Dutch–Moroccan War (1775–1777)

The Dutch–Moroccan War (1775–1777), also known as The Moroccan War (1775–1777), was initiated when Moroccan King Mohammed III declared war on the Dutch Republic. This declaration was a response to the Dutch's lack of proper gifts and an accidental attack on a Moroccan ship. However, the Dutch gained a significant advantage during the conflict through effective blockades of Moroccan ports, well-organized patrols against Moroccan ships, the destruction of the king's two best ships, and other great losses for the Moroccans under the leadership of Captains Dedel and Kinsbergen. These factors put the Moroccans in a strong disadvantage, ultimately leading to Mohammed III asking the States General for peace. As part of the treaty, all Dutch slaves held in Moroccan captivity were released without any ransom, and the Dutch were no longer required to bring gifts.[3][14][15][16][17]

| Dutch–Moroccan War (1775–1777) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

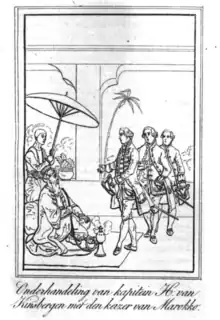

Negotiations of JH van Kinsbergen with the Emperor of Morocco. (19th-century illustration) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 Frigates, 3-4 Xebecs, and 2 rowboats set out to capture specifically Dutch ships[4][5][6] 4 Galiots[7] 1 other frigate[8] Other Moroccan Pirates[9] |

First half of 1775: 8 Warships Second half of 1775, and after: Patrolling, and escorting ships: 8 frigates 1 ship of the line Blocking the coast, and ports of Morocco: 8–12 Warships[10] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

The king's best 2 Frigates destroyed 50 cannons lost best 3 Xebecs destroyed 1 Galiot Severely damaged 1 other Frigate captured 2 rowboats destroyed[11][8][12][7][6] | 2 Merchant ships, and 2 Fluyts attacked but not taken (goods of 2 retaken)[13] | ||||||

Background

On September 14, 1774, the Dutch ship "Princess Royal Frederica Sophia Wilhelmina," under the command of Captain Quirijn Dabenis, reached the shores of the bay near Larache. However, due to the lack of a suitable anchoring spot, the ship had to wait for two days before it could safely drop anchor. The purpose of this voyage was to deliver a gift to the Moroccan king as a token of their strong friendship and enduring alliance. The gift consisted of two chests of porcelain, a saber, a powder horn, two elegant golden watches, a ring, two Dutch rugs, and a selection of coffee and tea. This gesture was intended to serve as both a present and a reminder of the positive diplomatic relations between the two nations.

However, Dabenis immediately set sail to avoid any further formalities, and invitations that could potentially incur additional expenses for the Dutch Republic.[18] Rossignol, the envoy tasked with delivering a gift to the Moroccan king, decided to wait even longer, hoping for instructions from the States General.

The governor of Larache spotted him and informed the king about the pending gift. The king, who was residing in Meknes, then sent a formal escort consisting of three officers and twenty horses to bring Rossignol and the gift to him. On October 3, Rossignol was escorted from Larache and arrived in Meknes on September 7. However, he received word that the king had left a few days earlier to visit a military camp in the mountains near Fez. On October 14, Rossignol finally reached Fez, where he was allowed to stay in the house of Prince Muley Absalem.

On October 17, Rossignol was finally granted an audience with the king. However, two of the king's servants delivered the gifts to the king on his behalf, as Rossignol was not allowed to personally meet the king, a restriction that had been in place for two years. He was instructed to wait in the king's garden until he received his gifts back, since the king, displeased with the presents, informed Rossignol that he could take them back to the Dutch Republic. Rossignol, however, argued that this would be considered an insult to the States General and could potentially provoke a war.[19]

On the following day, which was October 19th, Rossignol departed from Fez, taking with him the gifts and a letter from the Moroccan king addressed to the States General. Though the letter was written in Arabic, The States General received it, and did not declare war. Instead, the States General responded by sending a letter expressing their unwillingness to provide additional gifts, while expressing their hope for continued peaceful relations.

On October 23, Rossignol arrived back in Larache, where he dispatched a letter to the States General containing reports about his mission. In the letter, he mentioned that the king had expressed a desire for more and better gifts. He also described the opulence of Morocco, noting the wealth of everyone in Prince Muley Absalem's household and the non-negotiable nature of the Moroccans. While sending his report from Cadiz to The Hague, Rossignol received a surprising letter on November 1. To his astonishment, he found two letters, both authored by Samuel Sumbel, the right-hand man of the Sultan.

