Duxford Aerodrome

Duxford Aerodrome (ICAO: EGSU) is located 8 nautical miles (15 km; 9.2 mi) south of Cambridge, within the civil parish of Duxford, Cambridgeshire, England and nearly 1-mile (1.6 km) west of the village. The airfield is owned by the Imperial War Museum (IWM) and is the site of the Imperial War Museum Duxford and the American Air Museum.

Duxford Aerodrome RAF Duxford USAAF Station 357 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

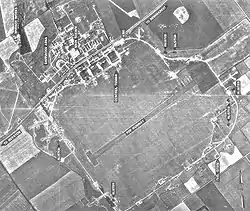

Duxford - 9 July 1946 | |||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Private-owned, Public-use | ||||||||||||||

| Owner | Imperial War Museum & Cambridgeshire County Council | ||||||||||||||

| Operator | Imperial War Museum | ||||||||||||||

| Serves | Imperial War Museum Duxford | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Duxford | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 125 ft / 38 m | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 52°05′27″N 000°07′55″E | ||||||||||||||

| Website | Information for Pilots | ||||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||||

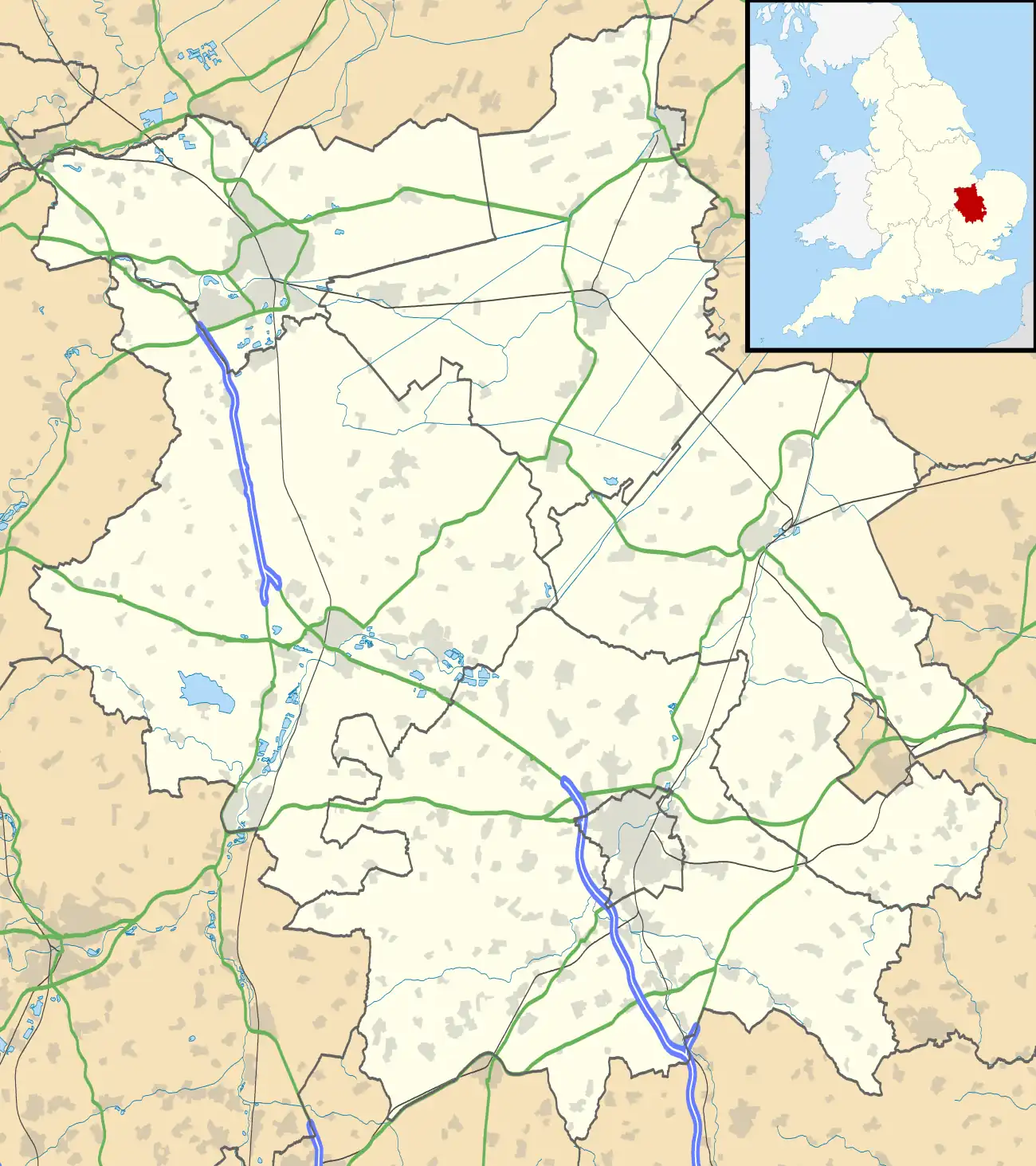

EGSU Location in Cambridgeshire | |||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Duxford Aerodrome has a Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) Ordinary Licence (Number P678) that allows flights for the public transport of passengers or for flying instruction as authorised by the licensee (Cambridgeshire County Council). The aerodrome is not licensed for night use.[2]

History

Early Use

The area around Duxford was first used for military purposes as part of the Army Manoeuvres of 1912.[3] It was not until October 1917 that construction was started on a more formal airfield. The new aerodrome was built as part of a pair with a sister station at Fowlmere.[3]

The hangars built in the period correspond to a Directorate of Fortifications and Works drawing number 332/17. The drawing was signed by Lieutenant-Colonel BHO Armstrong of the Royal Engineers.[4]

The first units arriving at the new Training Depot Station in March 1918. These new arrivals included members of the American Expeditionary Forces.[3]

