Spontaneous symmetry breaking

Spontaneous symmetry breaking is a spontaneous process of symmetry breaking, by which a physical system in a symmetric state spontaneously ends up in an asymmetric state.[1][2][3] In particular, it can describe systems where the equations of motion or the Lagrangian obey symmetries, but the lowest-energy vacuum solutions do not exhibit that same symmetry. When the system goes to one of those vacuum solutions, the symmetry is broken for perturbations around that vacuum even though the entire Lagrangian retains that symmetry.

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

| Statistical mechanics |

|---|

|

Overview

By definition, spontaneous symmetry breaking requires the existence of physical laws (e.g. quantum mechanics) which are invariant under a symmetry transformation (such as translation or rotation), so that any pair of outcomes differing only by that transformation have the same probability distribution. For example if measurements of an observable at any two different positions have the same probability distribution, the observable has translational symmetry.

Spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs when this relation breaks down, while the underlying physical laws remain symmetrical.

Conversely, in explicit symmetry breaking, if two outcomes are considered, the probability distributions of a pair of outcomes can be different. For example in an electric field, the forces on a charged particle are different in different directions, so the rotational symmetry is explicitly broken by the electric field which does not have this symmetry.

Phases of matter, such as crystals, magnets, and conventional superconductors, as well as simple phase transitions can be described by spontaneous symmetry breaking. Notable exceptions include topological phases of matter like the fractional quantum Hall effect.

Typically, when spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs, the observable properties of the system change in multiple ways. For example the density, compressibility, coefficient of thermal expansion, and specific heat will be expected to change when a liquid becomes a solid.

Examples

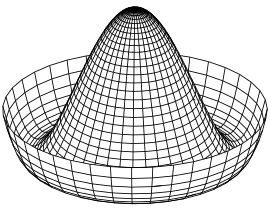

Sombrero potential

Consider a symmetric upward dome with a trough circling the bottom. If a ball is put at the very peak of the dome, the system is symmetric with respect to a rotation around the center axis. But the ball may spontaneously break this symmetry by rolling down the dome into the trough, a point of lowest energy. Afterward, the ball has come to a rest at some fixed point on the perimeter. The dome and the ball retain their individual symmetry, but the system does not.[4]

In the simplest idealized relativistic model, the spontaneously broken symmetry is summarized through an illustrative scalar field theory. The relevant Lagrangian of a scalar field , which essentially dictates how a system behaves, can be split up into kinetic and potential terms,

-

(1)

It is in this potential term that the symmetry breaking is triggered. An example of a potential, due to Jeffrey Goldstone[5] is illustrated in the graph at the left.

-

.

(2)

This potential has an infinite number of possible minima (vacuum states) given by

-

.

(3)

for any real θ between 0 and 2π. The system also has an unstable vacuum state corresponding to Φ = 0. This state has a U(1) symmetry. However, once the system falls into a specific stable vacuum state (amounting to a choice of θ), this symmetry will appear to be lost, or "spontaneously broken".

In fact, any other choice of θ would have exactly the same energy, and the defining equations respect the symmetry but the ground state (vacuum) of the theory breaks the symmetry, implying the existence of a massless Nambu–Goldstone boson, the mode running around the circle at the minimum of this potential, and indicating there is some memory of the original symmetry in the Lagrangian.[6][7]

Other examples

- For ferromagnetic materials, the underlying laws are invariant under spatial rotations. Here, the order parameter is the magnetization, which measures the magnetic dipole density. Above the Curie temperature, the order parameter is zero, which is spatially invariant, and there is no symmetry breaking. Below the Curie temperature, however, the magnetization acquires a constant nonvanishing value, which points in a certain direction (in the idealized situation where we have full equilibrium; otherwise, translational symmetry gets broken as well). The residual rotational symmetries which leave the orientation of this vector invariant remain unbroken, unlike the other rotations which do not and are thus spontaneously broken.

- The laws describing a solid are invariant under the full Euclidean group, but the solid itself spontaneously breaks this group down to a space group. The displacement and the orientation are the order parameters.

- General relativity has a Lorentz symmetry, but in FRW cosmological models, the mean 4-velocity field defined by averaging over the velocities of the galaxies (the galaxies act like gas particles at cosmological scales) acts as an order parameter breaking this symmetry. Similar comments can be made about the cosmic microwave background.

