Dvulikiaspis

Dvulikiaspis is a genus of chasmataspidid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of the single and type species, D. menneri, have been discovered in deposits of the Early Devonian period (Lochkovian epoch) in the Krasnoyarsk Krai, Siberia, Russia. The name of the genus is composed by the Russian word двуликий (dvulikij), meaning "two-faced", and the Ancient Greek word ἀσπίς (aspis), meaning "shield". The species name honors the discoverer of the holotype of Dvulikiaspis, Vladimir Vasilyevich Menner.

| Dvulikiaspis Temporal range: Lochkovian, | |

|---|---|

| |

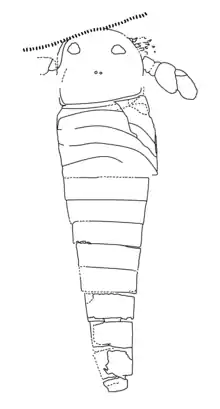

| Interpretive drawing of PIN 1271/2, the holotype of Dvulikiaspis menneri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Clade: | Dekatriata |

| Order: | †Chasmataspidida |

| Family: | †Diploaspididae |

| Genus: | †Dvulikiaspis Marshall et al., 2014 |

| Type species | |

| †Dvulikiaspis menneri Novojilov, 1959 | |

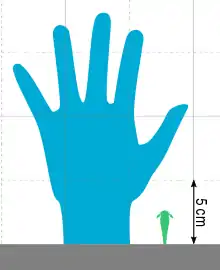

Its prosoma (head) was subquadrate (almost square) to parabolic (nearly U-shaped), with (bean-shaped) to subovate (nearly oval) eyes and surrounded by a marginal rim. The abdomen was composed by a fused buckler and a postabdomen that occupied most of the body length, while the telson (the posteriormost division of the body) was small and semicircular in shape. The appendages (limbs) were uniform. The sixth and last pair of them had a paddle-like shape and was placed in front of the midpoint of the prosoma. The largest specimen was 2.64 centimetres (1.04 inches) long.

The first fossil was described in 1959 as a new species of the eurypterid Stylonurus, while the other two were discovered in 1974. It would not be until 2014 when D. menneri was recognized as a chasmataspidid genus, being placed in the family Diploaspididae. However, Dvulikiaspis was similar to Loganamaraspis and especially Hoplitaspis, with which it could form a new separate family of chasmataspidids.

Description

Like the other chasmataspidids, D. menneri was a small arthropod. The biggest specimen, PIN 5116/1, reached a total length of 2.64 centimetres (1.04 inches). This size is, however, notable among diploaspidids.[1]

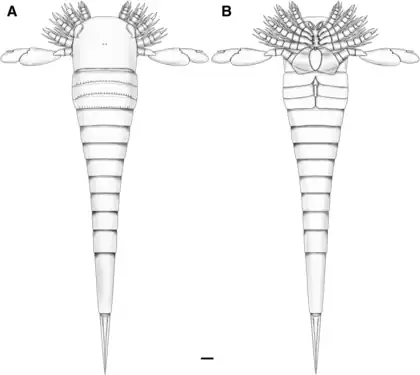

The prosoma (head) was subquadrate (almost square) to parabolic (nearly U-shaped), with a carapace (dorsal plate of the prosoma) rather vaulted and somewhat rounded anteriorly and laterally and flat medianly and posteriorly. It was surrounded by a marginal rim that tapered backwards to the sides. The largest preserved prosoma had a length of 0.5 cm (2 in). The eyes were large and reniform (bean-shaped) to subovate (nearly oval), placed between the sides and middle of the carapace. The ocelli (simple eye-like sensory organs) were positioned in the center of the prosoma.[1]

