Louis XI

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (French: le Prudent), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII. Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revolt known as the Praguerie in 1440. The king forgave his rebellious vassals, including Louis, to whom he entrusted the management of the Dauphiné, then a province in southeastern France. Louis's ceaseless intrigues, however, led his father to banish him from court. From the Dauphiné, Louis led his own political establishment and married Charlotte of Savoy, daughter of Louis, Duke of Savoy, against the will of his father. Charles VII sent an army to compel his son to his will, but Louis fled to Burgundy, where he was hosted by Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, Charles' greatest enemy.

| Louis XI | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| King of France | |

| Reign | 22 July 1461 − 30 August 1483 |

| Coronation | 15 August 1461, Reims |

| Predecessor | Charles VII |

| Successor | Charles VIII |

| Born | 3 July 1423 Bourges, Berry, France |

| Died | 30 August 1483 (aged 60) Château de Plessis-lez-Tours, France |

| Burial | 6 September 1483 Notre-Dame de Cléry Basilica, Cléry-Saint-André |

| Spouses | |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | Valois |

| Father | Charles VII of France |

| Mother | Marie of Anjou |

| Signature |  |

When Charles VII died in 1461, Louis left the Burgundian court to take possession of his kingdom. His taste for intrigue and his intense diplomatic activity earned him the nicknames "the Cunning" (Middle French: le rusé) and "the Universal Spider" (Middle French: l'universelle aragne), as his enemies accused him of spinning webs of plots and conspiracies.

In 1472, the subsequent Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, took up arms against his rival Louis. However, Louis was able to isolate Charles from his English allies by signing the Treaty of Picquigny (1475) with Edward IV of England. The treaty formally ended the Hundred Years' War. With the death of Charles the Bold at the Battle of Nancy in 1477, the dynasty of the dukes of Burgundy died out. Louis took advantage of the situation to seize numerous Burgundian territories, including Burgundy itself and Picardy.

Without direct foreign threats, Louis was able to eliminate his rebellious vassals, expand royal power, and strengthen the economic development of his country. He died in 1483, and was succeeded by his minor son Charles VIII.

Childhood

Louis was born in Bourges on 3 July 1423, the son of King Charles VII of France.[1] At the time of the Hundred Years War, the English held northern France, including the city of Paris, and Charles VII was restricted to the centre and south of the country.[2] Louis was the grandson of Yolande of Aragon, who was a force in the royal family for driving the English out of France, which was at a low point in its struggles. Just a few weeks after Louis's christening at the Cathedral of St. Étienne on 4 July 1423, the French army suffered a crushing defeat by the English at Cravant.[3] Shortly thereafter, a combined Anglo-Burgundian army threatened Bourges itself.

During the reign of Louis's grandfather Charles VI (1380–1422), the Duchy of Burgundy was very much connected with the French throne, but because the central government lacked any real power, all the duchies of France tended to act independently.[4] In its position of independence from the French throne, Burgundy had grown in size and power. By the reign of Louis's father Charles VII, Philip the Good was reigning as duke of Burgundy, and the duchy had expanded its borders to include all the territory in France from the North Sea in the north to the Jura Mountains in the south and from the Somme River in the west to the Moselle River in the east.[5] During the Hundred Years War, the Burgundians allied themselves with England against the French crown.[6]

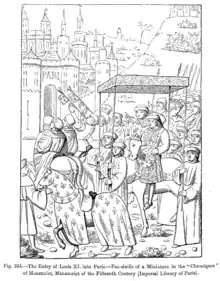

In 1429, young Louis found himself at Loches in the presence of Joan of Arc, fresh from her first victory over the English at the Siege of Orléans,[3] which initiated a turning point for the French in the Hundred Years War. Joan later led troops in other victories at the Battle of Jargeau and the Battle of Patay.[6] Paris was recaptured after her death, and Louis and his father were able to ride in triumph into the city on 12 November 1437.[7] Nevertheless, Louis grew up aware of the continuing weakness of France. He regarded his father as a weakling, and despised him for this.

