Promethium

Promethium is a chemical element with the symbol Pm and atomic number 61. All of its isotopes are radioactive; it is extremely rare, with only about 500–600 grams naturally occurring in Earth's crust at any given time. Promethium is one of only two radioactive elements that are followed in the periodic table by elements with stable forms, the other being technetium. Chemically, promethium is a lanthanide. Promethium shows only one stable oxidation state of +3.

| Promethium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /proʊˈmiːθiəm/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | metallic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [145] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Promethium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 61 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | f-block groups (no number) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | f-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f5 6s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 23, 8, 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1315 K (1042 °C, 1908 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3273 K (3000 °C, 5432 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 7.26 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 7.13 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 289 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +2, +3 (a mildly basic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.13 (?) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 183 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 199 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | from decay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

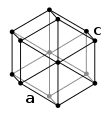

| Crystal structure | double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 9.0 µm/(m⋅K)[1] (at r.t.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 17.9 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | est. 0.75 µΩ⋅m (at r.t.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | α form: est. 46 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | α form: est. 18 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | α form: est. 33 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | α form: est. 0.28 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-12-2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

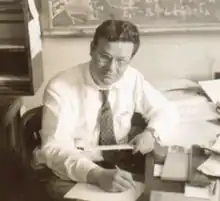

| Discovery | Charles D. Coryell, Jacob A. Marinsky, Lawrence E. Glendenin (1945) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Grace Mary Coryell (1945) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of promethium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1902 Bohuslav Brauner suggested that there was a then-unknown element with properties intermediate between those of the known elements neodymium (60) and samarium (62); this was confirmed in 1914 by Henry Moseley, who, having measured the atomic numbers of all the elements then known, found that atomic number 61 was missing. In 1926, two groups (one Italian and one American) claimed to have isolated a sample of element 61; both "discoveries" were soon proven to be false. In 1938, during a nuclear experiment conducted at Ohio State University, a few radioactive nuclides were produced that certainly were not radioisotopes of neodymium or samarium, but there was a lack of chemical proof that element 61 was produced, and the discovery was not generally recognized. Promethium was first produced and characterized at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 1945 by the separation and analysis of the fission products of uranium fuel irradiated in a graphite reactor. The discoverers proposed the name "prometheum" (the spelling was subsequently changed), derived from Prometheus, the Titan in Greek mythology who stole fire from Mount Olympus and brought it down to humans, to symbolize "both the daring and the possible misuse of mankind's intellect". However, a sample of the metal was made only in 1963.

The two sources of natural promethium are rare alpha decays of natural europium-151 (producing promethium-147) and spontaneous fission of uranium (various isotopes). Promethium-145 is the most stable promethium isotope, but the only isotope with practical applications is promethium-147, chemical compounds of which are used in luminous paint, atomic batteries and thickness-measurement devices. Because natural promethium is exceedingly scarce, it is typically synthesized by bombarding uranium-235 (enriched uranium) with thermal neutrons to produce promethium-147 as a fission product.

Properties

Physical properties

A promethium atom has 61 electrons, arranged in the configuration [Xe] 4f5 6s2. The seven 4f and 6s electrons are valence.[4] In forming compounds, the atom loses its two outermost electrons and one of the 4f-electrons, which belongs to an open subshell. The element's atomic radius is the second largest among all the lanthanides but is only slightly greater than those of the neighboring elements.[4] It is the most notable exception to the general trend of the contraction of lanthanide atoms with the increase of their atomic numbers (see lanthanide contraction[5]). Many properties of promethium rely on its position among lanthanides and are intermediate between those of neodymium and samarium. For example, the melting point, the first three ionization energies, and the hydration energy are greater than those of neodymium and lower than those of samarium;[4] similarly, the estimate for the boiling point, ionic (Pm3+) radius, and standard heat of formation of monatomic gas are greater than those of samarium and less than those of neodymium.[4]

Promethium has a double hexagonal close packed (dhcp) structure and a hardness of 63 kg/mm2.[6] This low-temperature alpha form converts into a beta, body-centered cubic (bcc) phase upon heating to 890 °C.[7]

