Cumbria

Cumbria (/ˈkʌmbriə/ KUM-bree-ə) is a ceremonial county in North West England. It borders the Scottish council areas of Dumfries and Galloway and Scottish Borders to the north, Northumberland and County Durham to the east, North Yorkshire to the south-east, Lancashire to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. Its largest settlement is the city of Carlisle.

Cumbria | |

|---|---|

Location of Cumbria within England | |

| Coordinates: 54°30′N 3°15′W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | North West England |

| Established | 1 April 1974 |

| Established by | Local Government Act 1972 |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (British Summer Time) |

| Members of Parliament | 6 MPs |

| Police | Cumbria Constabulary |

| Largest city | Carlisle |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Lord Lieutenant | Claire Hensman |

| High Sheriff | Samantha Scott[1] |

| Area | 6,767 km2 (2,613 sq mi) |

| • Ranked | 3rd of 48 |

| Population (2021) | 498,888 |

| • Ranked | 41st of 48 |

| Density | 74/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | 2021 census[2] |

| Districts | |

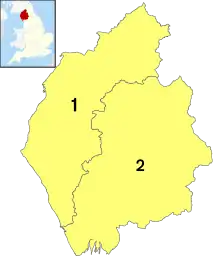

Districts of Cumbria Unitary | |

| Districts | |

The county is predominantly rural, with an area of 6,769 km2 (2,614 sq mi) and a population of 500,012; this makes it the third largest ceremonial county in England by area but the eighth-smallest by population. After Carlisle (74,281), the largest settlements are Barrow-in-Furness (56,745), Kendal (29,593), and Whitehaven (23,986). The county contains two districts, Westmorland and Furness and Cumberland, which are both unitary areas.[3]

Cumbria is well-known for its natural beauty and much of its landscape is protected; the county contains the Lake District National Park and Solway Coast AONB, and parts of the Yorkshire Dales National Park, Arnside and Silverdale AONB, and North Pennines AONB. Together these protect the county's mountains, lakes, and coastline, including Scafell Pike, at 3,209 feet (978 m) England's highest mountain, and Windermere, its largest lake by volume.

The county contains several Neolithic monuments, such as Mayburgh Henge. The region was on the border of Roman Britain, and Hadrian's Wall runs through the north of the county. In the Early Middle Ages parts of the region successively belonged to Rheged, Northumbria, and Strathclyde, and there was also a Viking presence. It became the border between England and Scotland, and was unsettled until the Union of the Crowns in 1603. During the Industrial Revolution mining took place on the Cumberland coalfield and Barrow-in-Furness became a shipbuilding centre, but the county was not heavily industrialised and the Lake District became valued for its sublime and picturesque qualities, notably by the Lake Poets.

In 1974 Cumbria was created from the historic counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, the Furness area of Lancashire, and a small part of Yorkshire, and was a non-metropolitan county (with a county council) until 31 March 2023, when governance was taken up by Cumberland and Westmorland and Furness.

Name

The place names Cumbria and Cumberland both mean "land of the Cumbrians" and are names derived from the term that had been used by the inhabitants of the area to describe themselves. In the period c. 400 – c. 1100, it is likely that any group of people living in Britain who identified as ‘Britons’ called themselves by a name similar to ‘Cum-ri’ which means "fellow countrymen" (and has also survived in the Welsh name for Wales which is Cymru).[4] The first datable record of the place name as Cumberland is from an entry in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle for the year AD 945.[5] This record refers to a kingdom known to the Anglo Saxons as Cumberland (often also known as Strathclyde) which in the 10th century may have stretched from Loch Lomond to Leeds.[6] The first king to be unequivocally described as king of the Cumbrians is Owain ap Dyfnwal who ruled from c. 915 – c. 937.[7]

History

Cumbria was created in April 1974 through an amalgamation of the administrative counties of Cumberland and Westmorland, to which parts of Lancashire (the area known as Lancashire North of the Sands) and of the West Riding of Yorkshire were added.[8]

During the Neolithic period the area contained an important centre of stone axe production (the so-called Langdale axe factory), products of which have been found across Great Britain.[9] During this period stone circles and henges were built across the county and today 'Cumbria has one of the largest number of preserved field monuments in England'.[10]

While not part of the region conquered in the Romans' initial conquest of Britain in AD 43, most of modern-day Cumbria was later conquered in response to a revolt deposing the Roman-aligned ruler of the Brigantes in AD 69.[11] The Romans built a number of fortifications in the area during their occupation, the most famous being UNESCO World Heritage Site Hadrian's Wall which passes through northern Cumbria.[12]