The first letter formally declared war on the Dutch Republic[20] signed by the king himself to lend authority, the second letter delved into the reasons behind the king's shift from his initial decision of abstaining from declaring war to ultimately opting for war against the Dutch Republic. The primary cause for this declaration of war stemmed from an incident wherein Dutch ships, mistakenly, attacked a Moroccan vessel, mistaking it for an Algerian one. Rossignol, the envoy, was suprised that Morocco declared war since, they just started a war with Spain, and tensions were rising with Algeria, nevertheless he dispatched both letters to the States General. Upon receiving the letter, the States General accepted the declaration of war on January 1, 1775, and decided to knock out the Moroccans for good.[21]

War

The States General wasted no time in taking action. Captain Dabenis, who was stationed in the Strait of Gibraltar with eight Warships, received orders to impose a blockade on Moroccan ports, preventing any Moroccan pirates from seizing Dutch ships. This worked excellent, no Moroccan pirate touched any Dutch ship due to this blockade, only 1 small engagement took place near the coast of Tanger, in which a Dutch ship, chased a Moroccan ship until it stranded, and was severely damaged. After approximately six months, Dabenis safely escorted around 100 Dutch Merchant Vessels across the Strait of Gibraltar. As a result of a lack of Moroccan pirate activity, his fleet was reduced to eight frigates and one ship of the line. In 1775, Captain Dabenis was replaced by Flag Officer Hartsinck, who in turn, was succeeded by Daniel Pichot in 1776, with a brief interim appointment of Lodewijk van Bylandt during that time. The blockade of Moroccan ports, and coast was initiated by Bylandt, Picker, and Kinsbergen, who commanded a force consisting of eight to twelve Warships. Remarkably, Dutch diplomat Rassignol in Morocco remained in their posts, and Dutch traders were not subjected to capture; instead, they were allowed to operate freely in Morocco. They even received official passports from the Moroccan king to facilitate their trading activities, which significantly contributed to Morocco's economy. The States General refrained from intervening with the traders too, due to an old Dutch law permitting trade with the enemy as long as it generated profits. Numerous encounters occurred along the Moroccan coast, including an incident on June 10, 1776, when a Dutch frigate mistakenly attacked what was believed to be a Moroccan vessel on the coast of Larache but turned out to be an Algerian ship.[10][22][23] The king didn't want to give up the war until the Dutch gave him more gifts, and tribute then Algiers, the Dutch did not accept as they regarded it as a humiliation, and the Dutch decided to wage even harder war against the Moroccans[22] The king of Morocco said in an audition that he will surely win the war, and the Hollanders would beg him for peace, even tho all he saw all of his ships just laying in the bay doing nothing due to the Dutch blockade, so he decided in June 1776 sent out two frigates, 4 Xebecs, and 2 Rowboats to set out and capture specifically Dutch ships the two frigates managed to slip through the blockade and capture two merchant vessels. The seized goods were taken to Mogador, where 35 Dutch sailors were detained. Remarkably, they were not sold into slavery but were personally addressed by the king himself. He conveyed that they were not to be considered slaves and hadn't attacked his ships. Instead, he requested them to convey a message to the States General. He asked them to deliver the king's request for a gift in 1776. Later that same year, these two Moroccan frigates set sail to Cape St. Vincent, where they attacked two Dutch fluyts, and took their goods. However, before returning to Morocco, they encountered two Dutch frigates under the command of Bentinck and Dedel. In the ensuing battle, the Dutch emerged victorious, pursuing the Moroccan ships until they stranded. Taibi and Ali, leaders of the Moroccan frigates, fled, albeit separately. Taibi's damaged frigate endured Dutch fire until it was eventually destroyed. Ali faced the same fate, at the entrance of Marmora with the king's 3 best Xebecs. This defeat marked a significant loss for the Moroccan king.[13][6][24][11] The loss of his two best ships, another Frigate, along with the sinking of 50 irreplaceable cannons, was a significant blow, and his fleet practically unuseable, and his seamight destroyed. These incidents, and the frustrating blockade, ultimately forced the king to ask for peace. He sent a letter to the States general asking for peace, events progressed swiftly from there. Van Kinsbergen was dispatched with two frigates, posing as an "ambassador." He was warmly received and eventually negotiated a peace agreement with the king. As part of the accord, 58–75 Dutch slaves were liberated without the need for any ransom payment, and the Dutch no longer needed to give presents. [25][26][27][8][28][17] The following day, near Arzilla, two Dutch frigates pursued four Moroccan Galiots, causing significant damage to one of them. This occurred despite the Moroccans signaling a white flag. However, the Dutch frigates were unaware of the treaty at the time. Later, on July 4, the States General issued an apology for the incident. In response, the Moroccan king ratified the peace agreement with Admiral Picot, expressing his desire for friendship and the restoration of peaceful relations between the two nations.[7]

