Old Latin

Old Latin, also known as Early Latin or Archaic Latin (Classical Latin: prīsca Latīnitās, lit. 'ancient Latinity'), was the Latin language in the period before 75 BC, i.e. before the age of Classical Latin.[1] It descends from a common Proto-Italic language; Latino-Faliscan is likely a separate branch from Osco-Umbrian with possible further relation to other Italic languages and to Celtic; e.g. the Italo-Celtic hypothesis.

| Old Latin | |

|---|---|

| Archaic Latin | |

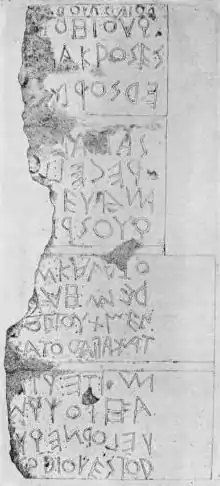

The Duenos inscription, one of the earliest Old Latin texts | |

| Native to | Latium, later the Roman Kingdom and Republic |

| Region | Italy |

| Ethnicity | Latins, Romans |

| Era | Attested since 7th century BC. Developed into Vulgar Latin as colloquial form, and Literary Latin as literary form, during the 1st century BC. |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Latin alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Rome |

| Regulated by | Schools of grammar and rhetoric |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

qbb | |

| Glottolog | oldl1238 |

Expansion of the Roman Republic during the 2nd century BC. Very little Latin is likely to have been spoken beyond the green area, and other languages were spoken even within it. | |

The use of "old", "early" and "archaic" has been standard in publications of Old Latin writings since at least the 18th century. The definition is not arbitrary, but the terms refer to spelling conventions and word forms not generally found in works written under the Roman Empire. This article presents some of the major differences.

The earliest known specimen of Latin seems to be on the Praeneste fibula. A new analysis done in 2011 declared it to be genuine "beyond any reasonable doubt"[2] and dating from the Orientalizing period, in the first half of the seventh century BC.[3] Other Old Latin inscriptions dated to either the late Roman Kingdom or early Roman Republic include the Lapis Niger stone, the Duenos Inscription on a kernos vase, and the Garigliano bowl of Bucchero type.

Philological constructs

The old-time language

The concept of Old Latin (Prisca Latinitas) is as old as the concept of Classical Latin – both labels date to at least as early as the late Roman Republic. In that period Cicero, along with others, noted that the language he used every day, presumably upper-class city Latin, included lexical items and phrases that were heirlooms from a previous time, which he called verborum vetustas prisca,[4] translated as "the old age/time of language".

In the classical period, Prisca Latinitas, Prisca Latina and other idioms using the adjective always meant these remnants of a previous language, which, in Roman philology, was taken to be much older in fact than it really was. Viri prisci, "old-time men", meant the population of Latium before the founding of Rome.

The four Latins of Isidore

In the Late Latin period, when Classical Latin was behind them, Latin- and Greek-speaking grammarians were faced with multiple phases, or styles, within the language. Isidore of Seville (c. 560 – 636) reports a classification scheme that had come into existence in or before his time: "the four Latins" ("Moreover, some people have said that there are four Latin languages"; "Latinas autem linguas quattuor esse quidam dixerunt").[5] They were:

- Prisca, spoken before the founding of Rome, when Janus and Saturn ruled Latium, to which period Isidore dated the Carmen Saliare

- Latina, dated from the time of king Latinus, in which period he placed the laws of the Twelve Tables

- Romana, essentially equal to Classical Latin

- Mixta, "mixed" Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin, known today as Late Latin.

This scheme persisted with little change for some thousand years after Isidore.