- For the electroweak model, as explained earlier, a component of the Higgs field provides the order parameter breaking the electroweak gauge symmetry to the electromagnetic gauge symmetry. Like the ferromagnetic example, there is a phase transition at the electroweak temperature. The same comment about us not tending to notice broken symmetries suggests why it took so long for us to discover electroweak unification.

- In superconductors, there is a condensed-matter collective field ψ, which acts as the order parameter breaking the electromagnetic gauge symmetry.

- Take a thin cylindrical plastic rod and push both ends together. Before buckling, the system is symmetric under rotation, and so visibly cylindrically symmetric. But after buckling, it looks different, and asymmetric. Nevertheless, features of the cylindrical symmetry are still there: ignoring friction, it would take no force to freely spin the rod around, displacing the ground state in time, and amounting to an oscillation of vanishing frequency, unlike the radial oscillations in the direction of the buckle. This spinning mode is effectively the requisite Nambu–Goldstone boson.

- Consider a uniform layer of fluid over an infinite horizontal plane. This system has all the symmetries of the Euclidean plane. But now heat the bottom surface uniformly so that it becomes much hotter than the upper surface. When the temperature gradient becomes large enough, convection cells will form, breaking the Euclidean symmetry.

- Consider a bead on a circular hoop that is rotated about a vertical diameter. As the rotational velocity is increased gradually from rest, the bead will initially stay at its initial equilibrium point at the bottom of the hoop (intuitively stable, lowest gravitational potential). At a certain critical rotational velocity, this point will become unstable and the bead will jump to one of two other newly created equilibria, equidistant from the center. Initially, the system is symmetric with respect to the diameter, yet after passing the critical velocity, the bead ends up in one of the two new equilibrium points, thus breaking the symmetry.

.png.webp)

- The two-balloon experiment is an example of spontaneous symmetry breaking when both balloons are initially inflated to the local maximum pressure. When some air flows from one balloon into the other, the pressure in both balloons will drop, making the system more stable in the asymmetric state.

In particle physics

In particle physics, the force carrier particles are normally specified by field equations with gauge symmetry; their equations predict that certain measurements will be the same at any point in the field. For instance, field equations might predict that the mass of two quarks is constant. Solving the equations to find the mass of each quark might give two solutions. In one solution, quark A is heavier than quark B. In the second solution, quark B is heavier than quark A by the same amount. The symmetry of the equations is not reflected by the individual solutions, but it is reflected by the range of solutions.

An actual measurement reflects only one solution, representing a breakdown in the symmetry of the underlying theory. "Hidden" is a better term than "broken", because the symmetry is always there in these equations. This phenomenon is called spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) because nothing (that we know of) breaks the symmetry in the equations.[8]: 194–195 By the nature of spontaneous symmetry breaking, different portions of the early Universe would break symmetry in different directions, leading to topological defects, such as two-dimensional domain walls, one-dimensional cosmic strings, zero-dimensional monopoles, and/or textures, depending on the relevant homotopy group and the dynamics of the theory. For example, Higgs symmetry breaking may have created primordial cosmic strings as a byproduct. Hypothetical GUT symmetry-breaking generically produces monopoles, creating difficulties for GUT unless monopoles (along with any GUT domain walls) are expelled from our observable Universe through cosmic inflation.[9]

Chiral symmetry

Chiral symmetry breaking is an example of spontaneous symmetry breaking affecting the chiral symmetry of the strong interactions in particle physics. It is a property of quantum chromodynamics, the quantum field theory describing these interactions, and is responsible for the bulk of the mass (over 99%) of the nucleons, and thus of all common matter, as it converts very light bound quarks into 100 times heavier constituents of baryons. The approximate Nambu–Goldstone bosons in this spontaneous symmetry breaking process are the pions, whose mass is an order of magnitude lighter than the mass of the nucleons. It served as the prototype and significant ingredient of the Higgs mechanism underlying the electroweak symmetry breaking.

Higgs mechanism

The strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces can all be understood as arising from gauge symmetries, which is a redundancy in the description of the symmetry. The Higgs mechanism, the spontaneous symmetry breaking of gauge symmetries, is an important component in understanding the superconductivity of metals and the origin of particle masses in the standard model of particle physics. The term "spontaneous symmetry breaking" is a misnomer here as Elitzur's theorem states that local gauge symmetries can never be spontaneously broken. Rather, after gauge fixing, the global symmetry (or redundancy) can be broken in a manner formally resembling spontaneous symmetry breaking. One important consequence of the distinction between true symmetries and gauge symmetries, is that the massless Nambu–Goldstone resulting from spontaneous breaking of a gauge symmetry are absorbed in the description of the gauge vector field, providing massive vector field modes, like the plasma mode in a superconductor, or the Higgs mode observed in particle physics.

