Childebert II

Childebert II (c.570[1]–596) was the Merovingian king of Austrasia (which included Provence at the time) from 575 until his death in March 596, as the only son of Sigebert I and Brunhilda of Austrasia; and the king of Burgundy from 592 to his death, as the adopted son of his uncle Guntram.

| Childebert II | |

|---|---|

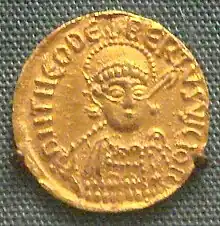

Tremissis of Childebert II | |

| King of Austrasia | |

| Reign | 575–596 |

| Predecessor | Sigebert I |

| Successor | Theudebert II |

| King of Burgundy | |

| Reign | 592–596 |

| Predecessor | Guntram |

| Successor | Theuderic II |

| Born | 570 |

| Died | 596 (aged 25–26) |

| Spouses | Faileuba |

| Issue | Theudebert II Theuderic II |

| House | Merovingian |

| Father | Sigebert I |

| Mother | Brunhilda |

Childhood

When his father was assassinated in 575 by two slaves of Queen-consort Fredegund of Soissons,[2] Childebert was taken from Paris by Gundobald (according to one story, after being lowered from a window in a bag by his mother[3]), one of his faithful lords, to Metz (the Austrasian capital), where he was recognized as sovereign. He was then only five years old, and during his long minority the power was disputed between his mother Brunhilda and the nobles,[4][5] with Brunhilda being dominant until Childebert came of age in 585.

Chilperic I, king at Paris, and the Burgundian king Guntram, sought an alliance with Childebert, who was adopted by both in turn.[2][5] Because Guntram was lord of half of Marseille, the district of Provence became a centre of a brief dispute between the two.

Guntram allied with Dynamius of Provence, who instigated the canons of the Diocese of Uzès to elect their deacon Marcellus, as bishop in opposition to their already-elected bishop Jovinus, a former governor of Provence. While Jovinus and Theodore, Bishop of Marseille, were travelling to the court of Childebert, Guntram had them arrested. Dynamius, meanwhile, blocked Gundulf, a duke of an important senatorial family and Childebert's former domesticus, from entering Marseille on behalf of Childebert. Eventually he was forced to yield, though he later arrested Theodore again and had him sent to Guntram. Childebert replaced him in Provence by Nicetius (585). Despite his revolt, Childebert formally restored Dynamius to favour on 28 November 587.

Heir, king and war leader

With the assassination of Chilperic in 584 and the dangers occasioned to the French monarchy by the expedition of Gundoald in 585, Childebert threw himself unreservedly to the side of Guntram. By the Treaty of Andelot of 587, Childebert was recognised as Guntram's heir, and with his uncle's help in 587 he quelled the revolt of Dukes Rauching, Ursio, and Berthefried,[6] and succeeded in seizing the castle of Woëvre.[7] Many attempts were made on his life by Fredegund, wife of Chilperic, who was anxious to secure Guntram's inheritance for her son Clotaire II. Childebert II had relations with the Byzantine Empire, and fought on several occasions in the name of the Emperor Maurice against the Lombards in Italy, with limited success.[8][5]

With Guntram, he authorized the Irish monk Saint Colomban to found the abbey of Luxeuil and two other monasteries in the heart of the Vosges and to work with his monks in the various missions and foundations in all the Frankish kingdoms.[9]

On the death of Guntram in 592, Childebert annexed the kingdom of Burgundy, and even contemplated seizing Clotaire's estates and becoming sole king of the Franks.[5] However, he and his young wife Faileuba died after being poisoned in 596. He had two young sons: the older, Theudebert II, inherited Austrasia with its capital at Metz, and the younger, Theuderic II, received Guntram's former kingdom of Burgundy, with its capital at Orléans.

References

- Childebert, A. C. Murray,The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity, ed. Oliver Nicholson, Vol. I, (Oxford University Press, 2018), 320.

- Van Dam. Raymond. "Merovingian Gaul and the Frankish conquests", The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, c. 500–c. 700, ed. Paul Fouracre, Rosamond Mac Kitterick, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 204.

- J. M. Wallace-Hadrill (1958). Fredegar and the History of France (PDF). p. 543.

- Gregory of Tours. Decem Libri Historiarum. Vol. V, VI.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Pfister, Christian (1911). "Childebert". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 137.

- Brandon Taylor Craft (2013). "Queenship, intrigue and blood-feud: deciphering the causes of the Merovingian civil wars, 561–613". Louisiana State University. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- Bruno Kursch (1882). "Zur Chronologie der Merowingischen Könige". Forschungen zur Deutschen Geschichte.

- Ian Wood, The Merovingian Kingdoms, (Longman, 1994), 167–168.

- Jean Prieur, Hyacinthe Vulliez (1999). La Fontaine de Siloé (ed.). Saints et saintes de Savoie (in French). pp. 19–23 on Saint Thècle and pp. 25–28 on Saint Gontran. ISBN 978-2842064655.