At the end of the period of British history known as Roman Britain (c. AD 410) the inhabitants of Cumbria were Cumbric-speaking native Romano-Britons who were probably descendants of the Brigantes and Carvetii (sometimes considered to be a sub-tribe of the Brigantes) that the Roman Empire had conquered in about AD 85. Based on inscriptional evidence from the area, the Roman civitas of the Carvetii seems to have covered portions of Cumbria. The names Cumbria, Cymru (the native Welsh name for Wales), Cambria, and Cumberland are derived from the name these people gave themselves, *kombroges in Common Brittonic, which originally meant "compatriots".[13][14]

Although Cumbria was previously believed to have formed the core of the Early Middle Ages Brittonic kingdom of Rheged, more recent discoveries near Galloway appear to contradict this.[15] For the rest of the first millennium, Cumbria was contested by several entities who warred over the area, including the Brythonic Celtic Kingdom of Strathclyde and the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria. Most of modern-day Cumbria was a principality in the Kingdom of Scotland at the time of the Norman conquest of England in 1066 and thus was excluded from the Domesday Book survey of 1086. In 1092 the region was invaded by William II and incorporated into England.[16] Nevertheless, the region was dominated by the many Anglo-Scottish Wars of the latter Middle Ages and early modern period and the associated Border Reivers who exploited the dynamic political situation of the region.[17] There were at least three sieges of Carlisle fought between England and Scotland, and two further sieges during the Jacobite risings.

After the Jacobite Risings of the 18th century, Cumbria became a more stable place and, as in the rest of Northern England, the Industrial Revolution caused a large growth in urban populations. In particular, the west coast towns of Workington, Millom and Barrow-in-Furness saw large iron and steel mills develop, with Barrow also developing a significant shipbuilding industry.[18] Kendal, Keswick and Carlisle all became mill towns, with textiles, pencils and biscuits among the products manufactured in the region. The early 19th century saw the county gain fame when the Lake Poets and other artists of the Romantic movement, such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, lived among, and were inspired by, the lakes and mountains of the region. Later, the children's writer Beatrix Potter also wrote in the region and became a major landowner, granting much of her property to the National Trust on her death.[19] In turn, the large amount of land owned by the National Trust assisted in the formation in 1951 of the Lake District National Park, which remains the largest National Park in England and has come to dominate the identity and economy of the county.

The Windscale fire of 10 October 1957 was the worst nuclear accident in Great Britain's history.[20]

Cumbria was created in 1974 from the traditional counties of Cumberland and Westmorland, the Cumberland County Borough of Carlisle, along with the North Lonsdale or Furness part of Lancashire, usually referred to as "Lancashire North of the Sands", (including the county borough of Barrow-in-Furness) and, from the West Riding of Yorkshire, the Sedbergh Rural District.[8] Between 1974 and 2023 it was governed by Cumbria County Council but in 2023 the county council was abolished and replaced by Cumberland and Westmorland and Furness.

On 2 June 2010, taxi driver Derrick Bird killed 12 people and injured 11 others in a shooting spree that spanned over 24 kilometres (15 mi) along the Cumbrian coastline.[21]

Local newspapers The Westmorland Gazette and Cumberland and Westmorland Herald continue to use the name of their historic counties. Other publications, such as local government promotional material, describe the area as "Cumbria", as does the Lake District National Park Authority.

Geography

Cumbria is the most northwesterly ceremonial county of England. Most of Cumbria is mountainous, with the majority of the county being situated in the Lake District while the Pennines, consisting of the Yorkshire Dales and the North Pennines, lie at the eastern and south-east areas of the county. At 978 metres (3,209 ft) Scafell Pike is the highest point in Cumbria and in England. Windermere is the largest natural lake in England.

The Lancaster Canal runs from Preston into southern Cumbria and is partly in use. The Ulverston Canal which once reached to Morecambe Bay is maintained although it was closed in 1945. The Solway Coast and Arnside and Silverdale AONB's lie in the lowland areas of the county, to the north and south respectively.

Boundaries and divisions

The northernmost and southernmost points in Cumbria are just west of Deadwater, Northumberland and South Walney respectively. Kirkby Stephen (close to Tan Hill, North Yorkshire) and St Bees Head are the most easterly and westerly points of the county. The boundaries are along the Irish Sea to Morecambe Bay in the west, and along the Pennines to the east. Cumbria's northern boundary stretches from the Solway Firth from the Solway Plain eastward along the border with Scotland.

