Chlothar II

Chlothar II,[lower-alpha 1] sometime called "the Young" (French: le Jeune), (May/June 584 – 18 October 629)[2] was king of the Franks, ruling Neustria (584-629), Burgundy (613-629) and Austrasia (613-623).

| Chlothar II | |

|---|---|

| King of the Franks | |

Coin of Chlothar II | |

| King of Neustria/Soissons | |

| Reign | 584–629 |

| Predecessor | Chilperic I |

| Successor | Dagobert I (in Neustria) Charibert II in Aquitaine |

| King of Burgundy | |

| Reign | 613–629 |

| Predecessor | Sigibert II |

| Successor | Dagobert I |

| King of Austrasia | |

| Reign | 613–623 |

| Predecessor | Sigibert II |

| Successor | Dagobert I |

| Born | May/June 584[1] |

| Died | late 629 or early 630 (aged 45 or 46) |

| Spouses |

|

| Issue | Charibert II Dagobert I |

| House | Merovingian |

| Father | Chilperic I |

| Mother | Fredegund |

| Signature |  |

The son of Chilperic I and his third wife, Fredegund, he started his reign as an infant under the regency of his mother, who was in an uneasy alliance with Chlothar's uncle King Guntram of Burgundy, who died in 592. Chlothar took power upon the death of his mother in 597; though rich, his realm was one of the smallest portions of Francia. He continued his mother's feud with Queen Brunhilda with equal viciousness and bloodshed, finally achieving her execution in an especially brutal manner in 613, after winning the battle that enabled Chlothar to unite Francia under his rule. Like his father, he built up his territories by seizing lands after the deaths of other kings.

His reign was long by contemporary standards, but saw the continuing erosion of royal power to the French nobility and the church against a backdrop of feuding among the Merovingians. The Edict of Paris in 614, concerned with several aspects of appointments to offices and the administration of the kingdom, has been interpreted in different ways by modern historians. In 617 he made the mayor of the Palace a role held for life, an important step in the progress of this office from being first the manager of the royal household to the effective head of government, and eventually the monarch, under Pepin the Short in 751. Chlothar was forced to cede rule over Austrasia to his young son Dagobert I in 623.

Unusually for a Merovingian monarch, he practised monogamy, though early deaths meant that he had three wives. He was generally an ally of the church and, perhaps inspired by the example of his uncle Guntram, his reign seems to lack outrageous acts of murder, the execution of Brunhilda excepted.

Background

Frankish territories in the sixth century

The domain of Clothar II was located in the territorial and political framework derived from the Frankish kingdom present at 561 at the death of Clothar, son of Clovis and grandfather of Clothar II.

On the death of Clovis in 511, four kingdoms were established with capitals at Reims, Soissons, Paris, and Orléans, Aquitaine being distributed separately. In the year 550, Clothar I, the last survivor of four brothers reunited the Frankish kingdom, and added Burgundian territory (Burgundia) by conquest.

In 561, the four sons of Clothar I followed the events of 511 similarly and split the kingdom again: Sigebert I in Reims, Chilperic I in Soissons, Charibert I in Paris, and Guntram in Orleans, which then included the Burgundian kingdom territory (Burgundia). They divided Aquitaine separately again. Very quickly, Sigebert moved his capital from Reims to Metz, while Guntram moved his from Orléans to Chalon. On the death of Charibert in 567, the land was again split between the three survivors, of greatest importance Sigebert (Metz) received Paris and Chilperic (Soissons) received Rouen. The names Austrasia and Neustria seem to have appeared as the names of these kingdoms for the first time at this point.

Ambitions of Fredegund

In 560, Sigebert and Chilperic married two sisters, daughters of the Visigoth king of Spain Athanagild; princesses Brunhilda, and Galswintha respectively. However Chilperic was still very much attached to his lover and consort, Fredegund, causing Galswintha to wish to return to her homeland in Toledo. In 568 she was murdered and within days, after a brief period of grieving, Chilperic officially married Fredegund and elevated her to a queen of a Frankish kingdom. "After this action his brothers thought that the queen mentioned above had been killed at his command..."[3]

Chilperic agreed, at first, to pay a sum of money to end the feud, but not soon after decided to embark on a series of military operations against Sigebert. This was the beginning of what is called the "royal feud " which did not end until Brunhilda died in 613. The main episodes until the assassination of Chilperic in 584 were as follows: the assassination of Sigebert (575), the imprisonment of Brunhilde and her marriage to a son of Chilperic, and the return of Brunhilda to her son Childebert II, successor of Sigebert.