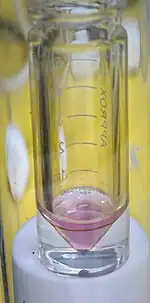

Chemical properties and compounds

Promethium belongs to the cerium group of lanthanides and is chemically very similar to the neighboring elements.[8] Because of its instability, chemical studies of promethium are incomplete. Even though a few compounds have been synthesized, they are not fully studied; in general, they tend to be pink or red in color.[9][10] Treatment of acidic solutions containing Pm3+ ions with ammonia results in a gelatinous light-brown sediment of hydroxide, Pm(OH)3, which is insoluble in water.[11] When dissolved in hydrochloric acid, a water-soluble yellow salt, PmCl3, is produced;[11] similarly, when dissolved in nitric acid, a nitrate results, Pm(NO3)3. The latter is also well-soluble; when dried, it forms pink crystals, similar to Nd(NO3)3.[11] The electron configuration for Pm3+ is [Xe] 4f4, and the color of the ion is pink. The ground state term symbol is 5I4.[12] The sulfate is slightly soluble, like the other cerium group sulfates. Cell parameters have been calculated for its octahydrate; they lead to conclusion that the density of Pm2(SO4)3·8H2O is 2.86 g/cm3.[13] The oxalate, Pm2(C2O4)3·10H2O, has the lowest solubility of all lanthanide oxalates.[14]

Unlike the nitrate, the oxide is similar to the corresponding samarium salt and not the neodymium salt. As-synthesized, e.g. by heating the oxalate, it is a white or lavender-colored powder with disordered structure.[11] This powder crystallizes in a cubic lattice upon heating to 600 °C. Further annealing at 800 °C and then at 1750 °C irreversibly transforms it to monoclinic and hexagonal phases, respectively, and the last two phases can be interconverted by adjusting the annealing time and temperature.[15]

| Formula | symmetry | space group | No | Pearson symbol | a (pm) | b (pm) | c (pm) | Z | density, g/cm3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Pm | dhcp[6][7] | P63/mmc | 194 | hP4 | 365 | 365 | 1165 | 4 | 7.26 |

| β-Pm | bcc[7] | Fm3m | 225 | cF4 | 410 | 410 | 410 | 4 | 6.99 |

| Pm2O3 | cubic[15] | Ia3 | 206 | cI80 | 1099 | 1099 | 1099 | 16 | 6.77 |

| Pm2O3 | monoclinic[15] | C2/m | 12 | mS30 | 1422 | 365 | 891 | 6 | 7.40 |

| Pm2O3 | hexagonal[15] | P3m1 | 164 | hP5 | 380.2 | 380.2 | 595.4 | 1 | 7.53 |

Promethium forms only one stable oxidation state, +3, in the form of ions; this is in line with other lanthanides. According to its position in the periodic table, the element cannot be expected to form stable +4 or +2 oxidation states; treating chemical compounds containing Pm3+ ions with strong oxidizing or reducing agents showed that the ion is not easily oxidized or reduced.[8]

| Formula | color | coordination number |

symmetry | space group | No | Pearson symbol | m.p. (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PmF3 | Purple-pink | 11 | hexagonal | P3c1 | 165 | hP24 | 1338 |

| PmCl3 | Lavender | 9 | hexagonal | P63/mc | 176 | hP8 | 655 |

| PmBr3 | Red | 8 | orthorhombic | Cmcm | 63 | oS16 | 624 |

| α-PmI3 | Red | 8 | orthorhombic | Cmcm | 63 | oS16 | α→β |

| β-PmI3 | Red | 6 | rhombohedral | R3 | 148 | hR24 | 695 |

Isotopes

Promethium is the only lanthanide and one of only two elements among the first 82 that has no stable or long-lived (primordial) isotopes. This is a result of a rarely occurring effect of the liquid drop model and stabilities of neighbor element isotopes; it is also the least stable element of the first 84.[3] The primary decay products are neodymium and samarium isotopes (promethium-146 decays to both, the lighter isotopes generally to neodymium via positron decay and electron capture, and the heavier isotopes to samarium via beta decay). Promethium nuclear isomers may decay to other promethium isotopes and one isotope (145Pm) has a very rare alpha decay mode to stable praseodymium-141.[3]

