Louis XII

Louis XII (27 June 1462 – 1 January 1515) was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Marie of Cleves, he succeeded his second cousin once removed and brother-in-law, Charles VIII, who died childless in 1498.

| Louis XII | |

|---|---|

Portrait by workshop of Jean Perréal, c. 1514 | |

| King of France | |

| Reign | 7 April 1498 – 1 January 1515 |

| Coronation | 27 May 1498 |

| Predecessor | Charles VIII |

| Successor | Francis I |

| Duke of Milan | |

| Reign | 6 September 1499 – 16 June 1512 |

| Predecessor | Ludovico Sforza |

| Successor | Massimiliano Sforza |

| King of Naples | |

| Reign | 2 August 1501 – 31 January 1504 |

| Predecessor | Frederick |

| Successor | Ferdinand III |

| Born | 27 June 1462 Château de Blois |

| Died | 1 January 1515 (aged 52) Hôtel des Tournelles |

| Burial | 4 January 1515 |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... | Claude, Queen of France Renée, Duchess of Ferrara Michel Bucy, Archbishop of Bourges (ill.) |

| House | Valois-Orléans |

| Father | Charles, Duke of Orléans |

| Mother | Marie of Cleves |

Before his accession to the throne of France, he was known as Louis of Orléans and was compelled to be married to his disabled and supposedly sterile cousin Joan by his second cousin, King Louis XI. By doing so, Louis XI hoped to extinguish the Orléans cadet branch of the House of Valois.[1][2]

Louis of Orléans was one of the great feudal lords who opposed the French monarchy in the conflict known as the Mad War. At the royal victory in the Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier in 1488, Louis was captured, but Charles VIII pardoned him and released him. He subsequently took part in the Italian War of 1494–1498 as one of the French commanders.

When Louis XII became king in 1498, he had his marriage with Joan annulled by Pope Alexander VI and instead married Anne of Brittany, Duchess of Brittany in her own right and the widow of his cousin Charles VIII. This marriage allowed Louis to reinforce the personal Union of Brittany and France.

Louis persevered in the Italian Wars, initiating a second Italian campaign for the control of the Kingdom of Naples. Louis conquered the Duchy of Milan in 1500 and pushed forward to the Kingdom of Naples, which fell to him in 1501. Proclaimed King of Naples, Louis faced a new coalition gathered by Ferdinand II of Aragon and was forced to cede Naples to Spain in 1504.

Louis XII did not encroach on the power of local governments or the privileges of the nobility, in opposition with the long tradition of the French kings to attempt to impose absolute monarchy in France. A popular king, Louis was proclaimed "Father of the People" (French: Le Père du Peuple) for his reduction of the tax known as taille, legal reforms, and civil peace within France.

Louis, who remained Duke of Milan after the second Italian War, was interested in further expansion in the Italian Peninsula and launched a third Italian War (1508–1516), which was marked by the military prowess of the Chevalier de Bayard.

Louis XII died in 1515 without a male heir. He was succeeded by his cousin and son-in-law Francis I from the Angoulême cadet branch of the House of Valois.

Early life

Louis d'Orléans was born on 27 June 1462 in the Château de Blois, Touraine (in the modern French department of Loir-et-Cher).[3] The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Marie of Cleves. His father was almost seventy years old when Louis was born. Louis was only three years old when he succeeded as Duke of Orléans upon the death of his father in 1465.[4]

Louis XI, who had become king of France in 1461, became highly distrustful of the close relationship between the Orleanists and the Burgundians and began to oppose the idea of an Orleanist ever coming to the throne of France.[5] However, Louis XI might have been more influenced in this opinion by his opposition to the entire Orleanist faction of the royal family than by the actual facts of this paternity case. Despite any alleged doubts that King Louis XI had, the King, nevertheless, became "godfather" of the newborn.[5]

King Louis XI died on 30 August 1483.[6] He was succeeded to the throne of France by his thirteen-year-old son, Charles VIII.[7] Nobody knew the direction which the new king (or more accurately his regent and oldest sister, Anne of France) would take in leading the kingdom. Accordingly, on 24 October 1483, a call went out for a convocation of the Estates General of the French kingdom.[8] In January 1484, deputies of the Estates General began to arrive in Tours, France. The deputies represented three different "estates" in society. The First Estate was the Church; in France this meant the Roman Catholic Church. The Second Estate was composed of the nobility and the royalty of France. The Third Estate was generally composed of commoners and the class of traders and merchants in France. Louis, the current Duke of Orleans and future Louis XII, attended as part of the Second Estate. Each estate brought its chief complaints to the Estates General in hopes to have some impact on the policies that the new King would pursue.

