Edward Sorin

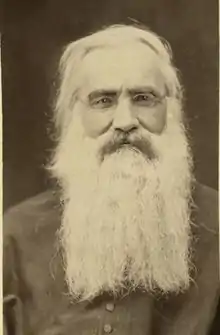

Edward Frederick Sorin, C.S.C. (French: Édouard Sorin;[1] February 6, 1814 – October 31, 1893) was a French-born priest of the Congregation of Holy Cross and the founder of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana and of St. Edward's University in Austin, Texas.

Edward Sorin | |

|---|---|

Édouard Sorin | |

| |

| 1st President of the University of Notre Dame | |

| In office 1844–1865 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Dillon |

| 1st American Provincial Superior of the Congregation of Holy Cross | |

| In office 1865–1868 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Alexis Granger |

| 3rd Superior General of the Congregation of Holy Cross | |

| In office 1868–1893 | |

| Preceded by | Pierre Dufal |

| Succeeded by | Gilbert Français, C.S.C |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 6, 1814 Ahuillé, France |

| Died | October 31, 1893 (aged 79) South Bend, Indiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Holy Cross Cemetery, Notre Dame, Indiana |

| Citizenship | French and American |

| Parents |

|

| Profession | Priest |

| Known for | Founding the University of Notre Dame |

Early life

Edouard Frédéric Sorin was born on February 6, 1814, at in Ahuillé, near Laval, France, to Julian Sorin de la Gaulterie and Marie Anne Louise Gresland de la Margalerie. He was the seventh of nine children, and he was born into a well-off middle-class family and grew up in a three-story manor home (the chateau de la Roche) with seven acres of land. His family was religious and had sheltered two non-juring priests during the persecutions of the French Revolution. He received an early education in the home, in the local village school, and by the local parish priest.[2] He then enrolled in the School of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in Laval, but after one year he decided to become a priest and with his family's backing enrolled at the diocesan seminary in Precigné. Here he completed his humanities course and then enrolled at the major seminary in Le Mans for theology. Among his fellow students was the future cardinals Benoît-Marie Langénieux and Guillame Meignan.[3] Here he made the acquaintance of Basil Moreau, who was vice rector and professor of scripture. He also became interested in missionary work after listening to the pleads of Simon Bruté, bishop of Vicennes in Indiana, who had returned to France to recruit missionaries.[2]

Completing his seminary studies, he was ordained a priest on May 27, 1838, and was assigned as parish priest in Parcé-sur-Sarthe.[4] He remained in this position for about fourteen month, but then desired to join Basil Moreau's novel organization, the Congregation of Holy Cross (born out of the merger of Moreau's auxiliary priests and Jacques-Francois Dujarié's Brothers of Saint Joseph). With the bishop's permission, he joined the group and underwent a brief novitiate. On August 15, 1840, Sorin - together with Basil Moreau and three other priests - were the first members of the Congregation of Holy Cross to take solemn vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.[2]

Missionary to America

Simon Bruté, who Sorin has witnessed recruiting priests and missionaries for his recently established diocese in Vincennes in Indiana, died in 1839. His successor Célestin Guynemer de la Hailandière renewed the call for help, and Moreau decided to send assistance. Because of Sorin's leadership abilities, motivation, and youthful vigor, Moreau chose him to lead this missionary expedition.[5][2] Missionary enterprise in foreign lands, including distant lands such as China, Japan or America, motivated French clergy and inspired numerous vocations.[3] Sorin was accompanied by six brothers of the Congregation: Brothers Vincent (born John Pieau), Joachim (William Michael André), Lawrence (John Menage), Francis Xavier (René Patois), Anselm (Pierre Caillot), and Gratian (Urban Mosimer).[2]

Founding of the University of Notre Dame

Journey to America and time in St Peter's

Accompanied by the six brothers, Sorin left Le Mans on August 5, 1841, and left Le Havre on board the ship Iowa. They arrived in New York City on September 13, and one of Sorin's first acts upon arrival to America was to kneel down and kiss the ground, as a sign of adoption of his new country. They spent three days in the city hosted by Samuel Byerley, a rich trader and convert to Catholicism, and met with New York's bishop John Dubois. On September 16 they went up the Hudson River by paddleboat to Albany and then reached Buffalo via the Erie Canal, with a short detour to view Niagara falls. They crossed Lake Erie on steamboat and reached Toledo, from where they went down to Maumee river to Maumee, then Napoleon, Defiance, Fort Wayne, Lafayette, Terre Haute, and following the Wabash river they finally reached Vincennes on October 10.[2]