The most stable isotope of the element is promethium-145, which has a specific activity of 940 Ci/g (35 TBq/g) and a half-life of 17.7 years via electron capture.[3][17] Because it has 84 neutrons (two more than 82, which is a magic number which corresponds to a stable neutron configuration), it may emit an alpha particle (which has 2 neutrons) to form praseodymium-141 with 82 neutrons. Thus it is the only promethium isotope with an experimentally observed alpha decay.[18] Its partial half-life for alpha decay is about 6.3×109 years, and the relative probability for a 145Pm nucleus to decay in this way is 2.8×10−7 %. Several other promethium isotopes such as 144Pm, 146Pm, and 147Pm also have a positive energy release for alpha decay; their alpha decays are predicted to occur but have not been observed. In total, 41 isotopes of promethium are known, ranging from 126Pm to 166Pm.[3][19]

The element also has 18 nuclear isomers, with mass numbers of 133 to 142, 144, 148, 149, 152, and 154 (some mass numbers have more than one isomer). The most stable of them is promethium-148m, with a half-life of 43.1 days; this is longer than the half-lives of the ground states of all promethium isotopes, except for promethium-143 to 147. In fact, promethium-148m has a longer half-life than its ground state, promethium-148.[3]

Occurrence

In 1934, Willard Libby reported that he had found weak beta activity in pure neodymium, which was attributed to a half-life over 1012 years.[20] Almost 20 years later, it was claimed that the element occurs in natural neodymium in equilibrium in quantities below 10−20 grams of promethium per one gram of neodymium.[20] However, these observations were disproved by newer investigations, because for all seven naturally occurring neodymium isotopes, any single beta decays (which can produce promethium isotopes) are forbidden by energy conservation.[21] In particular, careful measurements of atomic masses show that the mass difference between 150Nd and 150Pm is negative (−87 keV), which absolutely prevents the single beta decay of 150Nd to 150Pm.[22]

In 1965, Olavi Erämetsä separated out traces of 147Pm from a rare earth concentrate purified from apatite, resulting in an upper limit of 10−21 for the abundance of promethium in nature; this may have been produced by the natural nuclear fission of uranium, or by cosmic ray spallation of 146Nd.[23]

Both isotopes of natural europium have larger mass excesses than sums of those of their potential alpha daughters plus that of an alpha particle; therefore, they (stable in practice) may alpha decay to promethium.[24] Research at Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso showed that europium-151 decays to promethium-147 with the half-life of 5×1018 years.[24] It has been shown that europium is "responsible" for about 12 grams of promethium in the Earth's crust.[24] Alpha decays for europium-153 have not been found yet, and its theoretically calculated half-life is so high (due to low energy of decay) that this process will probably not be observed in the near future.

Promethium can also be formed in nature as a product of spontaneous fission of uranium-238.[20] Only trace amounts can be found in naturally occurring ores: a sample of pitchblende has been found to contain promethium at a concentration of four parts per quintillion (4×10−18) by mass.[25] Uranium is thus "responsible" for 560 g of promethium in Earth's crust.[24]

Promethium has also been identified in the spectrum of the star HR 465 in Andromeda; it also has been found in HD 101065 (Przybylski's star) and HD 965.[26] Because of the short half-life of promethium isotopes, they should be formed near the surface of those stars.[17]

History

Searches for element 61

In 1902, Czech chemist Bohuslav Brauner found out that the differences in properties between neodymium and samarium were the largest between any two consecutive lanthanides in the sequence then known; as a conclusion, he suggested there was an element with intermediate properties between them.[27] This prediction was supported in 1914 by Henry Moseley who, having discovered that atomic number was an experimentally measurable property of elements, found that a few atomic numbers had no known corresponding elements: the gaps were 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, and 87.[28] With the knowledge of a gap in the periodic table several groups started to search for the predicted element among other rare earths in the natural environment.[29][30][31]