As in the rest of the chasmataspidids, its opisthosoma (abdomen) was composed of a preabdomen (segments 1 to 4) and a postabdomen (segments 5 to 13), in Dvulikiaspis with very slight first order differentiation (that is, both parts little separated from each other). The segments in general were wide rectangles with almost straight boundaries, narrowing slightly posteriorly. The microtergite (the short first tergite, dorsal half of the segment) was conformed to the posterior margin of the prosoma. The second to fourth segments were merged into a weakly expressed "buckler", which was wide rectangular with rounded lateral edges and narrow-angled shoulders (anterolateral "extensions" of the buckler). In the postabdomen, segments 11 to 13 were somewhat longer than the previous ones. Each tergite carried an articular surface (joint) on its front, interpreted to represent arthrodial membranes (plane joints),[1] which were a smooth and flattened facet, with a slight posterior ridge. These joints are identical to those of eurypterids and arachnids, and are considered homologous.[2] The telson (the posteriormost division of the body) was small and semicircular, measuring 0.09 cm (0.036 in) in length.[1]

The appendages (limbs) were almost parallel and of a similar length, being uniform and pediform (foot-like). There was a small progressive increase in length until the marginally shorter fifth pair. The podomeres (segments of the appendages) were differentiated by a straight line and narrowed towards the distal end. The second and third pair of appendages had five distal podomeres (podomeres that were not underneath the prosoma) while the fourth and fifth, four. The sixth and last pair of appendages of Dvulikiaspis are among the best known in Chasmataspidida. They were modified into a "paddle" ubicated in front of the midsection of the prosoma. Although only five podomeres are known, it is possible that the sixth appendage of Dvulikiaspis had eight. The chelicerae (first pair of appendages) are not known.[1]

History of research

Dvulikiaspis was originally described in 1959 as a species of the eurypterid genus Stylonurus, S. menneri, based on one single nearly complete specimen, PIN 1271/2 (housed at the Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow). It was found in deposits near the Imangda River at the southwest of the Taymyr Peninsula, near Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai (Russia, then the Soviet Union). The specific name menneri honors the Russian paleontologist and geologist Vladimir Vasilyevich Menner, who discovered the fossil in 1956. He sent it to the Russian paleontologist Nestor Ivanovich Novojilov, who erected the species.[3] To date, his description is considered inaccurate, inexhaustive and based only on the best preserved material.[1] Novojilov reported the presence of paired tubercles in the center of the second and fourth to sixth tergites of S. menneri, and he compared this new species with the Scottish eurypterid Lamontopterus knoxae (then also part of Stylonurus).[3]

Based on these tubercles, Novojilov would later assign S. menneri to the eurypterid genus Tylopterella, with whom it shared this characteristic. The paired tubercles, however, were doubtfully present in the holotype.[2] Two new specimens, PIN 5116/1 (a nearly complete opisthosoma) and PIN 5116/3 (a poorly preserved dorsal fossil), were found in 1974 on an expedition by Yu. N. Mokrousov, but they were not described. They were found in the Upper Zub Formation-Lower Kureika Formation, in the Krasnoyarsk Krai.[1] In 2011, the British geologist and paleobiologist James C. Lamsdell noted that by the presence of a paddle-like sixth appendage, three-segmented fused buckler and nine-segmented postabdomen, T. menneri could in fact represent a chasmataspidid, questioning the position of T. menneri in Tylopterella and Eurypterida.[2]

In 2014, the paleontologists David J. Marshall, Lamsdell, Evgeniy S. Shpinev and Simon J. Braddy recognized T. menneri as a new separate genus of chasmataspidid due to its body size and position of the prosomal appendages, specially the sixth appendage in the anterior half of the prosoma. They also described the two specimens collected in 1974, determining that all known material of this genus was subject to taphonomic distortion (that is, defects product of the fossilization of the organism). They named it Dvulikiaspis, which is composed of the Russian word двуликий (dvulikij, "two-faced", referring to the long-lasting misidentification of D. menneri) and the Ancient Greek suffix ἀσπίς (aspis, "shield"), being translated as "two-faced shield". They also noted that features such as the almost straight segment boundaries were shared with another chasmataspidid, Loganamaraspis, although the latter probably did not have a paddle-like sixth appendage.[1]

Classification

Dvulikiaspis is classified as part of the family Diploaspididae, one of the two families in the order Chasmataspidida. It includes one only species, D. menneri, from the Early Devonian of Siberia, Russia.[4]