Old Latin

In 1874, John Wordsworth used this definition: "By Early Latin I understand Latin of the whole period of the Republic, which is separated very strikingly, both in tone and in outward form, from that of the Empire."[6]

Although the differences are striking and can be easily identified by Latin readers, they are not such as to cause a language barrier. Latin speakers of the empire had no reported trouble understanding Old Latin, except for the few texts that must date from the time of the kings, mainly songs. Thus, the laws of the Twelve Tables (5th century BC) from the early Republic were comprehensible, but the Carmen Saliare, probably written under Numa Pompilius (who traditionally reigned from 715 to 673 BC), was not entirely clear (and remains so). On the other hand, Polybius, a Greek historian of Rome who flourished in the late second century BC,[7] commented on "the first treaty between Rome and Carthage", (which he dated to 28 years before Xerxes I crossed into Greece; that is, in 508 BC) that "the ancient Roman language differs so much from the modern that it can only be partially made out, and that after much application by the most intelligent men".

There is no sharp distinction between Old Latin, as it was spoken for most of the Republic, and Classical Latin, but the earlier grades into the later. The end of the republic was too late a termination for compilers after Wordsworth; Charles Edwin Bennett said, "'Early Latin' is necessarily a somewhat vague term ... Bell, De locativi in prisca Latinitate vi et usu, Breslau, 1889,[8] sets the later limit at 75 BC. A definite date is really impossible, since archaic Latin does not terminate abruptly, but continues even down to imperial times."[9] Bennett's own date of 100 BC did not prevail; rather Bell's 75 BC became the standard as expressed in the four-volume Loeb Library and other major compendia. Over the 377 years from 452 to 75 BC, Old Latin evolved from texts partially comprehensible by classicists with study to being easily read by scholars.

Corpus

Old Latin authored works began in the 3rd century BC. These are complete or nearly complete works under their own name surviving as manuscripts copied from other manuscripts in whatever script was current at the time. There are also fragments of works quoted in other authors.

Many texts placed by various methods (painting, engraving, embossing) on their original media survive just as they were except for the ravages of time. Some of these were copied from other inscriptions. No inscription can be older than the introduction of the Greek alphabet into Italy but none survive from that early date. The imprecision of archaeological dating makes it impossible to assign a year to any one inscription, but the earliest survivals are probably from the 6th century BC. Some texts, however, that survive as fragments in the works of classical authors, had to have been composed earlier than the republic, in the time of the monarchy. These are listed below. Some authors, especially in recent texts, refer to the oldest Latin documents (7th–5th c. BCE) as Very Old Latin (VOL).[10]

Fragments and inscriptions

Notable Old Latin fragments with estimated dates include:

- The Carmen Saliare (chant put forward in classical times as having been sung by the Salian brotherhood formed by Numa Pompilius, approximate date 700 BC)

- The Praeneste fibula (date from first half of the seventh century BC.)

- The Tita Vendia vase (c. 620–600 BC)

- The Forum inscription (see illustration, c. 550 BC under the monarchy)

- The Duenos inscription (c. 500 BC)

- The Castor-Pollux dedication (c. 500 BC)

- The Garigliano Bowl (c. 500 BC)

- The Lapis Satricanus (early 5th century BC)

- The preserved fragments of the laws of the Twelve Tables (traditionally, 449 BC, attested much later)

- The Tibur pedestal (c. 400 BC)

- The Scipionum Elogia

- Epitaph of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus (consul 298 BC)

- Epitaph of Lucius Cornelius Scipio (consul 259 BC)

- Epitaph of Publius Cornelius Scipio P.f. P.n. Africanus (died about 170 BC)

- The Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus (186 BC)

- The Vase Inscription from Ardea

- The Corcolle Altar fragments

- The Carmen Arvale

- Altar to the Unknown Divinity (92 BC)

Works of literature

Authors:

- Lucius Livius Andronicus (c. 280/260 BC – c. 200 BC), translator, founder of Roman drama