Duxford airfield dates to 1918 when many of the buildings were constructed by German prisoner-of-war labour. The airfield housed 8 Squadron in 1919–1920 which was equipped with Bristol Fighters. The airfield was then used by No. 2 Flying Training School RAF until April 1923, when 19 Squadron was formed at Duxford with Sopwith Snipes.

Inter War Years

Following the First World War the airfield was retained by the Royal Air Force as a training school. It was then reclassified as a fighter station from 1 April 1923.[3]

By 1925 Duxford's three fighter squadrons had expanded to include the Gloster Grebes and Armstrong Whitworth Siskins. No.19 Squadron was re-equipped with Bristol Bulldogs in 1931, and in 1935, was the first squadron to fly the RAF's fastest new fighter, the Gloster Gauntlet, capable of 230 mph (375 km/h).

The wooden-framed barrack buildings (with one exception) were replaced, beginning in 1928.[3]

A further round of works took place in 1931, with the base headquarters, guardroom and domestic buildings being constructed. The first of the domestic buildings ready for use was the Sergeant's Mess.[3]

Further rounds of building took place in 1935 (Scheme 'A') and in 1939 (Scheme 'M').[3]

On 6 July 1935, Duxford hosted a Silver Jubilee Review before King George V who observed 20 squadrons from a dais on the aerodrome.[5]

In 1936 Flight Lieutenant Frank Whittle, who was studying at Cambridge University, flew regularly from Duxford as a member of the Cambridge University Air Squadron. Whittle went on to develop the jet turbine as a means of powering an aircraft.[6]

In 1938 No. 19 Squadron was the first RAF squadron to receive the new Supermarine Spitfire. The third production Spitfire (K9789) was presented to the squadron at Duxford on 4 August 1938 by Jeffrey Quill, Supermarine's chief test pilot.[7][8]

Second World War

The air defence of the United Kingdom by RAF Fighter Command was divided into areas, known as groups. RAF Duxford was the southern most station in the area covered by 12 Group under the command of Air Vice-Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory. The group was responsible for the defence of the Midlands, East Anglia and some of northern England.[3][9]

By June 1940 Belgium, the Netherlands and France were under German control and the invasion of Britain was their next objective (Operation Sea Lion). Duxford was placed in a high state of readiness, and to create space for additional units at Duxford, 19 Squadron moved to nearby RAF Fowlmere.