Moreover, Fredegund strove to ensure her position, since she was from lower origins, by eliminating the sons that Chilperic had with his previous wife Audovera: Merovech and Clovis. Her own children, however, died at a very young age and appeared to be by foul play. When Fredegund had a son in the spring of 584, he would have been the future successor of Chilperic I, if he had lived long enough.

Sources

The main sources from the time are the chronicles of Gregory of Tours and the Chronicle of Fredegar. It is possible, however, that the authors contain a degree of bias in their works; for instance Gregory was a key figure in some of the conflicts of the time. The History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours in the late sixth century only recounts up to 591. It is favorable to Queen Brunhild, Sigebert, and Chilperic but extremely hostile to Fredegund. The Chronicle of Fredegar, beginning in 584, on the other hand is extremely hostile to Brunhild. That chronicle includes:

- The Biography of Clothar II

- Clothar II deals with the Lombards

Early life

Under Frankish customs, newborns did not receive names initially, in order not to spread concern related to the symbolic name of the Merovingian. Wanting to choose a name based on the development of unrest in the kingdom of the Franks, his father did not baptize him immediately.[4] Chilperic and Fredegund desired to protect their child, since their four older sons may have been victims of murder, and there was much political intrigue at the time. He was raised in secret in the royal villa in Vitry-en-Artois to avoid detection.

In September 584, Chilperic I was murdered after a hunt near his villa of Chelles, perhaps on the order of Queen Brunhilda. This event produced general disorder and unrest.[5] In this time Austrasians plundered parts of Neustria, seizing valuable treasures and goods, as well as important documents.[6] Princess Rigunth, on the way to Spain to marry Prince Reccared, was captured by Duke Didier of Toulouse and was linked in conspiracy with Gondovald, who stole all that remained of her dowry, so that she was forced to abandon the marriage.[7] Wars broke out between rival cities, and Orléans, Blois and Chartres stood against Châteaudun.[8]

Fredegund managed to keep most of the treasury of the state as well as key political figures, such as the generals Ansoald and Audon, although many, such as chamberlain Eberul, abandoned her. She took her son to Vitry and sent a message to Guntram, King of Burgundy, asking him to adopt the child and offer his protection to him in return for exercising his authority over Neustria until the boy came of age.[9]

Childebert II, who was at Meaux when Chilperic was murdered, considered an attack on Paris, but Guntram was ahead of him. Childebert II began negotiations with Brunhilda on one hand, Guntram on the other; Guntram, however, refused many of his requests, including allowing him into Paris. He refused to deliver Fredegund, whom Brunhilda claimed was behind the regicide of Sigebert I, Clovis, and even Chilperic I.[6]

Guntram convened a meeting of Greater Neustria, in which the court recognized Clothar as the son of Chilperic, although there were some doubts about his paternal identity. It was at this time that they gave him the name Clothar, naming him after his grandfather. Guntram then took legal responsibility of the child, adopting him and becoming his godfather.[6]

Ansoald was responsible for regaining control of cities Neustria had lost since the death of Chilperic. They then swore allegiance to Guntram and Clothar after their capture. Guntram, attempting to restore order in the affairs of Neustria, likely against the advice of Fredegund and, perhaps, to show his authority, replaced key figures in the episcopal see of the church and moved its location.[10] Bishop Promotus of Châteaudun, whose diocese was demoted after the parish council of Paris in 573, saw this as a violation of canon law; after the death of Sigebert I, he demanded to return from exile, and was thus restored much of his personal property.[6]

Two envoys from Brunhilde, Duke Gararic and chamberlain Eberon, succeeded in swaying Limoges, Tours, and Poitiers towards Austrasian influence, with the help of bishops Gregory of Tours and Venantius Fortunat. Guntram responded by sending troops to recover the lost cities that promptly returned their loyalties to Guntram and Clothar.[6] Fredegund was sent to the Villa de Vaudreuil, in the diocese of Rouen, where she was put under the supervision of the bishop Pretextatus.