- Gnaeus Naevius (c. 264–201 BC), dramatist, epic poet

- Titus Maccius Plautus (c. 254–184 BC), dramatist, composer of comedies

- Quintus Ennius (239 – c. 169 BC), poet

- Marcus Pacuvius (c. 220–130 BC), tragic dramatist, poet

- Statius Caecilius (220 – 168/166 BC), comic dramatist

- Publius Terentius Afer (195/185 – 159 BC), comic dramatist

- Marcus Porcius Cato (234–149 BC), orator, historian, topical writer

- Lucius Accius (170 – c. 86 BC), tragic dramatist, philologist

- Gaius Lucilius (c. 160s – 103/102 BC), satirist

- Quintus Lutatius Catulus (2nd century BC), public officer, epigrammatist

- Aulus Furius Antias (2nd century BC), poet

- Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo Vopiscus (130–87 BC), public officer, tragic dramatist

- Lucius Pomponius Bononiensis (2nd century BC), comic dramatist, satirist

- Lucius Cassius Hemina (2nd century BC), historian

- Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi (2nd century BC), historian

- Manius Manilius (2nd century BC), public officer, jurist

- Lucius Coelius Antipater (2nd century BC), jurist, historian

- Publius Sempronius Asellio (158 BC – after 91 BC), military officer, historian

- Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus (2nd century BC), jurist

- Lucius Afranius (2nd and 1st centuries BC), comic dramatist

- Titus Albucius (2nd and 1st centuries BC), orator

- Publius Rutilius Rufus (158 BC – after 78 BC), jurist

- Lucius Aelius Stilo Praeconinus (154–74 BC), philologist

- Quintus Claudius Quadrigarius (2nd and 1st centuries BC), historian

- Valerius Antias (2nd and 1st centuries BC), historian

- Lucius Cornelius Sisenna (121–67 BC), soldier, historian

- Quintus Cornificius (2nd and 1st centuries BC), rhetorician

Script

Old Latin surviving in inscriptions is written in various forms of the Etruscan alphabet as it evolved into the Latin alphabet. The writing conventions varied by time and place until classical conventions prevailed. A part of old inscriptions, texts in the original writing system have been lost or transcribed by later copyists.

Old Latin could be written from right to left (as were Etruscan and early Greek) or boustrophedon.[11]

Orthography

Some differences between old and classical Latin were of spelling only; pronunciation is thought to be essentially the same as in classical Latin:[12]

- Single for double consonants: Marcelus for Marcellus

- Double vowels for long vowels: aara for āra

- q for c before u: pequnia for pecunia

- c for g: Caius for Gaius

These differences did not necessarily run concurrently with each other and were not universal; that is, c was used for both c and g.

Phonology

Stress

Old Latin is thought to have had a strong stress on the first syllable of a word until about 250 BC. All syllables other than the first were unstressed and were subjected to greater amounts of phonological weakening. Starting around that year, the Classical Latin stress system began to develop. It passed through at least one intermediate stage, found in Plautus, in which the stress occurred on the fourth last syllable in four-syllable words with all short syllables.

Vowels and diphthongs

Most original PIE (Proto-Indo-European) diphthongs were preserved in stressed syllables, including /ai/ (later ae); /ei/ (later ī); /oi/ (later ū, or sometimes oe); /ou/ (from PIE /eu/ and /ou/; later ū).

The Old Latin diphthong ei evolves in stages: ei > ẹ̄ > ī. The intermediate sound ẹ̄ was simply written e but must have been distinct from the normal long vowel ē because ẹ̄ subsequently merged with ī while ē did not. It is generally thought that ẹ̄ was a higher sound than e (e.g. perhaps [eː] vs. [ɛː] during the time when both sounds existed). Even after the original vowel /ei/ had merged with ī, the old spelling ei continued to be used for a while, with the result that ei came to stand for ī and began to be used in the spelling of original occurrences of ī that did not evolve from ei (e.g. in the genitive singular -ī, which is always spelled -i in the oldest inscriptions but later on can be spelled either -i or -ei).

In unstressed syllables, *oi and *ai had already merged into ei by historic times (except for one possible occurrence of poploe for populī "people" in a late manuscript of one of the early songs). This eventually also evolved to ī.