Cumbria is bordered by Northumberland, County Durham, North Yorkshire, Lancashire in England, and Dumfries and Roxburgh, Ettrick and Lauderdale in Scotland.

Economy

Many large companies and organisations are based in Cumbria. The county council itself employs around 17,000 individuals, while the largest private employer in Cumbria, the Sellafield nuclear processing site, has a workforce of 10,000.[22] Below is a list of some of the county's largest companies and employers (excluding services such as Cumbria Constabulary, Cumbria Fire and Rescue and the NHS in Cumbria), categorised by district.

Tourism

The largest and most widespread industry in Cumbria is tourism. The Lake District National Park alone receives some 15.8 million visitors every year.[23] Despite this, fewer than 50,000 people reside permanently within the Lake District: mostly in Ambleside, Bowness-on-Windermere, Coniston, Keswick, Gosforth, Grasmere and Windermere.[23] Over 36,000 Cumbrians are employed in the tourism industry which adds £1.1 billion a year to the county's economy. The Lake District and county as a whole attract visitors from across the UK,[23] Europe, North America and the Far East (particularly Japan).[23] The tables below show the twenty most-visited attractions in Cumbria in 2009. (Not all visitor attractions provided data to Cumbria Tourism who collated the list. Notable examples are Furness Abbey, the Lakes Aquarium and South Lakes Safari Zoo, the last of which would almost certainly rank within the top five).[24]

|

|

Economic output

This is a chart of the trend of regional gross value added (GVA) of East and West Cumbria at current basic prices published (pp. 240–253) by the Office for National Statistics

| Year | East Cumbria | West Cumbria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional GVA[26] | Agriculture[27] | Industry[28] | Services[29] | Regional GVA[26] | Agriculture[27] | Industry[28] | Services[29] | |

| 1995 | 2,679 | 148 | 902 | 1,629 | 2,246 | 63 | 1,294 | 888 |

| 2000 | 2,843 | 120 | 809 | 1,914 | 2,415 | 53 | 1,212 | 1,150 |

| 2003 | 3,388 | 129 | 924 | 2,335 | 2,870 | 60 | 1,420 | 1,390 |

Politics

Local

Between 1974 and 2023 Cumbria was administered by Cumbria County Council and six district councils: Allerdale, Barrow-in-Furness, Carlisle, Copeland, Eden, and South Lakeland.

In July 2021 the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government announced that, on 1 April 2023, the administrative county will be reorganised into two unitary authorities: one to be known as Cumberland, and the other as Westmorland and Furness. Cumbria County Council and the six districts are to be abolished and their functions transferred to the new authorities.[30] The two new unitary authorities will continue to constitute a ceremonial county named "Cumbria" for the purpose of lieutenancy and shrievalties, being presided over by a Lord Lieutenant of Cumbria and a High Sheriff of Cumbria.[31][32]

Cumberland

Cumberland, covers the former districts of Allerdale, Carlisle, and Copeland.[33] The territory constitutes most of the historic county of Cumberland. Its largest settlement is Carlisle. It excludes Alston and Penrith within the historic boundaries of Cumberland.

Westmorland and Furness

Westmorland and Furness, covers the former districts of Barrow-in-Furness, Eden, and South Lakeland.[33] The territory includes all of the historic county of Westmorland and neighbouring areas historically in Lancashire and Yorkshire. Its largest settlement is Barrow-in-Furness.

National

At the 2019 general election, no Labour Members of Parliament (MPs) were elected, the first time since 1910.

| Constituency | 1983 | 1987 | 1992 | 1997 | 2001 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrow and Furness | CON Cecil Franks | LAB John Hutton | LAB John Woodcock | CON Simon Fell | ||||||

| Carlisle | LAB Ronald Lewis | LAB Eric Martlew | CON John Stevenson | |||||||

| Copeland | LAB Jack Cunningham | LAB Jamie Reed | CON Trudy Harrison | |||||||

| Penrith and The Border | CON David Maclean | CON Rory Stewart | CON Neil Hudson | |||||||

| Westmorland and Lonsdale | CON Michael Jopling | CON Tim Collins | LD Tim Farron | |||||||

| Workington | LAB Dale Campbell-Savours | LAB Tony Cunningham | LAB Sue Hayman | CON Mark Jenkinson | ||||||

| 2019 General Election Results in Cumbria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Change from 2017 | Seats | Change from 2017 | ||||

| Conservative | 143,615 | 52.4% | 5 | ||||||

| Labour | 79,402 | 28.9% | 0 | ||||||

| Liberal Democrats | 39,426 | 14.4% | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Greens | 4,223 | 1.5% | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Brexit | 3,867 | 1.4% | new | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Others | 3,044 | 1.1% | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Total | 274,313 | 100.0 | 6 | ||||||

Education

Although Cumbria has a comprehensive system almost fully, there is one state grammar school in Penrith. There are 42 state secondary schools and 10 independent schools. The more rural secondary schools tend to have sixth forms (although in Barrow-in-Furness district, no schools have sixth forms due to the only sixth college in Cumbria being located in the town) and this is the same for three schools in Allerdale and South Lakeland, and one in the other districts. Chetwynde is also the only school in Barrow to educate children from nursery all the way to year 11.

