Edward Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh

Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, KP, GCVO, FRS (10 November 1847 – 7 October 1927) was an Anglo-Irish businessman and philanthropist. A member of the prominent Guinness family, he was the head of the family's eponymous brewing business, making him the richest man in Ireland. A prominent philanthropist, he is best remembered for his provision of affordable housing in London and Dublin through charitable trusts.

The Earl of Iveagh | |

|---|---|

The 1st Earl of Iveagh | |

| Born | Edward Cecil Guinness 10 November 1847 Clontarf, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 7 October 1927 (aged 79) Grosvenor Place, London, England |

| Resting place | Elveden, Suffolk |

| Education | Trinity College Dublin |

| Political party | Irish Unionist Alliance |

| Spouse | Adelaide Guinness |

| Children | Rupert Guinness, 2nd Earl of Iveagh Ernest Guinness Walter Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne |

| Parent(s) | Benjamin Guinness, 1st Baronet Elizabeth Guinness |

| Family | Guinness |

Public life

Born in Clontarf, Dublin, Guinness was the third son of Sir Benjamin Guinness, 1st Baronet, and younger brother of Arthur Guinness, 1st Baron Ardilaun. Educated at Trinity College Dublin, graduating with BA in 1870, he served as Sheriff of Dublin in 1876, and nine years later became the city's High Sheriff. That same year, he was created a baronet of Castleknock, County Dublin, for helping with the visit of the then Prince of Wales to Ireland. In 1891, Guinness was created Baron Iveagh, of Iveagh in County Down. He was appointed a Knight of St Patrick in 1895, and ten years later was advanced in the Peerage of the United Kingdom to Viscount Iveagh. He was appointed Honorary Colonel of the Dublin City Artillery Militia in 1899.[1] Elected to the Royal Society in 1906, he was two years later elected nineteenth Chancellor of the University of Dublin in 1908–1927, he served as a vice-president of the Royal Dublin Society from 1906 to 1927. In 1910 he was appointed GCVO. In 1919, he was created Earl of Iveagh and Viscount Elveden, of Elveden in the County of Suffolk.[2]

Business

Lord Iveagh was managing director of the Guinness partnership and company, from his father's death in 1868 until 1889, running the largest brewery in the world - it spanned 64 acres (26 ha). He later became chairman of the board for life.

By the age of 29 he had taken over sole ownership of the Dublin brewery after buying out the half-share of his older brother Lord Ardilaun for £600,000 in 1876. Over the next 10 years, Edward Cecil brought unprecedented success to St James's Gate, multiplying the value of his brewery enormously. By 1879 he was brewing 565,000 hogsheads of stout.[3] Seven years later, in 1886, he was selling 635,000 hogsheads in Ireland, 212,000 in Britain, and 60,000 elsewhere, a total of 907,000 hogsheads.[4]

He then became the richest man in Ireland after floating two-thirds of the company in 1886 on the London Stock Exchange for £6 million before retiring a multi-millionaire at the age of 40. He remained chairman of the new public company Guinness, and was its largest shareholder, retaining about 35% of the stock. The amount can be compared to the 1886 GDP of the UK, which was £116 million.[5] By 1914 the brewery's output had doubled again from the 1886 level, to 1,877,000 hogsheads.[6]

In 1902 he commissioned the Guinness Storehouse, that is today one of Ireland's main tourist attractions.

Public housing

Like his father and brother, Lord Iveagh was a generous philanthropist and contributed almost £1 million to slum clearance and housing projects, among other causes. In London this was the 'Guinness Trust', founded in 1890, that manages "over 66,000 homes" in 2020.[7] Most of his aesthetic and philanthropic legacy to Dublin is still intact. The Dublin branch of the Guinness Trust became the Iveagh Trust in 1903, by a private Act of Parliament, which funded the largest area of urban renewal in Edwardian Dublin, and still provides over 10% of the social housing in central Dublin.[8] In 1908 he gave the large back garden of his house at 80 Stephens Green in central Dublin, known as the "Iveagh Gardens", to the new University College Dublin, which is now a public park. Previously he had bought and cleared some slums on the north side of St Patrick's Cathedral and in 1901 he created the public gardens known as "St. Patrick's Park". In nearby Francis Street he built the Iveagh Market to enable street traders to sell produce out of the rain.[9]

Iveagh was portrayed as "Guinness Trust" in a "Spy" cartoon in July 1891.

