El Lahun

El Lahun (Arabic: اللاهون El Lāhūn, Coptic: ⲗⲉϩⲱⲛⲉ alt. Illahun, Lahun, or Kahun (the latter being a neologism coined by archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie) is a workmen's village in Faiyum, Egypt. El Lahun is associated with the Pyramid of Senusret II (Greek: Sesostris II), which is located near the modern town, and is often called the Pyramid of Lahun. The ancient name of the site was rꜣ-ḥn.t, literally, "Mouth (or Opening) of the Canal"). It was known as Ptolemais Hormos (Ancient Greek: Πτολεμαῒς ὅρμος, romanized: port of Ptolemy) in Ptolemaic Egypt.[1]

El Lahun

اللاهون ⲗⲉϩⲱⲛⲉ | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Pyramid of Senusret II at Lahun | |

El Lahun Location in Egypt | |

| Coordinates: 29°14′N 30°58′E | |

| Country | Egypt |

| City | Faiyum |

Overview

Like the other Twelfth Dynasty pyramids in the Faiyum, the Pyramid of Lahun is made of mudbrick, but here the core of the pyramid consists of a network of stone walls that were infilled by mudbrick. This approach was probably intended to ensure the stability of the brick structure. Unusually, despite a Pyramid Temple on the east side, the entrance to the pyramid is on the south. The archaeologist Flinders Petrie nevertheless spent considerable time searching for it on the east side. He discovered the entrance only when workmen clearing the nearby tombs of the nobles discovered a small tunnel at the bottom of a 40-foot shaft, which led to the royal burial chamber. Evidently the original workmen on the tomb had used their legitimate activity as a cover for digging this tunnel, which enabled them to rob the pyramid. Once he was in the burial chamber, Petrie was able to work backwards to the entrance.

The pyramid stands on an artificial terrace cut from sloping ground. On the north side eight rectangular blocks of stone were left to serve as mastabas, probably for the burial of personages associated with the royal court. In front of each mastaba is a narrow shaft leading down to the burial chamber underneath. Also on the north side is the Queen's Pyramid or subsidiary pyramid.

The most remarkable discovery was that of the village of the workers who both constructed the pyramid and then served the funerary cult of the king. The village, conventionally known as Kahun, is about 800 meters from the pyramid and lies in the desert a short distance from the edge of cultivation. When found, many of the buildings were extant up to roof height, and Petrie confirmed that the true arch was known and used by the workmen in the village. However, all the buildings found were demolished in the process of excavation, which proceeded in long strips down the length of the village. When the first strip had been cleared, mapped and drawn, the next strip was excavated and the spoil dumped in the previous strip. As a result, there is very little to be seen on the site today. The main function "has usually been linked to the funerary cult of Senwosret II [ie. Senusret II] – whose nearby pyramid complex has been understood as the main reason for its existence – housing administrators, as well as temple staff for the upkeep of his royal mortuary cult."[2]

The village was excavated by Petrie in 1888–90 and again in 1914. The excavation was remarkable for the number, range, and quality of objects of everyday life (including tools) that were found in the houses. According to Dr Rosalie David's Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt, "the quantity, range and type of articles of everyday use which were left behind in the houses may indeed suggest that the departure [of the workmen] was sudden and unpremeditated" (p. 199). Among the curiosities found there were wooden boxes buried beneath the floors of many of the houses. When opened they were found to contain the skeletons of infants, sometimes two or three in a box, and aged only a few months at death. Petrie reburied these human remains in the desert.

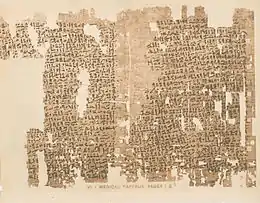

Also found in the town were the Kahun papyri, comprising about 1000 fragments, covering legal and medical matters. Re-excavation of the area in 2009 by Egyptian archaeologists revealed a cache of pharaonic-era mummies in brightly painted wooden coffins in the sand-covered desert rock surrounding the pyramid.[3]

The site was occupied into the late Thirteenth Dynasty, and then again in the New Kingdom, when there were large land reclamation schemes in the area.

