Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar (Arabic: مضيق جبل طارق, romanized: Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; Spanish: Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules) is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

| Strait of Gibraltar | |

|---|---|

The Strait of Gibraltar as seen from space. The Iberian Peninsula is on the left and North Africa is on the right. | |

Strait of Gibraltar Location of the Strait of Gibraltar between Africa (centre right) and Europe (top right), connecting the Atlantic Ocean in the centre to the Mediterranean Sea on the right | |

| Location | Atlantic Ocean – Mediterranean Sea |

| Coordinates | 35°58′N 5°29′W |

| Type | Strait |

| Native name | |

| Basin countries | |

| Min. width | 13 km (8.1 mi) |

| Max. depth | 900 metres (2,953 ft) |

The two continents are separated by 13 kilometres (8.1 miles; 7.0 nautical miles) of ocean at the Strait's narrowest point between Point Marroquí in Spain and Point Cires in Morocco.[1] Ferries cross between the two continents every day in as little as 35 minutes. The Strait's depth ranges between 300 and 900 metres (980 and 2,950 feet; 160 and 490 fathoms).[2]

The strait lies in the territorial waters of Morocco, Spain, and the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, foreign vessels and aircraft have the freedom of navigation and overflight to cross the strait of Gibraltar in case of continuous transit.

Names and etymology

The name comes from the Rock of Gibraltar, which in turn originates from the Arabic Jabal Ṭāriq (meaning "Tariq's Mount"),[3] named after Tariq ibn Ziyad. It is also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, the Gut of Gibraltar (although this is mostly archaic),[4] the STROG (STRait Of Gibraltar) in naval use.[5]

Another Arabic name is Bāb al-maghrib (Arabic: باب المغرب), meaning "Gate of the West" or "Gate of the sunset", and furthermore "Gate of the Maghreb" or "Gate of Morocco". In the Middle Ages it was called in Arabic Az-Zuqāq (الزقاق), "the Passage" and by the Romans Fretum Gaditanum (Strait of Cadiz).[6]

In Latin it has been called Fretum Herculeum,[7] based on the name from antiquity "Pillars of Hercules" (Ancient Greek: αἱ Ἡράκλειοι στῆλαι, romanized: hai Hērákleioi stêlai),[8] referring to the mountains as pillars, such as Gibraltar, flanking the strait.

Location

On the northern side of the Strait are Spain and Gibraltar (a British overseas territory in the Iberian Peninsula), while on the southern side are Morocco and Ceuta (a Spanish autonomous city in northern Africa). Its boundaries were known in antiquity as the Pillars of Hercules.

Due to its location, the Strait is commonly used for illegal immigration from Africa to Europe.[9]

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Strait of Gibraltar as follows:[10]

- On the West. A line joining Cape Trafalgar to Cape Spartel.

- On the East. A line joining Europa Point to the Peninsula of Almina.

Geology

The seabed of the Strait is composed of synorogenic Betic-Rif clayey flysch covered by Pliocene and/or Quaternary calcareous sediments, sourced from thriving cold water coral communities.[11] Exposed bedrock surfaces, coarse sediments and local sand dunes attest to the strong bottom current conditions at the present time.

Around 5.9 million years ago, the connection between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean along the Betic and Rifan Corridor was progressively restricted until its total closure, effectively causing the salinity of the Mediterranean to rise periodically within the gypsum and salt deposition range, during what is known as the Messinian salinity crisis. In this water chemistry environment, dissolved mineral concentrations, temperature and stilled water currents combined and occurred regularly to precipitate many mineral salts in layers on the seabed. The resultant accumulation of various huge salt and mineral deposits about the Mediterranean basin are directly linked to this era. It is believed that this process took a short time, by geological standards, lasting between 500,000 and 600,000 years.

It is estimated that, were the Strait closed even at today's higher sea level, most water in the Mediterranean basin would evaporate within only a thousand years, as it is believed to have done then, and such an event would lay down mineral deposits like the salt deposits now found under the sea floor all over the Mediterranean.

After a lengthy period of restricted intermittent or no water exchange between the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean basin, approximately 5.33 million years ago,[12] the Atlantic–Mediterranean connection was completely reestablished through the Strait of Gibraltar by the Zanclean flood, and has remained open ever since.[13] The erosion produced by the incoming waters seems to be the main cause for the present depth of the Strait (900 m (3,000 ft; 490 fathoms) at the narrows, 280 m (920 ft; 150 fathoms) at the Camarinal Sill). The Strait is expected to close again as the African Plate moves northward relative to the Eurasian Plate,[14] but on geological rather than human timescales.