During the summer of 585, Guntram returned to Paris to act as godfather of Clothar, as he swore to Fredegund, along with three bishops and three hundred nobles of Neustria who recognized Clothar II as the son of Chilperic I. However, the baptism at this time was postponed. It was expected to reconvene at the council of Troyes, but Austrasia refused to participate if Guntram would not disinherit Clothar. The council was moved to Burgundy and Clothar was baptized on 23 October 585.

While Guntram campaigned to capture Visigothic Septimania, Fredegund escaped custody of the bishop and fled Rouen. During Sunday Mass, Pretextatus was stabbed, although he did not die immediately. Fredegund attempted to fetch doctors and gain his favor. However, he openly accused her of being behind this attack and the murder of the various kings. He publicly cursed and denounced her before dying soon after.[6]

The queen then used her new freedom to rally as many nobles and bishops as could be found to her son. She was reinstalled into power despite Guntram's exile of her.[6] Guntram then attempted to weaken Fredegund's influence by swaying some of the Neustrian aristocracy to his side, and keep Neustrian lands he held between the Loire and Seine by rallying Duke Beppolène. In 587, he managed to capture the towns of Angers, Saintes, and Nantes.[6]

Fredegund then offered to negotiate peace and sent ambassadors to Guntram. But they were arrested and Guntram severed relations with Neustria, approaching Brunhilda and Childebert II, with whom he concluded the pact of Andelot: agreeing that upon the death of one of the two kings, the other would inherit his kingdom. In 592 Guntram died and Childebert became king of Austrasia and Burgundy.[6]

The Austrasia-Burgundy union lasted only until 595, when the death of Childebert II brought it to an end. His realm was then split between his two sons: Theudebert II inherited Austrasia, while Theuderic II received the kingdom of Burgundy. The two brothers then campaigned united against their cousin Chlothar II of Neustria, but their alliance lasted only until 599, when they took up arms against each other.[6]

In 593, although only as a symbolic presence since he was only nine years old, Clothar II appeared at the head of his army, which routed the Austrasian Duke Wintrio who was invading Neustria, in the Battle of Droizy. In 596, Clotaire and Fredegund took Paris, which was supposed to be held in common. Fredegund, then her son's regent, sent a force to Laffaux, and the armies of Theudebert and Theuderic were defeated.[6] Fredegund died in 597, leaving Clothar to rule over Neustria alone, although the boy king didn't do anything significant for 2 more years.

Ruler of Neustria

Battle of Dormelles

In 599, he made war with his nephews, Theuderic II of Burgundy and Theudebert II of Austrasia, who were old enough to be his cousins. They defeated him at Dormelles (near Montereau), forcing him to sign a treaty that reduced his kingdom to the regions of Beauvais, Amiens and Rouen, with the remainder split between the two brothers. At this point, however, the two brothers took up arms against each other. In 605, he invaded Theuderic's kingdom, but did not subdue it. He remained often at war with Theuderic until the latter died in Metz in late 613 while preparing a campaign against him.

In 604, a first attempt to reconquer his kingdom ended in failure for Clothar. His son Merovech was taken prisoner by Theuderic at the Battle of Étampes and was murdered at the order of Brunhilda by Bertoald. Clothar agreed that he would become the godfather of Theuderic's son in 607, naming him Merovech.[11]

Around the same time, Theuderic, seeking a marriage to the Spanish Visigoth princess Ermenberge, daughter of King Witteric, created new political tensions. Witteric then negotiated with Clothar II for an alliance, as well as Agilulf, King of the Lombards. The coalition against Theuderic does not appear to have been followed by significant effects.

War between Austrasia and Burgundy (610–612)

In 610 Theudebert and Theuderic entered into a war. Theudebert won initial victories in 610, which led Theuderic to approach Clothar, promising to return northern Neustria to him for his aid. Theudebert was crushed in 612, at the battles of Toul and Tolbiac, near Cologne.