Town layout

The town was laid out in a regular plan, with mudbrick town walls on three sides. No evidence was found of a fourth wall, which may have collapsed and been washed away during the annual inundation. The town was rectangular in shape and was divided internally by a mudbrick wall as large and strong as the exterior walls. This wall divided about one third of the area of the town and in this smaller area the houses consisted of rows of back-to-back, side-by-side single room houses. The larger area, which was higher up the slope and thus benefited from whatever breeze was blowing, contained a much smaller number of large, multi-room villas. The size of the houses ranged from 2,520 square meters for the elite houses to 120 square meters for small houses.[4] Petrie compared the village to a Welsh mining village, where the workers lived in terraces in the valley while the mine owner and overseers lived in larger houses up the hill.

A major feature of the town was the so-called "acropolis" building. This was an important building, as indicated by the presence of column bases. Petrie suggested that this may have been the King’s residence whilst he was visiting construction work. The building seems to have been out of use and derelict before the end of occupation.

Other records show that there were a large number of Semitic slaves in Egypt during the Twelfth Dynasty.[5] It is interesting that some of the villas were constructed of layers of mudbrick separated by layers of reed matting, a technique used in Mesopotamia. Furthermore, burial beneath the living quarters of a house was a custom noted at Ur by Woolley. It is possible that the workers who were so carefully guarded by the village wall and separated from the overseers by an equally strong wall were Semitic (Asiatic) slaves not trusted by their overseers.

Discoveries

It was announced by the Supreme Council of Antiquities on 26 April 2009 that an anthology of pharaonic-era mummies in vividly painted wooden coffins were uncovered near the Lahun pyramid in Egypt. The sarcophagi were decorated with bright hues of green, red and white bearing images of their occupants. Archaeologists unearthed dozens of mummies, thirty of which were very well preserved with prayers purposed to help the deceased in the afterlife inscribed upon them. The site, once enveloped in slabs of white limestone, revealed that it could possibly be thousands of years older than previously thought.[6]

Experts think that a new understanding of Egyptian funerary architecture and customs of the Middle Kingdom all the way to the Roman era could be learned from the exploration of the dozens of tombs encompassing the site near the Lahun, Egypt’s southernmost pyramid. "The tombs were cut on the rock itself, and they vary in architectural designs," said archaeologist Abdel Rahman El-Aydi, head of excavations at the site. Some of the tombs were erected on top of gravesites from earlier eras. Ayedi told reporters: "The prevailing idea was that this site has been established by Senusret II, the fourth king of the 12th Dynasty. But in light of our discovery, I think we are going to change this theory, and soon we will announce another discovery." He said that teams had made a discovery of an artefact that was dated earlier than the 12th Dynasty, but did not include any specifics on the item and promised an official statement would be made within days.[7]

Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities announced on 23 May 2010 that 57 ancient Egyptian tombs were discovered in an area close to Lahun. Most of the graves contained an ornamental painted wooden sarcophagus with a mummy inside. Some of the tombs date to the Egyptian First and Second dynasties, as far back as 2750 BC.[8] Several of the sites were decorated with hieroglyphics that the ancients believed would help the deceased travel through the afterlife.[9]

Twelve of the tombs were found to belong to the Eighteenth Dynasty, which ruled Egypt during the second millennium BC. Egyptologist Zahi Hawass said the mummies that date to the 18th Dynasty are covered in linen decorated with religious texts from the Book of the Dead and scenes of ancient Egyptian deities. The discovery might help experts have a better understanding of the ancient Egyptian religions. Some of the tombs are decorated with religious texts that ancient Egyptians believed would help the deceased cross over to the underworld, said Abdel Rahman El-Aydi, chief archaeologist of project.[10] El-Aydi said one of the oldest tombs is almost completely intact, with all of its funerary equipment and a wooden sarcophagus containing a mummy wrapped in linen.[11]

