Early New High German

Early New High German (ENHG) is a term for the period in the history of the German language generally defined, following Wilhelm Scherer,[1] as the period 1350 to 1650.[2]

| Early New High German | |

|---|---|

| Deutsch | |

| Region | Germany, parts of Austria and Switzerland |

| Era | Late Middle Ages, Early modern period |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

The term is the standard translation of the German Frühneuhochdeutsch (Frnhd., Fnhd.), introduced by Scherer. The term Early Modern High German is also occasionally used for this period (but the abbreviation EMHG is generally used for Early Middle High German).

Periodisation

The start and end dates of ENHG are, like all linguistic periodisations, somewhat arbitrary. In spite of many alternative suggestions, Scherer's dates still command widespread acceptance.[3] Linguistically, the mid-14th century is marked by the phonological changes to the vowel system that characterise the modern standard language; the mid-17th sees the loss of status for regional forms of language, and the triumph of German over Latin as the dominant, and then sole, language for public discourse.

Scherer's dates also have the merit of coinciding with two major demographic catastrophes with linguistic consequences: the Black Death, and the end of the Thirty Years' War. Arguably, the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, by ending religious wars and creating a Germany of many small sovereign states, brought about the essential political conditions for the final development of a universally acceptable standard language in the subsequent New High German period.

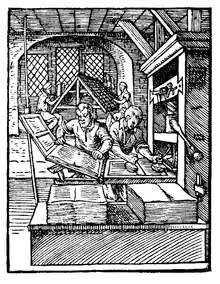

Alternative periodisations take the period to begin later, such as the invention of printing with moveable type in the 1450s.[4]

Geographical variation

There was no standard Early New High German, and all forms of language display some local or regional characteristics. However, there was increasing harmonisation in the written and printed word, the start of developments towards the unified standard which was codified in the New High German period.

Dialects

With the end of eastward expansion, the geographical spread and the dialect map of German in the ENHG period remained the same as at the close of the MHG period.[5]

| ENHG Dialects[5][6] | West | East |

|---|---|---|

| Central German |

Bohemian | |

| Upper German |

North Bavarian Middle Bavarian South Bavarian |

Druckersprachen, "printers' languages"

Since the printers had a commercial interest in making their texts acceptable to a wide readership, they often strove to avoid purely local forms of language.[7] This gave rise to so-called Druckersprachen ("printers' languages"), which are not necessarily identical to the spoken dialect of the town where the press was located.[5] The most important centres of printing, with their regional Druckersprachen are:

- West Central German: Frankfurt, Mainz, Worms, Cologne

- East Central German: Wittenberg, Erfurt, Leipzig

- Swabian: Augsburg, Ulm, Tübingen

- Alemannic: Basel, Strassburg, Zürich

- East Franconian: Nuremberg, Bamberg, Würzburg

- Austro-Bavarian: Ingolstadt, Vienna.[8]

Chancery languages

While the language of the printers remained regional, the period saw the gradual development of two forms of German (one Upper German, one Central German), which were supra-regional: the Schriftsprachen ("written languages", "documentary languages") of the chanceries of the two main political centres.[9]

- The gemaine tiutsch ("common German") of the Chancery of the Emperor Maximilian I and his successors in Prague and then Vienna.

- The East Central German of the Chancery of the Electorate of Saxony in Meissen

The language of these centres had influence well beyond their own territorial and dialect boundaries.

Emperor Maximilian's chancery was the first concerted and successful effort to introduce a standardised form of German for all German chanceries, and hence avoided the most idiosyncratic features of Austrian Upper German standards in favour of Central German alternatives. Emperor Maximilian's Prague Chancery and the Saxon Chancery used similar standards of German as they were bordering each other, both dialects originating from the linguistic admixture in the course of eastward German settlement. In addition, many Bohemians had fled to Saxony during the Hussite Wars, reinforcing the similarities between the dialects.[10]

The influence of the Saxon Chancery was due in part to its adoption for his own published works by Martin Luther, who stated, "Ich rede nach der sächsischen Canzley, welcher nachfolgen alle Fürsten und Könige in Deutschland" ("My language is based on that of the Saxon Chancery, which is followed by all the princes and kings in Germany").[11]

He also recognized the standardising force of the two chanceries: "Kaiser Maximilian und Kurf. Friedrich, H. zu Sachsen etc. haben im römischen Reich die deutschen Sprachen also in eine gewisse Sprache gezogen" ("The Emperor Maximilian and Duke Frederick, Elector of Saxony etc., have drawn the languages of Germany together").[11]