War between Clothar and Austrasia-Burgundy (613)

As agreed, Theuderic ceded northern Neustria to Clothar, but then turned around and organized an invasion of Neustria. However he died of dysentery in Metz in 613. His troops dispersed immediately, and Brunhilda placed her great-grandson Sigebert II on the throne of Austrasia.[12]

At that time, Warnachar, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, and Rado, mayor of the palace of Burgundy, abandoned the cause of Brunhilda and her great-grandson, Sigebert II, and the entire realm was delivered into Chlothar's hands. Brunhilda and Sigebert met Chlothar's army on the Aisne, but the Patrician Aletheus, Duke Rocco, and Duke Sigvald deserted the host and the grand old woman and her king had to flee. They got as far as the Orbe, but Chlothar's soldiers caught up with them by the lake Neuchâtel. Both of them and Sigebert's younger brother Corbo were executed by Chlothar's orders, then proceeded to execute many of the family members of this house except Merovech, his godson, and perhaps Childebert who had fled.

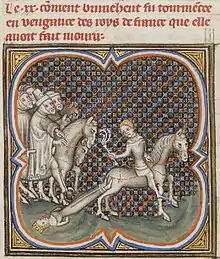

Brunhilde was accused of murdering ten members of the Neustrian royal family, as well as other Frankish royalty, and was tried and convicted. She underwent a very severe torture and execution by being dragged on the back of a horse and drawn-and-quartered.[13] After this victory, Clothar was left as the sole royal ruler of the Frankish peoples and consolidated his power.

King of All Franks (613–629)

Upon his unification of all Franks, Clothar took up residence in Paris and in the villas of Alentours.[14]

Mayors of the Palace

An important key aspect that was maintained in all three administrations of the kingdoms even after unification was the presence of the Mayors of the Palace. The mayor of the palace was originally the king's servant in charge of administrative events of the palace. During the royal feud, however, the role grew in importance as more of a steward of lands to care more directly than the king could and was placed in the hands of aristocracy. One of the most notable figures in this role was Warnachaire, mayor of the palace of Burgundy in 613, who was one of the leaders responsible for capturing Brunhild, and held the position until his death in 626. Warnachaire's wife, Berthe, was likely a daughter of Clothar.[15]

Edict of 614

In 614, Chlothar II convoked the Council of Paris and promulgated the Edict of Paris, which reserved many rights to the Frankish nobles while it excluded Jews from all civil employment for the Crown.[16][17] The ban effectively placed all literacy in the Merovingian monarchy squarely under ecclesiastical control and also greatly pleased the nobles, from whose ranks the bishops were ordinarily exclusively drawn. Article 11 of the Edict states that it is to restore "peace and discipline in [the] kingdom" and "suppress rebellion and insolence". The edict was ratified for all three kingdoms. Owing to several abuses of powers by officials, many of whom had been appointed by Chilperic, several mandates were made, among them the requirement that officials must have come from the region they officiate over.[18]

Chlothar was induced by Warnachar and Rado to make the mayoralty of the palace a lifetime appointment at Bonneuil-sur-Marne, near Paris, in 617.

Dagobert King of Austrasia (623)

In 623, he gave the kingdom of Austrasia to his young son Dagobert I. This was a political move as repayment for the support of Bishop Arnulf of Metz and Pepin I, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, the two leading Austrasian nobles, who were effectively granted semi-autonomy.[19]

At the same time, Clothar made territorial changes by assigning the region of Reims to Neustria. But Dagobert, now the semi-autonomous king of Austrasia, negotiated its return in 626.

Barbarian and Christian relations

Clothar was no exception in the line of Merovingians of its history of family feuding. This was considered to be a very 'barbarian' custom. However, he was one of the few Merovingians that did not practice polygamy, instead remaining faithful to a single wife until her death. He remained respectful of the Church and its doctrines, keeping it as an ally. He likely tried to maintain himself as a pious king, inspired by the holiness of his uncle Guntram who had protected him and allowed him the throne.[20]

In 617, he renewed the treaty of friendship that bound the Frankish kings with the kings of the Lombards. He likely had the policy of maintaining good relations with Christianized-barbarian peoples so long as they kept good relations themselves with the Church.[21]

Death

Clothar died in 629 at age 45 and was buried, like his father, in the Saint Vincent Basilica of Paris, later incorporated into the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. His rule lasted longer than any other Merovingian king save for his grandfather, Chlothar I. Clothar's son Dagobert, who had been king of Austrasia, succeeded his father in Neustria and Burgundy. Dagobert's half-brother, Charibert, however became king of Aquitaine.

Family

He first married Haldetrude, with whom he had the following children:

- Merovech, who was captured during a campaign against Burgundy and killed on orders of Brunhilda.