The dominance of the skies over Britain would be crucial to keeping German forces out of the country, this became known as The Battle of Britain. Hurricanes first arrived at Duxford in July with the formation of 310 Squadron, which consisted of Czechoslovakian pilots who had escaped from France.

On 9 September the Duxford squadrons successfully intercepted and turned back a large force of German bombers before they reached their target. This proved Duxford's importance, (but see the article on the Big Wing), so two more squadrons were added, No. 302 (Polish) Squadron RAF with Hurricanes, and the Spitfires of No. 611 Auxiliary Squadron which had mobilised at Duxford a year before.

On average sixty Spitfires and Hurricanes were dispersed around Duxford and RAF Fowlmere every day. On 15 September 1940 they twice took to the air to repulse Luftwaffe aircraft intent on bombing London. RAF Fighter Command was victorious, the threat of invasion passed and Duxford's squadrons had played a critical role. This became known as 'Battle of Britain Day'.

In recognition of the efforts, achievements and sacrifices made by the squadrons and airmen during the Battle of Britain, the "gate guard" aircraft on display at the entrance gate to IWM Duxford is a Hawker Hurricane II, squadron code WX-E of No.302 (Polish) Squadron, Serial No. P2954, flown by Flight Lieutenant Tadeusz Paweł Chłopik, RAF (Polish Air Force).

The 'Big Wing'

Douglas Bader, who commanded 242 Squadron (originally at RAF Coltishall), came up with a strategy known as the 'Big Wing'. This involved the deployment of 3 (later 5) squadrons of Spitfires and Hurricanes to engage the enemy.[3]

There was disagreement between commanders as to the merits of the strategy. This culminated in the removal of Sir Hugh Dowding as Commander in Chief at Fighter Command, as well as the replacement of Air Vice-Marshall Keith Park at 11 Group by Leigh-Mallory.[3]

Air Fighting Development Unit

Duxford became the home of several specialist units, including the Air Fighting Development Unit (AFDU), which moved to the station in December 1940.[3]

The work of the AFDU including the testing and evaluation of the Hawker Typhoon, the Mosquito and the Mustang.[3]

In 1942 the first Typhoon Wing was formed. Its first operation took place on 20 June 1942.

The AFDU's equipment included captured German aircraft, which were restored to flying condition for evaluation.

Other RAF Fighter Command units which operated from Duxford were : 19, 56, 66, 133, 181, 195, 222, 242, 264, 266, 310, 312, 601, 609, 611 Squadrons and the AFDU.

United States Army Air Forces

Duxford airfield was assigned to the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) on 1 April 1943[3] and then became known by the USAAF as "Station 357 (DX)". It was allocated to the Eighth Air Force's VIII Fighter Command.

USAAF Station Units assigned to RAF Duxford were:[10]

- 79th Service Group[11]

- 84th and 378th Service Squadrons; HHS, 79th Service Group

- 18th Weather Squadron

- 23rd Station Complement Squadron

- 1042nd Signal Company

- 1099th Quartermaster Company

- 1671st Ordnance Supply & Maintenance Company

- 989th Military Police Company

- 2027th Engineer Fire Fighting Platoon

Duxford was the initial home of the 5th Air Defense Wing which arrived from Norfolk Municipal Airport, Virginia on 3 July 1943. The unit was re designated the 66th Fighter Wing and was transferred to Sawston Hall near Cambridge on 20 August 1943.

Combat flying units assigned were:

- 350th Fighter Group

The 350th Fighter Group was activated at Duxford on 1 October 1942 by special authority granted to the Eighth Air Force with a nucleus of Bell P-39 Airacobra pilots with the intention of providing a ground attack fighter organisation for the Twelfth Air Force in the forthcoming Operation Torch, (the invasion of North Africa). Initially, the group received export versions of the Airacobra, known as the P-400, and a few Spitfires.

The air echelon moved to Oujda, French Morocco during January–February 1943. After this the last RAF units moved out and on 15 June 1943 Duxford was officially handed over to the Eighth Air Force.