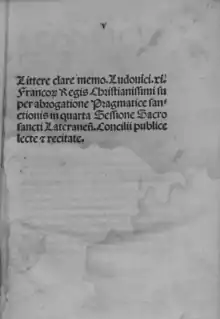

The First Estate (the Church) wanted a return to the "Pragmatic Sanction".[9] The Pragmatic Sanction had been first instituted by King Charles VII, the former King Charles VIII's grandfather. The Pragmatic Sanction excluded the papacy from the process of appointing bishops and abbots in France. Instead, these positions would be filled by appointment made by the cathedrals and monastery chapters themselves.[9] All church prelates within France would be appointed by the King of France without reference to the pope.

The deputies representing the Second Estate (the nobility) at the Estates General of 1484 wanted all foreigners to be prohibited from command positions in the military.[9] The deputies of the Third Estate (the merchants and traders) wanted taxes to be drastically reduced and that the revenue needs of the crown be met by reducing royal pensions and the number of offices.[9] All three of the estates were in agreement on the demand for an end to the sale of government offices.[9] By 7 March 1484, the King announced that he was leaving Tours because of poor health. Five days later the deputies were told that there was no more money to pay their salaries, and the Estates General meekly concluded its business and went home. The Estates General of 1484 is called, by historians, the most important Estates General until the Estates General of 1789.[10] Important as they were, many of the reforms suggested at the meeting of the Estates General were not immediately adopted. Rather the reforms would only be acted on when Louis XII came to the throne.

Since Charles VIII was only thirteen years of age when he became king, his older sister Anne was to serve as regent until Charles VIII became 20 years old. From 1485 through 1488, there was another war against the royal authority of France conducted by a collections of nobles. This war was the Mad War (1485–1488), Louis's war against Anne.[11] Allied with Francis II, Duke of Brittany, Louis confronted the royal army at the Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier on 28 July 1488 but was defeated and captured.[12] Pardoned three years later, Louis joined his cousin King Charles VIII in campaigns in Italy,[13] leading the vanguards of the army.

All four children of Charles VIII by Anne of Brittany died in infancy. The French interpretation of the Salic Law permitted claims to the French throne only by male agnatic descendants of French kings. This made Louis, the great-grandson of King Charles V, the most senior claimant as heir of Charles VIII. Thus, Louis, Duke of Orleans, succeeded to the throne on 7 April 1498 as Louis XII upon the death of King Charles VIII.[14]

Reign

Governance

Although he came late[15] (and unexpectedly) to power, Louis acted with vigour, reforming the French legal system,[16] reducing taxes,[17] and improving the government[18] much like his contemporary Henry VII did in England. To meet his budget after having reduced taxes, Louis XII reduced the pensions for the nobility and for foreign princes.[19] In religious policy, Louis XII reinstituted the Pragmatic Sanction, which established the Roman Catholic Church in France as a "Gallic Church" with most of the power of appointment in the hands of the king or other French officials. As noted above, these reforms had been proposed at the meeting of the Estates General in 1484.

Louis was also skilled in managing his nobility, including the powerful Bourbon faction, greatly contributing to the stability of French government. In the Ordinance of Blois of 1499[20] and the Ordinance of Lyon issued in June 1510[21] he extended the powers of royal judges and made efforts to curb corruption in the law. Highly complex French customary law was codified and ratified by the royal proclamation of the Ordinance of Blois of 1499.[22] The Ordinance of Lyon tightened up the tax collection system requiring, for instance, that tax collectors forward all money to the government within eight days after they collected it from the people.[23] Fines and loss of office were prescribed for violations of this ordinance.

Early wars

The French Kingdom under Charles VIII invaded Italy in 1494 to protect the Duchy of Milan from the threats of the Republic of Venice. At the time, the Duchy of Milan was one of the most prosperous regions of Europe.[24] Louis, the current Duke of Orleans and future King Louis XII, joined Charles VIII on this campaign. The French Kingdom was responding to an appeal for assistance from Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. The invasion set off a series of wars that would last from 1494 until 1559 and would become known as the "Italian Wars".

In 1495, Ludovico Sforza betrayed the French by changing sides in the war and joining the anti-French League of Venice (sometimes called the "Holy League").[25] This left Louis, the Duke of Orleans, in an awkward and inferior military position at the Battle of Fornovo on 6 July 1495. As a result, Louis had come to hate Ludovico Sforza.[26] Accordingly, even before he became King of France, Louis began to claim the Duchy of Milan as his own inheritance, which should have come to his by right of his paternal grandmother Valentina Visconti.