Colleges of further education in Cumbria include:

- Carlisle College

- Furness College which includes Barrow Sixth Form College

- Kendal College

- Lakes College

The University of Cumbria is one of the UK's newest universities, having been established in 2007. It is at present the only university in Cumbria and has campuses across the county, together with Lancaster and London.

Transport

Road

The M6 is the only motorway that runs through Cumbria. Kendal and Penrith are amongst its primary destinations. Further north it becomes the A74(M) at the border with Scotland north of Carlisle. Major A roads within Cumbria include:

Several bus companies run services in Cumbria serving the main towns and villages in the county, with some services running to neighbouring areas such as Lancaster. Stagecoach North West is the largest; it has depots in Barrow-in-Furness, Carlisle, Kendal and Workington. Stagecoach's flagship X6 route connects Barrow-in-Furness and Kendal in south Cumbria.

Ports

There are only two airports in the county: Carlisle Lake District and Barrow/Walney Island. Both airports formerly served scheduled passenger flights and both are proposing expansions and renovations to handle domestic and European flights in the near future. The nearest international airports to south Cumbria are Blackpool, Manchester, Liverpool John Lennon and Teesside. North Cumbria is closer to Newcastle, Glasgow Prestwick and Glasgow International.

Barrow-in-Furness is one of the country's largest shipbuilding centres, but the Port of Barrow is only minor, operated by Associated British Ports alongside the Port of Silloth in Allerdale. There are no ferry links from any port or harbour along the Cumbria coast.

Rail

The busiest railway stations in Cumbria are Carlisle, Barrow-in-Furness, Penrith and Oxenholme Lake District. The 399 miles (642 km) West Coast Main Line runs through the Cumbria countryside, adjacent to the M6 motorway. The Cumbrian Coast Line connects Barrow-in-Furness to Carlisle and is a vital link in the west of the county. Other railways in Cumbria are the Windermere Branch Line, most of the Furness Line and much of the Settle-Carlisle Railway.

Demography

Cumbria's largest settlement and only city is Carlisle, in the north of the county. The largest town, Barrow-in-Furness, in the south, is slightly smaller. The county's population is largely rural: it has the second-lowest population density among English counties, and has only five towns with a population of over 20,000. Cumbria is also one of the country's most ethnically homogeneous counties, with 95.1% of the population categorised as White British (around 470,900 of the 495,000 Cumbrians).[34] However, the larger towns have ethnic makeups that are closer to the national average. The 2001 census indicated that Christianity was the religion with the most adherents in the county.

2010 ONS estimates placed the number of foreign-born (non-United Kingdom) people living in Cumbria at around 14,000 and foreign nationals at 6,000.[35] The 2001 UK Census showed the following most common countries of birth for residents of Cumbria that year:

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-1974 statistics were gathered from local government areas that are now comprised by Cumbria Source: Great Britain Historical GIS.[36][37] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Settlements

- Alston

- Ambleside

- Appleby-in-Westmorland

- Arlecdon and Frizington

- Askam and Ireleth

- Aspatria

- Bowness-on-Windermere

- Brampton

- Cleator Moor

- Cockermouth

- Coniston

- Dalston

- Dalton-in-Furness

- Egremont

- Grasmere

- Harrington

- Hawkshead

- Keswick

- Kirkby Lonsdale

- Kirkby Stephen

- Kirkoswald

- Longtown

- Maryport

- Millom

- Milnthorpe

- Sedbergh

- Shap

- Silloth

- St Bees

- Ulverston

- Walney Island

- Whitehaven

- Wigton

- Windermere

- Workington

Sport

Running

Fell running is a popular sport in Cumbria, with an active calendar of competitions taking place throughout the year. Cumbria is also home to several of the most active orienteering clubs in the UK as well as the Lakes 5 Days competition that takes place every four years.

