Alfonso II of Naples

Alfonso II (4 November 1448 – 18 December 1495) was Duke of Calabria and ruled as King of Naples from 25 January 1494 to 23 January 1495.[1] He was a soldier and a patron of Renaissance architecture and the arts.

| Alfonso II | |

|---|---|

Medal of Alfonso as Duke of Calabria by Adriano Fiorentino, 1481 | |

| King of Naples | |

| Reign | 25 January 1494 – 23 January 1495 |

| Predecessor | Ferdinand I |

| Successor | Ferdinand II |

| Born | 4 November 1448 Naples, Kingdom of Naples |

| Died | 18 December 1495 (aged 47) Mazara del Vallo, Kingdom of Sicily |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Ippolita Maria Sforza |

| Issue | |

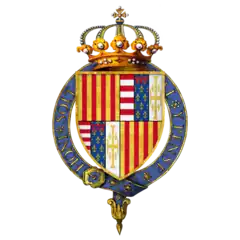

| House | Trastámara |

| Father | Ferdinand I, King of Naples |

| Mother | Isabella of Clermont |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Heir to his father Ferdinand I's Kingdom of Naples, Alfonso held the dukedom of Calabria for most of his life.[1] In the 1480s Alfonso commanded the Neapolitan forces in Tuscany in 1478–79. He helped reverse the Ottoman invasion of Otranto in Apulia in 1480–81, and against the Republic of Venice in 1484.[1] In 1486 Alfonso's repressive conduct towards the Neapolitan nobility prompted a revolt; the violent excesses of suppressing this uprising further discredited Alfonso and King Ferdinand. Under Alfonso's patronage the city of Naples was remodelled with new churches, straightened roads, and an aqueduct supplying fountains.[1]

Alfonso became King of Naples in 1494 on his father's death. Within a year he was forced by the approaching army of Charles VIII of France to abdicate; he was succeeded by his son Ferdinand II of Naples.[1] Alfonso went into an Olivetan monastery at Mazara del Vallo, on Sicily, where he survived until 18 December 1495.[1]

Biography

Born in Naples, Alfonso was the eldest child of Ferdinand I of Naples by his first wife, Isabella of Clermont.[2] In 1463, when Alfonso was fifteen, his maternal great uncle Giovanni Antonio del Balzo Orsini, Prince of Taranto, died, and he obtained some lands from the inheritance. When his mother died in 1465, he succeeded to her feudal claims, including the title King of Jerusalem.

Alfonso's education was at his father's humanist court.[1] His tutor between 1468 and 1475 was the humanist Giovanni Pontano, whose De principe describes the proper virtues and manner of life becoming to a prince; the work took the form of letter of advice to the twenty-year old Alfonso, then Duke of Calabria, in 1468.[3] Pontano dedicated a further treatise on courage, De fortitudine, to Alfonso in 1481, after his victory over the Ottoman invasion of Otranto, and remained close as his personal secretary until Alfonso's abdication.[3]

As a condottiero, Alfonso fought in the most important wars of the age, such the war following the Pazzi Conspiracy (1478–1480) and the War of Ferrara (1482–1484). Alfonso had shown himself a skilled and determined soldier, helping his father in the suppression of the conspiracy of the barons (1485) and in the defense of the Kingdom's territory against the Papal claims.

When his father died, the kingdom's finances were exhausted and the invasion of Italy by King Charles VIII of France was imminent.[4] Instigated by Lodovico Sforza, who wished to stir up trouble to allow him to seize power in Milan, and with papal support, Charles decided to reassert the Angevin claim to Naples. He invaded Italy in September 1494 and was able to move swiftly south along the peninsula. Alfonso managed to regain the support of Pope Alexander VI, who invited Charles to devote his effort against the Turks instead. Alfonso was crowned on 8 May 1494 by the papal legate Juan de Borja Lanzol de Romaní, el mayor.