In the standard model of particle physics, spontaneous symmetry breaking of the SU(2) × U(1) gauge symmetry associated with the electro-weak force generates masses for several particles, and separates the electromagnetic and weak forces. The W and Z bosons are the elementary particles that mediate the weak interaction, while the photon mediates the electromagnetic interaction. At energies much greater than 100 GeV, all these particles behave in a similar manner. The Weinberg–Salam theory predicts that, at lower energies, this symmetry is broken so that the photon and the massive W and Z bosons emerge.[10] In addition, fermions develop mass consistently.

Without spontaneous symmetry breaking, the Standard Model of elementary particle interactions requires the existence of a number of particles. However, some particles (the W and Z bosons) would then be predicted to be massless, when, in reality, they are observed to have mass. To overcome this, spontaneous symmetry breaking is augmented by the Higgs mechanism to give these particles mass. It also suggests the presence of a new particle, the Higgs boson, detected in 2012.

Superconductivity of metals is a condensed-matter analog of the Higgs phenomena, in which a condensate of Cooper pairs of electrons spontaneously breaks the U(1) gauge symmetry associated with light and electromagnetism.

Dynamical symmetry breaking

Dynamical symmetry breaking (DSB) is a special form of spontaneous symmetry breaking in which the ground state of the system has reduced symmetry properties compared to its theoretical description (i.e., Lagrangian).

Dynamical breaking of a global symmetry is a spontaneous symmetry breaking, which happens not at the (classical) tree level (i.e., at the level of the bare action), but due to quantum corrections (i.e., at the level of the effective action).

Dynamical breaking of a gauge symmetry is subtler. In conventional spontaneous gauge symmetry breaking, there exists an unstable Higgs particle in the theory, which drives the vacuum to a symmetry-broken phase (i.e, electroweak interactions.) In dynamical gauge symmetry breaking, however, no unstable Higgs particle operates in the theory, but the bound states of the system itself provide the unstable fields that render the phase transition. For example, Bardeen, Hill, and Lindner published a paper that attempts to replace the conventional Higgs mechanism in the standard model by a DSB that is driven by a bound state of top-antitop quarks. (Such models, in which a composite particle plays the role of the Higgs boson, are often referred to as "Composite Higgs models".)[11] Dynamical breaking of gauge symmetries is often due to creation of a fermionic condensate — e.g., the quark condensate, which is connected to the dynamical breaking of chiral symmetry in quantum chromodynamics. Conventional superconductivity is the paradigmatic example from the condensed matter side, where phonon-mediated attractions lead electrons to become bound in pairs and then condense, thereby breaking the electromagnetic gauge symmetry.

In condensed matter physics

Most phases of matter can be understood through the lens of spontaneous symmetry breaking. For example, crystals are periodic arrays of atoms that are not invariant under all translations (only under a small subset of translations by a lattice vector). Magnets have north and south poles that are oriented in a specific direction, breaking rotational symmetry. In addition to these examples, there are a whole host of other symmetry-breaking phases of matter — including nematic phases of liquid crystals, charge- and spin-density waves, superfluids, and many others.

There are several known examples of matter that cannot be described by spontaneous symmetry breaking, including: topologically ordered phases of matter, such as fractional quantum Hall liquids, and spin-liquids. These states do not break any symmetry, but are distinct phases of matter. Unlike the case of spontaneous symmetry breaking, there is not a general framework for describing such states.[12]

Continuous symmetry

The ferromagnet is the canonical system that spontaneously breaks the continuous symmetry of the spins below the Curie temperature and at h = 0, where h is the external magnetic field. Below the Curie temperature, the energy of the system is invariant under inversion of the magnetization m(x) such that m(x) = −m(−x). The symmetry is spontaneously broken as h → 0 when the Hamiltonian becomes invariant under the inversion transformation, but the expectation value is not invariant.

Spontaneously-symmetry-broken phases of matter are characterized by an order parameter that describes the quantity which breaks the symmetry under consideration. For example, in a magnet, the order parameter is the local magnetization.