Low German

Middle Low German, spoken across the whole of Northern Germany north of the Benrath Line in the Middle Ages, was a distinct West Germanic language. From the start of the 16th century, however, High German came increasingly to be used in this area not only in writing but also in the pulpit and in schools. By the end of the ENHG period, Low German had almost completely ceased to be used in writing or in formal and public speech and had become the low-status variant in a diglossic situation, with High German as the high-status variant.[12]

Phonology and orthography

For a number of reasons it is not possible to give a single phonological system for ENHG:

- dialectal variation

- the differing times at which individual dialects introduced even shared sound changes

- the lack of a prestige variant (such as the "Dichtersprache" provides for Middle High German)

Also, the difficulty of deriving phonological information from the complexity of ENHG orthography means that many reference works do not treat orthography and phonology separately for this period.[13]

Vowels

The MHG vowel system undergoes significant changes in the transition to ENHG and their uneven geographical distribution has served to further differentiate the modern dialects.

Diphthongization

The long high vowels /iː/, /uː/ and /yː/ (spelt ⟨î⟩, ⟨û⟩ and ⟨iu⟩) are diphthongized to /aɪ/, /aʊ/ and /ɔʏ/, spelt ⟨ei⟩, ⟨au⟩ and ⟨eu/äu⟩. In many dialects they fall together with the original MHG diphthongs ⟨ei⟩, ⟨ou⟩ and ⟨öu⟩ /øy/, which are all lowered.

Examples:

- MHG snîden ("to cut") > NHG schneiden

- MHG hût ("skin") > NHG Haut

- MHG liute ("people") > NHG Leute.

This change started as early as the 12th century in Upper Bavarian, and only reached Moselle Franconian in the 16th century. It does not affect Alemannic (apart from Swabian) or Ripuarian dialects, which still retain the original long vowels. The map shows the distribution and chronology of this sound change.[14] In Bavarian, the original diphthongs are monophthongized, avoiding a merger with the new diphthongs.

Monophthongisation

The MHG falling diphthongs /iə/, /uə/ and /yə/ (spelt ⟨ie⟩, ⟨uo⟩ and ⟨üe⟩) are monophthongised, replacing the long high vowels lost in the diphthongisation. In the case of /iə/ > /iː/ the MHG spelling is retained and in Modern German ⟨ie⟩ indicates the long vowel.

Examples:

- MHG liebe ("love) > NHG Liebe /liːbə/

- MHG bruoder ("brother") > NHG Bruder /bruːdər/

- MHG brüeder ("brothers") > NHG Brüder /bryːdər/

This change, sometimes called the Central German Monophthongisation, affects mainly the Central German dialects, along with South Franconian and East Franconian. The other Upper German dialects largely retain the original diphthongs.[15][16]

Changes in vowel quantity

There are two changes in vowel quantity in ENHG, the lengthening of short vowels and the shortening of long vowels. Both show wide variation between dialects but appear earlier and more completely in Central German dialects. Many individual words form exceptions to these changes, though the lengthening is carried out more consistently.[17][18][19]

1. Lengthening: MHG short vowels in open syllables (that is, syllables that end in a vowel) tend to be lengthened in the ENHG period. This is not reflected directly in spelling, but it is the source of the Modern German spelling convention that a vowel ending a syllable is always long.[20]

Examples:

- MHG sagen /zaɡən/ ("to say") > NHG sagen /zaːɡən/

- MHG übel /ybəl/ ("evil") > NHG Übel /yːbəl/

2. Shortening: MHG long vowels tend to be shortened in the ENHG period before certain consonants (m, t and others) and before certain consonant combinations (/xt/, /ft/, and /m/, /n/, /l/, /r/ followed by another consonant).[21]

Examples:

- MHG hât ("has") > NHG hat

- MHG dâhte ("thought") > NHG dachte

- MHG lêrche ("lark") > NHG Lerche

- MHG jâmer ("suffering") > NHG Jammer

This shortening seems to have taken place later than the monophthongisation, since the long vowels which result from that change are often shortened.

Examples:

- MHG muoter ("mother" > NHG Mutter (via /muːtər/)

- MHG lieht ("light" > NHG Licht (via /liːxt/)

Consonants

The overall consonant system of German remains largely unchanged in the transition from MHG to Modern German. However, in many cases sounds changed in particular environments and therefore changed in distribution.[16] Some of the more significant are the following. (In addition, there are many other changes in particular dialects or in particular words.)