Charles, however, did not relent; by early 1495 Charles was approaching Naples, after having defeated Florence and the Neapolitan fleet under Alfonso's brother Frederick at Porto Venere. Alfonso, terrified by a series of portents, as well as unusual dreams and despised by Neapolitans,[5] he abdicated in favor of his son, Ferdinand II. He then fled to a Sicilian monastery. He died in Messina later that year.

Appearance and personality

At a young age he was described by ladies and ambassadors as a very handsome young man, "So pretty you couldn't say", but "so alive that he couldn't sit still for half an hour".[6] Doctors and ambassadors were surprised by his physical endurance, as he was able to keep himself healthy while eating and drinking very little and often in a hurry, being continuously busy in different activities during the day and resting a few hours at night, which he spent continuously with his wife.[7]

He was nicknamed the Guercio by the people because he had his left eye marked, but it is not known whether from illness, from injury or from birth. According to other historians, this was instead because of his grim look and the habit of looking crooked. Francesco Pansa judges instead that he was squinting.[8]

He had exceptional military skills and spent most of his life on the battlefields, leading a soldier's life. Andrea Bernardi says that, following the death of the famous leader Roberto Sanseverino, Alfonso remained the first armigero of Italy.[9]

However, he was greatly feared and hated by the Neapolitan people for having offended their subjects with "most cruel insults and offenses", for having been guilty of the most heinous crimes, such as "violating virgins, taking other women for his pleasure" and practicing "Detesting and abominable vice of sodomy".[10]

For example, the anonymous author of the Chronicum venetum reports - but it should be remembered that the Venetians were sworn enemies of the Neapolitans and of the Aragones in particular - who "wanting to narrate tyranny, cruelty, lustful and dishonest appetites, betrayals, the assassinations, the murders of King Ferrante and of Alfonso d'Aragona, his eldest son, Duke of Calabria, father of betrayals, conservative of rebels, a great book would not be enough for me: I believe that Nero was a saint among these tyrants".[11]

Beyond the possible exaggerations of enemy faction, many episodes of Alfonso's life confirm these aspects of his character, such as the fact that he expropriated numerous lands without offering any compensation to the legitimate owners (who, it is said, died of pain) for the construction of the villa of Poggioreale, and that in the same way he evicted the nuns of La Maddalena for the construction of the villa called della Duchesca . He also obtained for the Como – family friends – the splendid garden that Francesco Scannasorice owned adjacent to their palace: the man had refused numerous times to cede the garden to the Como, despite the generous offers of money, but he did not dare to oppose a refusal to the fearsome Duke of Calabria. The Neapolitans were so terrified that at the death of King Ferrante they all ran to barricade themselves in the house shouting "inside! inside!", not even if they were chased by enemies.[12] His wife Ippolita Maria Sforza herself experienced its cruelty when, newly married, jealous of her husband, she sent her own trusted servant, Donato, to keep an eye on Alfonso in his travels, and Alfonso's reaction towards Donato was of such recklessness that Hippolyta wrote to her mother in her own letter: "This thing about Donato that I will never forget [...] not a wound to the heart, but I think it opened in the middle, so much was my pain and it will be".[13]

It was no coincidence that, when the situation of the kingdom became desperate, Alfonso decided to abdicate in favor of his son, since he was so hated for his vices and cruelty as vices Ferrandino loved for his virtues and justice.

Loves

According to the Successi tragici et amorosi by Silvio Ascanio Corona, a seventeenth-century collection of novels in which the secrets of the members of the Aragonese court of Naples are collected – or at least it seems – Alfonso was prodigal of loves, thus not differing from his father Ferrante.[14]

His first mistress was Isabella Stanza, bridesmaid of his mother Isabella of Chiaramonte; the relationship, however, did not last long. As soon as the mother – a very chaste and very religious woman – had a hint of the tresca, she married Isabella to Giovan Battista Rota, a nobleman very fond of the Aragonese faction, and thus to distance her from her son.[14]