Marriages

On 24 June 1436, Louis met Margaret, daughter of King James I of Scotland, the bride his father had chosen for diplomatic reasons.[9] There are no direct accounts from Louis or his young bride of their first impressions of each other, and it is mere speculation whether they actually had negative feelings for each other. Several historians think that Louis had a predetermined attitude to hate his wife, but it is universally agreed that Louis entered the ceremony and the marriage itself dutifully, as evidenced by his formal embrace of Margaret upon their first meeting.

Louis's marriage with Margaret resulted from the nature of medieval royal diplomacy and the precarious position of the French monarchy at the time. The wedding ceremony—very plain by the standards of the time—took place in the chapel of the castle of Tours on the afternoon of 25 June 1436, and was presided over by Renaud of Chartres, the Archbishop of Reims.[10] The 13-year-old Louis clearly looked more mature than his 11-year-old bride, who was said to resemble a beautiful doll and was treated as such by her in-laws.[10] Charles wore "grey riding pants" and "did not even bother to remove his spurs".[10] The Scottish guests were quickly hustled out after the wedding reception, as the French royal court was quite impoverished at this time. They simply could not afford an extravagant ceremony or to host their Scottish guests for any longer than they did. The Scots, however, saw this behaviour as an insult to their small but proud country.[11]

Following the ceremony, "doctors advised against consummation" because of the relative immaturity of the bride and bridegroom. Margaret continued her studies, and Louis went on tour with Charles to loyal areas of the kingdom. Even at this time, Charles was taken aback by the intelligence and temper of his son. During this tour, Louis was named Dauphin of France by Charles, as was traditional for the eldest son of the king.[11] The beautiful and cultured Margaret was popular at the court of France, but her marriage to Louis was not a happy one, in part because of his strained relations with her father-in-law, who was very attached to her. She died childless at the age of 20 in 1445.

In 1440, Louis, aged 16, took part in an uprising known as the Praguerie, which sought to neutralize Charles and install Louis as regent of France. The uprising failed, and Louis was forced to submit to the king, who chose to forgive him.[12] In this revolt, Louis came under the influence of Charles I, Duke of Bourbon,[13] whose troops were in no condition to mount such a serious threat to royal authority. Louis was forced to retreat to Paris, but was "by no means trounced".[14] In fact, before his final defeat, "[Louis's]...military strength, combined with antipathy of the masses for great lords, won him the support of the citizens of Paris."[14] This was a great learning experience for Louis. James Cleugh notes:

Like other strong-minded boys, he had found at last he could not carry all before him by mere bluster. Neither as prince nor as king did he ever forget his lesson. He never acted on pure impulse, without reflection, though to his life’s end he was constantly tempted to take such a risk.[10]

In 1444, Louis led an army of "écorcheurs" (bands of mercenary soldiers) against the Swiss at the Battle of St. Jakob an der Birs where he sought to reconquer territories of his future brother-in-law, Sigismund of Austria-Tyrol.[15] He won only one victory before suing for peace.[15] He failed to achieve his original objective.[15]

He still quarreled with his father. His objectionable scheming, which included disrespectful behavior directed against his father's beloved mistress Agnès Sorel,[16] caused him to be ordered out of court on 27 September 1446 and sent to his own province of Dauphiné. He lived mainly in Grenoble, in the tour de la Trésorerie.[17] Despite frequent summons by the king, the two would never meet again. In Dauphiné, Louis ruled as king in all but name,[18] continuing his intrigues against his father. On 14 February 1451, Louis, who had been widowed for six years, made a strategic marriage to the eight-year-old Charlotte of Savoy, without Charles' consent.[19] This marriage was to have long-ranging effects on foreign policy as the beginning of French involvement in the affairs of the Italian peninsula.

Finally, in August 1456, Charles sent an army to Dauphiné under the command of Antoine de Chabannes. Louis fled to Burgundy, where he was granted refuge by Duke Philip the Good and settled in the castle of Genappe.[20] King Charles was furious when Philip refused to hand over Louis and warned the duke that he was "giving shelter to a fox who will eat his chickens."