Football codes

Workington is home to the ball game known as Uppies and Downies,[38] a traditional version of football, with its origins in medieval football or an even earlier form.[39] Players from outside Workington also take part, especially fellow West Cumbrians from Whitehaven and Maryport.[40]

Cumbria formerly had minor American football clubs, the Furness Phantoms (the club is now defunct, its last name was Morecambe Bay Storm) and the Carlisle Kestrels.[41]

Association

Barrow and Carlisle United are the only professional football teams in Cumbria. Carlisle United attract support from across Cumbria and beyond, with many Cumbrian "ex-pats" travelling to see their games, both home and away.

Workington—who are always known locally as "the reds"—are a well-supported non-league team, having been relegated from the Football League in the 1970s. Workington made a rapid rise up the non league ladder and in 2007/08 competed with Barrow in the Conference North. Barrow were then promoted to the Conference Premier in 2007/08. In 2020, Barrow were promoted to the Football League as a result of winning the National League.

Rugby codes

Rugby union is popular in the county's north and east with teams such as Furness RUFC & Hawcoat Park RUFC (South Cumbria), Workington RUFC (Workington Zebras), Whitehaven RUFC, Carlisle RUFC, Creighton RUFC, Aspatria RUFC, Wigton RUFC, Kendal RUFC, Kirkby Lonsdale RUFC, Keswick RUFC, Cockermouth RUFC, Upper Eden RUFC and Penrith RUFC.

Rugby league is a very popular sport in south and West Cumbria. Barrow, Whitehaven and Workington play in the Rugby League Championships. Amateur teams; Wath Brow Hornets, Askam, Egremont Rangers, Kells, Barrow Island, Hensingham and Millom play in the National Conference.

Bat-and-ball

Cumbria County Cricket Club is one of the cricket clubs that constitute the National Counties in the English domestic cricket structure. The club, based in Carlisle, competes in the National Counties Cricket Championship and the NCCA Knockout Trophy. The club also play some home matches in Workington, as well as other locations. Cumbrian club cricket teams play in the North Lancashire and Cumbria League.

Cumbria is home to the Cartmel Valley Lions, an amateur baseball team based in Cartmel.

Wrestling

Cumberland and Westmorland wrestling is an ancient and well-practised tradition in the county with a strong resemblance to Scottish Backhold.

In the 21st century Cumberland and Westmorland wrestling along with other aspects of Lakeland culture are practised at the Grasmere Sports and Show, an annual meeting held every year since 1852 on the August Bank Holiday.

The origin of this form of wrestling is a matter of debate, with some describing it as having evolved from Norse wrestling brought over by Viking invaders,[42] while other historians associate it with the Cornish and Gouren styles[43] indicating that it may have developed out of a longer-standing Celtic tradition.[44]

Racing

Cumbria Kart Racing Club is based at the Lakeland Circuit, Rowrah, between Cockermouth and Egremont Lakeland Circuit. The track is currently a venue for rounds of both major UK national karting championships About Cumbria Kart Racing Club. Formula One world champions Lewis Hamilton and Jenson Button both raced karts at Rowrah many times in the formative stages of their motor sport careers,[45] while other F1 drivers, past and present, to have competed there include Johnny Herbert, Anthony Davidson, Allan McNish, Ralph Firman, Paul di Resta and David Coulthard, who hailed from just over the nearby Anglo-Scottish border and regarded Rowrah as his home circuit, becoming Cumbria Kart Racing Club Champion in 1985 in succession to McNish (di Resta also taking the CKRC title subsequently).[46]

Workington Comets were a Workington-based professional speedway team,[47] which competed in the British Speedway Championship.[48]

Food

Cumbria is the UK county with the highest number of Michelin-starred restaurants, with seven in this classification in the Great Britain and Ireland Michelin Guide of 2021. Traditional Cumbrian cuisine has been influenced by the spices and molasses that were imported into Whitehaven in the 18th century. The Cumberland sausage (which has a protected geographical status) is a well-recognised result of this. Other regional specialities include Herdwick mutton and the salt-marsh raised lamb of the Cartmel Peninsula.[49]

Dialect influences

Celtic

- Cumbria was Celtic speaking until the Viking invasion, if not later (Cymry)[50]

- Little English spoken in Cumbria; relatively sparsely populated until 12th/13th centuries[51]

- The invading Angles and Saxons forced the indigenous Celtic peoples back to the western highlands of Cumbria, Wales and Cornwall, with little linguistic consequence, apart from a residual scattering of place-names.