The first claim of a discovery was published by Luigi Rolla and Lorenzo Fernandes of Florence, Italy. After separating a mixture of a few rare earth elements nitrate concentrate from the Brazilian mineral monazite by fractionated crystallization, they yielded a solution containing mostly samarium. This solution gave x-ray spectra attributed to samarium and element 61. In honor of their city, they named element 61 "florentium". The results were published in 1926, but the scientists claimed that the experiments were done in 1924.[32][33][34][35][36][37] Also in 1926, a group of scientists from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Smith Hopkins and Len Yntema published the discovery of element 61. They named it "illinium", after the university.[38][39][40] Both of these reported discoveries were shown to be erroneous because the spectrum line that "corresponded" to element 61 was identical to that of didymium; the lines thought to belong to element 61 turned out to belong to a few impurities (barium, chromium, and platinum).[29]

In 1934, Josef Mattauch finally formulated the isobar rule. One of the indirect consequences of this rule was that element 61 was unable to form stable isotopes.[29][41] From 1938, a nuclear experiment was conducted by H. B. Law et al. at the Ohio State University. Nuclides were produced in 1941 which were not radioisotopes of neodymium or samarium, and the name "cyclonium" was proposed, but there was a lack of chemical proof that element 61 was produced and the discovery not largely recognized.[42][43]

Discovery and synthesis of promethium metal

Promethium was first produced and characterized at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Clinton Laboratories at that time) in 1945 by Jacob A. Marinsky, Lawrence E. Glendenin and Charles D. Coryell by separation and analysis of the fission products of uranium fuel irradiated in the graphite reactor; however, being too busy with military-related research during World War II, they did not announce their discovery until 1947.[44][45] The original proposed name was "clintonium", after the laboratory where the work was conducted; however, the name "prometheum" was suggested by Grace Mary Coryell, the wife of one of the discoverers.[42] It is derived from Prometheus, the Titan in Greek mythology who stole fire from Mount Olympus and brought it down to humans[42] and symbolizes "both the daring and the possible misuse of the mankind intellect".[46] The spelling was then changed to "promethium", as this was in accordance with most other metals.[42]

In 1963, promethium(III) fluoride was used to make promethium metal. Provisionally purified from impurities of samarium, neodymium, and americium, it was put into a tantalum crucible which was located in another tantalum crucible; the outer crucible contained lithium metal (10 times excess compared to promethium).[9][14] After creating a vacuum, the chemicals were mixed to produce promethium metal:

- PmF3 + 3 Li → Pm + 3 LiF

The promethium sample produced was used to measure a few of the metal's properties, such as its melting point.[14]

In 1963, ion-exchange methods were used at ORNL to prepare about ten grams of promethium from nuclear reactor fuel processing wastes.[17][47][48]

Promethium can be either recovered from the byproducts of uranium fission or produced by bombarding 146Nd with neutrons, turning it into 147Nd which decays into 147Pm through beta decay with a half-life of 11 days.[49]

Production

The production methods for different isotopes vary, and only those for promethium-147 are given because it is the only isotope with industrial applications. Promethium-147 is produced in large quantities (compared to other isotopes) by bombarding uranium-235 with thermal neutrons. The output is relatively high, at 2.6% of the total product.[50] Another way to produce promethium-147 is via neodymium-147, which decays to promethium-147 with a short half-life. Neodymium-147 can be obtained either by bombarding enriched neodymium-146 with thermal neutrons[51] or by bombarding a uranium carbide target with energetic protons in a particle accelerator.[52] Another method is to bombard uranium-238 with fast neutrons to cause fast fission, which, among multiple reaction products, creates promethium-147.[53]

As early as the 1960s, Oak Ridge National Laboratory could produce 650 grams of promethium per year[54] and was the world's only large-volume synthesis facility.[55] Gram-scale production of promethium has been discontinued in the U.S. in the early 1980s, but will possibly be resumed after 2010 at the High Flux Isotope Reactor. In 2010, Russia was the only country producing promethium-147 on a relatively large scale.[51]

Applications

Most promethium is used only for research purposes, except for promethium-147, which can be found outside laboratories.[42] It is obtained as the oxide or chloride,[56] in milligram quantities.[42] This isotope does not emit gamma rays, and its radiation has a relatively small penetration depth in matter and a relatively long half-life.[56]