Accession

In 1461, Louis learned that his father was dying. He hurried to Reims to be crowned, in case his brother, Charles, Duke of Berry, should try to do the same. Louis XI became King of France on 22 July 1461.[21]

Louis pursued many of the same goals that his father had, such as limiting the powers of the dukes and barons of France, with consistently greater success. Among other initiatives, Louis instituted reforms to make the tax system more efficient.[22] He suppressed many of his former co-conspirators, who had thought him their friend, and he appointed to government service many men of no rank, but who had shown promising talent. He particularly favored the associates of the great French merchant Jacques Coeur.[22] He also allowed enterprising nobles to engage in trade without losing their privileges of nobility.[22] He eliminated offices within the government bureaucracy, and increased the demand on other offices within the government in order to promote efficiency.[22] Louis spent a large part of his kingship on the road.[23] Travelling from town to town in his kingdom, Louis would surprise local officials, investigate local governments, establish fairs, and promote trade regulations.[24] Perhaps the most significant contribution of Louis XI to the organization of the modern state of France was his development of the system of royal postal roads in 1464.[25] In this system, relays at instant service to the king operated on all the high roads of France; this communications network spread all across France and led to the king acquiring his nickname "Universal Spider".[26]

As king, Louis became extremely prudent fiscally, whereas he had previously been lavish and extravagant. He wore rough and simple clothes and mixed with ordinary people and merchants. A candid account of some of his activities is recorded by the courtier Philippe de Commines in his memoirs of the period. Louis made a habit of surrounding himself with valuable advisers of humble origins, such as Commines himself, Olivier Le Daim, Louis Tristan L'Hermite, and Jean Balue. Louis was anxious to speed up everything, transform everything, and build his own new world.[22] In recognition of all the changes that Louis XI made to the government of France, he has the reputation of a leading "civil reformer" in French history, and his reforms were in the interests of the rising trading and mercantile classes that would later become the bourgeoisie classes of France.

Louis XI also involved himself in the affairs of the Church in France. In October 1461, Louis abolished the Pragmatic Sanction that his father had instituted in 1438 to establish a French Gallican Church free of the controls of the popes in Rome.[27]

Feud with Charles the Bold

Philip III was the Duke of Burgundy at the time that Louis came to the throne, and was keen to initiate a Crusade against the Ottoman Empire. However, he needed funds to organize such an enterprise. Louis XI gave him 400,000 gold crowns for the Crusade in exchange for a number of territories, including Picardy and Amiens.[28] However, Philip's son, the future Charles I, Duke of Burgundy (known as the Count of Charolais at the time of Louis's accession) was angry about this transaction, feeling that he was being deprived of his inheritance. He joined a rebellion called the League of the Public Weal, led by Louis's brother Charles, the Duke of Berry.[29] Although the rebels were largely unsuccessful in battle, Louis had no better luck. Louis XI fought an indecisive battle against the rebels at Montlhéry[30] and was forced to grant an unfavourable peace as a matter of political expediency.[31]

When the Count of Charolais became Duke of Burgundy in 1467 as Charles I ("the Bold"), he seriously considered declaring an independent kingdom of his own. However, Louis's progress toward a strong centralized government had advanced to the point where the dukes of Burgundy could no longer act as independently as they had in the past. The duchy now faced many problems and revolts in its territories, especially from the people of Liège, who conducted the Liège Wars against the Duke of Burgundy. In the Liège Wars, Louis XI allied himself at first with the people of Liège.

In 1468, Louis and Charles met at Péronne, but during the course of negotiations, they learned that the citizens of Liège had again risen up against Charles and killed the Burgundian governor.[32] Charles was furious. Philippe de Commines, at that time in the service of the duke of Burgundy, had to calm him down with the help of the duke's other advisors for fear that he might hit the king. Louis was forced into a humiliating treaty. He gave up many of the lands he had acquired from Philip the Good, turned on his erstwhile allies in Liège and swore to help Charles put down the uprising in Liège. Louis then witnessed a siege of Liège in which hundreds were massacred.[33]

However, once out of Charles's reach, Louis declared the treaty invalid, and set about building up his forces. His aim was to destroy Burgundy once and for all. Nothing was more odious to Louis' dream of a centralized monarchy than the existence of an over-mighty vassal such as the Duke of Burgundy. War broke out in 1472. Duke Charles laid siege to Beauvais and other towns. However, these sieges proved unsuccessful; the Siege of Beauvais was lifted on 22 July 1472,[34] and Charles finally sued for peace. Philippe de Commines was then welcomed into the service of King Louis.

