Edward Cromwell, 3rd Baron Cromwell

Edward Cromwell, 3rd Baron Cromwell (c. 1559– 27 April 1607)[1][2] was an English peer. He was the son of Henry Cromwell, 2nd Baron Cromwell by his wife Mary, daughter of John Paulet, 2nd Marquess of Winchester and his first wife Elizabeth Willoughby. His grandfather, Gregory, son of Thomas Cromwell, chief minister to Henry VIII, was created Baron Cromwell on 18 December 1540.[1][3]

Edward Cromwell | |

|---|---|

| 3rd Baron Cromwell Kt PC | |

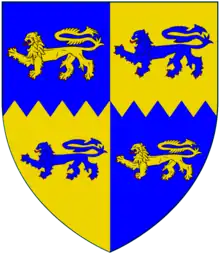

Arms of Cromwell, Baron Cromwell: Quarterly, per fess, indented, azure and or, four lions passant | |

| Tenure | 1592–1607 |

| Successor | Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Ardglass |

| Born | Edward Cromwell c. 1559 Launde Abbey, Leicestershire |

| Died | 27 April 1607 (aged 47–48) Downpatrick, County Down |

| Buried | Down Cathedral, Downpatrick 54.327061°N 5.722547°W |

| Nationality | English |

| Residence | Launde Abbey |

| Locality | Leicestershire |

| Offices | Governor of Lecale |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Upton Frances Rugge |

| Issue | with Elizabeth: Elizabeth Cromwell with Frances: Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Ardglass Frances Cromwell Anne Cromwell |

| Parents | Henry Cromwell, 2nd Baron Cromwell Mary Paulet |

Career

Cromwell spent some time at Jesus College, Cambridge, as the pupil of Richard Bancroft, afterwards archbishop of Canterbury, but did not matriculate. He was created M.A. at a special congregation in 1594.[4] In 1591 he acted as a colonel in the English army under Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, sent to aid Henry IV of France in Normandy, and on his father's death in 1592 succeeded to his peerage.[1][5]

He served as a volunteer in the naval expedition against Spain of 1597 and "sued hard ... for the government of the Brill" in 1598. He served in the expedition against Spain with Essex and was knighted by him in 1599, however, his hopes of becoming marshall of the army there were in vain.[1][6] In August 1599 it was reported that he had defeated a rebel force of six thousand men, but by the end of the month he was in London again.[3]

Edward Cromwell was caught up in Essex's rebellion, a futile attempt by the Earl of Essex, in January 1600 – 1601, to raise an insurrection in London. He was arrested for his role and sent to the Tower on 9 February 1601.[1] Cromwell "protesteth ignorance of the attempt, and that he casually fell into the Earl of Essex's company, nor was he any way partaker of any plot; which thing he protesteth may be proved by his dealing with the Lord Mayor’s."[7] Cromwell's wife "made humble suit to the council on behalf of her Lord that is a prisoner in the Tower, in regard that he is corpulent and sickly he may take the air." Her wish was granted permitting her husband, "from time to time to take the air, but only in the company of the Lieutenant and his deputy". Sir Charles Danvers, a key figure among the Essex intimates during the planning and execution of the rebellion, did not include Cromwell among "the names of such that manifested themselves in the action" that he gave to the Privy Council.[8] Cromwell and William Sandys, 3rd Baron Sandys (d. 1623) were brought for trial to Westminster Hall on 5 March 1601. Cromwell confessed his guilt, was fined £3,000 and imprisoned for several months, but received a special pardon from Elizabeth I on 2 July and was released on 9 July 1601.[1][3]

Having fallen into royal disfavour, faced with mounting debts, and troubled by lawsuits, Cromwell was having to sell off part of his lands. Though not debarred from taking his seat in Parliament, he was advised on 23 September 1601 by the privy council that it "is thought by her Majesty more convenient that you forbeare your comminge to the Parliament." Cromwell frequently petitioned Sir Robert Cecil in an attempt to get himself reconciled with the Queen. "To whom shall I complain, whose crimes have deprived me of everything- friends, allies, means. Alas, I know not, if God, her Majesty and you shall forsake me... I entreat you to read my petition and relieve my overthrown fortunes."[9]