Aftermath

In the Dutch Republic, both the populace and the States General were happy with the peace, especially the traders. This conflict is often considered the most significant war between the Dutch and the Moroccans,[7] yet it remains largely overlooked and rarely discussed. After the war, diplomatic relations between the involved parties remained great. Dutch traders actively engaged in commerce along the Moroccan coastline, benefiting from a generous grant of liberty to trade with all ships, access Moroccan ports, the Dutch also did not send Morocco any more gifts after this won war, and the Dutch slaves in Moroccan captivity[6] were sent home free. Furthermore, the Moroccan emperor forged peaceful agreements with several other nations, including Denmark-Norway, Sweden, and the United States.[29][17][27]

References

- Vrolijk & van Leeuwen 2013, p. 81.

- Mollema 1939, p. 254.

- Waterreus 1865, p. 138.

- Jonge & Jakob Jonge 1861, p. 23.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 369.

- De Europische reiziger, of De geest der nieuwstydingen. Bevattende, behalven het voornaamste staatsnieuws, verscheide aangenaame byzonderheden, en gewichtige scheepsberichten Volume 1 (in Dutch). Gedrukt voor den auteur, en te bekomen in den boekwinkel van C. van Cassenberg en W. van den Brink #op den Dam#. 1777. p. 69.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 46.

- van der Pyl & Bensdorp 1816, p. 178.

- Jonge & Jakob Jonge 1861, p. 367.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 43.

- Jonge & Jakob Jonge 1861, p. 369.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 44-45.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 44.

- Dewald 1856, p. 190.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 39-46.

- Bruijn 2017, p. 136.

- van der Bijl 2013, p. 62.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 39.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 40.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 41.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 42.

- Jonge & Jakob Jonge 1861, p. 368.

- Bruijn 2017, p. 181.

- Zuidhoek 2022, p. 762.

- Veenendaal 1975, p. 45.

- De Leidsman der jeugd Volume 11 (in Dutch). 1839. p. 308.

- van der Pyl & Bensdorp 1816, p. 179.

- Blok & Molhuysen 1918, p. 384.

- Wilkes 1819, p. 11.

- The war declaration letter was sent out on 30 October 1774, and received by the States General on 3 November 1774, however the declaration was officially accepted on 1 January 1775, so some sources will tell you it started in 1774, but most will tell you in 1775

Sources

- Veenendaal, A.J (1975). Matthijs Sloot : een zeeman uit de achttiende eeuw, 1719–1779 (in Dutch). Nijhoff. ISBN 9024717981.

- Waterreus, J. (1865). Geschiedenis der Noordelijke Nederlanden (in Dutch). Arkesteyn.

- Dewald, H.P. (1856). Chronologisch handboek bij de beoefening der Ned. geschiedenis Volume 1 (in Dutch).

- Vrolijk, Arnoud; van Leeuwen, Richard (2013). Arabic Studies in the Netherlands A Short History in Portraits, 1580–1950 (E-book ed.). Brill. ISBN 9789004266339.

- Jonge, Johannes Cornelis; Jakob Jonge, Jan Karel (1861). Geschiedenis van het Nederlandsche zeewezen Dl. 4 (in Dutch). KB, Nationale Bibliotheek van Nederland: Kruseman.

- Bruijn, Jaap R (2017). The Dutch Navy of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (E book ed.). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781786948908.

- Blok, P.J.; Molhuysen, P.C. (1918). Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek. Deel 4 (in Dutch).

- Wilkes, John (1819). Encyclopaedia Londinensis Volume 16.

- Zuidhoek, Arne (2022). The Pirate Encyclopedia The Pirate's Way (E-book ed.). Brill. ISBN 9789004515673.

- Mollema, J.C. (1939). Geschiedenis van Nederland ter zee (in Dutch). Uitgeversmaatschappij Joost van den Vondel.

- van der Pyl, R.; Bensdorp, J. C. (1816). Korte beschrijving der staten van Barbarije, Marokko, Algiers, Tunis en Fezzan benevens een naauwkeurig verhaal van de roemrijke overwinning, door de gecombineerde Britsche en Nederlandische vloten ... onlangs voor Algiers behaald (in Dutch). KB, Nationale Bibliotheek van Nederland (original from Universiteitsbibliotheek Vrije Universiteit): Blussé.

- van der Bijl, Yvonne (2013). Marokko (in Dutch) (E-book ed.). Elmar B.V., Uitgeverij. ISBN 9789038920801.