On this occasion he tried to conquer the Duchy of Milan, weakened by an economic crisis, and on 11 June 1495 he occupied with his troops the city of Novara,which was given to him for treason. He was on the verge of subjugating the Moro, who proved unable to cope with the situation, but clashed with the fierce opposition of his wife Beatrice d'Este, who forced him to a long and exhausting siege from which he finally came out defeated.[27][28]

After becoming king in 1499, Louis XII pursued his ambition to claim Milan in what is known as the "Great Italian War" (1499–1504) or "King Louis XII's War". However, before initiating any war Louis XII needed to deal with the international threats that he faced. In August 1498, he signed a peace treaty with the Emperor Maximillian I of the Holy Roman Empire.[29]

With Maximillian I neutralized, Louis wanted to turn his attention to King Henry VII of England. However, Henry was then pursuing a marriage between his eldest son, Arthur, and Catherine of Aragon, the Infanta of Spain.[29] Thus he needed to detach Spain from its close relations with England before he could deal with Henry VII. Furthermore, Spain was then a member of the anti-French League of Venice. Ferdinand of Aragon, king of the newly unified Spain, directed all relations between Spain and the French on behalf of himself and his queen, Isabella I of Castile.[29] Ferdinand was so hostile to France that he had founded the anti-French League of Venice in 1495.[30] In August 1498, Louis XII succeeded in signing a treaty with Spain that ignored all the territorial disputes between France and Spain and merely pledged mutual friendship and non-aggression.[31]

This allowed enough freedom for Louis XII to start negotiating with Scotland for an alliance. Actually, Louis was merely seeking to revive the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland that had been in existence since King Philippe IV of France first recognised Robert the Bruce (1306–1329) as King of Scotland in 1309. In early 1499, the old alliance between Scotland and France was renewed[29] and the attentions of England were drawn northwards towards Scotland rather than southwards towards continental Europe.

With the major powers preoccupied or pledged to peace with France, Louis XII could attend to two other neighbours on his border: the Swiss Confederation and the Duchy of Savoy. In March 1499, Louis signed an agreement with the Swiss Confederation that promised 20,000 francs as an annual subsidy for simply allowing the French to recruit an unspecified number of troops in the Confederation.[31] In exchange, Louis promised to protect the Confederation from any aggression from Maximillian and the Holy Roman Empire. Louis opened negotiations with the Duchy of Savoy and by May 1499 had hammered out an agreement that allowed French troops to cross Savoy to reach the Duchy of Milan. The agreement with Savoy also allowed France to purchase supplies and to recruit troops in Savoy.[32] Finally, Louis was ready to march into Italy.

The French army had been a potent force in 1494 when Charles VIII had first invaded Italy. However, during the remainder of Charles VIII's reign, the army had been allowed to deteriorate through neglect. Ever since becoming king, Louis XII had been rebuilding the French army.[33] Now he could put it to use.

On 10 August 1499, after marching across Savoy and through the town of Asti, the French army crossed the border into the Duchy of Milan. Contrary to the wishes of the Second Estate (the nobles and royalty of France), expressed at the Estates General in 1484, this French army was being led by a foreigner, Gian Giacomo Trivulzio.[34] Marshall Trivulzio had been in the service of the French throne since the reign of Louis XI, but he had been born and raised in Milan.[34] The French army that Marshal Trivulzio now commanded consisted of 27,000 men of which 10,000 were mounted. The French army was also supplied with 5,000 Swiss mercenaries.[34] In the campaign of 1499, the French army surrounded the fortified town of Rocca di Arazzo in the western part of the Duchy of Milan. After five hours of bombardment by the French artillery batteries, the walls of Rocca di Arazzo were breached and the town was taken by the French. Louis XII had ordered his army to massacre the garrison and many civilians as a message to the other towns in the Duchy against resistance to the French army.[34] The legal rationale for the massacre at Rocca di Arazzo was that defenders of the town were traitors because they had risen up in arms against their rightful lord, Louis XII. The French repeated the episode at Annone, the next fortified town on the road to the city of Milan. This time the massacre had the desired effect, as three more fortified towns surrendered without a fight.[35] Marshall Trivulzio then brought the French Army up to the gates of town of Alessandro, and his batteries began battering the walls of the town on 25 August 1499. At first, a vigorous defense was mounted by the garrison, but on 29 August 1499, the city gave up and the garrison and the governor of the city slipped out of town before dawn.[35]

Marshal Trivulzio now became aware that the Venetian army, allies of the Duchy of Milan, were crossing into the Duchy from the east in an attempt to aid the Milanese army before it was too late. Accordingly, Marshal Trivulzio marched his army to Pavia, the last fortified town in the Duchy of Milan.[35] With French troops already near Pavia, a short distance west of the city of Milan, Lodovico Sforza determined that it was useless to continue resisting the French. Accordingly, on the night of 2 September 1499, Sforza and a band of cavalry fled Milan, heading northward to the Holy Roman Empire.[35] Louis XII, staying in Lyon, heard about the surrender of Milan on 17 September 1499. He immediately left Lyon and on 6 October 1499, Louis XII made his triumphant entry into Milan. Marshal Trevulzio presented the key to the city to Louis, who in turn appointed Marshal Trivulzio as the temporary French governor of Milan. Later, Louis appointed Georges d' Amboise as the permanent governor of Milan.[36] In an attempt to win popularity with the public in Milan, Louis lowered the old Sforza taxes by as much as one-third.[37]