Bishop Célestine Hailandière welcomed the congregation and first offered them property and ministry in Francesville, but Sorin declined. He accepted the bishop's second offer of establishing themselves in the parish of St. Peter in Montgomery. The mission already had a few buildings, a small wooden chapel, and a primitive school with a few pupils. The school was soon headed by Charles Rother, a German immigrant who soon desired to join the congregation and became the first to do so in the United States, with the name of Brother Joseph. Other brothers soon joined, mostly Irish and German immigrants, although many left. The start of the mission saw some hardships, particularly in adopting foreign agricultural practices and the cultivation of corn, but they adapted with help from the locals. Sorin celebrated Mass and gave spiritual assistance to around thirty-five Catholic families in the area, preaching in French and sometimes English, a language Sorin was only beginning to learn.[2][3]

Soon, more problems developed in the community.[2] Sorin and bishop Hailandière had disagreements over financial matters, since Sorin expected the bishop to provide 3,000 francs for their expenses. The bishop, who had expected them in 1839, had already employed the money elsewhere. Despite this, the bishop agreed to pay for the community, but on the condition they would report to him instead of being under the jurisdiction of Moreau, a condition which Sorin refused. This disagreement was partially diffused by Father Juliane Delaune, who was able to solicit funds and donations amounting to 15,000 francs, which he divided between Sorin and the bishop. A second and deeper misunderstanding arose when Sorin made his intentions to start a collège (a college-high school on the French model). The bishop rejected this idea, since there already was a Catholic college in Vincennes, St Gabriel's, which was staffed by the Erudists fathers. The bishop had promised them he would have no competition for funds and students.[3] Instead, the bishop mentioned that he owned land in northern Indiana, close to South Bend, and Sorin could start his college there instead.[4] This land had been purchased by Stephen Badin in the 1830s with the intent of building a school, but after his plans had failed he offered it to the bishop. Sorin consulted with the brothers and then accepted, departing St. Peter's with seven of the brothers on November 16.[2]

Founding of Notre Dame

Sorin and his seven brothers (three French and four Irish) traveled 250 miles north in one of Indiana's harshest winters. They followed the Wabash River, passing by Terre Haute. They split, and Sorin with the first group arrived in South Bend on the afternoon of November 26, 1842.[6][7] Here they were welcomed by Alexis Coquillard (who bishop Hailandière had put them in contact with) and then undertook the two-mile trip to visit the property before spending the night guests of Coquillard. The next day they visited the site with day-light, and took formal possession of the property.[8] Rev. Sorin described his arrival on campus in a letter to Basil Moreau:

Everything was frozen, and yet it all appeared so beautiful. The lake, particularly, with its mantle of snow, resplendent in its whiteness, was to us a symbol of the stainless purity of Our August Lady, whose name it bears; and also of the purity of soul which should characterize the new inhabitants of these beautiful shores. Our lodgings appeared to us-as indeed they are-but little different from those at St. Peter's. We made haste to inspect all the various sites on the banks of the lake which had been so highly praised. Yes, like little children, in spite of the cold, we went from one extremity to the other, perfectly enchanted with the marvelous beauties of our new abode. Oh! may this new Eden be ever the home of innocence and virtue!