Some signal lights use a luminous paint, containing a phosphor that absorbs the beta radiation emitted by promethium-147 and emits light.[17][42] This isotope does not cause aging of the phosphor, as alpha emitters do,[56] and therefore the light emission is stable for a few years.[56] Originally, radium-226 was used for the purpose, but it was later replaced by promethium-147 and tritium (hydrogen-3).[57] Promethium may be favored over tritium for nuclear safety reasons.[58]

In atomic batteries, the beta particles emitted by promethium-147 are converted into electric current by sandwiching a small promethium source between two semiconductor plates. These batteries have a useful lifetime of about five years.[10][17][42] The first promethium-based battery was assembled in 1964 and generated "a few milliwatts of power from a volume of about 2 cubic inches, including shielding".[59]

Promethium is also used to measure the thickness of materials by evaluating the amount of radiation from a promethium source that passes through the sample.[17][9][60] It has possible future uses in portable X-ray sources, and as auxiliary heat or power sources for space probes and satellites[61] (although the alpha emitter plutonium-238 has become standard for most space-exploration-related uses).[62]

Promethium-147 is also used, albeit in very small quantities (less than 330nCi), in some Philips CFL (Compact Fluorescent Lamp) glow switches in the PLC 22W/28W 15mm CFL range.[63]

Precautions

The element has no biological role. Promethium-147 can emit gamma rays during its beta decay,[64] which are dangerous for all lifeforms. Interactions with tiny quantities of promethium-147 are not hazardous if certain precautions are observed.[65] In general, gloves, footwear covers, safety glasses, and an outer layer of easily removed protective clothing should be used.[66]

It is not known what human organs are affected by interaction with promethium; a possible candidate is the bone tissues.[66] Sealed promethium-147 is not dangerous. However, if the packaging is damaged, then promethium becomes dangerous to the environment and humans. If radioactive contamination is found, the contaminated area should be washed with water and soap, but, even though promethium mainly affects the skin, the skin should not be abraded. If a promethium leak is found, the area should be identified as hazardous and evacuated, and emergency services must be contacted. No dangers from promethium aside from the radioactivity are known.[66]

References

- Cverna, Fran (2002). "Ch. 2 Thermal Expansion". ASM Ready Reference: Thermal properties of metals (PDF). ASM International. ISBN 978-0-87170-768-0.

- Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1233. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey (1988), Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, pp. 776, 955, ISBN 0-471-84997-9

- Pallmer, P. G.; Chikalla, T. D. (1971). "The crystal structure of promethium". Journal of the Less Common Metals. 24 (3): 233. doi:10.1016/0022-5088(71)90101-9.

- Gschneidner Jr., K.A. (2005). "Physical Properties of the rare earth metals" (PDF). In Lide, D. R. (ed.). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0486-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-18. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 120.

- Emsley 2011, p. 429.

- promethium. Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 121.

- Aspinall, H. C. (2001). Chemistry of the f-block elements. Gordon & Breach. p. 34, Table 2.1. ISBN 978-9056993337.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 122.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 123.

- Chikalla, T. D.; McNeilly, C. E.; Roberts, F. P. (1972). "Polymorphic Modifications of Pm2O3". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 55 (8): 428. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1972.tb11329.x.

- Cotton, Simon (2006). Lanthanide And Actinide Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-470-01006-8.

- Hammond, C. R. (2011). "Prometium in "The Elements"". In Haynes, William M. (ed.). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 4.28. ISBN 978-1439855119.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 114.

- Kiss, G. G.; Vitéz-Sveiczer, A.; Saito, Y.; et al. (2022). "Measuring the β-decay properties of neutron-rich exotic Pm, Sm, Eu, and Gd isotopes to constrain the nucleosynthesis yields in the rare-earth region". The Astrophysical Journal. 936 (107): 107. Bibcode:2022ApJ...936..107K. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac80fc. hdl:2117/375253. S2CID 252108123.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 117.