On James I's accession, Cromwell was sworn of the privy council. The king "was daily troubled with the poor Lord Cromwell's begging leave to sell the last pieces of his land, who had valiantly served the State in the wars."[10] Cromwell alienated all of his English property to Charles Blount, lord Mountjoy, and settled in Ireland.[11] On 13 September 1605 Cromwell made an agreement with an Irish chief, Phelim McCartan, to receive a large part of the McCartan's territory in County Down on condition that he educated and provided for McCartan's son in his household. On 4 October 1605, McCartan and Cromwell, by arrangement, resigned their estates to the king, who formally regranted them to the owners, and Cromwell was at the same time made governor of Lecale.[3] He purchased the Barony of Lecale in 1606 and built an "imposing house" in Downpatrick, County Down.[1]

Marriages and issue

Edward Cromwell married firstly in 1581, Elizabeth Upton (died 5 January 1593, buried Launde Abbey, Leicestershire), daughter of William Upton of Puslinch, Devon, and Mary Kirkham, and had an only daughter:[2][3][12]

- Elizabeth Cromwell, who married in 1597 Sir John Shelton of Shelton, Norfolk (21 December 1559 – bef. 1606), and later Thomas Fitzhughes of Oxfordshire.[13]

He married secondly c. 1593 Frances Rugge, (died 30 November 1631), daughter of William Rugge, of Felmingham, Norfolk, and Thomasine Townshend, daughter of Sir Robert Townshend, Justice of Chester, and by her had three children:[2][3]

- Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Ardglass, (11 June 1594 – 1653) married Elizabeth, daughter of Robert Meverell of Throwleigh and Ilam, Staffordshire.[14]

- Frances Cromwell (1595[15] – 25 June 1662), married 30 January 1619 Sir John Wingfield of Tickencote, Rutland.[16] (c. 1595 – 25 December 1631), widower of Jane Turpin, daughter of Sir William Turpin, and High Sheriff of Rutland, and had eight children.

- Anne Cromwell (c. 15 March 1597– 11 July 1636), married Sir Edward Wingfield (died 1638), son of Richard Wingfield of Powerscourt, County Wicklow, and Honora O'Brien. He inherited the estates of his cousin, Richard Wingfield, Viscount Powerscourt, who died without issue in 1634.[17][18] The couple had six sons and a daughter.[19]

Death

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_605292.jpg.webp)

Cromwell died at his home in Downpatrick on 27 April, and was buried in the "ruined chancel" of Down Cathedral, on 24 September 1607. Sir Arthur Chichester, when writing of his death to the council, on 29 September 1607, expressed regret at his loss, "both for his majesty's service and for the poor estate wherein he left his wife and children." He was succeeded by his son, Thomas, as 4th Baron Cromwell, later 1st Viscount Lecale who was created Earl of Ardglass in the Irish peerage on 15 April 1645. The Barony of Cromwell was held by the 1st Viscount Lecale from 22 November 1624 and by the Earls of Ardglass from 15 April 1645 until 26 November 1687, when, on the death of Vere Essex Cromwell, 4th Earl of Ardglass and 7th Baron Cromwell, both titles became extinct.[1][20] His widow, Frances, later married Richard Wingfield, 1st Viscount Powerscourt. She died before 30 November 1631.[1]

Edward Cromwell's son, Thomas visited his father's former manor of Oakham in 1631 where he partook of the ancient tradition of forfeiting a horseshoe in homage to the Lord of the Castle and manor of Oakham. This shoe can be seen on display in the great hall of Oakham Castle today, among others forfeited by Royalty and members of the nobility. Thomas Cromwell died in 1653 and is buried at Tickencote, Rutland. His son Oliver erected a memorial that can be seen in the porch of Down Cathedral today, close to where his grandfather is buried.[8]

References

- Cokayne III 1913, p. 558.