/s/

- MHG had two sibilants, written ⟨s⟩/⟨ss⟩ and ⟨z⟩/⟨zz⟩. The difference between these is uncertain, but in ENHG both fell together in /s/. (The affricate /t͡s/, for which ⟨z⟩ is also used, remained unchanged.)

- Before vowels this /s/ becomes voiced to /z/, e.g. MHG sehen /sehən/ ("to see") > NHG sehen /zeːən/.

- Initially before consonants /s/ becomes /ʃ/, indicated by the grapheme <sch>, e.g. MHG snîden ("to cut") > NHG schneiden . Before /p/ and /t/ this is not indicated in spelling, e.g. MHG stein ("stone") > NHG Stein /ʃtain/.[22]

/w/

- In initial position the bilabial fricative /w/ becomes the labio-dental /v/, though this is not reflected in any change in spelling, e.g. MHG wil ("want to") > NHG will /vil/. In a few words, this also takes place between vowels, e.g. ewig /eːviɡ/ ("eternal").

- Otherwise it is either lost, e.g. MHG snėwes ("of the snow") > NHG Schnees, or forms a diphthong with a neighbouring vowel (e.g. MHG brâwe ("brow") > NHG Braue.[23]

/h/

- Medial /h/ is lost, though it remains in spelling to indicate the length of the preceding vowel, e.g. MHG sehen /sehən/ ("to see") > NHG sehen /zeːən/.[24]

The loss of /w/ and the ⟨s⟩:⟨z⟩ contrast are the only structural changes to the consonant system.

Morphology

As with phonology, the range of variation between dialects and time periods makes it impossible to cite a unified morphology for ENHG. The sound changes of the vowels had which brought consequent changes to

- verb conjugations

- further simplification of the noun declensions

Syntax

The following are the main syntactical developments in ENHG:[25][26][27]

- Noun phrase

- Increasing complexity: in chancery documents noun phrases increasingly incorporate prepositional and participial phases, and this development spreads from there to other types of formal and official writing.

- Attributive genitive: the so-called "Saxon genitive", in which the genitive phrase precedes the noun (e.g. der sunnen schein, literally "of-the-sun shine") increasingly makes way for the now standard, post-nominal construction (e.g. der schein der sonne, literally "the shine of the sun"), though it remains the norm where the noun in the genitive is a proper noun (Marias Auto).

- Verb phrase

- Increasing complexity: more complex verbal constructions with participles and infinitives.

- Verb position: the positioning of verbal components characteristic of NHG (finite verb second in main clauses, first in subordinate clauses; non-finite verb forms in clause-final position) gradually becomes firmly established.

- Decline of the preterite: an earlier development in the spoken language (especially in Upper German), the replacement of simple preterite forms by perfect forms with an auxiliary verb and the past participle becomes increasingly common from the 17th century.

- Negation: double negation ceases to be acceptable as an intensified negation; the enclitic negative particle ne/en falls out of use and an adverb of negation (nicht, nie) becomes obligatory (e.g.MHG ine weiz (niht), ENHG ich weiss nicht, "I don't know").

- Case government

- Decline of the genitive: Verbs that take a genitive object increasingly replace this with an accusative object or a prepositional phrase. Prepositions that govern the genitive likewise tend to switch to the accusative.

Literature

The period saw the invention of printing with moveable type (c.1455) and the Reformation (from 1517). Both of these were significant contributors to the development of the Modern German Standard language, as they further promoted the development of non-local forms of language and exposed all speakers to forms of German from outside their own area – even the illiterate, who were read to. The most important single text of the period was Luther's Bible translation, the first part of which was published in 1522, though this is now not credited with the central role in creating the standard that was once attributed to it. This is also the first period in which prose works, both literary and discursive, became more numerous and more important than verse.