- 78th Fighter Group

The 78th Fighter Group arrived at Duxford from RAF Goxhill in April 1943. Upon transfer from Goxhill, the group lost its Lockheed P-38 Lightnings when these aircraft were withdrawn for use as replacements for units fighting in North Africa. In addition most of the 78th FG's pilots were also transferred to the Twelfth Air Force as replacements. Thus the group was re-equipped with Republic P-47C Thunderbolts and remained at Duxford. Aircraft of the group were identified by a black/white chequerboard pattern.

The group consisted of the following squadrons:

- 82d Fighter Squadron (MX)

- 83d Fighter Squadron (HL)

- 84th Fighter Squadron (WZ)

The 78th FG was first equipped with P-47s and converted to P-51 Mustangs in December 1944. The group flew many missions to escort Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers that attacked industrial complexes, submarine yards and docks, V-weapon sites and other targets in Continental Europe. The unit also engaged in counter-air activities and on numerous occasions strafed and dive-bombed airfields, trains, vehicles, barges, tugs, canal locks, barracks and troops.

In addition to other operations, the 78th participated in the intensive campaign against Luftwaffe aircraft industry during Big Week, 20–25 February 1944 and helped to prepare the way for the invasion of France. The group supported the Normandy landings in June 1944 and contributed to the breakthrough at Saint-Lô in July. The unit participated in the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944-January 1945 and supported Operation Varsity, the airborne assault across the Rhine, in March.

The 78th Fighter Group received a Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC) for activities connected with Operation Market Garden, the airborne attack on the Netherlands, in September 1944 when the group covered troop carrier and bombardment operations and carried out strafing and dive-bombing missions. The group received a second DUC for destroying numerous aircraft on five airfields near Prague and Pilsen in Czechoslovakia on 16 April 1945.

The 78th Fighter Group returned to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey in October 1945 and was inactivated on 18 October.

Postwar use

On 1 December 1945, a few weeks after the departure of the 78th Fighter Group, Duxford was returned to the RAF. For the next sixteen years, it remained an RAF Fighter Command station, although it was closed for two years from October 1949 to have a single concrete runway laid. This, together with a new perimeter track and apron, enabled better handling of jet aircraft with which Fighter Command was re-equipping.

Duxford reopened in August 1951. In 1957, 64 Squadron operated Gloster Javelins and 65 Squadron flew Hawker Hunters. These were the last two operational squadrons to fly from the airfield. Two years later, Duxford was chosen to provide the aircraft for the 1953 Coronation Flypast.

Duxford was too far south and too far inland to be strategically important and the costly improvements required for modern supersonic fighters could not be justified. In July 1961 the last operational RAF flight was made from Duxford by a Gloster Javelin FAW.7.

On 1 August 1961, a Gloster Meteor NF.14 made the last take off from the runway before Duxford closed as an RAF airfield and was abandoned.

Filming and other civilian uses

In 1968 Duxford was used as one of the locations for the shooting of the film Battle of Britain.[3] On 21 June and 22 June, one of the original World War I hangars was blown up in stages for the filming (without the concurrence of the Ministry of Defence) and the airfield was spectacularly filmed from the air in a realistic bombing sequence. Ironically this was the nearest Duxford came to being destroyed as no significant wartime German raids were carried out on the aerodrome. The French château, seen at the beginning of the film, was constructed on the south-west corner of the airfield.

Around 1968 the Cambridge University Gliding Club moved some of its flying to Duxford. Subsequently, all club flying was moved to the site.

In 1969 The Ministry of Defence declared its intention to dispose of Duxford. Plans were even made for a sports centre or a prison but were never finalised.

In 1976 Sir Douglas Bader spoke before a public inquiry against proposals to build the M11 motorway across the eastern boundary.[3]

Duxford was used as one of the locations for filming in 1989 for the Hollywood movie Memphis Belle,[12] with flying sequences flown from the airfield site.