Old Latin often had different short vowels from Classical Latin, reflecting sound changes that had not yet taken place. For example, the very early Duenos inscription has the form duenos "good", later found as duonos and still later bonus. A countervailing change wo > we occurred around 150 BC in certain contexts, and many earlier forms are found (e.g. earlier votō, voster, vorsus vs. later vetō, vester, versus).

Old Latin frequently preserves original PIE thematic case endings -os and -om (later -us and -um).

Consonants

Intervocalic /s/ (pronounced [z]) was preserved up to 350 BC or so, at which point it changed into /r/ (rhotacism). This rhotacism had implications for declension: early classical Latin, honos, honoris (from honos, honoses); later Classical (by analogy) honor, honoris ("honor"). Some Old Latin texts preserve /s/ in this position, such as the Carmen Arvale's lases for lares. Later instances of single /s/ between vowels are mostly due either to reduction of early /ss/ after long vowels or diphthongs; borrowings; or late reconstructions.

There are many unreduced clusters, e.g. iouxmentom (later iūmentum, "beast of burden"); losna (later lūna, "moon") < *lousna < */leuksnā/; cosmis (> cōmis, "courteous"); stlocum, acc. (> locum, "place").

Early du /dw/ becomes b: duenos > duonos > bonus "good"; duis > bis "twice"; duellom > bellum "war".

Final /d/ occurred in ablatives, such as puellād "from the girl" or campōd "from the field", later puellā and campō. In verb conjugation, the third-person ending -d later became -t, e.g. Old Latin faced > Classical facit.

Morphology

Nouns

Latin nouns have grammatical case, with an ending, or suffix, showing its use in the sentence: subject, predicate, etc. A case for a given word is formed by suffixing a case ending to a part of the word common to all its cases called a stem. Stems are classified by their last letters as vowel or consonant. Vowel stems are formed by adding a suffix to a shorter and more ancient segment called a root. Consonant stems are the root (roots end in consonants). The combination of the last letter of the stem and the case ending often results in an ending also called a case ending or termination. For example, the stem puella- receives a case ending -m to form the accusative case puellam in which the termination -am is evident.[14]

In Classical Latin textbooks the declensions are named from the letter ending the stem or First, Second, etc. to Fifth. A declension may be illustrated by a paradigm, or listing of all the cases of a typical word. This method is less often applied to Old Latin, and with less validity. In contrast to Classical Latin, Old Latin reflects the evolution of the language from an ancestor spoken in Latium. The endings are multiple. Their use depends on time and place. Any paradigm selected would be subject to these constraints and if applied to the language universally would give false constructs, hypothetical words not attested in the Old Latin corpus. Nevertheless, the endings are shown below by quasi-classical paradigms. Alternate endings from different stages of development are given, but they may not be attested for the word of the paradigm. For example, in the second declension, *campoe "fields" is unattested, but poploe "peoples" is attested.

The locative was a separate case in Old Latin but gradually became reduced in function, and the locative singular form eventually merged with the genitive singular by regular sound change. In the plural, the locative was captured by the ablative case in all Italic languages before Old Latin.[15]

First declension (a)

| puellā, –ās girl, maiden f. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | puellā, puellă | puellāī |

| Vocative | puella | puellai |

| Accusative | puellam | puellās |

| Genitive | puellās, puellāī, puellais | puellom, puellāsōm |

| Dative | puellāi | puelleis, puellābos |

| Ablative | puellād | |

| Locative | (Rōmai) | (Syrācūseis) |

The stems of nouns of this declension usually end in -ā and are typically feminine.[16] A nominative case ending of -s in a few masculines indicates the nominative singular case ending may have been originally -s: paricidas for later parricida, but the -s tended to get lost.[17] In the nominative plural, -ī replaced original -s as in the genitive singular.[18]

In the genitive singular, the -s was replaced with -ī from the second declension, the resulting diphthong shortening to -ai subsequently becoming -ae.[19] The original form is maintained in some formulas, e.g. pater familiās. The genitive plural ending -āsōm (classical -ārum following rhotacism), borrowed from the pronouns, began to overtake original -om.[18]