Medical and scientific research

Iveagh also donated £250,000 to the Lister Institute in 1898, the first medical research charity in the United Kingdom (to be modelled on the Pasteur Institute, studying infectious diseases). In 1908, he co-funded the Radium Institute in London.[10] He also sponsored new physics and botany buildings in Trinity College Dublin in 1903, and part-funded the students' residence at Trinity Hall, Dartry, in 1908.[11]

Iveagh helped finance the British Antarctic Expedition (1907–09) and Mount Iveagh, a mountain in the Supporters Range in Antarctica, is named for him.[12]

Art collector

Interested in fine art all his life, from the 1870s Edward Cecil amassed a distinguished collection of Old Master paintings, antique furniture and historic textiles. In the late 1880s he was a client of Joe Duveen buying screens and furniture; Duveen realised that he was spending much more on fine art at Agnews, and refocused his own business on art sales. He later recalled Edward Cecil as a: "stocky gentleman with a marked Irish brogue".[13]

While he was furnishing his London home at Hyde Park Corner, after he had retired, he began building his art collection in earnest. Much of his collection of paintings was donated to the nation after his death in 1927 and is housed at the Iveagh Bequest at Kenwood, Hampstead, north London. While this lays claim to much of his collection of paintings, it is Farmleigh that best displays his taste in architecture as well as his tastes in antique furniture and textiles. Iveagh was also a patron of then-current artists such as the British portraitist Henry Keyworth Raine[14]

Political life

Iveagh's father had sat as a Conservative MP for Dublin in the 1860s, as did his brother Arthur in the 1870s. Iveagh limited his involvement to acting as High Sheriff of County Dublin in 1885, mindful of the growing movement towards Irish Home Rule in the 1880s and the growth of the electorate under the 1884 Act. He did however stand as a Conservative for the seat of Dublin St Stephen's Green in the 1885 general election, losing to the Irish Parliamentary Party candidate.[15]

Given his wealth he preferred to effect social improvements himself, and preferred a seat in the House of Lords, which he achieved in 1891. He supported the Irish Unionist Alliance. In 1913 he refused to lock out his workforce during the Dublin Lockout. In 1917–18, he took part in the ill-fated Irish Convention that attempted find a moderate solution to the Irish nationalists' demands. Though opposed to Sinn Féin, he had a personal friendship with W. T. Cosgrave who emerged as the first leader of the Irish Free State in 1922.[16]

Like many others in the Irish business world, he had feared that Irish Home Rule would result in new taxes or customs duties between Dublin and Britain, his largest market. The existing free trade within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland would likely turn protectionist, causing a loss of sales, employment and profits. In the event, the new Free State increased the tax on sales within Ireland, but not on exports.

Sporting interests

On land, Iveagh's favourite hobby was to drive a coach-and-four (horses), a very physical activity, occasionally driving from Dublin to the Punchestown Racecourse about 20 miles away, and back. He also was a keen yachtsman, and in 1897 he won a race between England and Kiel that was sponsored by Kaiser Wilhelm. A member of several clubs including the Royal St. George Yacht Club, his main boat was the 204-ton schooner "Cetonia" which he bought in 1880, making frequent appearances at Cowes Week until 1914.[17]

Record estate

After his death in 1927 at Grosvenor Place, London, Iveagh was buried at Elveden, Suffolk. His estate was assessed for probate at £13,486,146 16s. 2d. (roughly equivalent to £856,407,942 in 2021[18]).[19] This remained a British record until the death of Sir John Ellerman in 1933. Although probate was sought in Britain, a part of the death duties was paid to the new Irish Free State. His will bequeathed Kenwood House in Hampstead to the nation as a museum for his art collection, known as the "Iveagh Bequest".[20]

In 1936 his family installed the "Iveagh Window" in his memory, in the north transept of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. The window was designed and made by Sir Frank Brangwyn.[21][22]

In 1939 Iveagh's sons gave his Dublin home at 80 St. Stephen's Green to the Irish Free State, and it was renamed Iveagh House.[23] Since then it has been the home of the Department of Foreign Affairs, and "Iveagh House" has become the metonym of the department.