Meanwhile, Ludovico Sforza had been gathering an army, mainly among the Swiss, to take Milan back. In mid-January 1500, his army crossed the border into the Duchy of Milan and marched toward the city of Milan.[38] Upon hearing the news of Sforza's return, some of his partisans in the city rose up. On 1 February 1500, Marshal Trivulzio decided that he could not hold the city, and the French retreated to the fortresses west of the city. Sforza was welcomed back into the city by a joyous crowd of his supporters on 5 February 1500.[39] Louis XII raised another army under Louis de La Trémoille and sent him to recapture Milan. By the time Trémoille reached the forts west of Milan where Marshal Trivulzio and his force were holding out, the French army had swollen to 30,000 men by recruitment along the way.[39] Many of these new recruits in the French army were Swiss mercenaries. The government of the Swiss Confederation heard about the coming battle and forbade any Swiss soldier from fighting against a fellow Swiss, which effectively subtracted all the Swiss from both sides for this particular battle. These troops then started to march back home to Switzerland. This had a much more damaging effect on Sforza's army, because his army was composed of a larger proportion of Swiss than the French army under La Trémoille.

Faced with the return of the French and his own greatly reduced force, Sforza decided to slip out of Milan as he had done previously. This time, however, Sforza was captured[40] and spent the rest of his life in a French prison. Despite Milan's openly warm welcome of Sforza (which Louis XII regarded as "treasonous"), Louis XII was very generous to the city in victory. While Sforza had been in charge of Milan, the export of grain had been forbidden. Now the French reopened the trade in grain, setting off a decade of prosperity in Milan.[41] Milan was to remain a French stronghold in Italy for twelve years.

Using Milan as his firmly established base, Louis XII began to turn his attention to other parts of Italy. The city of Genoa agreed to the appointment of Philip of Cleves, a cousin of Louis XII, as its new governor.[35] Additionally, the French king now began to espouse his claim to the Kingdom of Naples, though the legal rationale for this claim was weaker than for his claim to Milan, stemming only from his position as the successor to Charles VIII.[42] Nonetheless, Louis XII pursued the claim with vigor.

The presence of several French garrisons in southern Italy, the remnants of Charles VIII's first invasion of Italy, provided Louis XII with a toehold in southern Italy from which he hoped to enforce his claim to the Kingdom of Naples.[42] However, Louis first had to deal with a recurring problem in northern Italy. In 1406, the city of Pisa was conquered by Florence but had been in constant revolt almost ever since. In 1494, the Pisans successfully overthrew the Florentine governors of the city.[42] The Florentines requested aid from the French to recapture Pisa, as the city of Florence had long been an ally of France in Italian affairs. However, Louis and his advisers were miffed at Florence because in the recent fight against Sforza, Florence had chosen to abandon France and remain strictly neutral.[42] The French knew that they would need Florence in the coming campaign in the Kingdom of Naples – French troops would need to cross Florentine territory on their way to Naples and they would need Florentine agreement to do so. Accordingly, a French army including 600 knights and 6,000 Swiss infantrymen under the command of Sire de Beaumont was sent to Pisa. On 29 June 1500, a combined French and Florentine force laid siege to Pisa and set up batteries around the town.[43] Within a day of opening fire, the French batteries had knocked down 100 feet of the old medieval walls surrounding the city. Even with the breach in their walls, the Pisans put up such a determined resistance that Beaumont despaired of ever taking Pisa. On 11 July 1500, the French broke camp and retreated north.[43] The diversion to Pisa and the failure there emboldened opponents of the French in Italy. Pursuing the claim to the Kingdom of Naples had become politically impossible until some of the opponents were neutralized. One opponent in particular was Spain. It was at this point, in 1500, that Louis XII pursued the claim of his immediate predecessor to the Kingdom of Naples with Ferdinand II, the King of Aragon and with Queen Isabel of Castile, ruler of Spain.

On 11 November 1500, Ferdinand II and Louis XII signed the Treaty of Granada,[44] which brought Spain into Italian politics in a big way for the first time. Louis XII was severely criticized by contemporary historians including Niccolò Machiavelli;[44] Machiavelli's criticism of Louis XII is contained in his work The Prince.

As portrayed in Machiavelli's The Prince

Louis's failure to hold on to Naples prompted a commentary by Niccolò Machiavelli in his book, The Prince:

King Louis was brought into Italy by the ambition of the Venetians, who expected by his coming to get control of half the state of Lombardy. I don't mean to blame the king for his part in the scheme; he wanted a foothold in Italy, and not only had no friends in the province, but found all doors barred against him because of King Charles's behavior. Hence he had to take what friendships he could get; and if he had made no further mistakes in his other arrangements, he might have carried things off very successfully. By taking Lombardy, the king quickly regained the reputation lost by Charles. Genoa yielded, and the Florentines turned friendly, the Marquis of Mantua, the Duke of Ferrara, the Bentivogli (of Bologna), the countess of Forlì (Caterina Sforza), the lords of Faenza, Pesaro, Rimini, Camerino, Piombino, and the people of Lucca, Pisa, and Siena all sought him out with professions of friendship. At this point the Venetians began to see the folly of what they had done, since in order to gain for themselves a couple of districts in Lombardy, they had now made the king master of a third of Italy.