In the dative singular the final i is either long[20] or short.[21] The ending becomes -ae, -a (Feronia) or -e (Fortune).[20]

In the accusative singular, Latin regularly shortens a vowel before final m.[21]

In the ablative singular, -d was regularly lost after a long vowel.[21] In the dative and ablative plural, the -abos descending from Indo-European *-ābhos[22] is used for feminines only (deabus). *-ais > -eis > -īs is adapted from -ois of the o-declension.[23]

The vocative singular had inherited short -a. This later merged with the nominative singular when -ā was shortened to -ă.[21]

The locative case would not apply to such a meaning as puella, so Roma, which is singular, and Syracusae, which is plural, have been substituted. The locative plural has already merged with the -eis form of the ablative.

Second declension (o)

| campos, –ī field, plain m. |

saxom, –ī rock, stone n. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | campos | campei < campoi | saxom | saxā, saxă |

| Vocative | campe | saxă | ||

| Accusative | campom | campōs | saxom | saxā, saxă |

| Genitive | campī | campōm | saxī | saxōm |

| Dative | campō | campeis < campois | saxō | saxeis < saxois |

| Ablative | campōd | saxōd | ||

| Locative | campei | saxei | ||

The stems of the nouns of the o-declension end in ŏ deriving from the o-grade of Indo-European ablaut.[24] Classical Latin evidences the development ŏ > ŭ. Nouns of this declension are either masculine or neuter.

Nominative singulars ending in -ros or -ris syncopate the ending:[25] *agros > *agrs > *agers > *agerr > ager. (The form terr "three times" for later ter < *tris appears in Plautus.)

Many alternative spellings occur:

- As mentioned above, the sound change -ei > -ẹ̄ > -ī leads to many variations, including the reverse spelling ei for ī. This spelling eventually appears in the genitive singular as well, though -ī is earliest and the true ending; cf. populi Romanei, "of the Roman people."[26], with both spellings in the same inscription.

- Likewise, the sound changes -os > -us and -ōm > -om > -um affect the nominative and accusative singular, and the genitive plural.

- One very early text, the Lapis Satricanus, has genitive -osio (an ending found in several other archaic languages descended from Proto-Indo-European [PIE], languages such as Vedic Sanskrit, Old Persian, and Homeric Greek) rather than -ī[27] (an ending appearing only in Italo-Celtic).. This form also appears in the closely related Faliscan language.

- In the genitive plural, -um (from PIE *-ōm) survived in classical Latin "words for coins and measures";[28] otherwise it was eventually replaced by -ōrum by analogy with 1st declension -ārum.

- The nominative/vocative plural masculine -ei comes from the PIE pronominal ending *-oi. The original ending -oi appears in a late spelling in the word poploe (i.e. "poploi" = populī "people") in Sextus Pompeius Festus.[29]

- The dative/ablative/locative plural -eis comes from earlier -ois, a merger of PIE instrumental plural *-ōis and locative plural *-oisu. The form -ois appears in Sextus Pompeius Festus and a few early inscriptions.

- The Praeneste Fibula has dative singular Numasioi, representing PIE *-ōi.

- A number of "provincial texts" have nominative plural -eis (later -īs from 190 BC on[30]), with an added s, by some sort of analogy with other declensions. Sihler (1995)[29] notes that this form appears in literature only in pronouns and suggests that inscriptional examples added to nouns may be artificial (i.e. not reflecting actual pronunciation).

