Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton

Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton, PC (4 April 1883 – 26 August 1962), styled Viscount Turnour until 1907, was an Irish peer and British politician who served as a Member of Parliament for 47 years, attaining the rare distinction of serving as both Baby of the House and Father of the House at the opposite ends of his career in the House of Commons.

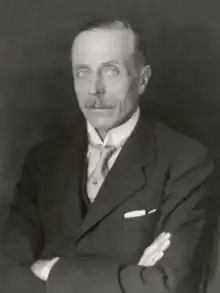

The Earl Winterton | |

|---|---|

Turnour in 1936 | |

| Father of the House of Commons | |

| In office 13 February 1945 – 25 October 1951 | |

| Preceded by | David Lloyd George |

| Succeeded by | Hugh O'Neill |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

| In office 28 May 1937 – 29 January 1939 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Sir J. C. C. Davidson |

| Succeeded by | William Morrison |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord temporal | |

| In office 1952 – 26 August 1962 | |

| Member of Parliament for Horsham Horsham & Worthing (1918–1945) | |

| In office 11 November 1904 – 4 October 1951 | |

| Preceded by | Heywood Johnstone |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Gough |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 April 1883 |

| Died | 26 August 1962 (aged 79) |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse | Hon. Cecilia Monica Wilson |

| Parent(s) | Edward Turnour, 5th Earl Winterton Lady Georgiana Susan Hamilton |

Background

Turnour was the son of Edward Turnour, 5th Earl Winterton, and Lady Georgiana Susan Hamilton (1841–1913), daughter of James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Abercorn.

Turnour was educated at Eton College.[1]

Political career

Turnour was first elected for Horsham in a by-election in 1904 at the age of just 21, the youngest Member of Parliament (MP) in the Commons, and remained an MP for the next 47 years. In 1907 he succeeded his father, becoming 6th Earl Winterton. This was an Irish peerage and did not disqualify him from remaining a member of the House of Commons. Sitting as a Conservative, Winterton slowly rose through the ranks, later achieving ministerial office as Under-Secretary of State for India in 1922, a post he held until 1924. In 1924 he was sworn of the Privy Council and once again served as Under-Secretary of State for India from 1924 to 1929.

Winterton did not hold office in the National Governments headed by firstly Ramsay MacDonald and then Stanley Baldwin. However, when Neville Chamberlain became Prime Minister in May 1937, Winterton was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. In March 1938 he was promoted to the Cabinet and given the job of speaking in the House of Commons on behalf of the Secretary of State for Air Viscount Swinton, a member of the House of Lords. In this role he proved a noted failure, especially in a heated debate in May 1938 which led to Chamberlain concluding that the Secretary of State for Air must be an MP. In July 1938 he led the British delegation to the Evian Conference at which the problem of the Jewish refugees was debated. Thereafter, Winterton was increasingly sidelined. The following year he was dropped from the Cabinet and served in the marginal post of Paymaster General before leaving the government altogether.

Winterton remained a Member of Parliament until 1951, by which time he was the MP with the longest continuous service. In 1952 he was created Baron Turnour, of Shillinglee in the County of Sussex, in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, which gave him a seat in the House of Lords. The Patent creating this peerage is currently in the possession of Mark Lindley-Highfield of Ballumbie Castle.

Personal life

In September 1910 the mother of Ivy Gordon-Lennox acted to contradict a rumour that her daughter was engaged to marry Winterton, going so far as to place a notice in The New York Times to say that there was no engagement.[2] Winterton married the Honourable Cecilia Monica Wilson, daughter of Charles Wilson, 2nd Baron Nunburnholme, in 1924. The marriage was childless. Winterton died in August 1962, aged 79, when the barony of Turnour became extinct. He was succeeded in his Irish titles by his kinsman, Ronald Chard Turnour, 7th Earl Winterton.

References

- Hansard, Fifth Series, Volume 175, Col., 930, 25 March 1952

- Ivy Gordon-Lennox Not Engaged dated 25 September 1910, at nytimes.com, accessed 24 July 2008

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl Winterton

- Newspaper clippings about Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

_(2022).svg.png.webp)