- G. Audi; A. H. Wapstra; C. Thibault; J. Blachot; O. Bersillon (2003). "The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties" (PDF). Nuclear Physics A. 729 (1): 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.8504. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-23.

- N. E. Holden (2004). "Table of the Isotopes". In D. R. Lide (ed.). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85th ed.). CRC Press. Section 11. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- McGill, Ian. "Rare Earth Elements". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Vol. 31. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 188. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_607.

- Belli, P.; Bernabei, R.; Cappella, F.; et al. (2007). "Search for α decay of natural Europium". Nuclear Physics A. 789 (1–4): 15–29. Bibcode:2007NuPhA.789...15B. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2007.03.001.

- Attrep, Moses Jr. & Kuroda, P. K. (May 1968). "Promethium in pitchblende". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 30 (3): 699–703. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(68)80427-0.

- C. R. Cowley; W. P. Bidelman; S. Hubrig; G. Mathys & D. J. Bord (2004). "On the possible presence of promethium in the spectra of HD 101065 (Przybylski's star) and HD 965". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 419 (3): 1087–1093. Bibcode:2004A&A...419.1087C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20035726.

- Laing, Michael (2005). "A Revised Periodic Table: With the Lanthanides Repositioned". Foundations of Chemistry. 7 (3): 203–233. doi:10.1007/s10698-004-5959-9. S2CID 97792365.

- Littlefield, Thomas Albert; Thorley, Norman (1968). Atomic and Nuclear Physics: An Introduction in S.I. Units (2nd ed.). Van Nostrand. p. 109.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 108.

- Weeks, Mary Elvira (1956). The discovery of the elements (6th ed.). Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education.

- Marshall, James L. Marshall; Marshall, Virginia R. Marshall (2016). "Rediscovery of the elements: The Rare Earths–The Last Member" (PDF). The Hexagon: 4–9. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Rolla, Luigi; Fernandes, Lorenzo (1926). "Über das Element der Atomnummer 61". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie (in German). 157: 371–381. doi:10.1002/zaac.19261570129.

- Noyes, W. A. (1927). "Florentium or Illinium?". Nature. 120 (3009): 14. Bibcode:1927Natur.120...14N. doi:10.1038/120014c0. S2CID 4094131.

- Rolla, L.; Fernandes, L. (1927). "Florentium or Illinium?". Nature. 119 (3000): 637. Bibcode:1927Natur.119..637R. doi:10.1038/119637a0. S2CID 4127574.

- Rolla, Luigi; Fernandes, Lorenzo (1928). "Florentium. II". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 169: 319–320. doi:10.1002/zaac.19281690128.

- Rolla, Luigi; Fernandes, Lorenzo (1927). "Florentium". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 163: 40–42. doi:10.1002/zaac.19271630104.

- Rolla, Luigi; Fernandes, Lorenzo (1927). "Über Das Element der Atomnummer 61 (Florentium)". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 160: 190–192. doi:10.1002/zaac.19271600119.

- Harris, J. A.; Yntema, L. F.; Hopkins, B. S. (1926). "The Element of Atomic Number 61; Illinium". Nature. 117 (2953): 792. Bibcode:1926Natur.117..792H. doi:10.1038/117792a0.

- Brauner, Bohuslav (1926). "The New Element of Atomic Number 61: Illinium". Nature. 118 (2959): 84–85. Bibcode:1926Natur.118...84B. doi:10.1038/118084b0. S2CID 4089909.

- Meyer, R. J.; Schumacher, G.; Kotowski, A. (1926). "Über das Element 61 (Illinium)". Naturwissenschaften. 14 (33): 771. Bibcode:1926NW.....14..771M. doi:10.1007/BF01490264. S2CID 46235121.

- Thyssen, Pieter; Binnemans, Koen (2011). "Accommodation of the Rare Earths in the Periodic Table: A Historical Analysis". In Gschneider, Karl A. Jr.; Bünzli, Jean-Claude; Pecharsky, Vitalij K. (eds.). Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-444-53590-0. OCLC 690920513. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- Emsley 2011, p. 428.

- Fontani, Marco; Costa, Mariagrazia; Orna, Mary Virginia (2015) [2014]. The Lost Elements [The Periodic Table's Shadow Side]. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 302–303. ISBN 978-0-19-938334-4.