In 31 of the tombs, dating back to around 2030–1840 B.C., during the Middle Kingdom era, archaeologists found scenes of different ancient Egyptian deities such as Horus, Amun, Hathor, and Khnum decorated on the tombs.[12]

%252C_Faiyum%252C_Egypt._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%252C_London.jpg.webp) Spouted jar, brown smooth pottery. From a box containing infant burial, with a lock of hair, shell, slip of wood, and beads. 12th Dynasty. From Lahun (Kahun), Faiyum, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Spouted jar, brown smooth pottery. From a box containing infant burial, with a lock of hair, shell, slip of wood, and beads. 12th Dynasty. From Lahun (Kahun), Faiyum, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Dried date, peach, apricot, and stones. From Lahun, Fayum, Egypt. Late Middle Kingdom. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Dried date, peach, apricot, and stones. From Lahun, Fayum, Egypt. Late Middle Kingdom. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London A bag of white linen, unopened. Contains rolls of linen only. Foundation deposit, Heb Sed Chapel at Lahun, Fayum, Egypt. 12th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

A bag of white linen, unopened. Contains rolls of linen only. Foundation deposit, Heb Sed Chapel at Lahun, Fayum, Egypt. 12th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian sites, including sites of temples

Bibliography

- G. Brunton: Lahun I: The Treasure (BSAE 27 en ERA 20 (1914)), London 1920.

- A.R. David: The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt: A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh’s Workforce, London, Boston en Henley 1986.

- B. Gunn: The Name of the Pyramid-Town of Sesostris II, in JEA 31 (1945), p. 106-107.

- B. J. Kemp: Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization, London 1989.

- W.M.F. Petrie, G. Brunton, M. A. Murray: Lahun II (BSAE 33 en ERA 26 (1920)), London 1923.

- W.M.F. Petrie, F. Ll. Griffith, P.E. Newberry: Kahun, Gurob, and Hawara, London 1890.

- W.M.F. Petrie: Illahun, Kahun, and Gurob, London 1891.

- S. Quirke: (ed.), Lahun Studies, New Malden 1998.

- S. Quirke: Lahun: A Town in Egypt 1800 BC, and the History of Its Landscape, London 2005.

- A. Scharff: Illahun und die mit Königsnamen des Mittleren Reiches gebildeten Ortsnamen, in ZÄS 59 (1924), p. 51-55.

- K. Szpakowska: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt: Recreating Lahun, Malden, Oxford, Carlton 2008 ISBN 978-1-4051-1856-9

- H. E. Winlock: The Treasure of el Lahun, New York 1973.

References

- Peust, Carsten. "Die Toponyme vorarabischen Ursprungs im modernen Ägypten" (PDF). p. 57.

- Nadine Moeller, The Foundation and Purpose of the Settlement at Lahun during the Middle Kingdom: A New Evaluation in R.K. Ritner (ed.), Essays for the Library of Seshat. Studies Presented to Janet H. Johnson on the occasion of her 70th birthday, SOAC 70, Chicago: The Oriental Institute, (2018), p.183.

- Johnson, C. Cache of mummies unearthed at Egypt's Lahun pyramid. April 26, 2009.

- "A Planned Town of the Middle Kingdom: Kahun." Arts and Humanities Through the Eras. Gale. 2005. Archived 2016-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "on stelae and in papyri Asiatic slaves are increasingly often mentioned, though there is no means of telling whether they were prisoners of war or had infiltrated into Egypt of their own accord." Gardiner, "Egypt of the Pharaohs", Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966, p. 133

- redOrbit (2009-04-27). "New Cache Of Mummies Discovered In Egypt - Redorbit". Redorbit. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- redOrbit (2009-04-27). "New Cache Of Mummies Discovered In Egypt - Redorbit". Redorbit. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- "Ancient Egyptian Tomb Revealed". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 2018-11-25. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- Archived 2020-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 2020-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 2020-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 2020-10-22 at the Wayback Machine