Example texts

The Gospel of John, 1:1–5

| Luther, 1545[28] | Luther Bible, 2017[29] | King James Version | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Im anfang war das Wort / Vnd das Wort war bey Gott / vnd Gott war das Wort. | Im Anfang war das Wort, und das Wort war bei Gott, und Gott war das Wort. | In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. |

| 2 | Das selbige war im anfang bey Gott. | Dasselbe war im Anfang bei Gott. | The same was in the beginning with God. |

| 3 | Alle ding sind durch dasselbige gemacht / vnd on dasselbige ist nichts gemacht / was gemacht ist. | Alle Dinge sind durch dasselbe gemacht, und ohne dasselbe ist nichts gemacht, was gemacht ist. | All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. |

| 4 | Jn jm war das Leben / vnd das Leben war das Liecht der Menschen / | In ihm war das Leben, und das Leben war das Licht der Menschen. | In him was life; and the life was the light of men. |

| 5 | vnd das Liecht scheinet in der Finsternis / vnd die Finsternis habens nicht begriffen. | Und das Licht scheint in der Finsternis, und die Finsternis hat's nicht ergriffen. | And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not. |

| 6 | ES ward ein Mensch von Gott gesand / der hies Johannes. | Es war ein Mensch, von Gott gesandt, der hieß Johannes. | There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. |

| 7 | Derselbige kam zum zeugnis / das er von dem Liecht zeugete / auff das sie alle durch jn gleubten. | Der kam zum Zeugnis, damit er von dem Licht zeuge, auf dass alle durch ihn glaubten. | The same came for a witness, to bear witness of the Light, that all men through him might believe. |

| 8 | Er war nicht das Liecht / sondern das er zeugete von dem Liecht. | Er war nicht das Licht, sondern er sollte zeugen von dem Licht. | He was not that Light, but was sent to bear witness of that Light. |

| 9 | Das war das warhafftige Liecht / welchs alle Menschen erleuchtet / die in diese Welt komen. | Das war das wahre Licht, das alle Menschen erleuchtet, die in diese Welt kommen. | That was the true Light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world. |

From Fortunatus

| Original[30] | English translation[31] |

|---|---|

| Ain land, genanntt Cipern, Ist ain inßel vnd künigreich gegen der sonnen auffgang im mör gelegen, fast wunsam, lustig vnd fruchtbar aller handen edler natürlicher früchten, manigem wissend, der tzu dem hailigen land Jerusalem gefarn vnd im selben künigreich Cipern zugelendt vnd da gewesen ist. | The Kingdom of Cyprus is an island situated close to where the sun rises from the sea: a delightful, merry, fertile island, full of all kinds of fruits, and known to many who have landed and passed some time there on their journey to Jerusalem, in the Holy Land. |

| Darinn ain treffenliche statt, genannt Famagosta, in wölicher stat ain edler purger altz herkommens was geseßsen. | It contains a splendid city, Famagusta, which was once the seat of a noble burgher of ancient lineage. |

| Dem sein öltern groß hab vnnd gut verlassen hetten, allso, das er fast reich, mächtig vnnd darbey iung was, aines freyen muttes. | His parents had left him much money and property, so that he was very rich and powerful; but he was also very young and of a careless disposition. |

| Wenig betrachtet, wie seine elteren zu tzeiten das ir erspart vnd gemeert hettend, vnnd sein gemüt was gentzlichen gericht auff zeitlich eer, freüd vnd wollust des leibs. | He had taken but little notice of how his parents had saved and increased their money, and his mind was wholly preoccupied with the pursuit of honour and physical pleasures. |

| Vnd nam an sich ainen kostlichen stand mitt stechenn, turnieren, dem künig gen hoff tzureytten vnnd ander sachenn, Darmitt er groß gut on ward vnnd seine freünd wol kunden mercken, das er mer on ward, dann sein nutzung ertragen mocht, vnd gedachtend jm ain weib zu geben, ob sy jn von sollichem ziehen möchten, vnd legten ym das für. | So he maintained himself in great state, jousting, tourneying, and travelling around with the King's Court, and losing much money thereby. His friends, soon noticing that he was in danger of losing more than his means could bear, thought of giving him a wife, in the hope that she would curb his expenditure. When they suggested this to him, he was highly pleased, and he promised to follow their advice; and so they began to search for a suitable spouse. |

See also

Notes

- Scherer 1878, p. 13.

- Wells 1987, p. 23. "1350–1650... seems the most widely accepted dating."

- Roelcke 1998. lists the various suggestions.

- Wells 1987, p. 25.

- Schmidt 2013, p. 349.

- Piirainen 1985, p. 1371.

- Bach 1965, p. 254.

- Schmidt 2013, p. 350.

- Keller 1978, pp. 365–368.

- Waterman, John T. (1991). A History of the German Language Revised Edition. Waveland Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 9781478648734.

- Luther 1566, 1040.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, p. 34.

- Ebert et al. 1993, pp. 13–17, , has detailed discussion of the issues.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, pp. 134–136.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, pp. 136.

- Wolf 1985, p. 1310.

- von Kienle 1969, p. 37.