In 1469, Louis founded the Order of St. Michael, probably in imitation of the prestigious Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Charles' father Philip the Good, just as King John II of France had founded the now defunct Order of the Star in imitation of the Order of the Garter of King Edward III of England. In both cases, a French king appears to have been motivated to found an order of chivalry to increase the prestige of the French royal court by the example of his chief political adversary.

Dealings with England

| Coin of Louis XI, struck ca. 1470 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse: Medieval image of Louis XI | Reverse: Fleurs-de-lis |

At the same time that France and Burgundy were fighting each other, England was experiencing a bitter civil conflict now known as the Wars of the Roses. Louis had an interest in this war, for the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, was allied with the Yorkists who opposed King Henry VI. When the Earl of Warwick fell out with the Yorkist King Edward IV, after helping Edward attain his throne, Louis granted Warwick refuge in France. Through Louis's diplomacy, Warwick then formed an alliance with his bitter enemy Margaret of Anjou in order to restore her husband Henry VI to the throne. The plan worked, and Edward was forced into exile in 1470, but he later returned to England in 1471. Warwick was then killed at the Battle of Barnet in 1471.[35] King Henry VI was soon murdered afterwards.[35]

Now the undisputed master of England, Edward invaded France in 1475,[36] but Louis was able to negotiate the Treaty of Picquigny, by which the English army left France in return for a large sum of money. The English renounced their claim to French lands such as Normandy, and the Hundred Years' War could be said to be finally over. Louis bragged that although his father had driven the English out by force of arms, he had driven them out by force of pâté, venison, and good French wine.

Outcome of rivalry with Charles the Bold

Just as his father had done, Louis spent most of his reign dealing with political disputes with the reigning Duke of Burgundy,[26] and for this purpose he employed the Swiss,[37] whose military might was renowned. He had admired it himself at the Battle of St. Jakob an der Birs.

War broke out between Charles and the Swiss after he invaded Switzerland.[38] The invasion proved to be a tremendous mistake. On 2 March 1476, the Swiss attacked and defeated the Burgundians first at Grandson[39] and then again a few months later, on June 22 of the same year, at Murten.[40] The duke was killed at the Battle of Nancy on 5 January 1477, an event that marked the end of the Burgundian Wars.[41]

Louis was thus able to see the destruction of his sworn enemy. Those lords who still favored the feudal system gave in to his authority. Others, such as Jacques d'Armagnac, Duke of Nemours, were executed. The lands belonging to the Duchy of Burgundy as constituted by Louis's great-great-grandfather John II for the benefit of his son Philip the Bold reverted to the crown of France.

Italian connections

The marriage on 14 February 1451 between 28-year-old Louis and the 8-year-old Charlotte of Savoy was the true beginning of French involvement in the affairs of Italy. The Italian peninsula was a compact and politically competitive space dominated by five powers: Venice, Milan, Florence, the Papacy, and the Kingdom of Naples.[42] Beside these five great regional powers, there were about a dozen smaller states in Italy that were constantly changing policies and shifting alliances between and towards the various regional powers. The city/state of Genoa and the rising state of Savoy, which centered on the city of Turin, were examples of these lesser powers in northern Italy. Even the Italic League—the combination of the five major powers of Italy that had been born out of the Treaty of Lodi of 1454—was constantly undergoing internal realignments.[43]

Both Louis XI and his father Charles VII had been too busy with their struggles with Burgundy to pay much attention to political affairs smoldering in Italy. Additionally, Louis had his attention drawn away from Italy by disagreements with the rulers of England and his struggles with Maximilian of Austria, who married the heir of Charles the Bold, Mary of Burgundy, and wanted to keep her territorial inheritance intact. However, the death of the Duke of Burgundy in 1477,[44] which conclusively settled the issue of Burgundy's position under the French throne, the conclusion of the Treaty of Picquigny with England in 1475 and the peaceful resolution in 1482 of the disposition of the "Burgundian inheritance" left to Mary of Burgundy finally allowed Louis XI to turn his attention to Italy.[45]

Viewed from the Italian states, the death of the Duke of Burgundy in 1477 and the resultant downfall of his duchy as a threat to the French throne signalled vast changes in the states' relationships with the kingdom of France.