After her, Alfonso had his best-known mistress, Trogia Gazzella, whom he led to court. Tired of Trogia, he fell in love with Francesca Caracciolo, called Ceccarella, who, faithful to her husband, did not correspond to him. Alfonso had her kidnapped and, for several days, abused her at will until the woman's father and husband urged King Ferrante to persuade his son to release her. Ceccarella then retired to the convent of San Sebastiano, where shortly after, she died of pain. Alfonso, outraged, then had her father, Muzio Caracciolo, slaughtered, while her husband Riccardo, fearing for his life, took the monastic habit.[14]

He then loved Maria d'Avellanedo, a Spanish noblewoman and bridesmaid of his stepmother Giovanna, then married to Alfonso Caracciolo, knight of the seat of Capuana, then a nobleman of the Montefuscolo family, then married to Galeotto Pagano of the seat of Porto, and Laura Crispano, whom he had by force and who he then married to his waiter Angelo Crivelli Milanese.[14]

He loved – so it was said – also the beautiful young people, and among them, Diego Cavaniglia, Giovanni Piscicelli and Onorato III Caetani (who was also his son-in-law). He was also romantically linked to some of his own pages. The practice of sodomy, according to the ancient Greek custom, was moreover widespread almost everywhere at that time, despite being officially prohibited, and its other relatives were not exempt from it.[14]

Renaissance culture

Alfonso participated in the brilliant Renaissance culture that surrounded his father's court. His lasting contribution to European culture was the example set at his villas of La Duchesca and especially Poggio Reale just outside Naples, which so captivated Charles VIII of France during his brief sojourn at Naples during February–June 1495, that he was inspired to emulation of the "earthly paradise" he encountered.[15]

Poggio Reale, which Giorgio Vasari said was designed by Giuliano da Maiano and was laid out in the 1480s, has utterly disappeared and no extensive description has survived. Decades later, Vasari reported, "At Poggio Reale [Giuliano da Maiano] laid out the architecture of that palazzo, always considered a most beautiful thing; and to fresco it he brought there Pietro del Donzello, a Florentine, and Polito his brother who was considered in that time a good master, who painted the whole palazzo, inside and out, with the history of the said king."[16] There are no archives to connect Giuliano or his brother Benedetto with the project; for documentation only a section and plan, reproduced with apologies for its inaccuracy, by Sebastiano Serlio. Serlio's reproduction seems to show an idealized plan,[17] identical on all four sides, ranged around a court with a double arcading.

It is clear that the Aragonese court at Naples introduced the Moorish garden traditions of Valencia, with its shaded avenues and baths, sophisticated hydraulics that powered splendid waterworks,[18] formal tanks, fishponds and fountains, as a luxurious and secluded setting for court life, and combined them with Roman features: Alfonso's Poggio Reale was built around three sides of an arcaded courtyard with tiers of seating round a sunken centre that could be flooded for water spectacles; on the fourth side it opened onto a garden that framed a spectacular view of Vesuvius.

It was all unlike anything experienced by the French king, who retreated from Italy, loaded with tapestries and works of art, and filled with building and gardening ambitions, but he would die young only three years later.

Marriage and children

Alfonso's wife was Ippolita Maria Sforza, whom he married on 10 October 1465 in Milan.[19] His mistress, by whom he also had children, was Trogia Gazzella.

He had three children with Ippolita:

- King Ferdinand II of Naples (26 August 1469 – October 1496), married Joanna of Naples

- Isabella of Aragon, Duchess of Milan and of Bari, Princess of Rossano (2 October 1470 – 11 February 1524), married her first cousin Gian Galeazzo Sforza, Duke of Milan, January 1490.[20]

- Piero, Prince of Rossano (31 March 1472 – 17 February 1491), Lieutenant General of Apulia, died of an infection following leg surgery.