- Emma, married in 618 to Eadbald († 640), King of Kent. Though recently it has been suggested that she may have instead been the daughter of Erchinoald, mayor of the palace in Neustria.[22]

- Dagobert I (c. 603–639), King of the Franks

His second wife, Bertrude, was likely the daughter of Richomer, patrician of the Burgundians, and Gertrude. This marriage produced:

- A son who died in infancy in 617.

- Bertha, wife of Warnachaire, mayor of the palace of Burgundy.

In 618, he married Sichilde, sister of Gomatrude, who later married Dagobert I, and probably sister of Brodulfe, who would later support Charibert II. From this marriage there was:

- Charibert II († 632), king of Aquitaine.

- Oda, a daughter.

Notes

- Also spelled Chlotar, Clothar, Clotaire, or Chlotochar

References

- Chlotar II. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Chlotar II | Merovingian king | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, book IV, 28

- Bruno Dumézil, La reine Brunehaut, Paris, éditions Fayard, 2008, p. 212.

- Frédégaire, Chronique, III, 93.

- Grégoire de Tours, Historia Francorum, VII,

- Grégoire de Tours, Historia Francorum, VII, 9.

- Grégoire de Tours, Historia Francorum, VII, 2.

- Grégoire de Tours, Historia Francorum, VII.

- Prætextatus (Bishop of Rouen) married Brunhilda and Merovech, so making an enemy of Fredegund.

- Fastes juifs, romains et françois [by J.B. Mailly].

- Oman, Charles. The Dark Ages, 476-918, Rivingtons, 1908, p. 174

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Chronique de Frédégaire, IV, 42 ; Continuation de la Chronique d'Isidore.

- Lebecq, p. 126.

- For the mayors of the palace, cf. Lebecq, pp. 125–126.

- Alan Harding, Medieval Law and the Foundations of the State, (Oxford University Press, 2001), 14.

- S. Wise Bauer, The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), 251.

- The word used is judex, "judge", that is to say the earl or one of his subordinates. Cf. Lebecq, p. 125.

- Lebecq, p. 127.

- Histoire de France de l'Abbé Velly, Tome I (1752), pp. 244–247

- Histoire de France de l'Abbé Velly, Tome I (1752), p. 247

- Rollason, Mildrith Legend, p. 9.

Bibliography

Period sources

- Chronicles of the time of King Dagobert (592–639). translation by François Guizot and Romain Fern, Paleo, Clermont – Ferrand, "Sources of the history of France", 2004, ISBN 2913944388

- Fredegaire, Chronicle of Merovingian Times, translation by O. DeVilliers and J. Meyers, Brepols Publishing, 2001 ISBN 2503511511

- Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks

Contemporary studies

General Works

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1972). Merovingian Military Organization, 481–751. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 0816606218

- Deflou, Noelle Leca, and Alain Dubreucq (eds.) Societies in Mid-Late Sixth–Ninth Century Europe. Atlande, coll. Key Contest 2003 (biographies : " Chilperic ", " Fredegonde ", " Brunhild "), 575 pp. ISBN 978-2912232397

- Geary, Patrick J. (1988). Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 0195044584

- James, Edward (1991). The Franks. London: Blackwell, ISBN 0631148728

- Lebecq, Stéphane. The Frankish Origins Points / Seuil, 1990, pp. 117–119 (Part 1, Chapter 5 . "Royal feud (561–603)") and pp. 122–130; Part II, Chapter 1: "Clothar II and Dagobert (613–639)."

- Oman, Charles (1914). The Dark Ages, 476–918. London: Rivingtons

- Settipani, Christian. The Prehistory of the Capetians (New genealogical history of the august house of France, vol. 1), ed. Patrick van Kerrebrouck, 1993, ISBN 2950150934, pp. 92–100

- Volkmann, Jean-Charles. Known genealogy of the kings of France, Gisserot Publishing, 1999, ISBN 2877472086

- Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. (1962). The Long-Haired Kings, and Other Studies in Frankish History. London: Methuen

- Wood, Ian N. (1994). The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450–751. London: Longman, ISBN 0582218780

On Clothar II

- Ivan Gobry, Clothar II, Editions Pygmalion al. " History of the Kings of France ", 2005 ISBN 2857049668

External links

- Pfister, Christian (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 557.