Consider how easy it would have been for the king to maintain his position in Italy if he had observed the rules [of not worrying about weaker powers, decreasing the strength of a major power, not introducing a very powerful foreigner in the midst of his new subjects and taking up residence among his new subjects and/or setting up colonies], and become the protector and defender of his new friends. They were many, they were weak, some of them were afraid of the Venetians, others of the Church, hence they were bound to stick by him; and with their help, he could easily have protected himself against the remaining great powers. But no sooner was he established in Milan than he took exactly the wrong tack, helping Pope Alexander to occupy the Romagna. And he never realized that by this decision he was weakening himself, driving away his friends and those who had flocked to him, while strengthening the Church by adding vast temporal power to the spiritual power which gives it so much authority. Having made this first mistake, he was forced into others. To limit the ambition of Alexander and keep him from becoming master of Tuscany, he was forced to come to Italy himself [in 1502]. Not satisfied with having made the Church powerful and deprived himself of his friends, he went after the kingdom of Naples and divided it with the king of Spain (Ferdinand II). And where before he alone had been the arbiter of Italy, he brought in a rival to whom everyone in the kingdom who was ambitious on his own account or dissatisfied with Louis could have recourse. He could have left in Naples a caretaker king of his own, but he threw him out, and substituted a man capable of driving out Louis himself.

If France could have taken Naples with her own power, she should have done so; if she could not, she should not have split the kingdom with the Spaniards. The division of Lombardy that she made with the Venetians was excusable, since it gave Louis a foothold in Italy; the division of Naples with Spain was an error, since there was no such necessity for it. [When Louis made the final mistake of] depriving the Venetians of their power (who never would have let anyone else into Lombardy unless they were in control), he thus lost Lombardy.

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince,[45] Chapter III

Military campaigns against the Kingdom of Naples (1501–1508)

To assert his claim to his half of the Kingdom of Naples, Louis XII sent an army under the command of Bernard Stuart of Aubigny composed of 1,000 lances, 10,000 infantrymen including 5,000 Swiss troops to Naples in early June 1501.[46] In May 1501, Louis had obtained free passage for his troops to march through Bologne on the way to Naples.[46] As the army approached Rome, Spanish and French ambassadors notified Pope Alexander VI of the thus far secret Treaty of Grenada, signed 11 November 1500, which divided the Kingdom of Naples between France and Spain. The Pope was pleased and enthusiastically issued a bull naming the two kings – Louis XII of France and Ferdinand II of Spain – as the Pope's vassals in Naples.[46] Indeed, the public announcement of the treaty in the Vatican was the first news that King Frederick of Naples had received about his fate and his betrayal by his own cousin, Ferdinand.

Being a stern disciplinarian, Lord Stuart held the troops of his army to strict decorum during most of the march to Naples. However, discipline fell apart when the army passed through Capua. The French army plundered and raped Capua mercilessly.[46] However, when news of the rape of Capua spread throughout southern Italy, resistance to the French vanished. Frederick fled and the French Army entered Naples unopposed. Louis XII claimed the throne of Naples and pursuant to the sharing agreement with Ferdinand II shared half the income of Naples with Spain. However, as Machiavelli had predicted, the agreement could not last and in early 1502 relations between France and Spain had gone sour.[47] Negotiations were started between France and Spain over their disagreements about Naples. However, in April 1502, without waiting for the conclusion of these negotiations, Louis sent an army under the command of Louis d' Armagnac, Duke of Nemours against the Spanish in Apulia.[48]

War of the League of Cambrai

Louis's greatest success came in the War of the League of Cambrai (1508–1516), his final war, fought against the Venetians, who had again become his enemy. The French army won the Battle of Agnadello on 14 May 1509. However, things became much more difficult in 1510, when the army of Pope Julius II intervened.[49] Julius II founded the Holy League of the League of Cambrai specifically to thwart the ambitions of France. The French were eventually driven from Milan in 1513 by the Swiss.

Propaganda

Under Louis XII, there was an unprecedented explosion of propaganda and publicity for the French crown.[50] Louis XII had numerous large ceremonies for the various marriages, funerals, and other events that occurred under his reign. These occasions provided Louis with opportunities to project royal power and elevate Louis, which was largely done through iconography. Furthermore, while these royal images flooded the kingdom, popular writers – encouraged by Louis's lack of censorship – disseminated praise of their king.