And two with Trogia :

- Sancia of Aragon (born 1478 in Gaeta)

- Alfonso, Duke of Bisceglie and Prince of Salerno (born 1481 in Naples)

By Maria d'Avellanedo he had two sons, Francesco and Carlo, both of whom died at a young age.[14]

From Laura Crispano he had a little girl who died in swaddling clothes.[14]

In popular culture

Alfonso II of Naples is portrayed by Augustus Prew in the Showtime series The Borgias, although he is portrayed as much younger and flamboyant than his historical counterpart was in the 1490s. Sancia of Aragon is portrayed as his half-sister rather than his daughter. In the European series Borgia written by Tom Fontana, where he is played by Raimund Wallisch, his portrayal is more historically accurate in terms of his age and Sancia being his daughter. In Da Vinci's Demons he is played by Kieran Bew and is depicted as a sadistic warlord, bitterly jealous of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

William Shakespeare's play "The Tempest" features two fictional characters: "Alonso, King of Naples" and "Ferdinand, son to the King of Naples" who may have been named after Alfonso II and his son Ferdinand II.[21]

Notes

- Campbell, Gordon, ed. (2005) [2003]. "Alfonso II of Aragon". The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001. ISBN 9780191727795.

- Previté-Orton 1978, p. 767.

- Webb 1997, p. 69.

- Atlas, Allan W., Music at the Aragonese Court of Naples, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 5 ISBN 9780521088305

- Cognizioni elementari della Storia di Sicilia, part III; by Niccolo Gianfala, Reale Stamperia, Palermo page 57.

- Patrizia Mainoni (a cura di), Con animo virile, donne e potere nel Mezzogiorno medievale, Viella, pp. 393-397.

- Archivio Storico per le Province Napoletane, Nuova serie Anno IX. - XLVIII. dell'intera collezione, 1923; Leostello, effemeridi per lo duca di Calabria.

- Istoria dell'antica repubblica d'Amalfi e di tutte le cofe appartenenti alla medefima, accadute nella cittá di Napoli, e fuo regno. Con lo registro di tutti gli archivj dell'istessa · Volume 1.

- Cronache forlivesi dal 1476 al 1517, Volume 1, Numero 1, Di Andrea Bernardi, Giuseppe Mazzatinti · 1895, p. 199.

- Anonimo. Chronicum venetum.

- Anonimo. Chronicum venetum.

- Ciro Raia. Breve storia di re Ferrandino. Guida Editori.

- Ippolita Maria Sforza. Lettere. Edizioni dell'Orso. p. 34.

- Camillo Minieri Riccio, Catalogo di mss. della (sua) biblioteca, 1868.

- Charles' letter to his brother-in-law, Pierre de Bourbon, noted in William Howard Adams, The French Garden 1500–1800 1979, p. 10.

- "A Poggio Reale ordinò l'architettura di quel palazzo, tenuta sempre cosa bellissima; et a dipignerlo vi condusse Piero del Donzello fiorentino e Polito suo fratello che in quel tempo era tenuto buon maestro, il quale dipinse tutto il palazzo di dentro e di fuori con storie di detto re." (Giorgio Vasari, Le vie de' più eccelenti architetti, piiori...).

- Suggestions that its design was sketched by Alfonso's friend Lorenzo de' Medici, whose own villa at Poggio a Caiano it somewhat resembled, are tenuous.

- The first description of a surprise jet of water as a practical joke, a garden feature with a long career, was remarked on at Poggio Reale.

- Fallows 2010, p. 39.

- Black 2009, p. 83.

- "The Tempest :|: Open Source Shakespeare". www.opensourceshakespeare.org. Retrieved 2023-03-24.

References

- Black, Jane (2009). Absolutism in Renaissance Milan: Plenitude of Power Under the Visconti and the Sforza, 1329–1535. Oxford University Press.

- Fallows, Noel (2010). Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia. The Boydell Press.

- Hersey, George L. (1969). Alfonso II and the Artistic Renewal of Naples. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Previté-Orton, C. W. (1978). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 2, The Twelfth Century to the Renaissance (9th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Webb, Nicholas (1997). "Giovanni Pontano". In Kraye, Jill (ed.). Cambridge Translations of Renaissance Philosophical Texts. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–87.

- Brief description of Poggio Reale