- Waterman 1966, p. 103.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, p. 137.

- von Kienle 1969, pp. 37–40.

- von Kienle 1969, pp. 40–42.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, pp. 145–6.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, pp. 146–7.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, pp. 147.

- Hartweg & Wegera 2005, pp. 173–178.

- Wells 1987, pp. 227–262.

- Keller 1978, pp. 434–442.

- Luther 1545. Printed in Wittenberg 1545; dialect East Central German

- Luther 2017.

- Anonymous 1509. Printed in Augsburg; dialect Swabian

- Haldane 2005.

References

- Bach, Adolf (1965). Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (8 ed.). Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer.

- Besch W (1980). "Frühneuhochdeutsch". In Althaus HP, Henne H, Wiegand HE (eds.). Lexikon der Germanistischen Linguistik (in German). Vol. III (2 ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 588–597. ISBN 3-484-10391-4.

- Brooke, Kenneth (1955). An Introduction to Early New High German. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Ebert, Peter; Reichmann, Oskar; Solms, Hans-Joachim; Wegera, Klaus-Peter (1993). Frühneuhochdeutsche Grammatik. Sammlung kurzer Grammatiken germanischer Dialekte, A.12. Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-10672-7.

- Hartweg, Frédéric; Wegera, Klaus-Peter (2005). Frühneuhochdeutsch. Germanistische Arbeitsheft 33 (2 ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-25133-6.

- Keller, R. E. (1978). The German Language. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-11159-9.

- Piirainen IT (1985). "Die Diagliederung des Frühneuhochdeutschen". In Besch W, Reichmann O, Sonderegger S (eds.). Sprachgeschichte. Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und ihrer Erforschung (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 1369–1378. ISBN 3-11-009590-4.

- Roelcke T (1998). "Die Periodisierung der deutschen Sprachgeschichte". In Besch W, Betten A, Reichmann O, Sonderegger S (eds.). Sprachgeschichte. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 798–815. ISBN 3-11-011257-4.

- Scherer (1878). Zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (2nd ed.). Berlin: Weidmann.

- Schmidt, Wilhelm (2013). Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (11 ed.). Stuttgart: Hirzel. ISBN 978-3-7776-2272-9.

- von Kienle, Richard (1969). Historische Laut- und Formenlehre des Deutschen (2 ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Waterman, John. T. (1966). A History of the German Language. Seattle, London: University of Washington. ISBN 0-295-73807-3.

- Wells, C. J. (1987). German: A Linguistic History to 1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815809-2.

- Wolf NR (1985). "Phonetik und Phonologie, Graphetik und Graphemik des Frühneuhochdeutschen". In Besch W, Reichmann O, Sonderegger S (eds.). Sprachgeschichte. Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und ihrer Erforschung (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 1305–1313. ISBN 3-11-009590-4.

Primary Sources

- "Fortunatus. The first complete translation into English of the editio princeps". Translated by Haldane, Michael. 2005. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Anonymous (1509). "Fortunatus". Henricus – Edition Deutsche Klassik UG. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Luther, Martin (1545). "Johannes – Kapitel 1". Bibel-Online.NET. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Luther, Martin (1566). Tischreden.

- Luther, Martin (2017). "Das Evangelium nach Johannes". Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

Further reading

Grammar

- Moser, Hugo; Stopp, Hugo (1970–1988). Grammatik des Frühneuhochdeutschen. Beiträge zur Laut- und Formenlehre. Heidelberg: Winter. 7 vols.

- Moser, Virgil (1971). Historisch-grammatische Einführung in die frühneuhochdeutschen Schriftdialekte. Darmstadt: Wissenschafliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3487532837. (Reprint of 1909 edition)

Dictionaries

- Alfred Götze. Frühneuhochdeutsches Glossar. 2. Aufl. Bonn 1920 (= Kleine Texte für Vorlesungen und Übungen, 101); 5. Aufl. Berlin 1956; Neudrucke 1960 u. ö. The second edition (1920) is online: archive.org.

- Christa Baufeld, Kleines frühneuhochdeutsches Wörterbuch. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-484-10268-3.

- Frühneuhochdeutsches Wörterbuch. Hrsg. von Robert R. Anderson [für Bd. 1] / Ulrich Goebel / Anja Lobenstein-Reichmann [für die Bände 5, 6, 11–13] und Oskar Reichmann. Berlin / New York 1989 ff.

External links

- Early New High German texts (German Wikisource)

- Luther's translation of the New Testament (German Wikisource)