- In the vocative singular, some nouns lose the -e (i.e. have a zero ending) but not necessarily the same as in classical Latin.[31] The -e alternates regularly with -us.[32]

Third declension (consonant/i)

| rēx, rēges king m. |

ignis -is fire m. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | rēx | rēgeīs, rēgīs, rēgēs, rēgĕs |

ignis, ignes | igneīs, ignēs, ignīs, ignĕs |

| Vocative | ||||

| Accusative | rēgem | rēgeīs, rēgīs, rēgēs |

ignim | igneīs, ignēs, ignīs |

| Genitive | rēges, rēgis, rēgos, rēgus | rēgom, rēgum, rēgerum |

ignis | igniom, ignium |

| Dative | rēgei, rēgī, rēgē, rēgĕ | rēgebus, rēgebūs, rēgibos, rēgibus |

igni, igneī, ignē | ignebus, ignebūs, ignibos, ignibus |

| Ablative | rēgīd, rēgĭd, rēgī, rēgē, rēgĕ |

ignīd, ignĭd, ignī, ignē, ignĕ | ||

| Locative | rēgī | rēgebos | ignī | ignibos |

| Instrumental | rēge | igne | ||

This declension contains nouns that are masculine, feminine, and neuter. The stem ends in the root consonant, except in the special case where it ends in -i (i-stem declension). The i-stem, which is a vowel-stem, partly fused with the consonant-stem in the pre-Latin period and went further in Old Latin.[33] I/y and u/w can be treated as either consonants or vowels; hence they are semi-vowels. Mixed-stem declensions are partly like consonant-stem and partly like i-stem. Consonant-stem declensions vary slightly depending on which consonant is root-final: stop-, r-, n-, s-, etc.[34] The paradigms below include a stop-stem (reg-) and an i-stem (igni-).

For a consonant declension, in the nominative singular, the -s was affixed directly to the stem consonant, but the combination of the two consonants produced modified nominatives over the Old Latin period. The case appears in different stages of modification in different words diachronically.[35] The Latin neuter form (not shown) is the Indo-European nominative without stem ending; for example, cor < *cord "heart."[36]

The genitive singular endings include -is < -es and -us < *-os.[37] In the genitive plural, some forms appear to affix the case ending to the genitive singular rather than the stem: regerum < *reg-is-um.[38]

In the dative singular, -ī succeeded -eī and -ē after 200 BC.

In the accusative singular, -em < *-ṃ after a consonant.[37]

In the ablative singular, the -d was lost after 200 BC.[39] In the dative and ablative plural, the early poets sometimes used -būs.[37]

In the locative singular, the earliest form is like the dative but over the period assimilated to the ablative.[40]

In the instrumental singular, the earliest form is an -e during its early days.

Fourth declension (u)

The stems of the nouns of the u-declension end in ŭ and are masculine, feminine and neuter. In addition there is a ū-stem declension, which contains only a few "isolated" words, such as sūs, "pig", and is not presented here.[41]

| senātus, –uos senate m. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | senātus | senātūs |

| Vocative | ||

| Accusative | senātum | |

| Genitive | senātuos, senātuis, senātī, senātous, senātūs | senātuom, senātum |

| Dative | senātuī | senātubus, senātibus |

| Ablative | senātūd, senātud | |

| Locative | senāti | |

Fifth declension (e)

The 'e-stem' declension's morphology matches the Classical language very nearly.

| rēs, reis thing f. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | rēs, reis | rēs |

| Vocative | rēs | |

| Accusative | rem | |

| Genitive | rēis, rēs | rēsom |

| Dative | reī | rēbos |

| Ablative | rēd | |

| Locative | ||

| Instrumental | rē | |

Personal pronouns

Personal pronouns are among the most common thing found in Old Latin inscriptions. In all three persons, the ablative singular ending is identical to the accusative singular.

| ego, I | tu, you | suī, himself, herself (etc.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| Nominative | ego | tu | — |

| Accusative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| Genitive | mis | tis | sei |

| Dative | mihei, mehei | tibei | sibei |

| Ablative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| Plural | |||

| Nominative | nōs | vōs | — |

| Accusative | sēd | ||

| Genitive | nostrōm, -ōrum, -i |

vostrōm, -ōrum, -i |

sei |

| Dative | nōbeis, nis | vōbeis | sibei |

| Ablative | sēd | ||

Relative pronoun

In Old Latin, the relative pronoun is also another common concept, especially in inscriptions. The forms are quite inconsistent and leave much to be reconstructed by scholars.