Family

.png.webp)

In 1873, Iveagh married his third cousin Adelaide Guinness, nicknamed "Dodo". She was descended from the banking line of Guinnesses, and was the daughter of Richard S. Guinness, barrister and MP, and his wife Katherine, a daughter of Sir Charles Jenkinson.

Adelaide's most famous portrait was painted circa 1885 by George Elgar Hicks. They had 3 sons:

- Rupert Guinness, 2nd Earl of Iveagh (1874–1967)

- The Hon. Arthur Ernest Guinness (1876–1949)

- Walter Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne (1880–1944)

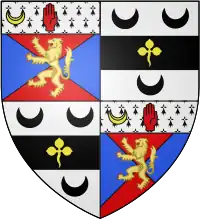

Arms

Earl of Iveagh |

|

See also

References

- Army List.

- London Gazette, No. 31610, p. 12889; 21 October 1919.

- Lynch & Vaizey (1960), op cit, 200–201.

- Wilson & Gourvish, "The Dynamics of the International Brewing Industry Since 1800". Psychology Press, 1998; p. 113.

- "Measuring Worth web site; UK GDP page". Measuringworth.org. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- Wilson & Gourvish, op cit, p. 113 chart.

- https://www.guinnesspartnership.com/about-us/what-we-do/ Guinness partnership, about, 2020.

- See the Dublin Improvement (Bull Alley Area) Act, 1903.

- Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin: The City Within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. Yale: Yale University Press. p. 655. ISBN 0-300-10923-7.

- "Medical research details published in 1927". Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- A short history of giving to Trinity, 2014 booklet by Trinity College Dublin, p. 2.

- "Iveagh, Mount". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Sunday Herald, 30 November 1952, p. 9. Online; accessed 15 September 2014

- Humanities, National Endowment for the (13 May 1906). "The Minneapolis journal. [volume] (Minneapolis, Minn.) 1888-1939, May 13, 1906, Part II, Editorial Section, Image 20". p. 8 – via chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

- Walker, B. M. Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, 1801-1922. Royal Irish Academy. p. 132.

- Joyce, J. The Guinnesses (Poolbeg Press, Dublin 2009), pp. 227–228.

- "The Guinness Fleets | National Maritime Museum of Ireland". Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Iveagh K.P., The Right Honourable Edward Cecil". probatesearchservice.gov. UK Government. 1927. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- 1951 Kenwood guidebook; Bryant J. Kenwood: Paintings in the Iveagh Bequest (2003).

- "The Iveagh Window". Archived from the original on 23 February 2003.

- "Stained-glass Windows". St Patrick's Cathedral. 26 May 2016.

- "1862 – Iveagh House, St. Stephen's Green, Dublin". 19 February 2010.

Bibliography

- G. Martelli, Man of his time (London 1957).

- D. Wilson, Dark and Light (Weidenfeld, London 1998).

- J. Guinness, Requiem for a family business (Macmillan, London 1997).

- S. Dennison and O.MacDonagh, Guinness 1886-1939 From incorporation to the Second World War (Cork University Press 1998).

- F. Aalen, The Iveagh Trust The first hundred years 1890-1990 (Dublin 1990).

- J. Bryant, Kenwood: The Iveagh Bequest (English Heritage publication 2004)

- Joyce, J. The Guinnesses (Poolbeg Press, Dublin 2009)

- Bourke, Edward J. The Guinness Story: The Family, the Business and the Black Stuff (O'Brien Press, 2009). ISBN 978-1-84717-145-0

External links

- Hesilrige, Arthur G. M. (1921). Debrett's Peerage and Titles of courtesy. 160A, Fleet street, London, UK: Dean & Son. p. 507.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Iveagh