Spontaneous breaking of a continuous symmetry is inevitably accompanied by gapless (meaning that these modes do not cost any energy to excite) Nambu–Goldstone modes associated with slow, long-wavelength fluctuations of the order parameter. For example, vibrational modes in a crystal, known as phonons, are associated with slow density fluctuations of the crystal's atoms. The associated Goldstone mode for magnets are oscillating waves of spin known as spin-waves. For symmetry-breaking states, whose order parameter is not a conserved quantity, Nambu–Goldstone modes are typically massless and propagate at a constant velocity.

An important theorem, due to Mermin and Wagner, states that, at finite temperature, thermally activated fluctuations of Nambu–Goldstone modes destroy the long-range order, and prevent spontaneous symmetry breaking in one- and two-dimensional systems. Similarly, quantum fluctuations of the order parameter prevent most types of continuous symmetry breaking in one-dimensional systems even at zero temperature. (An important exception is ferromagnets, whose order parameter, magnetization, is an exactly conserved quantity and does not have any quantum fluctuations.)

Other long-range interacting systems, such as cylindrical curved surfaces interacting via the Coulomb potential or Yukawa potential, have been shown to break translational and rotational symmetries.[13] It was shown, in the presence of a symmetric Hamiltonian, and in the limit of infinite volume, the system spontaneously adopts a chiral configuration — i.e., breaks mirror plane symmetry.

Generalisation and technical usage

For spontaneous symmetry breaking to occur, there must be a system in which there are several equally likely outcomes. The system as a whole is therefore symmetric with respect to these outcomes. However, if the system is sampled (i.e. if the system is actually used or interacted with in any way), a specific outcome must occur. Though the system as a whole is symmetric, it is never encountered with this symmetry, but only in one specific asymmetric state. Hence, the symmetry is said to be spontaneously broken in that theory. Nevertheless, the fact that each outcome is equally likely is a reflection of the underlying symmetry, which is thus often dubbed "hidden symmetry", and has crucial formal consequences. (See the article on the Goldstone boson.)

When a theory is symmetric with respect to a symmetry group, but requires that one element of the group be distinct, then spontaneous symmetry breaking has occurred. The theory must not dictate which member is distinct, only that one is. From this point on, the theory can be treated as if this element actually is distinct, with the proviso that any results found in this way must be resymmetrized, by taking the average of each of the elements of the group being the distinct one.

The crucial concept in physics theories is the order parameter. If there is a field (often a background field) which acquires an expectation value (not necessarily a vacuum expectation value) which is not invariant under the symmetry in question, we say that the system is in the ordered phase, and the symmetry is spontaneously broken. This is because other subsystems interact with the order parameter, which specifies a "frame of reference" to be measured against. In that case, the vacuum state does not obey the initial symmetry (which would keep it invariant, in the linearly realized Wigner mode in which it would be a singlet), and, instead changes under the (hidden) symmetry, now implemented in the (nonlinear) Nambu–Goldstone mode. Normally, in the absence of the Higgs mechanism, massless Goldstone bosons arise.

The symmetry group can be discrete, such as the space group of a crystal, or continuous (e.g., a Lie group), such as the rotational symmetry of space. However, if the system contains only a single spatial dimension, then only discrete symmetries may be broken in a vacuum state of the full quantum theory, although a classical solution may break a continuous symmetry.

Nobel Prize

On October 7, 2008, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physics to three scientists for their work in subatomic physics symmetry breaking. Yoichiro Nambu, of the University of Chicago, won half of the prize for the discovery of the mechanism of spontaneous broken symmetry in the context of the strong interactions, specifically chiral symmetry breaking. Physicists Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa, of Kyoto University, shared the other half of the prize for discovering the origin of the explicit breaking of CP symmetry in the weak interactions.[14] This origin is ultimately reliant on the Higgs mechanism, but, so far understood as a "just so" feature of Higgs couplings, not a spontaneously broken symmetry phenomenon.

See also

- Autocatalytic reactions and order creation

- Catastrophe theory

- Chiral symmetry breaking

- CP-violation

- Fermi ball

- Gauge gravitation theory

- Goldstone boson

- Grand unified theory

- Higgs mechanism

- Higgs boson

- Higgs field (classical)

- Irreversibility

- Magnetic catalysis of chiral symmetry breaking

- Mermin–Wagner theorem

- Norton's dome

- Second-order phase transition

- Spontaneous absolute asymmetric synthesis in chemistry

- Symmetry breaking

- Tachyon condensation

- 1964 PRL symmetry breaking papers

Notes

- ^ Note that (as in fundamental Higgs driven spontaneous gauge symmetry breaking) the term "symmetry breaking" is a misnomer when applied to gauge symmetries.