| queī, quaī, quod who, what | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

| Nominative | queī | quaī | quod |

| Accusative | quem | quam | |

| Genitive | quoius, quoios, -a, -um/om (according to gender of whatever is owned) | ||

| Dative | quoī, queī, quoieī, queī | ||

| Ablative | quī, quōd | quād | quōd |

| Plural | |||

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

| Nominative | ques, queis | quaī | qua |

| Accusative | quōs | quās | |

| Genitive | quōm, quōrom | quōm, quārom | quōm, quōrom |

| Dative | queis, quīs | ||

| Ablative | |||

Old present and perfects

There is little evidence of the inflection of Old Latin verb forms and the few surviving inscriptions hold many inconsistencies between forms. Therefore, the forms below are ones that are both proved by scholars through Old Latin inscriptions, and recreated by scholars based on other early Indo-European languages such as Greek and Italic dialects such as Oscan and Umbrian, and which also may be compared to modern Spanish.

| Indicative Present: Sum | Indicative Present: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| First Person | (e)som | somos, sumos | sum | sumus | fac(e/ī)ō | fac(e)imos | faciō | facimus |

| Second Person | es | esteīs | es | estis | fac(e/ī)s | fac(e/ī)teis | facis | facitis |

| Third Person | est | sont | est | sunt | fac(e/ī)d/-(e/i)t | fac(e/ī)ont | facit | faciunt |

| Indicative Perfect: Sum | Indicative Perfect: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| First Person | fuei | fuemos | fuī | fuimus | (fe)fecei | (fe)fecemos | fēcī | fēcimus |

| Second Person | fuistei | fuisteīs | fuistī | fuistis | (fe)fecistei | (fe)fecisteis | fēcistī | fēcistis |

| Third Person | fued/fuit | fueront/-erom | fuit | fuērunt/-ēre | (fe)feced/-et | (fe)feceront/-erom | fēcit | fēcērunt/-ēre |

In popular fiction

The Italian director Matteo Rovere has shot the 2019 film The First King: Birth of an Empire and the 2020–2022 TV series Romulus with dialog in a reconstructed version of Old Latin. The linguists have had to make concessions for ease of filming and not going too much against the expectations of viewers. For example, the character of the Lady of the Wolves is Lukwòsom Pòtnia (an allusion to Homer's Potnia theron) since Latin domina did not have the desired nuances. Before rhotacism, Old Latin had lots of sibilants, so some had to be substituted to ease the actors' work.[42]

See also

References

- "Archaic Latin". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition.

- Maras, Daniele F. (Winter 2012). "Scientists declare the Fibula Praenestina and its inscription to be genuine 'beyond any reasonable doubt'" (PDF). Etruscan News. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2012.

- Maras, Daniele Federico. "Scientists declare the Fibula Prenestina and its inscription to be genuine 'beyond any reasonable doubt'". academia.edu. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- De Oratoribus, I.193.

- Book IX.1.6.

- Wordsworth 1874, p. v.

- Histories III.22.

- Bell, Andreas (1889). De Locativi in prisca latinitate vi et usu, dissertatio inauguralis philologica. Breslau: typis Grassi, Barthi et soc (W. Friedrich).

- Bennett 1910, p. iii.

- Weiss, M. (2020). Outline of the Historical and Comparative Grammar of Latin, 2nd ed. Beech Stave: Ann Arbor. Pp. 24.

- Halsey, William D. (1965). Collier's encyclopedia, with Bibliography and Index. USA: The Crowell-Collier Publishing Company. p. 595.

- Allen 1897, p. 8: "There were no such names as Caius, Cnaius"

- Allen 1897, p. 6.

- Bennett 1895, p. 12.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2005) [1904]. A Grammar Of Oscan And Umbrian: With A Collection Of Inscriptions And A Glossary. Languages of classical antiquity, vol. 5. Bristol, Pa.: Evolution Publishing. p. 204.