At the time, the property only had three buildings: a log cabin built by Stephen Badin (the original burned down in 1856 but a replica was built in 1906), a small two-story clapboard building that was the home of the Potawatomi interpreter Charon, and a small shed. Of the 524 acres, only 10 were cleared and ready for cultivation, but Sorin stated that the soil was suitable for raising wheat and corn. While the land had two small lakes, the snow and marshy area might have given to Sorin the appearance of a single larger lake, hence why named the fledgling mission "Notre Dame du Lac" (Our Lady of the Lake).[10][8] The most immediate concern were suitable and warm lodgings for the Sorin and the seven brothers present and for those in St. Peter's who were yet to come north.[8] To build a second log cabin, and lacking the funds, they appealed to the people of South Bend to donate funds or their time. Thanks to the help from the locals, they were able to assemble the timber and erect the walls, and the Sorin and the brothers erected the roof when the men returned to town. The cabin was completed on March 19, 1843, in time to accommodate the additional brothers and novices who has arrived from St. Peter's the month before.[10]

Next, Sorin dedicated himself to building a college proper, since the foundation of such within two years was the condition on which he had been given the land by bishop Hailandière. While in Vincennes, Sorin had made plans with a local architect, Mr. Marsile, to have him come to South Bend in the summer and start construction of a main building, but the architect did not show up. Hence, he and the brothers constructed Old College, a two-story brick building that served as dormitory, bakery, and classrooms. With the Old College building ready by the fall, the college officially opened to its first few students.[2] The first residents to receive an education at Notre Dame were orphans from a home established by the Brothers of Saint Joseph to educate children beyond the ages of 12 and 13.[11] When Marsile finally arrived in August, Sorin proceeded to erect the first Main Building (at the location of the third and present Main Building). The building, completed in 1844 and enlarged in 1853, constituted the entire college until the construction of the second and larger Main Building in 1865.[12]

Following Moreau's example, Sorin sent out priests and brothers to found other schools and parishes throughout the United States and Canada. On January 15, 1844, the Indiana legislature officially chartered the University of Notre Dame.[13]

From the French seminary system, Sorin was by temperament more of an administrator than an academic or intellectual.[14] He ran Notre Dame on the model of a French boarding school, which included elementary (the "minims"), preparatory, and collegiate programs, as well as a manual training school. Over the years, he accepted the recommendations of others, including Fr. John A. Zahm, C.S.C., to strengthen Notre Dame's academic curriculum.[15]

In 1850 Sorin asked the federal government to establish a post office at Notre Dame. His request was granted, and in 1851 First Assistant Postmaster General Fitz Henry Warren notified congressman Graham N. Fitch of the establishment of the Notre Dame post office and the appointment of Edward Sorin as its postmaster. While the income from the post office was negligible, its major advantage was to increase the visibility of Notre Dame and incentivize better roads and communications to the campus.[17]

In 1865 he became the first American Provincial Superior of the Congregation and was succeeded as president by Patrick Dillon. As provincial superior, he was still actively involved with the running of the university and resided on campus.

Provincial Superior of the Congregation

Far from Indiana to India, the flourishing mission in Eastern Bengal, headed by the Congregation of Holy Cross, owes much of its success to Father Sorin's active co-operation and zeal. He sent its former bishop and other priests together with a band of sisters, described as a worthy group. The founding of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Cross in the United States is regarded as one of Sorin's most important services to religion. Under his administration and care, this community grew from small to possessing flourishing establishments in a dozen states. During the American Civil War, under Sorin's forethought, this sisterhood was able to furnish nearly eighty nurses for sick and wounded soldiers on transports and in hospitals. A number of priests of the Congregation of Holy Cross, among them Fr. William Corby, C.S.C., served as chaplains at the front. Sorin also established Ave Maria Press in 1865.[5]

1879 fire of the Main Building

Sorin's strength was demonstrated on April 23, 1879, when a fire destroyed the Main Building, which housed virtually the entire university.[18] Following the pledge made by the university's president, William Corby, C.S.C., Notre Dame reopened for the fall term.[19] Sorin also willed Notre Dame to rebuild and continue its growth. As recounted in Notre Dame: 100 Years (1942):

"The sixty-five year old man walked around the ruins, and those who followed him were confounded by his attitude. Instead of bending, he stiffened. There was on his face a look of grim determination. He signaled all of them to go into the church with him." [20]

Timothy Edward Howard provided a first-person account of what Sorin said inside Sacred Heart Church:

"I was then present when Father Sorin, after looking over the destruction of his life-work, stood at the altar steps of the only building left and spoke to the community what I have always felt to be the most sublime words I ever listened to. There was absolute faith, confidence, resolution in his very look and pose. 'If it were ALL gone, I should not give up!' were his words in closing. The effect was electric. It was the crowning moment of his life. A sad company had gone into the church that day. They were all simple Christian heroes as they came out. There was never more a shadow of a doubt as to the future of Notre Dame."[20]

