Dushmani (tribe)

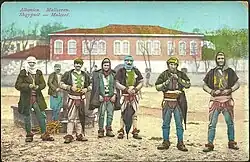

The clan of Dushmani was one of the northern Albanian tribes, living in North Albania up to 20th century.[1] Edith Durham, the person who visited them in the beginning of 20th century described them as one of the most wilder tribes among Albanians.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

| Dushmani | |

|---|---|

Albanians bayraks as of 1918, Dushmani covers section 61. | |

| Current region | North Albania |

History

The term Dushmani may have been recorded in the sixth century by the early Byzantine geographer and scholar Procopius of Caesarea (ca. 500– ca. 565) as Dousmanes who uses this name to refer to a Thracian-Illyrian castle restored by the Emperor Justinian. It occurs with more certainty a millennium later in an Ottoman document as Düşman in 1581, and as Dusimani on the maps of the Venetian cartographer Francesco Maria Coronelli in 1688 and 1691. One is reminded of the Ottoman Turkish (originally Persian) oriental term dushman ‘enemy, foe’, but there does not seem to be any etymological relationship to the word here. Dushmani also occurs as a family name. Edith Durham records a document from 1403 which mentions ‘Goranimus, Damianus and Nenada, brothers Dusmani, Lords of Polati Minor’ who offered themselves as subjects of Venice and swore fidelity on condition that Republic of Venice guarantee them possession of their lands.[3][4][5]

Ethnography

According to Durham, Dushmani consisted in two groups, Dushmani and Temali. They were part of the district of Postripa which consisted of Mazreku, Drishti, Shlaku, and Dushmani. Ecclesiastically the tribe was wholly Christian they were included in the diocese of Pulati. Their name derived from Pal Dushmani, a 15th century Albanian lord and member of the Dushmani family. In the beginning of 20th century the group of Dushmani consisted in 160 houses.

Origin legend

According to the oral traditions of the Dushmani, as recorded by the local vicar David Pepa, two brothers from the Kalia brotherhood left their homeland in Tuzi and settled in northern Albania. One brother settled in Arrë, his descendants then founding or settling the villages of Vilë, Qerret, Telume, Kishë-Arrë, Kllogjen, Kajvall, and Malagji - founding the core of the Dushmani tribe. The second brother, however, migrated eastwards and founded the Thaçi tribe.

Upon settling the area, the Kalia encountered the anas (native) Lumbardhi tribe with whom they eventually fell into conflict with. The oral tradition details that a relative or branch of the Kalia intermarried with the Lumbardhi, the union resulting in the birth of a certain Kurt who came to become extremely influential and powerful in the region. As such, Kurti decided to challenge his uncles from the Lumbardhi and conquer their lands; resulting in the expulsion of the latter tribe into Mirdita. Thus the Kalia came to dominate the region of Dushmani.

The brotherhoods from Vilë and Qerret trace their ancestry back to the ancestral figure of Doç Kalia, those being the: 1) Gjo-Lekaj; 2) Gjo-Gjeçaj; 3) Ndokaj; 4) Bicaj; 5) Gjo-Mêmaj; 6) Çekaj; 7) Gjo-Gjinaj; 5) Lush-Gjinaj; 6) Gjeçaj.

The brotherhoods from Arrë whom descend from the Kalia but cannot trace their ancestry back to a clear ancestral figure from the clan are the: 1) Matanaj; 2) Gjinaj; 3) Garraj; 4) Ulpepaj; 5) Vatgjonaj; 6) Ulnikaj. The Garraj, however, a matrilineal descendants of the Kalia, their patrilineal ancestry being from the regions of Pult or Nikaj.

The Qukaj and Mal-Gjonaj of Telume stem from the ancestral figure of Tetë Kalia. The Dedë-Jakupi of Shkodra also originate from Tetë Kalia.

The brotherhoods descending from Kolë Kalia are the: 1) Geg-Kolaj from Telume; 2) Ndré-Gjeçaj; 3) Nik-Gjeçaj; 4) Rrypaj.

From the figure of Kurti and his descendants, Vas Çeka and Mark Çeka, descend a number of brotherhoods: 1) Vasaj; 2) Ndré-Gjekaj; 3) Mar-Çekaj; 4) Gjeçaj; 5) Ulaj; 6) Lek-Markaj; 7) Hasanaj; 8) Bubaj; 9) Pep-Lekaj; 10) Volaj; 11) Sekuj; 12) Vat-Hysenaj; 13) Gjo-Makaj; 14) Lek-Markaj; 15) Domaj; 16) Lek-Kokaj.[6]

Traditions and customs

The social life of Dushmani was organized following strictly the Code of Lekë Dukagjini. According to Durham "Dushmani believes in Lek Dukaghin as the One-that-must-be-obeyed, and that he ordered blood-vengeance. The teaching of Christ, the laws of the Church, fall on deaf ears when the law of Lek runs counter to them..". The blood vengeance was widespread among Dushmani. At the time of Edith Durham's visit, around forty houses were in blood within the tribe only, while for external bloods, they were countless.

The men of the tribe had the custom of tattooing a tiny cross upon the breast or upper arm, in case that if being found dead in a strange place, they would be certain of Christian burial.

Pagan beliefs were still active and many of the grave-slabs in Dushmani churchyard were rudely scored with mysterious patterns in which the sun and crescent moon almost invariably occurred.[7]

Dialect

The peculiarities of Dushmani dialect were analyzed by linguist Waclaw Cimochowski, in his work "Le dialecte de Dushmani" (Poznan 1951).[8]

References

- Robert Elsie (19 March 2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Scarecrow Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8108-7380-3. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- High Albania Virago/Beacon travelers Volume 768 of Beacon paperback Author Edith Durham Edition reprint, illustrated Publisher Beacon Press, 1987 ISBN 0-8070-7035-1, ISBN 978-0-8070-7035-2 p.164

- Robert, Elsie. The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. p. 167. ISBN 978 1 78453 401 1.

- "Mr. Frederic Durham". BMJ. 2 (3528): 325–325. 1928-08-18. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3528.325. ISSN 0959-8138.

- "Nopcsa von Felsőszilvás, Franz Frh". dx.doi.org. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- Pepa, David (1934). "Fisi i Dushmanit". Hylli i Dritës. 5 (10): 226–30.

- High Albania Virago/Beacon travelers Volume 768 of Beacon paperback Author Edith Durham Edition reprint, illustrated Publisher Beacon Press, 1987 ISBN 0-8070-7035-1, ISBN 978-0-8070-7035-2 p.164-165

- Le dialecte de Dushmani: description de l'un des parlers de l'Albanie du nord Volume 14, Issue 1 of Prace, Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciółl Nauk Komisja Filologiczna Prace Komisji Filologicznej Volume 14 of Prace Komisji Filologicznej - Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk Author Wacław Cimochowski Publisher Nakładem poznańskiego towarzystwa pszyjaciół nauk z zasiłkiem ministerstwa szkół wyższych i nauki, 1951