- Northwest – possibility of direct influence from Irish Gaelic across Irish Sea via Whitehaven until 10th century[52]

- Celtic influence/kingdoms may have confirmed perception of difference between the north–south[50]

- Linguistic interaction between Celts and English underrated: effectively Celtic influence marked the beginnings of a linguistic divide between English and other West Germanic dialects.[53]

- Lexis – Celtic influence left specifically on the sound pattern of sheep-scoring numerals of Cumbrian and West Yorkshire[50]

- Loss of inflections may be explained by contact with Celtic tribes and inter-marriage.[50]

Anglo-Saxon/Viking

- Earliest Anglo-Saxon settlements in the east of England. Took over 200 years to establish a frontier in the west where the displaced British had settled[54]

- Morphology – Old Northumbrian (little evidence) signs of loss of inflexions long before southern dialects below the Humber, precede Viking settlements and dialect contact situation[50]

Scandinavian/Norse/Dane

- Lack of extent of Old English written evidence[50]

- Main attacks/raids on the North-East coast at Lindisfarne and Jarrow in 793/ 794[50]

- Settlement patterns (Danes) contributed to emerging differences over time between Northumberland. Durham and Yorkshire dialects [50]

- Norwegian settlers via Ireland to Isle of Man, Mersey estuary (901) and the Cumbrian/ Lancashire coasts (900-50) – dialectal differences (Danes/ Norwegians) often lumped together in standard histories – MUST have confirmed emerging dialectal differences east and west of the Pennines[50]

- Danelaw – land of north and east of land ruled under Danish law and Danish customs (978-1016) [50]

- Scandinavian influences vocabulary – common words gradually diffused/ entered word stock (borrowings) which survive in regional use – ‘fell’ hillside, ‘lug’ ear, ‘loup’ jump, ‘aye’ yes

- Influence on grammatical structure - Middle English texts reveal that present participle form ‘-and’, and possible that use of ‘at’ and ‘as’ as relative pronouns from Cumbria to East Yorkshire[50]

- phonetically /g/, /k/ and cluster /sk/ have a northern/ Norse pronunciation /j/, /ʧ/ and /ʃ/ which are West Saxon – hard vs. soft consonants of north–south dialects – e.g. ‘give/ rigg’ ridge, ‘skrike’ shriek, ‘kist’ chest and ‘ik’[50]

- ‘Interdialect forms’ in Danelaw area (diffuse > focussed situation) - no clear idea about what language they were speaking – mixture of Old English and Norse e.g. ‘she’ (3rd person pronoun) is claimed by both languages[50][55]

- ‘Bilingualism was norm in areas under Danelaw (plausible)[50]

- Norse runic inscriptions survive from 11th century in Cumbria – therefore may only been after Norman Conquest that ‘Norse as a living language died out’[56]

- Norse surviving longest in closed communities, as in the Lake District[57]

Normans

Cumbric

- Early 10th century – all of the northwest of England occupied by a mixture of newcomers from Ireland of mixed Viking and Gaelic ancestry. The grip from Northumbrian on the former territory of Rheged was that of Britons of Strathcylde reoccupied southwest Scotland and northwest England as far south as Derwent and Penrith.[59] which was held until Carlisle retaken by Scots in 1136[50]

- Cumbric perhaps survived until it faded in the early 12th century throughout Cumbria.[60]

- Cumbric score – counting sheep – Welsh correspondence Welsh ("un, dau, tri") – Cumberland ("yan, tyan, tethera") – Westmorland ("yan, than, teddera") – Lancashire ("yan, taen, tedderte") – West Yorkshire ("yain, tain, eddero") [59] – survived 7-8 centuries after the language itself had died – Brittonic origin

- Not one single complete phrase in Cumbric survives, evidence to suggest strong literary tradition, probably oral, some of this early material is known in a Welsh version[59]

Media

Two evening newspapers are published daily in Cumbria. The News and Star focuses largely on Carlisle and the surrounding areas of north and west Cumbria, and the North-West Evening Mail is based in Barrow-in-Furness and covers news from across Furness and the South Lakes. The Cumberland and Westmorland Herald and The Westmorland Gazette are weekly newspapers based in Penrith and Kendal respectively. The Egremont 2Day newspaper, formerly Egremont Today when affiliated with the Labour Party, was a prominent monthly publication - founded by Peter Watson (and edited by him until his death in 2014) in 1990 until July 2018. In February 2020 The Herdwick News, run by the last editor of The Egremont 2Day, was launched and is an independent online news publication covering the county of Cumbria and the North West.

Due to the size of Cumbria the county spans two television zones: BBC North East and Cumbria and ITV Border in the north and BBC North West and ITV Granada in the south. Heart North West, Greatest Hits Radio Cumbria & South West Scotland and Smooth Lake District are the most popular local radio stations throughout the county, with BBC Radio Cumbria being the only station that is aimed at Cumbria as a whole.