- Buck 1933, pp. 174–175.

- Wordsworth 1874, p. 45.

- Buck 1933, p. 177.

- Buck 1933, pp. 175–176.

- Wordsworth 1874, p. 48.

- Buck 1933, p. 176.

- Buck 1933, p. 172.

- Palmer 1988, p. 242.

- Buck 1933, p. 173.

- Buck 1933, pp. 99–100.

- Lindsay (1894), p. 383.

- Weiss, M. (2020). Outline of the Historical and Comparative Grammar of Latin, 2nd ed. Beech Stave: Ann Arbor.

- Buck 1933, p. 182.

- Sihler (1995), A New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin.

- Wordsworth 1874, p. 56.

- Buck 1933, p. 181.

- Grandgent, Charles Hall (1908) [1907]. An introduction to vulgar Latin. Heath's modern language series. Boston: D.C. Heath & Co. p. 89.

- Buck 1933, p. 197.

- Buck 1933, pp. 185–193.

- Wordsworth 1874, pp. 67–73.

- Buck 1933, p. 185.

- Bennett 1895, p. 117.

- Roby 1872, p. 162.

- Allen 1897, p. 9.

- Gildersleeve & Lodge 1900, p. 18.

- Buck 1933, pp. 198–201.

- Gargantini, Gabriele (20 November 2020). "Seike Romulos deiksed". Il Post (in Italian). Retrieved 19 October 2022.

Bibliography

- Allen, Frederic de Forest (1897). Remnants of Early Latin. Ginn.

- Bennett, Charles Edwin (1895). A Latin Grammar: With Appendix for Teachers and Advanced Students. Boston, Chicago: Allyn and Bacon.

- Bennett, Charles Edwin (1907). The Latin Language: A Historical Outline of Its Sounds, Inflections, and Syntax. Allyn and Bacon.

- Bennett, Charles Edwin (1910). Syntax of Early Latin. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Buck, Carl Darling (1933). Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Gildersleeve, Basil Lanneau; Lodge, Gonzalez (1900). Gildersleeve's Latin grammar (3rd ed.). New York, Boston, New Orleans, London: University Publishing Company.

- Lindsay, Wallace Martin (1894). The Latin language: an historical account of Latin sounds, stems and flexions. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Palmer, Leonard Robert (1988) [1954]. The Latin language. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Roby, Henry John (1872). A grammar of the Latin language from Plautus to Suetonius. Vol. I (2nd ed.). London: MacMillan and Co.

- Wordsworth, John (1874). Fragments and specimens of early Latin, with Introduction and Notes. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Further reading

- Goldberg, Sander M. 2007. "Antiquity's antiquity." In Latinitas Perennis. Vol. 1, The continuity of Latin literature. Edited by Wim Verbaal, Yanick Maes, and Jan Papy, 17–29. Brill's Studies in Intellectual History 144. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Lembke, Janet. 1973. Bronze and Iron: Old Latin Poetry From Its Beginnings to 100 B.C. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mercado, Angelo. 2012. Italic Verse: A Study of the Poetic Remains of Old Latin, Faliscan, and Sabellic. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen der Universität Innsbruck.

- Vine, Brent. 1993. Studies in Archaic Latin inscriptions. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 75. Innsbruck, Austria: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Univ. Innsbruck.

- Warmington, E. H. 1979. Remains of Old Latin. Rev. ed. 4 vols. Loeb Classical Library 294, 314, 329, 359. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press.

- Warner, R. 1980. "Word Order in Old Latin: Copulative Clauses." Orbis 29, no.1: 251–63.

External links

| Library resources about Old Latin |

- Gippert, Jost (1994–2001). "Old Latin Inscriptions" (in German and English). Titus Didactica. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- glottothèque – Ancient Indo-European Grammars online, an online collection of introductory videos to Ancient Indo-European languages produced by the University of Göttingen