- Marinsky, J. A.; Glendenin, L. E.; Coryell, C. D. (1947). "The chemical identification of radioisotopes of neodymium and of element 61". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 69 (11): 2781–5. doi:10.1021/ja01203a059. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086506477. PMID 20270831.

- "Discovery of Promethium". Oak Ridge National Laboratory Review. 36 (1). 2003. Archived from the original on 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

"Discovery of Promethium" (PDF). Oak Ridge National Laboratory Review. 36 (1): 3. 2003. Retrieved 2018-06-17. - Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils; Holleman, Arnold Frederick (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons. p. 1694. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- Lee, Chung-Sin; Wang, Yun-Ming; Cheng, Wu-Long; Ting, Gann (1989). "Chemical study on the separation and purification of promethium-147". Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 130: 21–37. doi:10.1007/BF02037697. S2CID 96599441.

- Orr, P. B. (1962). "Ion exchange purification of promethium-147 and its separation from americium-241, with diethylenetriaminepenta-acetic acid as the eluant" (PDF). Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

Orr, P. B. (1962). "Ion exchange purification of promethium-147 and its separation from americium-241, with diethylenetriaminepenta-acetic acid as the eluant". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. doi:10.2172/4819080. hdl:2027/mdp.39015077313933. OSTI 4819080. Retrieved 2018-06-17.{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Gagnon, Steve. "The Element Promethium". Jefferson Lab. Science Education. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 115.

- Duggirala, Rajesh; Lal, Amit; Radhakrishnan, Shankar (2010). Radioisotope Thin-Film Powered Microsystems. Springer. p. 12. ISBN 978-1441967626.

- Hänninen, Pekka; Härmä, Harri (2011). Applications of inorganic mass spectrometry. Springer. p. 144. ISBN 978-3-642-21022-8.

- De Laeter; J. R. (2001). Applications of inorganic mass spectrometry. Wiley-IEEE. p. 205. ISBN 978-0471345398.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 116.

- Gerber, Michele Stenehjem; Findlay, John M. (2007). On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford Nuclear Site (3rd ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8032-5995-9.

- Lavrukhina & Pozdnyakov 1966, p. 118.

- Tykva, Richard; Berg, Dieter (2004). Man-made and natural radioactivity in environmental pollution and radiochronology. Springer. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4020-1860-2.

- Deeter, David P. (1993). Disease and the Environment. Government Printing Office. p. 187.

- Flicker, H.; Loferski, J. J.; Elleman, T. S. (1964). "Construction of a promethium-147 atomic battery". IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 11 (1): 2. Bibcode:1964ITED...11....2F. doi:10.1109/T-ED.1964.15271.

- Jones, James William; Haygood, John R. (2011). The Terrorist Effect – Weapons of Mass Disruption: The Danger of Nuclear Terrorism. iUniverse. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4620-3932-6. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- Stwertka, Albert (2002). A guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-19-515026-1.

- Radioisotope Power Systems Committee, National Research Council U.S. (2009). Radioisotope power systems: an imperative for maintaining U.S. leadership in space exploration. National Academies Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-309-13857-4.

- https://www.msdsdigital.com/system/files/PHILIPS-CFL-15MM.pdfMSDS for the Philips CFL lamps containing Pm-147.

- Simmons, Howard (1964). "Reed Business Information". New Scientist. 22 (389): 292.

- Operator, organizational, direct support, and general support maintenance manual: installation, operation, and checkout procedures for Joint-Services Interior Intrusion Detection System (J-SIIDS). Headquarters, Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force. 1991. p. 5.

- Stuart Hunt & Associates Lt. "Radioactive Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-15. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

Bibliography

- Emsley, John (2011). Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 428–430. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- Lavrukhina, Avgusta Konstantinovna; Pozdnyakov, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich (1966). Аналитическая химия технеция, прометия, астатина и франция (Analytical Chemistry of Technetium, Promethium, Astatine, and Francium) (in Russian). Nauka.

- 2013, E.R. Scerri,A tale of seven elements, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 9780195391312