephen Jardine". Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "Hunter Davies memories of Dumfries in the profile on Billy Houliston". Qosfc.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Life of David Haggart who was executed at Edinburgh, 18 July 1821 for the murder of the Dumfries jailor, National Library of Scotland. Retrieved: 25 July 2019.

- Broadside entitled 'Riot at Dumfries! Hares Arrival' National Library of Scotland. Retrieved: 25 July 2019.

- Charles Altamont Doyle, The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia. Retrieved: 25 July 2019.

- "Dumfries, IA - Dumfries, Iowa Map & Directions - MapQuest". www.mapquest.com.

- "Dumfries, Cat Island, The Bahamas: Maps". www.maphill.com.

- "Dumfries, Carriacou, Grenada: Maps". www.maphill.com.

- McCONKIE, ROCHELLE. "Moyer to travel to Annapolis' sister cities in Europe". baltimoresun.com.

- "Dumfries | Stadt Gifhorn". www.stadt-gifhorn.de.

- Liptrott, Sharon (30 July 2009). "Italian connection to Dumfries". Daily Record.

External links

- James Norie senior

- Dumfries and Galloway Council Website

- www.loreburne.co.uk A Guide to .....Dumfries

- Dumfries and Galloway Museums Archived 22 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- National Library of Scotland: Scottish Screen Archive—selection of archive films about Dumfries

- Dumfries Civil Parish Historical Tax Rolls in Dumfriesshire

- Video footage and history of Dumfries railway station

- Video and history of the Burns Mausoleum, Dumfries.

- Things To See and Do & Attractions in Dumfries

- Life of David Haggart who was executed at Edinburgh, 18 July 1821 for the murder of the Dumfries jailor - Murders - Chapbooks printed in Scotland - National Library of Scotland

- Charles Altamont Doyle - The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia

- County Hotel, 79 High Street, Dumfries, Dumfries, Dumfries and Galloway

.jpg.webp)