The Australian-New Zealand feature film The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey (1988) is set in Cumbria during the onset of the Black Death in 14th-century Europe.

Cumbria is host to a number of festivals, including Kendal Calling (actually held in Penrith since 2009)[61][62] and Kendal Mountain Festival.

Places of interest

| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Places of Worship | |

| Museum (free/not free) | |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

Notable people

- Abraham Acton

- Adam Roynon

- Ade Gardner

- Aim

- Alfred Wainwright

- Anna Dean

- Anna Ford

- Beatrix Potter

- Ben Stokes

- Bill Birkett

- Brad Kavanagh

- Brian Donnelly

- British Sea Power

- Catherine Hall (novelist)

- Catherine Parr

- Chris Bonington

- Christine McVie

- Christopher Wordsworth

- Constance Spry

- Baron Campbell-Savours

- Dean Henderson

- Derrick Bird

- Dick Huddart

- Donald Campbell

- Dorothy Wordsworth

- Douglas Ferreira

- Eddie Stobart

- Edmund Grindal

- Edward Stobart

- Edward Troughton

- Emlyn Hughes

- Eric Robson

- Eric Wallace

- Fletcher Christian

- Francis Dunnery

- Francis Howgill

- Frank McPherson

- Baron Peart

- Gary McKee

- Gary Stevens

- Gavin Skelton

- George MacDonald Fraser

- George Romney

- Georgia Stanway

- Glenn Cornick

- Glenn Murray

- Harry Hadley

- Helen Skelton

- Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale

- Ian McDonald

- Ike Southward

- Jack Pelter

- James Alexander Smith

- Jess Gillam

- Jimmy Lewthwaite

- Jack Adams

- John Burridge

- John Dalton

- John Peel

- John Ruskin

- John Wilkinson

- Jon Roper

- Josefina de Vasconcellos

- Joss Naylor

- Karen Taylor

- Kathleen Ferrier

- Keith Tyson

- Kyle Dempsey

- Lady Anne Clifford

- Len Wilkinson

- Lord Soulsby

- Malcolm Wilson

- Margaret Fell

- Mark Cueto

- Mark Jenkinson

- Matthew Wilson

- Maurice Flitcroft

- Melvyn Bragg

- Montagu Slater

- Neil Ferguson

- Nella Last

- Nigel Kneale

- Norman Birkett

- Norman Gifford

- Norman Nicholson

- Percy Kelly

- Peter Purves

- Phil Jackson

- Richard Abbot

- Richard T. Slone

- Robert Southey

- Saint Ninian

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- Sarah Hall

- Sheila Fell

- Sir James Ramsden

- Sir John Barrow

- Sol Roper

- Stan Laurel

- Dame Stella Rimington

- Stephen Holgate

- Steve Dixon

- Stuart Lancaster

- Stuart Stockdale

- Dave Myers

- Thomas Cape

- Thomas DeQuincey

- Thomas Henry Ismay

- Thomas Round

- Troy Donockley

- Vic Metcalfe

- Wayne Curtis

- William Gilpin

- William Stobart

- William Whitelaw

- William Wordsworth

- Willie Horne

See also

- Anglo-Scottish border

- Cumbria Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner

- Cumbria shootings

- Cumbrian dialect

- Cumbrian toponymy

- Cumbric language

- Etymology of Cumbrian place names

- Healthcare in Cumbria

- List of Cumbria-related topics

- List of High Sheriffs of Cumbria

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Cumbria

- Outline of England

- Rose Castle

References

- "No. 62943". The London Gazette. 13 March 2020. p. 5161.

- UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – Cumbria County (E10000006)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "Names for two controversial Cumbria councils revealed". BBC News. 5 November 2021. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- Tim (30 July 2011). "Terminology topics 5: Cumbria". Senchus. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- "Cumberland :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- Molyneaux, George (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century (First ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1. OCLC 898531165.

- Phythian-Adams, Charles (1996). Land of the Cumbrians : a study in British provincial origins, A.D. 400-1120. Aldershot, England: Scolar Press. ISBN 1-85928-327-6. OCLC 35012254.

- "Local Government Act 1972". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Castleden, Rodney (1992). Neolithic Britain: New Stone Age Sites of England, Scotland, and Wales. Routledge. ISBN 9780415058452. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Barrowclough (2010), p. 105.

- Shotter (2014), p.5

- "Frontiers of the Roman Empire". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Cymric". Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 April 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Davies, John (2007) [1990]. A History of Wales. Penguin Books. pp. 68–69.