Biodiversity

The Strait has been identified as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of the hundreds of thousands of seabirds which use it every year to migrate between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, including significant numbers of Scopoli's and Balearic shearwaters, Audouin's and lesser black-backed gulls, razorbills, and Atlantic puffins.[15]

A resident orca pod of some 36 individuals lives around the Strait, one of the few that are left in Western European waters. The pod may be facing extinction in the coming decades due to long term effects of PCB pollution.[16]

History

Evidence of the first human habitation of the area by Neanderthals dates back to 125,000 years ago. It is believed that the Rock of Gibraltar may have been one of the last outposts of Neanderthal habitation in the world, with evidence of their presence there dating to as recently as 24,000 years ago.[17] Archaeological evidence of Homo sapiens habitation of the area dates back c. 40,000 years.

The relatively short distance between the two shores has served as a quick crossing point for various groups and civilizations throughout history, including Carthaginians campaigning against Rome, Romans travelling between the provinces of Hispania and Mauritania, Vandals raiding south from Germania through Western Rome and into North Africa in the 5th century, Moors and Berbers in the 8th–11th centuries, and Spain and Portugal in the 16th century.

Beginning in 1492, the Strait began to play a certain cultural role in acting as a barrier against cross-channel conquest and the flow of culture and language that would naturally follow such a conquest. In that year, the last Muslim government north of the Strait was overthrown by a Spanish force. Since that time, the Strait has come to foster the development of two very distinct and varied cultures on either side of it after sharing much the same culture for over 500 years from the 8th century to the early 13th century.

On the northern side, Christian-European culture has remained dominant since the expulsion of the last Muslim kingdom in 1492, along with the Romance Spanish language, while on the southern side, Muslim-Arabic/Mediterranean has been dominant since the spread of Islam into North Africa in the 700s, along with the Arabic language.

The small British enclave of the city of Gibraltar presents a third cultural group found in the Strait. This enclave was first established in 1704 and has since been used by the United Kingdom to act as a surety for control of the sea lanes into and out of the Mediterranean.

Following the Spanish coup of July 1936 the Spanish Republican Navy tried to blockade the Strait of Gibraltar to hamper the transport of Army of Africa troops from Spanish Morocco to Peninsular Spain. On 5 August 1936 the so-called Convoy de la victoria was able to bring at least 2,500 men across the Strait, breaking the republican blockade.[18]

Communications

The Strait is an important shipping route from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. There are ferries that operate between Spain and Morocco across the Strait, as well as between Spain and Ceuta and Gibraltar to Tangier.

Tunnel across the Strait

Discussion between Spain and Morocco of a tunnel under the strait began in the 1980s. In December 2003, both countries agreed to explore the construction of an undersea rail tunnel to connect their rail systems across the Strait. The gauge of the rail would be 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) to match the proposed construction and conversion of significant parts of the existing broad gauge system to standard gauge.[19] While the project remained in a planning phase, Spanish and Moroccan officials met to discuss it occasionally, including in 2012.[20] Those talks led to nothing constructive happening, but in April 2021 ministers from both countries agreed to a joint intergovernmental meeting to be held in Casablanca in the coming months. This was in order to resume discussions on a tunnel.[21][22] Earlier, in January 2021, the UK government had studied plans for a tunnel to link Gibraltar with Tangiers that would replace the Spanish-Moroccan project that until then had had no tangible results after over 40 years of discussions.[23]

Special flow and wave patterns

The Strait of Gibraltar links the Atlantic Ocean directly to the Mediterranean Sea. This direct linkage creates certain unique flow and wave patterns. These unique patterns are created due to the interaction of various regional and global evaporative forces, water temperatures, tidal forces, and wind forces.

Inflow and outflow

Water flows through the Strait more or less continuously, both eastwards and westwards. A smaller amount of deeper, saltier and therefore denser waters continually flow westwards (the Mediterranean outflow), while a larger amount of surface waters with lower salinity and density continually flow eastwards (the Mediterranean inflow). These general flow tendencies may be occasionally interrupted for brief periods by temporary tidal flows, depending on various lunar and solar alignments. The balance of the water flow is eastwards, since the evaporation rate within the Mediterranean basin is higher than the combined inflow of all the rivers that empty into it, plus the total precipitation of rain or snow that falls on it.[24] At the Strait's far western end is the Camarinal Sill, the Strait's shallowest point which limits mixing between the cold, less saline Atlantic water and the warmer, more saline Mediterranean waters.