An alternative version of Sorin's post-fire address has increased in popularity. It argues that Our Lady (the Virgin Mary) burned down the Main Building because he built it too small, and that he would now rebuild it "bigger and better than ever".[21] This version seems apocryphal as it was not included in any contemporaneous accounts of the event or in Sorin's own writings. Sorin believed a divine hand was involved in the fire's origins, but ascribed it directly to God, whom Sorin suspected of being angry over "infidelity" and "neglect," not the dimensions of the building.[22]

Sorin had an ambitious goal for the new Administration Building, constructed over the summer of 1879. He wanted it to be nothing less than a "monument to Catholicism."[23] Having stood for some 135 years, the Administration Building with its Golden Dome served as a monument. Catholicism generally and millions of working-class first- and second-generation American Catholics were inspired to see their sons (and eventually daughters) pursue higher education. It allowed them to gain entry into the mainstream of American social, economic, and political life.

Superior General

Sorin was elected superior-general of his order in 1868, and held this office for the rest of his life. During his tenure as Superior General, Fr. Sorin made around 50 voyages across the Atlantic to deal with the affairs of the Congregation in France and Rome. In order to ease the debt of the Congregation and put on more solid financial footing, he oversaw the sale of the church of Notre Dame de Sainte Croix, its boarding school, and the rest of the Congregation property in Le Mans, which until then had served as the order's headquarters.[24] Hence the headquarters was moved to Notre Dame, Indiana. Sorin was invited to attend the Provincial Council of Cincinnati of 1882 and the Plenary Council of American Bishops at Baltimore in 1884.[2]

Founding of St. Edward's University

Sorin also founded St. Edward's University in Austin, Texas. Bishop Claude Marie Dubuis of the Diocese of Galveston learned of Mrs. Mary Doyle's intention to leave her large South Austin farm to the Catholic Church. The purpose was to establish an "education institution" and he invited Father Sorin to Texas in 1872. Answering the bishop's invitation, Sorin traveled to Austin and surveyed the beauty of the surrounding hills and lakes. A year later, following Mrs. Doyle's death, he founded a Catholic school called St. Edward's Academy in honor of his patron saint, Edward the Confessor and King. In the fledgling institution's first year, 1878, three farm boys made up the student body and met for classes in a makeshift building on the old Doyle homestead. In 1885, the academy secured its charter as a college. Sorin Hall and nearby Sorin Oak — the largest oak tree in Austin — are also named after him.[25]

Personal life

While Sorin was attached to his French roots, he had a deep desire to be an American and his attachment to his new country manifested in several ways.[2] Notre Dame's first end of year celebration in 1845 was opened by a reading of the Declaration of Independence. He became an American citizen in 1850, and was soon after that named to the government positions of local postmaster and superintendent of the roads. One of the earliest buildings on the Notre Dame campus, Washington Hall, was named after the first U.S. president rather than a Catholic saint.[2] During the Civil War, he allowed several priests and eighty sisters of the community to volunteer as chaplains and nurses, despite their absence affecting the university. His thorough "Americanism" and his "American patriotism and [his] love of American institutions" were praised by John Ireland.[26]

In recognition of his work in education, the French Government conferred upon him the insignia of Officer of Public Instruction in 1888.

Final years

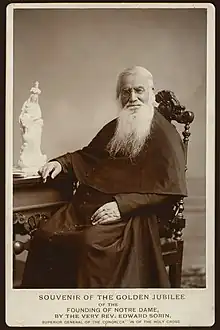

A Golden Jubilee in 1888 marked the fiftieth anniversary of Sorin's priestly ordination, which had taken place in 1838. One first celebration occurred during the school year, with the student present, on the actual anniversary of the ordination. On May 26 all campus building were decorated with flags and banners. The entertainment consisted in a reception with students, faculty, and administration, followed by speeches, poems, recitals, and musical performances. After dinner, Sorin and the faculty members gathered on the Main Building porch and watched the Notre Dame Band perform in the quad and the student military units give their gun salutes. The student, faculty and alumni gifted Sorin with a barouche drawn by two black horses. The night was marked by fireworks, paper lanterns, and further celebrations.[27] On May 27, the anniversary of the ordination, Sorin celebrated a Solemn High Mass with William Corby delivering the sermon. Afterwards, Sorin blessed the cornerstone of a new residence hall, which Sorin discovered was to be named Sorin Hall in his honor. This was followed by further celebrations, while baseball games and boat races were deferred to the next day due to rain.[28]