References

- Miransky, Vladimir A. (1993). Dynamical Symmetry Breaking in Quantum Field Theories. World Scientific. p. 15. ISBN 9810215584.

- Arodz, Henryk; Dziarmaga, Jacek; Zurek, Wojciech Hubert, eds. (30 November 2003). Patterns of Symmetry Breaking. Springer. p. 141. ISBN 9781402017452.

- Cornell, James, ed. (21 November 1991). Bubbles, Voids and Bumps in Time: The New Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780521426732.

- Edelman, Gerald M. (1992). Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Mind. New York: BasicBooks. p. 203.

- Goldstone, J. (1961). "Field theories with " Superconductor " solutions". Il Nuovo Cimento. 19 (1): 154–164. Bibcode:1961NCim...19..154G. doi:10.1007/BF02812722. S2CID 120409034.

- Muñoz-Vega, R.; García-Quiroz, A.; López-Chávez, Ernesto; Salinas-Hernández, Encarnación (2012). "Spontaneous symmetry breakdown in non-relativistic quantum mechanics". American Journal of Physics. 80 (10): 891–897. arXiv:1205.4773. Bibcode:2012AmJPh..80..891M. doi:10.1119/1.4739927. S2CID 119131875.

- Kibble, T W B. (2015). "History of electroweak symmetry breaking". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 626 (1): 012001. arXiv:1502.06276. Bibcode:2015JPhCS.626a2001K. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/626/1/012001. S2CID 119290021.

- Steven Weinberg (20 April 2011). Dreams of a Final Theory: The Scientist's Search for the Ultimate Laws of Nature. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-78786-6.

- Jeannerot, Rachel; Rocher, Jonathan; Sakellariadou, Mairi (24 November 2003). "How generic is cosmic string formation in supersymmetric grand unified theories". Physical Review D. 68 (10): 103514. arXiv:hep-ph/0308134. Bibcode:2003PhRvD..68j3514J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.68.103514.

- A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking, Bantam; 10th anniversary edition (1998). pp. 73–74.

- William A. Bardeen; Christopher T. Hill; Manfred Lindner (1990). "Minimal dynamical symmetry breaking of the standard model". Physical Review D. 41 (5): 1647–1660. Bibcode:1990PhRvD..41.1647B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.41.1647. PMID 10012522.

- Chen, Xie; Gu, Zheng-Cheng; Wen, Xiao-Gang (2010). "Local unitary transformation, long-range quantum entanglement, wave function renormalization, and topological order". Phys. Rev. B. 82 (15): 155138. arXiv:1004.3835. Bibcode:2010PhRvB..82o5138C. doi:10.1103/physrevb.82.155138. S2CID 14593420.

- Kohlstedt, K.L.; Vernizzi, G.; Solis, F.J.; Olvera de la Cruz, M. (2007). "Spontaneous Chirality via Long-range Electrostatic Forces". Physical Review Letters. 99 (3): 030602. arXiv:0704.3435. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99c0602K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.030602. PMID 17678276. S2CID 37983980.

- The Nobel Foundation. "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2008". nobelprize.org. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

External links

- For a pedagogic introduction to electroweak symmetry breaking with step by step derivations, not found in texts, of many key relations, see http://www.quantumfieldtheory.info/Electroweak_Sym_breaking.pdf

- Spontaneous symmetry breaking

- Physical Review Letters – 50th Anniversary Milestone Papers

- In CERN Courier, Steven Weinberg reflects on spontaneous symmetry breaking

- Englert–Brout–Higgs–Guralnik–Hagen–Kibble Mechanism on Scholarpedia

- History of Englert–Brout–Higgs–Guralnik–Hagen–Kibble Mechanism on Scholarpedia

- The History of the Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble development of the Theory of Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking and Gauge Particles

- International Journal of Modern Physics A: The History of the Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble development of the Theory of Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking and Gauge Particles

- Guralnik, G S; Hagen, C R and Kibble, T W B (1967). Broken Symmetries and the Goldstone Theorem. Advances in Physics, vol. 2 Interscience Publishers, New York. pp. 567–708 ISBN 0-470-17057-3

- Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking in Gauge Theories: a Historical Survey

- The Royal Society Publishing: Spontaneous symmetry breaking in gauge theories

- University of Cambridge, David Tong: Lectures on Quantum Field Theory for masters level students.