The Mediterranean waters are so much saltier than the Atlantic waters that they sink below the constantly incoming water and form a highly saline (thermohaline, both warm and salty) layer of bottom water. This layer of bottom-water constantly works its way out into the Atlantic as the Mediterranean outflow. On the Atlantic side of the Strait, a density boundary separates the Mediterranean outflow waters from the rest at about 100 m (330 ft; 55 fathoms) depth. These waters flow out and down the continental slope, losing salinity, until they begin to mix and equilibrate more rapidly, much farther out at a depth of about 1,000 m (3,300 ft; 550 fathoms). The Mediterranean outflow water layer can be traced for thousands of kilometres west of the Strait, before completely losing its identity.

.jpg.webp)

During the Second World War, German U-boats used the currents to pass into the Mediterranean Sea without detection, by maintaining silence with engines off.[25] From September 1941 to May 1944 Germany managed to send 62 U-boats into the Mediterranean. All these boats had to navigate the British-controlled Strait of Gibraltar where nine U-boats were sunk while attempting passage and 10 more had to break off their run due to damage. No U-boats ever made it back into the Atlantic and all were either sunk in battle or scuttled by their own crews.[26]

Internal waves

Internal waves (waves at the density boundary layer) are often produced by the Strait. Like traffic merging on a highway, the water flow is constricted in both directions because it must pass over the Camarinal Sill. When large tidal flows enter the Strait and the high tide relaxes, internal waves are generated at the Camarinal Sill and proceed eastwards. Even though the waves may occur down to great depths, occasionally the waves are almost imperceptible at the surface, at other times they can be seen clearly in satellite imagery. These internal waves continue to flow eastward and to refract around coastal features. They can sometimes be traced for as much as 100 km (62 mi; 54 nmi), and sometimes create interference patterns with refracted waves.[27]

Territorial waters

Except for its far eastern end, the Strait lies within the territorial waters of Spain and Morocco. The United Kingdom claims 3 nautical miles (5.6 km; 3.5 mi) around Gibraltar on the northern side of the Strait, putting part of it inside British territorial waters. As this is less than the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) maximum, it means, according to the British claim, that part of the Strait lies in international waters. The ownership of Gibraltar and its territorial waters is disputed by Spain. Similarly, Morocco disputes Spanish sovereignty over Ceuta on the southern coast.[28] There are several islets, such as the disputed Isla Perejil, that are claimed by both Morocco and Spain.[29]

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, vessels passing through the strait do so under the regime of transit passage, rather than the more limited innocent passage allowed in most territorial waters. Therefore, a vessel or aircraft has the freedom of navigation or overflight for the purpose of crossing the strait of Gibraltar.[28][30]

Power generation

Some studies have proposed the possibility of erecting tidal power generating stations within the Strait, to be powered from the predictable current at the Strait.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Atlantropa project proposed damming the Strait to generate large amounts of electricity and lower the sea level of the Mediterranean by several hundreds of meters to create large new lands for settlement.[31] This proposal would however have devastating effects on the local climate and ecology and would dramatically change the strength of the West African Monsoon.

See also

References

- "Strait of Gibraltar | channel". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- See Robinson, Allan Richard and Paola Malanotte-Rizzoli, Ocean Processes in Climate Dynamics: Global and Mediterranean Examples. Springer, 1994, p. 307, ISBN 0-7923-2624-5.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 938.

- "Google Books Ngram Viewer results "Strait of Gibraltar/Gut of Gibraltar"".

- See, for instance, Nato Medals: Medal for Active Endeavor Archived 2006-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, awarded for activity in the international water of the Mediterranean and STROG.

- Pamphlet of the Museum of the Castle of Guzman el Bueno, [El Ayuntamiento de Tarifa] accessed 16 November 2016.

- "Strait of Gibraltar - channel". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- Strabo Geographia 3.5.5.

- "Migration Information Source – The Merits and Limitations of Spain's High-Tech Border Control". Migrationinformation.org. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- De Mol, B., et al. 2012. "Ch. 45: Cold-Water Coral Distribution in an Erosional Environment: The Strait of Gibraltar Gateway", in: Harris, P. T.; Baker, E. K. (eds.), Seafloor geomorphology as benthic habitat: GEOHAB Atlas of seafloor geomorphic features and benthic habitats. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 636–643.

