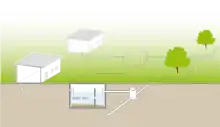

Effluent sewer

Effluent sewer systems, also called septic tank effluent gravity (STEG), solids-free sewer (SFS), or septic tank effluent drainage (STED) systems, have septic tanks that collect sewage from residences and businesses, and the liquid fraction of sewage that comes out of the tank is conveyed to a downstream receiving body such as either a centralized sewage treatment plant or a distributed treatment system for further treatment or disposal away from the community generating the sewage. Most of the solids are removed by the interceptor tanks, so the treatment plant can be much smaller than a typical plant and any pumping for the supernatant can be simpler without grinders (sometimes water pumps are sufficient).

An alternative effluent sewer which is similar to the STEG system is the STEP system. Because of the vast reduction of solid wastes and the capture of fats, oils and grease (FOG) within the interceptor tank, a pumping system can be used to move the wastewater under pressure rather than a gravity driven conveyance system.

Design considerations

Effluent pumping sewers have small diameter pipes that follow the contour of the land and are only buried a metre or two underground. While an effluent sewer can use gravity to move waste, the ability to move waste with a pressure system can be a big advantage in places where a gravity system is impractical. Compared to conventional sewer systems, effluent sewer systems can be installed at a shallow depth and do not require a minimum wastewater flow or slope to function.[1]

Effluent sewer systems, as well as all sewer systems, can use two methods to transport wastewater to a treatment facility. These methods are gravity and pumping, also called pressure systems. Gravity systems use pipes that are laid on a slight downhill slope to transport wastewater. Effluent pumping systems have pipes that are buried at a constant depth, such as a metre and a half, and rely on pumping stations that create pressure to move the waste to a treatment facility. An effluent sewer that uses gravity may be called a septic tank effluent gravity (STEG) system, while a pumping system may be called a septic tank effluent pumping (STEP) system. It is also possible to have a hybrid system that uses gravity and pumping. Gravity and pumping effluent sewer systems both have advantages and disadvantages. The best type of system to use depends on the area it will be serving. Factors such as population size, topography, groundwater level, as well as locations for pumping stations and the treatment plant, must be taken into account. STEG systems should not be confused with traditional sewer systems that use gravity to transport untreated sewage to a wastewater treatment plant, which are typically referred to as gravity sewer systems.

Comparison with other systems

Conventional gravity sewers

Effluent sewer systems are a much less common sewage disposal method than gravity sewer systems that use gravity, as well as pumping where needed, to send raw sewage and other wastewater straight from consumers to a sewage treatment plant. There are two main types of gravity sewers, sanitary and combined. Sanitary sewers only treat the wastewater from homes and business. Combined sewers have storm drains that are connected to the sewerage. In areas with high rainfall, this results in an enormous additional amount of wastewater that has to be treated. Combined sewers have higher operating costs due to the larger volume of wastewater that has to be treated, and they may require larger treatment plants, as well. In addition, when it rains very hard, the treatment plant will not be able to keep up, which can result in untreated wastewater being dumped into the plant's outfall, which may be a river, lake or ocean. When this occurs, the operator of the sewer is usually fined by one or more of the government bodies that oversee the body of water that the wastewater was dumped into. To prevent this, some cities have tanks, pits or ponds to store the excess wastewater until it can be properly treated. To prevent groundwater contamination, the pits and ponds should have liners if sewage has already been combined with the storm runoff.

Septic tanks

Effluent sewers also currently serve fewer people than septic systems, which also use septic tanks, but simply dispose of the effluent by draining it into a leach field. About one quarter of United States homes dispose of their wastewater with septic tanks. However, effluent sewers are being looked at as a sewage treatment solution in areas where gravity sewer systems are not well-suited or when the high capital cost to build a gravity system is prohibitive. Areas that are less than ideal for gravity systems include areas that are large, but extremely flat and areas that require long-distance pumping, such as where homes are widely spread out or when several small villages or towns connect their sewage systems so that a centralized plant can be built.

Another problem area is a place where there are many homes or businesses at or near the lowest elevation in the area, such as sea level for a coastal city. Typically, waste is pumped uphill under low pressure to the main sewer line in such situations, either after it has been through a septic tank or after it has been ground up into a slurry by a grinder. Grinding can be done when the waste of many homes or businesses is combined or smaller grinders can be installed at each home or business. A disadvantage of using grinders is that they require electricity, and a disadvantage of using septic tanks is that they require solid waste buildup to be removed every one to three years, depending on the size of the tank and the number of people using the system.

Septic tanks also have a higher capital cost if they are being installed for new homes or if the existing septic tanks must be replaced. If there is a suitable septic tank in place, pumping the effluent from the tank is the lowest cost option for initial costs. Whether the septic tank is the lowest cost option over time depends on the cost of electricity in the area, how often the tank must be emptied and how much it costs to have the solids pumped out of the tank.

See also

References

- Tilley, E.; Ulrich, L.; Lüthi, C.; Reymond, Ph.; Zurbrügg, C. (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies - (2nd Revised ed.). Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), Duebendorf, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-906484-57-0.