Dynamic Motion

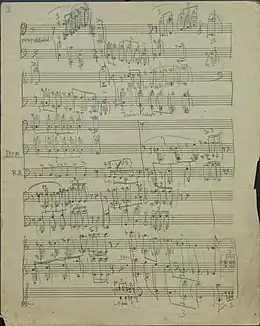

American composer Henry Cowell wrote one of his first surviving piano pieces, Dynamic Motion (HC 213), in 1916.[1][2] It is known as one of the first pieces in the history of music to utilize violent tone clusters for the keyboard. It requires the performer to use various limbs to play massive secundal chords, and calls for keys to be held down without sounding to extend its dissonant cluster overtones via sympathetic resonance. Some of the clusters outlined in this piece are those written for fists, palms, and forearms.[3] The piece is also noted for its extended use of tuplets, featuring triplets, quintuplets, and sextuplets in the melody line.

History

While still a teenager and studying at the University of California, Berkeley, Cowell wrote the piano piece Dynamic Motion, his first important work to explore the possibilities of the tone cluster. He first presented the piece to his composition teacher, Charles Seeger. This glimpse at Henry's music struck Seeger with great force; he would say Cowell used, "commonplace materials in some compositions and new or unusual materials in others," and appreciated the piece's "superfluous title". They both knew he would have to deal with a hostile or apathetic audience if he were to perform the piece publicly, however. "We spent no small amount of time in planning assaults, in the form of concerts, upon New York, Paris, and Berlin, in which elbows, string-plucking, and fantastic titles figured largely."

Composition

He would later give the piece a futurist-infused programmatic meaning in future concerts, saying:

Dynamic Motion is a musical impression of the New York subway. The clamor in the subterranean darkness, the wireless-like crossing of many minds huddled together, and rushing along insanely under the earth, a touch of horror and jagged suspense, and then the far light in the tunnel and the dizzying jerk at the end. The subject of Dynamic Motion spreads like a disease through the music...[4]

Five Encores to Dynamic Motion

The following year, in 1917, Cowell wrote five encores for the piece to be played during his various concert tours.

Controversies and performances

Both Dynamic Motion and its encores have elicited outrage, confusion, and outright violence at his various concerts, with several notable incidents.

New York

On March 31, 1922, Cowell appeared as a guest in Carl Ruggles's lecture on modern music at the Whitney Studio Club in Greenwich Village, New York City.[5] Louise Vermont, writing in the Greenwich Villager, contributed this account:

Then [Ruggles] introduced an American composer, who, according to Mr. Ruggles, "had something original to say with guts in it," Mr. Henry Cowell. Cowell said it with a wallop. One piano sounded like six of them. People stood up and watched this little fellow while the rolling sound wrapped them round and overwhelmed them with its dynamic force. For a closing number Cowell played one of his amazing compositions which he calls Dynamic Motion. At the finish of it three women lay in a dead faint in the aisle and no less than ten men had refreshed themselves from the left hip.[6][7]

Leipzig

During his first tour in Europe, Cowell played at the famous Gewandhaus concert hall in Leipzig, Germany on October 15, 1923. Cowell received a notoriously hostile reception during this concert, with some modern musicologists and historians referring to the event as a turning point in Cowell's performing career.[8][9] As he progressed further into the concert, deliberately saving the loudest and most provocative pieces for last, the audience's reception became more and more audibly hostile. Gasps and screams were heard, and Cowell recalled hearing a man in the front rows threaten to physically remove him from the stage if he did not stop. While playing the fourth movement Antinomy from the Five Encores, he later recalled:

[...] the audience was yelling and stamping and clapping and hissing until I could hardly hear myself. They stood up during most of the performance and got as near to me and the piano as they could. [...] Some of those who disapproved my methods were so excited that they almost threatened me with physical violence. Those who liked the music restrained them.[10]

During this excitement, a gentleman jumped up from one of the front rows and shook his fist at Cowell and said, "Halten Sie uns für Idioten in Deutschland?" ("Do you take us for idiots in Germany?"), while others threw the concert's program notes and other paraphernalia at his face.[11][12] About a minute later, an angry group of audience members clambered onto the stage, with a second, more supportive group following. The two groups began shouting over and confronting one another, which eventually turned into a large physical confrontation and riot on the stage, after which the Leipzig police were promptly called. Cowell later recalled of the incident, "The police came onto the stage and arrested 20 young fellows, the audience being in an absolute state of hysteria — and I was still playing!"[10] As Cowell had no severe physical injuries, the Leipzig authorities decided not to admit him to the local medical facility. After the concert had concluded and the stage was cleared, Cowell was noticeably shaken and jittery as he took his bow for the audience that remained and left the hall.

In the days following, the local Leipzig press were incredibly harsh regarding Cowell, the performance, and his musical style more broadly. The Leipziger Abendpost called the event, "[...] such a meaningless strumming and such a repulsive hacking of the keyboard not only with hands, but also even with fists, forearms and elbows, that one must call it a coarse obscenity — to put it mildly — to offer such a cacophony to the public, who in the end took it as a joke."[13] The Leipziger Neuste-Nachrichten additionally referred to his techniques as "musical grotesqueries".[14]

Vienna

Cowell was already in Vienna for his debut on October 31, which drew over three-hundred audience members. This event was much more peaceful compared to the Leipzig incident, but still fraught with incidents. One man began to scream, “Schluss, Schluss!” (Stop, stop!), and would not be quiet when shushed by audience members, leading to an attempt to drown one other out with continuous catcalling.[15]

References

Citations

- Sachs (2012), p. 61.

- Rischitelli (2005), p. 48.

- Rischitelli (2005), p. 56-57.

- Sachs (2012), p. 83.

- Rischitelli (2005), p. 57.

- Lichtenwanger, pp. 49-50

- Sachs (2012), p. 196.

- Rischitelli (2005), p. 26.

- Anon. (30 November 1953). "Music: Pioneer at 56". Time. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- "Strong-Arm Pianist" Evening Mail (8 Feb 1924)

- Hicks, p. 190

- "Reminiscences of Henry Cowell" (16 Oct 1962) Columbia University Oral History Research Office

- Leipziger Abendpost (5 Nov 1923) Cited in Manion, p. 128

- "Music". Leipziger Neuste-Nachrichten (5 Nov 1923). Cited in Manion, p. 128.

- Sachs (2012), p. 117.

Sources

- Sachs, Joel (2012). Henry Cowell: A Man Made of Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510895-8.

- Rischitelli, Victor (2005). Henry Cowell and the Impact of his First European Tour. North Sydney: Australian Catholic University.

External links

- Dynamic Motion and Encores, HC 213: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Dynamic Motion (animated score) on YouTube

- Five Encores (animated score) on YouTube

.jpg.webp)