Louis adopted the porcupine as his personal badge and as a royal beast. As a result, the popularity of the now royal creature exploded, resulting in the placement of porcupines in illuminated manuscripts, on edifices, and on cannons.[51] As it was common belief at the time that the porcupine could shoot its quills, the porcupine symbolized the offensive and defensive capabilities of the king.[52] During his years of conquest, Louis portrayed his kingdom to the public as a porcupine – a supposedly invincible creature feared by all. However, by the second half of his reign, Louis began to relegate the aggressive porcupine into a simple heraldic symbol for identification. Seeking to paint himself as a pious and chivalrous king to the public, Louis adopted titles such as Father of the People and compared himself to figures like St. Louis to highlight his commitment to justice and reform rather than simply military dominance.[53]

Louis's initial of L was often decorated with an open royal crown and laced with fleurs-de-lys. In addition, Louis's personal colors were red and yellow (or gold). Thus, guard regiment uniforms, manuscript color schemes, flags, often adorned Louis's royal colors and his initial.[54]

Moreover, Louis popularized the state portrait as a propaganda tool.[55] He employed numerous artists to capture him and produce individualized, miniature portraits that can be found in manuscripts today.[55] Furthermore, Louis's propaganda arsenal was greatly expanded with the addition of portrait coins – first minted in France in 1514.[56]

Legacy

Under Louis's reign, the province of Brittany finally became a de facto permanent province of France – although this was not legally completed until 1547.[57] At the end of his reign the crown deficit was no greater than it had been when he succeeded Charles VIII in 1498, despite several expensive military campaigns in Italy. His fiscal reforms of 1504 and 1508 tightened and improved procedures for the collection of taxes.

In spite of his military and diplomatic failures, Louis proved to be a popular king. Historians often attribute Louis's popularity to his tax reduction policies.[57] While Francis I eventually raised taxes, Louis's redaction of law codes and the creation of new parlements were longer-lasting. He duly earned the title of Father of the People ("Le Père du Peuple") conferred upon him by the Estates in 1506. This was the first and only time that a French king was bestowed the specific honorific of Father of the People.[58]

Family

Marriages

.jpg.webp)

Mary Tudor during her brief period as Queen of France

Mary Tudor during her brief period as Queen of France

In 1476 he was forced by King Louis XI (his second cousin) to marry his daughter Joan of France. Charles VIII (son of Louis XI) succeeded to the throne of France in 1483, but died childless in 1498, when the throne passed to Louis XII. Charles had been married to Anne, Duchess of Brittany, in order to unite the quasi-sovereign Duchy of Brittany with the Kingdom of France. To sustain this union, Louis XII had his marriage to Joan annulled (December 1498) after he became king so that he could marry Charles VIII's widow, Anne of Brittany.

The annulment, described as "one of the seamiest lawsuits of the age", was not simple. Louis did not, as one might have expected, argue the marriage to be void due to consanguinity (the general allowance for the dissolution of a marriage at that time). Though he could produce witnesses to claim that the two were closely related due to various linking marriages, there was no documentary proof, merely the opinions of courtiers. Likewise, Louis could not argue that he had been below the legal age of consent (fourteen) to marry: no one was certain when he had been born, with Louis claiming to have been twelve at the time, and others ranging in their estimates between eleven and thirteen. As there was no real proof, he had perforce to bring forward other arguments.

Accordingly, Louis (much to the dismay of his wife) claimed that Joan was physically malformed (providing a rich variety of detail precisely how) and that he had therefore been unable to consummate the marriage. Joan, unsurprisingly, fought this uncertain charge fiercely, producing witnesses to Louis's boast of having "mounted my wife three or four times during the night". Louis also claimed that his sexual performance had been inhibited by witchcraft. Joan responded by asking how he was able to know what it was like to try to make love to her. Had the Papacy been a neutral party, Joan would likely have won, for Louis's case was exceedingly weak. Pope Alexander VI, however, had political reasons to grant the annulment, and ruled against Joan accordingly. He granted the annulment on the grounds that Louis did not freely marry, but was forced to marry by Joan's father Louis XI. Outraged, Joan reluctantly submitted, saying that she would pray for her former husband. She became a nun; she was canonized in 1950.

Louis married the reluctant queen dowager, Anne, in 1499. Still only 22, Anne, who had borne as many as seven stillborn or short-lived children during her previous marriage to King Charles, now bore a further four stillborn sons to the new king, but also two surviving daughters. The elder daughter, Claude (1499–1524), was betrothed by her mother's arrangement to the future Emperor Charles V in 1501. But after Anne failed to produce a living son, Louis dissolved the betrothal and betrothed Claude to his heir presumptive, Francis of Angoulême, thereby insuring that Brittany would remain united with France. Anne opposed this marriage, which took place only after her death in 1514. Claude succeeded her mother in Brittany and became queen consort to Francis. The younger daughter, Renée (1510–1575), married Duke Ercole II of Ferrara.

After Anne's death, Louis married Mary Tudor, the sister of Henry VIII of England, in Abbeville, France, on 9 October 1514. This represented a final attempt to produce an heir to his throne, for despite two previous marriages the king had no living sons. Louis died on 1 January 1515, less than three months after he married Mary, reputedly worn out by his exertions in the bedchamber, but more likely from the effects of gout. Their union produced no children, and the throne passed to Francis I of France, who was Louis's first cousin once removed, and also his son-in-law.