- At the Miocene/Pliocene boundary, c. 5.33 million years before the present

- Cloud, P., Oasis in space. Earth history from the beginning, New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., p. 440. ISBN 0-393-01952-7

- Johnson, Scott K. (2013-07-25). "Gibraltar might be the beginning of the end for the Atlantic Ocean". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2021-03-18.

- "Data Zone: Strait of Gibraltar". BirdLife. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- Carrington, Damian (2018-09-27). "Orca 'apocalypse': half of killer whales doomed to die from pollution". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- "Last of the Neanderthals". National Geographic. October 2008. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- Beevor, Antony (2006) [1982]. The Battle for Spain. Orion. ISBN 978-0-7538-2165-7.

- "Europe-Africa rail tunnel agreed". BBC News.

- "Tunnel to Connect Morocco with Europe". bluedoorhotel.com. February 17, 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-11-04.

- "Strait of Gibraltar underwater railway tunnel project coming back to life". Construction Review Online. 15 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- "Morocco, Spain discuss revival of fixed link project via Gibraltar Strait". The North Africa Post. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Alaoui, Mohamed (9 January 2021). "British-Moroccan undersea tunnel would connect Africa to Europe". The Arab Weekly. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Soto-Navarro, Javier; Criado-Aldeanueva, Francisco; García-Lafuente, Jesús; Sánchez-Román, Antonio (2010-10-12). "Estimation of the Atlantic inflow through the Strait of Gibraltar from climatological and in situ data". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (C10): C10023. Bibcode:2010JGRC..11510023S. doi:10.1029/2010JC006302. ISSN 0148-0227.

- Paterson, Lawrence (2007). U-Boats in the Mediterranean 1941–1944. Chatham Publishing, pp. 19 and 182. ISBN 9781861762900

- "U-boat war in the Mediterranean". uboat.net. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- Wesson, J. C.; Gregg, M. C. (1994). "Mixing at Camarinal Sill in the Strait of Gibraltar". Journal of Geophysical Research. 99 (C5): 9847–9878. Bibcode:1994JGR....99.9847W. doi:10.1029/94JC00256.

- Víctor Luis Gutiérrez Castillo (April 2011). The Delimitation of the Spanish Marine Waters in the Strait of Gibraltar (PDF) (Report). Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Tremlett, Giles (13 July 2002). "Moroccans seize Parsley Island and leave a bitter taste in Spanish mouths". The Guardian.

- Rothwell, Donald R. (2009). "Gibraltar, Strait of". Oxford Public International Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/e1172. ISBN 9780199231690. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Atlantropa: A plan to dam the Mediterranean Sea". Xefer blog. 16 March 2005. Retrieved on 13 August 2012.

External links

- Climate Control Requires a Dam at the Strait of Gibraltar Archived 2009-02-22 at the Wayback Machine—American Geophysical Union, 1997. Accessed 26 February 2006. Gone 12 February 2010. Dam design at http://www.agu.org/sci_soc/eosrjohnsonf3.gif Archived 2012-09-26 at the Wayback Machine Building the dam and letting the Mediterranean Sea completely evaporate would raise Sea Level 15 meters over 1,000 years. Evaporating the first 100 meters or so would raise Sea Level 1 meter in about 100 years.

- Project for a Europe-Africa permanent link through the Strait of Gibraltar—United Nations Economic and Social Council, 2001. Accessed 26 February 2006.

- Estudios Geográficos del Estrecho de Gibraltar—La Universidad de Tetuán and La Universidad de Sevilla. Accessed 26 February 2006. (in Spanish)

- "Solitons, Strait of Gibraltar". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 2004-08-17. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- "Internal Waves, Strait of Gibraltar". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 2001-06-20. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

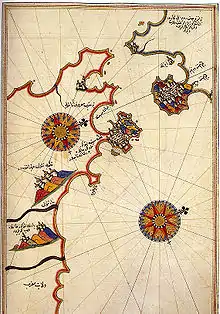

- Old maps of the Strait of Gibraltar, Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel

- HOW TO SWIM ACROSS THE STRAIT OF GIBRALTAR By ACNEG The Straits of Gibraltar Swimming Association.

.svg.png.webp)