Edict of Paris

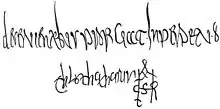

The Edict of Paris was promulgated 18 October 614 (or perhaps 615) in Paris by Chlothar II, the Merovingian king of the Franks. It is one of the most important royal instruments of the Merovingian period in Frankish history and a hallmark in the history of the development of the Frankish monarchy. It is the last of the Merovingian capitularia, a series of legal ordinances governing church and realm.

The Edict was issued shortly after the Synod of Paris and draws on canons 1–4, 6–7, 10 and 18 of that synod. Chlothar had recently assumed the full kingship of the Franks, in 613, when he deposed his cousin Sigebert II, king of Austrasia, and his regent, his great-grandmother Brunhilda. The Edict has been commonly seen as a series of concessions to the Austrasian nobility, which had sided with him against Brunhilda. In Der Staat des hohen Mittelalters, Heinrich Mitteis compared the Edict to the English Magna Carta. More popular now is the belief that it was primarily aimed at correcting abuses which had entered the judicial system during the civil wars which had dominated the kingdom since the beginning of the feud of Brunhilda with Chlothar's mother, Fredegund (568). It cannot be known how much of the Edict's language and ideas stem from the king and his officers and courtiers and how much from the nobles. Some of its clauses were designed to amend decisions of the prelates at the synod that had just finished sitting. The bishops insisted upon freedom in the choice of bishops, but Chlothar modified the council's decisions by insisting that only the bishops he wanted, or those sent from amongst suitable priests at court, should be consecrated.

The Edict throughout attempts to establish order by standardising orderly appointments to offices, both ecclesiastic and secular, and by asserting the responsibilities of all—the magnates, bishops, and the king—to secure the happiness and peace of the realm: the felicitas regni and pax et disciplina in regno. Among the true concessions granted by the Edict were the ban on Jews in royal offices,[lower-alpha 1] leaving all such appointments to the Frankish nobility, the granting of the right to bishops of deposing poor judges (if the king was unable at the time), and certain tax cuts and exemptions. Despite the exclusion of Jews from high office, their right to bring legal actions against Christians was preserved. Similarly, the right of a woman not to be married against her will was affirmed.

The most famous of the twenty seven clauses of the Edict is almost certainly number twelve, in which Chlothar says in part that nullus iudex de aliis provinciis aut regionibus in alia loca ordinetur, meaning that judges should be appointed only within their own regions. It has been interpreted as a concession, granting the magnates more control over appointments and the king less ability to influence, and conversely as a piece of anti-corruption legislation, intended to ease the penalisation of corrupt officers.

The Edict of Paris remained in force during the reign of his successor, Dagobert.

Notes

- The Synod had enacted that all Jews holding military or civil positions must accept baptism, together with their families.

Sources

- Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. (1962) The Long-haired Kings. London.

- Wilson, Emily. "The Rise of the Carolingians or the Decline of the Merovingians?" Access History, 2(1), 5–21.

- Murray, Alexander Callander (1994). "Immunity, Nobility, and the Edict of Paris," Speculum, 69(1), 18–39. doi:10.2307/2864783