Issue

| By Anne of Brittany | |||||||||||||||

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claude of France | 14 October 1499 | 20 July 1524 | Married Francis I of France on 18 May 1514; had issue. | ||||||||||||

| Unnamed son | late 1500/early 1501 | died young | Père Anselme records that in 1501 King Louis XII sent “le cardinal d’Amboise” to Trentino to negotiate a marriage between his son and one of the daughters of Philip I of Castile;[59]: 128 however, he cites no primary source for this statement. If it is correct, the son in question must have been different from the one who was born 21 January [1503/07] who is shown below. | ||||||||||||

| Unnamed son | 21 January [1503/07] | 21 January [1503/07] | The Journal de Louise de Savoie records that “Anne reine de France” gave birth at Blois 21 January to “un fils...il avoit faute de vie”.[60] The entry does not specify the year but follows an entry for 1502 and precedes one for 1507. Kerrebrouck dates the event to 1503 “à l’issue d’un voyage à Lyon” but does not specify the primary source on which he bases this information.[61] | ||||||||||||

| Renée of France | 25 October 1510 | 12 June 1574 | Married Ercole II d'Este in April 1528;[62] had issue. | ||||||||||||

| Unnamed son | January [1513] | January [1513] | Père Anselme records a second son “mort en bas âge”, without dates or primary source citations.[59]: 128 Kerrebrouck records a son “mort-né au château de Blois janvier 1512”, commenting that “[la] grossesse [de la reine] tourne mal” after Pope Julius II excommunicated Louis XII for refusing to negotiate the liberation of the papal legate whom the French had captured after the Battle of Ravenna.[61] As the battle happened took place on 11 April 1512, Kerrebrouck's date is presumably Old Style. This birth is not mentioned in the Journal de Louise de Savoie.[63] | ||||||||||||

Louis XII had an illegitimate son, Michel Bucy, Archbishop of Bourges, from 1505, who died in 1511 and was buried in Bourges.[64][65]

Death

On 24 December 1514, Louis was reportedly suffering from a severe case of gout.[66] In the early hours of 1 January 1515, he received the final sacraments and died later that evening.[66] On 11 January Louis's body was taken to the Notre-Dame for a funeral mass. The next day, during the funeral procession, the cart carrying the coffin broke down and there was a dispute over which party would receive the gold cloth that covered the coffin.[67] Louis was interred in Saint Denis Basilica.[68] He is commemorated by the Tomb of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany.

Succession

The succession to the throne of France followed Salic Law, which did not allow women to inherit the throne. As a result, Louis XII was succeeded by Francis I. Born to Louise of Savoy, on 12 September 1494, Francis I was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême. Francis would also marry Louis XII's eldest daughter Claude of France.

The succession to the ducal crown of Brittany followed semi-Salic tradition, allowing women to inherit the crown in their own right (suo jure). Anne of Brittany predeceased Louis XII. Thus, Anne's eldest daughter, Claude of France, inherited the Duchy of Brittany directly in her own right (suo jure) before Louis's death. When Claude married Francis I, Francis also became the administrator of Brittany in right of his wife. This assured that Brittany would remain part of the Kingdom of France and the unity of the Kingdom would be upheld.

Honours

.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of France – Grand Master of the Order of Saint Michael

Kingdom of France – Grand Master of the Order of Saint Michael.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of France – Duchy of Orléans : Last Grand Master and Knight of the Order of the Porcupine

Kingdom of France – Duchy of Orléans : Last Grand Master and Knight of the Order of the Porcupine

Media

- As Duke of Orleans, he is a recurring character in Sir Walter Scott's 1823 novel Quentin Durward, where he is portrayed as attempting to break his marriage contract to Joan.

- Louis is portrayed by English actor Joseph Beattie in the Canal+ series Borgia (TV series). He continues the claim on Naples by Charles VIII, and is also crowned Duke of Milan by Cesare Borgia. Despite his initial friendship with Cesare, their relations are strained by Cesare's conflicts with French interests, as well as Cesare's heavy-handed methods. After della Rovere becomes Pope Julius II and Cesare's downfall begins, Louis offers him exile in France, but Cesare's ambition refuses to consider defeat.

- The first season of The Tudors contains a plotline based loosely on Louis' final marriage. Mary is renamed Margaret, to avoid confusion with her niece of the same name, and concessions were made to the altered political landscape of the fictionalized series. The first season starts with Francis I already King of France, but in order to include Mary's short royal marriage and scandalous secret remarriage, the writers added a King of Portugal as her bridegroom, who bears no resemblance to the King of Portugal at that time. The marriage is still quite short, as 'Margaret' smothers her husband with a pillow.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Louis XII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- André Vauchez, Michael Lapidge, "Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages: A-J", pp. 776, 2000: "Infirm from birth, she was obliged by her father, Louis XI, to marry her cousin, Louis of Orleans. The king wished, by a union considered sterile, to extinguish this rival collateral dynasty."