While this first celebration was reserved for the campus community, second one, of a more official and public nature, was held a few month later on August 15, 1888. General invitations in newspapers across the country via the Associated Press. Thousands of people came to Notre Dame for the event, and many more sent their congratulation to Sorin by letters and telegrams. The most high-profile attendee was Cardinal James Gibbons, then the most significant prelate in the American Catholic Church. A huge crowd gathered at the train station in South Bend to witness his arrival on August 14. William Corby took Gibbons in Sorin's barouche from the station to Notre Damem, and their procession was greeted with bands of music, the toil of the bells of Notre Dame, and plenty decorations and illuminations. The local chapter of the Ancient Order of Hibernians acted as escort.[29] The jubilee was also attended by other high-profile members of the church, such as two archbishops (William H. Elder of Cincinnati and John Ireland of St. Paul) and twelve bishops (Richard Gilmour of Cleveland, Joseph Dwenger of Fort Wayne, John Watterson of Columbus, Richard Phelan of Pittsburgh, James Ryan of Alton, John Janssen of Belleville, John Keane of Washington, D.C., Maurice Burke of Cheyenne, John Lancaster Spalding of Peoria, Stephen V. Ryan of Buffalo, and Henry J. Richter of Grand Rapids).[28] The events of August 15 started with the consecration of Sacred Heart Church, led by bishop Dwenger, followed by the blessing of the large bell by bishop Burke. A High Mass was celebrated by Cardinal Gibbons, with a sermon by Archbishop Ireland and a choir from Chicago that sang Joseph Haydn's Imperial Mass.[29] This was followed by a lavish banquet in the Main Building refectories.[28]

Sorin's golden jubilee was the climax of a long history of expansion and success for the Congregation and the university, and for the Catholic Church in America as whole. O'Connel writes that "What had been accomplished at Notre Dame under [Sorin's] stewardship seemed to a wider public emblematic of the growth and maturing of the American Catholic Church as a whole, an there were those in high places anxious to give expression to this fact. To honor the founder of Notre Dame was in effect to proclaim the enduring and legitimate status of the Church, after much struggle, had attained within American society. In accord, therefore, with the late nineteenth century's predilection for gaudy celebrations, featuring bands and banquets, fireworks and fiery oratory, plans were formulated at the beginning of 1888 to solemnize Father Sorin's golden anniversary as a national as well as personal triumph."[30]

Soon after the celebration of his golden jubilee, Sorin entered into a long period of mental and physical suffering.[5] He died a peaceful and painless death of Bright's Disease at the University of Notre Dame on the eve of All Saints' Day, October 31, 1893. The funeral, which was attended by a large crowd, was celebrate on November 11 in the Church of the Sacred Heart and Archbishop William Henry Elder gave the funeral homily.[31] He was buried in the Holy Cross Cemetery, as is tradition for all members of the Congregation.

Legacy

Several memorials have been dedicated to Rev. Sorin on the campus of the University of Notre Dame. A staue of Edward F. Sorin, on the intersection of the main and south quads, is one of the main landmarks on the Notre Dame Campus.[32][33] Sorin Hall was dedicated to Sorin in 1888, with Sorin himself present.[34][35] Sorin Court, a street behind Main Building, and Sorin's, the restaurant inside the Morris Inn, are also named after him.[36] Several other programs on campus, such as the Sorin Fellows and the Sorin Scholars, are named in his honor.[37][38] The city of South Bend has dedicated Sorin Street and Sorin Park in his honor, and Sorin Street in Austin is also named after him.[36][39] Sorinsville was an Irish immigrant neighborhood in South Bend that developed in the 19th and 20th centuries.[40] On the campus of St. Edward's University, Sorin Hall and the Sorin Oak, the largest oak tree in Austin, are named after him.[25]