D. menneri was originally recognized as a species of Stylonurus in 1959,[3] being moved to Tylopterella in 1962 due to the apparent presence of paired tubercles in the tergites. Both conclusions, done by Novojilov, have been criticized. Lamsdell already commented the possibility that D. menneri could represent a chasmataspidid in 2011.[2] This was demonstrated in 2014, when it was redescribed as a new genus of chasmataspidid and removed from Eurypterida, noting its distinction with other diploaspidids and suggesting a relationship with Loganamaraspis.[1] In 2019, during the description of the new Ordovician chasmataspidid Hoplitaspis hiawathai, it was suggested that Dvulikiaspis, Hoplitaspis and Loganamaraspis could represent a new family separated from Diploaspididae. These genera share the proportionality of the body (the postabdomen comprises the majority of the body length), a poorly differentiated buckler and a paddle projecting in front of the midpoint of the prosoma, although this is not certain in Loganamaraspis. However, the creation of a new family was not considered correct at the moment and all three genera currently remain in Diploaspididae, which is considered pending a more extensive revision.[5]

The cladogram below is based on a larger study (simplified to only show chasmataspidids) from 2015 carried out by the paleontologists Paul A. Selden, Lamsdell and Liu Qi, expanded to include the species Diploaspis praecursor, described in 2017. It showcases the phylogenetic relationships within Chasmataspidida.[6]

| Chasmataspidida |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Fossils of Dvulikiaspis have been discovered in Early Devonian (Lochkovian) deposits of Taymyria in Siberia, Russia.[1] D. menneri has been found alongside specimens of the chasmataspidids Heteroaspis stoermeri and Skrytyaspis andersoni, as well as the possible prosomapod Borchgrevinkium taimyrensis and indeterminate species of eurypterids like Acutiramus. The lithology (physical characteristics of the rocks) of the place near the Imangda River has been described as gypsiferous (with gypsum), dolomitic (with dolomite) and with dark gray marl.[3][7] The fossils were collected 60 metres below the Early Devonian-Middle Devonian boundary. The lithology of the Upper Zub Formation-Lower Kureika Formation was not much different, also containing dolomitic marl with gypsum. The chasmataspidids remains were collected at between 307 m and 308 m. Here, D. menneri has been found with fossils of S. andersoni and the eurypterids Pterygotus and Parahughmilleria hefteri.[1]

References

- Marshall, David J.; Lamsdell, James C.; Shpinev, Evgeniy S.; Braddy, Simon J. (2014). "A diverse chasmataspidid (Arthropoda: Chelicerata) fauna from the Early Devonian (Lochkovian) of Siberia". Palaeontology. 57 (3): 631–655. doi:10.1111/pala.12080. S2CID 84434367.

- Lamsdell, James C. (2011). "The eurypterid Stoermeropterus conicus from the lower Silurian of the Pentland Hills, Scotland". Monograph of the Palaeontographical Society. 165 (636): 1–84. doi:10.1080/25761900.2022.12131816. ISSN 0269-3445. S2CID 251107327.

- Novojilov, Nestor I. (1959). "Mérostomates du Dévonien inférieur et moyen de Sibérie". Annales de la Société géologique du Nord (in French). 78: 243–258.

- Dunlop, J. A.; Penney, D.; Jekel, D. (2018). "A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives" (PDF). World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Gunderson, Gerald O.; Meyer, Ronald C. (2019). "A common arthropod from the Late Ordovician Big Hill Lagerstätte (Michigan) reveals an unexpected ecological diversity within Chasmataspidida". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 19 (8): 1–24. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1329-4. PMC 6325806. PMID 30621579.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2017). "The first diploaspidid (Chelicerata: Chasmataspidida) from North America (Silurian, Bertie Group, New York State) is the oldest species of Diploaspis". Geological Magazine. 154 (1): 175–180. Bibcode:2017GeoM..154..175L. doi:10.1017/S0016756816000662. S2CID 85560431.

- "Merostomata, Lower Devonian, Imaigda river: Early/Lower Devonian, Russian Federation". The Paleobiology Database.