- Grummitt 2008.

- Lee 1888, pp. 151–152.

- Venn 1922, p. 422

- Coningsby 1847, p. 10

- Shaw II 1906, p. 96

- Cecil Papers 11: February 1601, pp. 26–40.

- "Edward Cromwell". Tudorplace.com.ar. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Cecil Papers 11: August 1601, pp. 352–374.

- Cecil Papers 16: Miscellaneous 1604, pp. 393–468.

- Cokayne III 1913, p. 558, His Oakham estate was sold in 1596 to Sir John Harington. Launde was in the possession of Sir William Smith in or before 1603..

- Burke 1831, pp. 152–153.

- Burke 1831, p. 153.

- Cokayne I 1910, pp. 192–193.

- Carthew 1878, p. 525.

- Carthew 1878, pp. 522.

- Burke 2 1833, pp. 316.

- Lodge 1789, p. 272.

- Lodge 1789, p. 272–273.

- "The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle". London: Nichols, Son, and Bentley. 1813. p. 628.

Bibliography

- Burke, John (1831). A General and Heraldic Dictionary of The Peerages of England, Ireland and Scotland, Extinct, Dormant, and in Abeyance. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley.

- Burke, John (1833). A General and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. Vol. 2. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley.

- Carthew, G. A. (1878). The Hundred of Launditch and Deanery of Brisley; in the County of Norfolk; Evidences and Topographical Notes from public records, Heralds' Visitations, Wills, Court Rolls, Old Charters, Parish Registers, Town books, and Other Private Sources; Digested and Arranged as Materials for Parochial, Manorial, and Family History. Vol. II. Collected by G.A. Carthew. Norwich: Printed by Miller and Leavins.

- "Cecil Papers: February 1601, 1-10". Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House. Vol. 11: 1601 (1906). British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "Cecil Papers: August 1601, 21-31". Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House. Vol. 11: 1601 (1906). British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "Cecil Papers: Miscellaneous 1604". Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House. Vol. 16: 1604 (1933). British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- Cokayne, G. E. (1910). Gibbs, Vicary (ed.). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant. Vol. I. London: St. Catherine Press.

- Cokayne, G. E. (1913). Gibbs, Vicary (ed.). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. Vol. III. London: St. Catherine Press.

- Cokayne, G. E. (2000). Gibbs, Vicary; et al. (eds.). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. Vol. I. Gloucester: Alan Sutton Publishing. p. 192.

- Coningsby, Thomas (1847). Nichols, John Gough (ed.). Journal of the Siege of Rouen, 1591. Printed for the Camden Society.

- "Edward Cromwell". Tudorplace.com.ar. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle. Vol. 83. London: Nichols, Son, and Bentley. 1813. p. 628.

- Grummitt, David (January 2008) [First published 2004]. "Cromwell, Edward, Third Baron Cromwell (c.1559–1607)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6763. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lee, Sidney (1888). "Cromwell, Edward". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 151–152.

- Lodge, John; Archdall, Mervyn (1789). The Peerage of Ireland: or, a Genealogical History of the Present Nobility of that Kingdom ... Vol. V. Revised, enlarged, and continued to the present time by Mervyn Archdall, A. M. Dublin: James Moore. p. 272.

- Shaw, W. A.; Burtchaell, G. D. (1906). The Knights of England: A Complete Record from the Earliest Times to the Present Day of the Knights of All the Orders of Chivalry in England, Scotland and Ireland, and of Knights Bachelors. Vol. II. Incorporating a complete list of Knights Bachelors dubbed in Ireland, compiled by G. D. Burtchaell. London: Printed and published for the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, Sherratt and Hughes.

- Venn, John; Venn, J. A. (1922). Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, From the Earliest Times to 1900. Part I: From the Earliest Times to 1751. Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.