Both the University of Notre Dame and St. Edward's University celebrate Founder's Day in his honor.[41][42] At the Notre Dame, Founder's Day started being celebrated almost immediately in the early 1840s. By Sorin's own request, the celebrations took place on October 13, feast of his patron saint St. Edward, instead of Sorin's birthday. Students from both Notre Dame and Saint Mary's celebrated with theatrical and musical performances, fireworks, athletic events, a feast in the dining halls, and by sending cards and well wishes to Sorin.[42][43] Over the years, the magnitude of the festivity waned, and by the 1960s a wreath was lay at the bottom of Sorin's statue, and in recent times it is commemorated simply with a special Mass in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart.[44] In 2014, Notre Dame launched a year-long celebration to commemorate the Bicentennial of the birth of Sorin. The celebration was kicked-off with a Mass while the dining hall served a special French cuisine feast. During the year, the University Archives launched a major effort to digitize Sorin's papers, the Hesburgh library hosted a Sorin Exhibit in the main concourse, and several lectures about Sorin were held.[45][46]

Works

- Sorin, Edward (1882). The minims of Notre Dame: a serio-comic drama. Notre Dame, Ind.: OCLC 18713760.

- Sorin, Edward (1883). The angel of the schools: a manual of devotion for the use of Catholic youth. New York: Sadlier. OCLC 22369619.

- Sorin, Edward (1879). Bells at Notre Dame. Notre Dame, Ind.: OCLC 953978788.

- Sorin, Edward (1885). Circular letters of the Very Rev. Edward Sorin, Superior general of the Congregation of the Holy Cross and founder of Notre Dame. Notre Dame, Ind. OCLC 4275356.

- Sorin, Edward (2001). Chronicles of Notre Dame du Lac. James T. Connelly, John M. Toohey. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-02270-4. OCLC 50094714.

References

- "Édouard Sorin", in Alphonse-Victor Angot et Ferdinand Gaugain, Dictionnaire historique, topographique et biographique de la Mayenne, Laval, Goupil, 1900-1910, t. III, p. 719.

- Blantz, Thomas E. (2020). The University of Notre Dame : a history. [Notre Dame, Indiana]. ISBN 978-0-268-10824-3. OCLC 1182853710.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Archives of the University of Notre Dame: Sketch of Father Edward Sorin's Life". Archives.nd.edu. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "Edward Frederick Sorin | American educator". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Hudson, Daniel."Edward Sorin." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 20 February 2020PD-notice}}

- O'Connell, Marvin R. (2001). Edward Sorin. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-02759-5. OCLC 46884132.

- Hope, Arthur J. (1978). Notre Dame, one hundred years. South Bend, Ind.: Icarus Press. ISBN 0-89651-500-1. OCLC 4494082.

- Sorin, Edward (2001). Chronicles of Notre Dame du Lac. James T. Connelly, John M. Toohey. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-02270-4. OCLC 50094714.

- "Letter to Father General Moreau" (PDF). archives.nd.edu. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- Schlereth, Thomas J. (1976). The University of Notre Dame : a portrait of its history and campus. Notre Dame, Indiana. ISBN 0-268-01905-3. OCLC 1974264.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C. // de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture // University of Notre Dame". ethicscenter.nd.edu. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- Archives, Notre Dame (February 6, 2014). "Edward Sorin & the Founding of Notre Dame". Notre Dame Archives News & Notes. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- "University of Notre Dame". Holycrossusa.org. March 24, 2014. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- Marvin O'Connell, Edward Sorin, pp. 564, 626

- M. O'Connell, supra, pp. 564, 627.

- "Romancing the Golden Dome - Chicago Tribune". Archived from the original on April 10, 2013.