Despite his connection by marriage to the royal house of Savoy, Louis XI continuously courted a strong relationship with Francesco I Sforza, the Duke of Milan, who was a traditional enemy of Savoy. As a confirmation of the close relationship between Milan and the king of France, Sforza sent his son Galeazzo Maria Sforza to aid Louis XI in his war against the League of Public Weal in 1465 at the head of a large army.[46] Later, differences arose between France and Milan that caused Milan to seek ways of separating itself from dependence on the French. However, with the downfall of Burgundy in 1477, France was seen in a new light by Milan, which now hurriedly repaired its relationship with Louis XI.[43] Likewise, France's old enemy King Ferdinand I of Naples began to seek a marriage alliance between the Kingdom of Naples and France.[43] Louis XI also opened new friendly relations with the Papal States, forgetting the past devotion of the popes for the Duke of Burgundy.[43] In January 1478, he signed a favorable treaty with the Republic of Venice.

French involvement in the affairs of Italy would be carried to new levels by Louis XI's son Charles VIII in 1493, when he answered an appeal for help from Ludovico Sforza, the younger son of Francesco Sforza, that led to an invasion of Italy. This would become a significant turning point in Italian political history.[47]

Death

Louis XI, having suffered from bouts of apoplexy and years of illness, died on 30 August 1483[48] and was interred in the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Cléry[49] in Cléry-Saint-André in the Arrondissement of Orléans. His widow, Charlotte, died a few months later, and is interred with him. Louis XI was succeeded by his son Charles VIII, who was thirteen years of age. Louis' eldest daughter, Anne, became regent on Charles' behalf.

Legacy

Eager to obtain information about his enemies, Louis created, from 1464, a net of postal relays all over France,[25] which was a precursor to the modern French postal service.

Louis developed his kingdom by encouraging trade fairs and the building and maintenance of roads. Louis XI pursued the organization of the kingdom of France with the assistance of bourgeois officials.[26] In some respects, Louis XI perfected the framework of the modern French Government which was to last until the French Revolution.[26] Thus, Louis XI is one of the first modern kings of France who helped take it out of the Middle Ages.

Louis XI was very superstitious[50] and surrounded himself with astrologers. Interested in science, he once pardoned a man sentenced to death on condition that he serve as a guinea pig for a gallstone operation.

Through wars and guile, Louis XI overcame France's mostly independent feudal lords, and at the time of his death in the Château de Plessis-lez-Tours, he had united France and laid the foundations of a strong monarchy. He was, however, a secretive, reclusive man, and few mourned his death.

Despite Louis XI's political acumen and overall policy of Realpolitik, Niccolò Machiavelli criticized him harshly in Chapter 13 of The Prince, calling him shortsighted and imprudent for abolishing his own infantry in favor of Swiss mercenaries.

Children

Louis and Charlotte of Savoy had:

- Louis (18 October 1458 – 1460)

- Joachim (15 July 1459 – 29 November 1459)

- Louise (born and died in 1460)

- Anne (3 April 1461 − 14 November 1522), married in 1473, Peter of Beaujeu[51]

- Joan (23 April 1464 – 4 February 1505), married Louis XII, King of France[52]

- Louis (born and died on 4 December 1466)

- Charles VIII of France (30 June 1470 – 8 April 1498)[52]

- Francis, Duke of Berry (3 September 1472 – November 1473)

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Louis XI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Kendall 1971, p. 33.

- Guérard 1959, p. 552.

- Kendall 1971, p. 34.

- Guérard 1959, p. 105.

- Kendall 1971, p. 84.

- Kendall 1971, p. 42.

- Kendall 1971, p. 46.

- Châtelet & Paviot 2007, pp. 401, 410.

- Kendall 1971, p. 43.

- Cleugh 1970, p. ??.

- Tyrell 1980, p. ??.

- Kendall 1971, p. 50.

- Kendall 1971, p. 48.

- Le Roy Ladurie 1987, p. ??.