- Ronan, Toolis (31 January 2017). The lost Dark Age kingdom of Rheged : the discovery of a royal stronghold at Trusty's Hill, Galloway. Bowles, Christopher R. Oxford. ISBN 9781785703126. OCLC 967457029.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sharpe, Richard (2006). Norman rule in Cumbria, 1092-1136. Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. ISBN 978-1873124437. OCLC 122952827.

- Tuck, J.A. (January 1986). "The Emergence of a Northern Nobility, 1250–1400". Northern History. 22 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1179/007817286790616516. ISSN 0078-172X.

- Gill, Jepson (15 November 2017). Barrow-in-Furness at work : people and industries through the years. Stroud. ISBN 9781445670041. OCLC 1019605931.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sarah, Gristwood (9 June 2016). The story of Beatrix Potter. London. ISBN 9781909881808. OCLC 951610299.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richard Black (18 March 2011). "Fukushima - disaster or distraction?". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Fresco, Adam (2 June 2010). "Police identify man wanted over drive-by shootings in Cumbria". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- "Cumbrian employers supporting staff after multiple shooting". Personneltoday. 3 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- "Lake District National Park". Lake District National Park. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- "Lake District National Park". Cumbria Tourism. Archived from the original on 2 August 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- "About Us - Lake District Wildlife Park". Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

- includes hunting and forestry

- includes energy and construction

- includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

- "Next steps for new unitary councils in Cumbria, North Yorkshire and Somerset". GOV.UK. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- "The Cumbria (Structural Changes) Order 2022: Lords-Lieutenant". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- "The Cumbria (Structural Changes) Order 2022: Sherrifs". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- "Local Government Reorganisation. Delivering Two New Councils for Cumbria". Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- "Current Estimates – Population Estimates by Ethnic Group Mid-2009 (experimental)". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- "Table 1.3: Estimated population resident in the United Kingdom, by foreign country of birth, April 2009 to March 2010". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- A Vision of Britain through time, Cumbria Modern (post 1974) County: Total Population, archived from the original on 6 September 2011, retrieved 10 January 2010

- "Ballet star shows off charity portraits". Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- "Uppies and Downies website". Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Henricks, Thomas S. (1991). Origins of Mass ball Games. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313274534. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Times and Star". Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Carlisle Kestrels American Football team hoping to soar again". News & Star. 17 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Kronos; A Chronology of the Martial Arts and Combative Sports". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- "Amateur Wrestling". Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- "Kronos; A Chronology of the Martial Arts and Combative Sports". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- "About Cumbria Kart Racing Club". 21 April 2012. Archived from the original on 21 April 2012.

- "Rowrah Paves Way for Next Lewis Hamilton". Ergemont Today. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- "Workington Speedway". Workington Comets. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "British Speedway's Premier League". British Speedway. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "Cumbria - the UK county with the most Michelin stars". Michelin Guide. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- Wales, Katie (2006). Northern English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62. ISBN 9780521861076.

- Strang, Barbara M, H (1970). A History of English. London: Methuen. p. 256.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Elmes, Simon (1999). The Routes of English. London: BBC. p. 27.

- Tristram, Hildegard (2000). "Introduction: languages in contact; layer cake model or otherwise?". The Celtic Languages. 2: 1–8.

- Leith, Dick (1983). A Social History of English. London: Routledge. p. 106.

- Trudgill, Peter (1974). "Linguistic change and diffusion: description and explanation in sociolinguistic dialect geography". Language in Society. 3 (2): 215–2246. doi:10.1017/s0047404500004358. S2CID 145148233.

- Werner, Otmar (1991). "The incorporation of Old Norse pronouns in Middle English: suppletion by loan". Language Contact in the British Isles: 369–401. doi:10.1515/9783111678658.369.

- Gordon, E, V (1923). "Scandinavian Influence in Yorkshire Dialects". Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society. 4: 5–22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jewell, Helen (1994). The North-South Divide: The Origins of Northern Consciousness in England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 20.

- Price, G (2000). Languages in Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 125.

- Jackson, Peter (1989). Maps of Meaning: An Introduction to Cultural Geography. London: Unwin Hyman. p. 72.

- "Travel - Kendal Calling". Kendal Calling. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Kendal Calling 2009 - have your say". The Westmorland Gazette. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

External links

Media related to Cumbria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cumbria at Wikimedia Commons Cumbria travel guide from Wikivoyage

Cumbria travel guide from Wikivoyage- Cumbria on Encyclopedia Britannica

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)