- Archives, Notre Dame (July 7, 2011). "Notre Dame Post Offices". Notre Dame Archives News & Notes. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- "The Great Fire of 1879 | Notre Dame Archives News & Notes". Archives.nd.edu. April 23, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- M. O'Connell, supra, p. 651

- Hope, C.S.C., Arthur C."Notre Dame -- One Hundred Years"|date=May 7, 2012

- Dame, University Communications | University of Notre. "History". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Who can take it [the fire], at first sight, for anything else but a punishment? ... We all hope it will prove a salutary punishment of something that has displeased God but a punishment is meant; to see anything else in our catastrophe could hardly be sustained by any process of reasoning." url=http://www.archives.nd.edu/circulars/CLO1-1879-05-01.pdf |format=PDF |title=Circular Letter No. 96 |date=May 1, 1879 |publisher=Archives.nd.edu.

- "By all means we must bring upon these new foundations the richest blessings of Heaven, that the grand edifice we contemplate erecting may remain for ages to come a monument to Catholicism, and a stronghold which no destructive element can ever shake on its basis or bring down again from its majestic stand. Circular Letter No. 96, supra.

- "Edward Frederick SORIN". Sanctuaire Basile Moreau. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- "Sorin Oak - St. Edward's - PocketSights". pocketsights.com. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- "Sermon Delivered on the Occasion of the Sacerdotal Golden Jubilee of Very Rev. E. Sorin, CSC" (PDF). Scholastic. XXII (1): 7. August 25, 1888.

- Scholastic, February 6, 1888, page 595

- Archives, Notre Dame (August 15, 2013). "Sorin's Golden Jubilee". Notre Dame Archives News & Notes. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Scholastic, August 25, 1888

- O'Connell, page 702]

- "Fr. Sorin dies // Notre Dame 175 // University of Notre Dame". Notre Dame 175. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- Notre Dame Scholastic (1906). "Father Sorin" (PDF). Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- "Edward F. Sorin, (sculpture)". Smithsonian American Art Museum (2016). Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "Sorin Hall dorm // Notre Dame 175 // University of Notre Dame". Notre Dame 175. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Archives, Notre Dame (January 9, 2013). "The Traveling Father Sorin Statue". Notre Dame Archives News & Notes. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "Behind the Name: An indomitable personality". South Bend Tribune. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "Sorin Fellows Program // de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture // University of Notre Dame". ethicscenter.nd.edu. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "Sorin Scholars // Flatley Center for Undergraduate Scholarly Engagement // University of Notre Dame". Flatley Center for Undergraduate Scholarly Engagement. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "Mueller Street Legends | About | Mueller Austin". www.muelleraustin.com. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Rotman, Deborah L. (June 1, 2010). "The Fighting Irish: Historical Archaeology of Nineteenth-Century Catholic Immigrant Experiences in South Bend, Indiana". Historical Archaeology. 44 (2): 113–131. doi:10.1007/BF03376797. ISSN 2328-1103. S2CID 160302370.

- "Father Sorin | St. Edward's University in Austin, Texas". www.stedwards.edu. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Archives, Notre Dame (October 13, 2010). "Founder's Day". Notre Dame Archives News & Notes. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "FOUNDER's DAY AT NOTRE DAME". The Inter Ocean. October 14, 1897. p. 10. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Dame, Marketing Communications: Web // University of Notre (October 12, 2009). "Celebrating Founder's Day". Notre Dame News. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "Notre Dame launches year-long commemoration of Fr. Sorin's bicentennial // The Observer". The Observer. February 13, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- "Cushwa Center Lecture - Dean John McGreevy // Events // Sorin Bicentennial // University of Notre Dame". sorin200.nd.edu. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Edward Sorin". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Edward Sorin". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Bibliography

- Connelly, J. T. (2020). The History of the Congregation of Holy Cross. United States: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-10887-0

- Klawitter, G. (2016). Early Men of Holy Cross: “To Sustain Each Other Until Death”. United States: iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-5320-0966-2

- Lemarié, Charles (1978). Le Père Édouard Sorin: 1814-1893, fondateur de l'Université Notre-Dame-du-Lac, Indiana, États-Unis (in French). Angers (place André Leroy, 49005, cedex): Université catholique de l'Ouest. OCLC 7280708.

- O'Connell, Marvin R (2001). Edward Sorin. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-02759-5. OCLC 46884132.

- Sorin, Edward (1992). Chronicles of Notre Dame du Lac. James T. Connelly, John M. Toohey. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-02270-4. OCLC 50094714.