- Hardy, Duncan (2012). "The 1444–5 expedition of the Dauphin Louis to the Upper Rhine in geopolitical perspective". Journal of Medieval History. 38 (3): 358–387. doi:10.1080/03044181.2012.697051. ISSN 0304-4181. S2CID 154109619.

- Kendall 1971, pp. 65–67.

- Moreau 2010, p. ??.

- Kendall 1971, p. 69.

- Kendall 1971, p. 75.

- Kendall 1971, p. 86.

- Kendall 1971, p. 107.

- Kendall 1971, p. 116.

- Kendall 1971, p. 115.

- Kendall 1971, p. 118.

- Thompson 1995, p. 64.

- Guérard 1959, p. 116.

- Kendall 1971, p. 117.

- Kendall 1971, p. 121.

- Kendall 1971, p. 142.

- Kendall 1971, pp. 158–168.

- Kendall 1971, p. 169.

- Kendall 1971, p. 214.

- Kendall 1971, pp. 222–223.

- Kendall 1971, p. 250.

- Kendall 1971, p. 241.

- Kendall 1971, p. 276.

- Guérard 1959, p. 117.

- Kendall 1971, p. 298.

- Kendall 1971, p. 300.

- Kendall 1971, p. 305.

- Kendall 1971, p. 314.

- Kendall 1971, p. 333.

- Kendall 1971, p. 334.

- Guérard 1959, pp. 117–118.

- Kendall 1971, p. 323.

- Kendall 1971, p. 147.

- Hoyt & Chodorow 1976, p. 619.

- Bakos 1997, p. 9.

- Brine 2015, p. 68.

- Bowersock 2009, p. 64.

- Hand 2013, p. 26.

- Kendall 1971, p. 385.

- Anselm 1726, pp. 105–106.

- Anselm 1726, pp. 109–110.

- Riezler, Sigmund Ritter von (1893), "Stephan III.", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), vol. 36, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 68–71

- Anselm 1726, pp. 111–114.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1978). A Distant Mirror. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc. p. 145. ISBN 978-0394400266.

Sources

- Bakos, Adrianna E. (1997). Images of Kingship in Early Modern France: Louis XI in Political Thought, 1560–1789. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4151-5478-9.

- Bowersock, G W (2009). From Gibbon to Auden : Essays on the Classical Tradition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1997-0407-1.

- Brine, Douglas (2015). Pious Memories: The Wall-Mounted Memorial in the Burgundian Netherlands. Brill. ISBN 978-9-0042-8832-4.

- Châtelet, Albert; Paviot, Jacques (2007). Visages d'antan : le Recueil d'Arras (XIVe–XVIe siècle). Éditions du Gui. ISBN 978-2-9517-4176-8.

- Cleugh, James (1970). Chant Royal The Life of King Louis XI of France (1423–1483). Doubleday & Company, Inc. ASIN B000NX3VVY.

- de Gibours, Anselm (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires.

- Guérard, Albert (1959). France: A Modern History. University of Michigan Press. ASIN B00G0N283I.

- Hand, Joni M. (2013). Women, Manuscripts and Identity in Northern Europe, 1350–1550. Ashgate Publishing.

- Hoyt, Robert S.; Chodorow, Stanley (1976). Europe in the Middle Ages. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc. ISBN 978-0-1552-4713-0.

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1971). Louis XI: The Universal Spider. W.W. Norton & Company Inc. ISBN 978-1-8421-2411-6.

- Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel (1987). The Royal French State 1460–1610. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-6311-7027-3.

- Moreau, Gilles-Marie (2010). Le Saint-Denis des Dauphins: histoire de la collégiale Saint-André de Grenoble (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-2961-3062-3.

- Saenger, Paul. "Burgundy and the Inalienability of Appanages in the Reign of Louis XI." French Historical Studies 10.1 (1977): 1–26 online.

- Slattery, Maureen. "King Louis XI-Chivalry's Villain or Anti-Hero: the Contrasting Historiography of Chastellain and Commynes." Fifteenth Century Studies 23 (1997): 49+.

- Thompson, John B. (1995). The Media and Modernity: A Social Theory of the Media. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-5674-8.

- Tyrell, Joseph M. (1980). Louis XI. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7728-4.