- "The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, Volume 33", pp. 42, 1854: "Louis XI compelled him to marry his deformed and sterile daughter Joan, threatening him with death by drowning, if he refused."

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 1.

- Susan G. Bell, The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies, (University of California Press, 2004), 105.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 3.

- Kendall 1971, p. 368.

- Kendall 1971, p. 373.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 21.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 22.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 23.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 27–31.

- Malcolm Walsby, The Counts of Laval: Culture, Patronage and Religion in Fifteenth-and Sixteenth Century France, (Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2007), 37.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 39–49.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 51–56.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 56.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, pp. 88–90.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 100–101.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 84–87.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 102.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 95.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 202–204.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 95–97.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 203.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 40.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 46.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 105.

- Marin Sanudo, La spedizione di Carlo VIII in Italia, Mancia del Commercio di M. Visentini, 1883, pp. 438, 441.

- Bernardino Corio, L'Historia di Milano, Giorgio de' Cavalli, 1565, pp. 1095–1099.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 106.

- Rhea Marsh Smith, Spain: A Modern History, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1965), p. 113.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 107.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 108.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 109.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 113.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 114.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 117.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 115.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 115–116.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 116.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 116–117.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 118.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 119.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 120.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 122.

- The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli. Translated and edited by Robert M. Adams. A Norton Critical Edition. New York: 1977. pp. 9–11.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 123.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 125.

- Baumgartner 1996, pp. 125–126.

- Norwich, John Julius (1989). A History of Venice. New York: Vintage Books. p. 415. ISBN 0679721975.

- Baumgartner. Louis XII. p. 249.

- Scheller, Robert (1983). "Ensigns of Authority: French Royal Symbolism in the Age of Louis XII". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 13 (2): 79. doi:10.2307/3780504. JSTOR 3780504.

- Hochner, Nicole (2001). "Louis XII and the porcupine: Transformations of a royal emblem". Renaissance Studies. 15 (1): 19. doi:10.1111/1477-4658.00354. S2CID 159885190 – via JSTOR.

- Hochner. "Louis XII and the porcupine: Transformations of a royal emblem": 36.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Scheller. "Ensigns of Authority: French Royal Symbolism in the Age of Louis XII": 80.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Scheller. "Ensigns of Authority: French Royal Symbolism in the Age of Louis XII": 82.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Scheller. "Ensigns of Authority: French Royal Symbolism in the Age of Louis XII": 88.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Baumgartner 1996, p. 246.

- Scheller, Robert (1983). "Ensigns of Authority: French Royal Symbolism in the Age of Louis XII". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 13 (2): 95. doi:10.2307/3780504. JSTOR 3780504.

- Anselme de Sainte-Marie, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires.

- Michaud & Poujoulat (1838), Tome V, Journal de Louise de Savoye, p. 87.

- Kerrebrouck, P. van (1990). Les Valois (Nouvelle histoire généalogique de l'auguste Maison de France) ISBN 978-2950150929, pp. 167, 175 footnote 44.

- C. W. Previté-Orton, Cambridge Medieval History, Shorter: Volume 2, The Twelfth Century to the Renaissance, (Cambridge University Press, 1978), 776.

- Michaud & Poujoulat (1838), Tome V, Journal de Louise de Savoye, p. 89.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 175.

- (FR) Gabriel Peignot, De la maison royale de France, (Renouard, Libraire, rue-Saint-Andre-Des-arcs, 1815), 151.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 143.

- Baumgartner. Louis XII. p. 244.

- Baumgartner 1996, p. 244.

- de Gibours 1726, pp. 105–106.

- de Gibours 1726, pp. 205–208.

- de Gibours 1726, pp. 109–110.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Daniel Meredith (1941). Giangaleazzo Visconti: Duke of Milan : 1351–1402. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–9.

- Dahm, Helmut (1953), "Adolf I.", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 1, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 80–81; (full text online)

- Ornato, Monique (1981). Répertoire de personnages apparentés à la couronne de France aux XIVe et XVe siècles [Directory of characters related to the crown of France in the 14th and 15th centuries]. Publications de la Sorbonne. p. 145. ISBN 978-2859444426.

- Walther Möller, Stammtafeln westdeutscher Adelsgeschlechter im Mittelalter (Darmstadt, 1922, reprint Verlag Degener & Co., 1995), Vol. 1, p. 14.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 445.

- Backhouse, Janet (1997). The illuminated page: ten centuries of manuscript painting in the British Library. p. 166.

- von Oefele, Edmund (1875), "Albrecht I. (Herzog von Niederbayern-Straubing)", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), vol. 1, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 230–231

Bibliography

- de Gibours, Anselm (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires.

- Ashley, Maurice, Great Britain to 1688: A Modern History (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1961).

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. (1996). Louis XII. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312120729.

- Guérard, Albert, France: A Modern History (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1959).

- Hochner, Nicole, Louis XII: Les dérèglements de l’image royale, collection "Époques" Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2006 Accueil

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1971). Louis XI: The Universal Spider. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

.svg.png.webp)