Formula One teams used Duxford to conduct straight-line speed tests with an aim to develop aerodynamics. During a test in 2012, Marussia F1 driver María de Villota crashed heavily into the lift gate of the team transporter, and sustained serious injuries to her right eye and brain.[13] De Villota would later succumb to her injuries in 2013.[14][15]

IWM, American Air Museum and other employments

Today, RAF Duxford is owned by the Imperial War Museum (IWM) and is the site of the Imperial War Museum Duxford, and the American Air Museum. It also houses The Fighter Collection and the Historic Aircraft Collection, two private operators of airworthy vintage military aircraft.

The Imperial War Museum had been looking for a suitable site for the storage, restoration and eventual display of exhibits too large for its headquarters in London and obtained permission to use the airfield for this purpose. Cambridgeshire County Council joined with the IWM and the Duxford Aviation Society and in 1977 bought the runway to give the abandoned airfield a new lease of life. Also in 1977 the main runway was shortened from 6,000 ft (1,829 m) by about 1,200 ft (366 m) due to the construction of the M11 motorway, which passes along the eastern side of the airfield. The final aircraft to land at Duxford before the runway was shortened was Concorde test aircraft G-AXDN, now on display in the Airspace hangar.

In October 2008, an agreement was reached between Cambridgeshire County Council and the IWM, under which the runways and 146 acres (0.59 km2; 0.228 sq mi) of surrounding grassland would be sold to the museum for approximately £1.6 million.[16]

The site is home to Historic Flying Limited (Also known as The Aircraft Restoration Company).

The IWM and Cambridge University Gliding Club coexisted on the site for many years, but in 1991 increasing restrictions led the club to move to Gransden Lodge.

The site is sometimes used by Formula One teams such as Renault and Lotus for testing.[17] On Tuesday, 3 July 2012 María de Villota suffered an ultimately fatal accident while testing at the airfield for Marussia F1. The following day, team principal John Booth issued a statement which confirmed that the accident resulted in the loss of de Villota's right eye.[18] De Villota died in October 2013, as a result of long-term neurological damage sustained in the accident.[19]

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Citations

- "NATS - AIS - Home". Nats-uk.ead-it.com. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "UK Ordinary Aerodrome Licences - Licence No. P859" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- "BUILDING 45 (OFFICERS' MESS), Whittlesford - 1067839 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- "Duxford: Building 79 (Hangar 4)". Historic England. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

- "Royal Review Of The R.A.F.". The Times. No. 47110. 8 July 1935.

- "Duxford Squadrons". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- "Spitfire: 80 at 80". BAE Systems | International. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- Sarkar, Dilip (2020). Battle of Britain, 1940 : the finest hour's human cost. Barnsley. ISBN 978-1-5267-7594-8. OCLC 1156321027.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "What Was The 'Dowding System'?". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- "Duxford". American Air Museum in Britain. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "79th Service Group". American Air Museum in Britain. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "Memphis Belle (1990) - Filming Locations - IMDb". IMDb.com. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "F1 test driver De Villota loses eye after accident". Yahoo Eurosport UK. 4 July 2012.

- "Hallan el cuerpo sin vida de María de Villota en un hotel de Sevilla" [Found the lifeless body of María de Villota in a hotel in Seville]. ABC (in Spanish). 11 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- "Maria De Villota death linked to 2012 crash injuries, family told". BBC Sport. 12 October 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Duxford Deal is Run-A-Way Success". Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "IWM Duxford | Imperial War Museums". Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- "F1: Marussia Confirms de Villota in 'Critical but Stable' Condition". Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "Maria De Villota died from 2012 crash injuries, family told". BBC Sport. 12 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

Bibliography

- Freeman, Roger A., Airfields of the Eighth, Then And Now, 1978

- Maurer Maurer, Air Force Combat Units of World War II, Office of Air Force History, 1983

- USAAS-USAAC-USAAF-USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers--1908 to present

- USAAF Duxford Airfield, Station 357 Archived 13 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- 78th Fighter Group on Littlefriends.co.uk

External links

- Imperial War Museum Duxford

- American Air Museum Duxford

- Duxford Aviation Society, the volunteer organisation of the IWM Duxford.

- Imperial War Museum, Duxford - private photo website

- Website of the 78th Fighter Group

- RAF Duxford photo gallery

- A History of the Cambridge Gliding Club

- Duxford Pilot Group - GA flying group