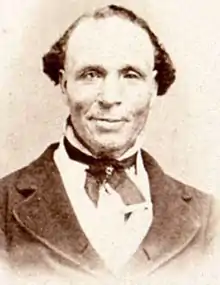

Elijah Abel

Elijah Abel, or Able or Ables[1] (July 25, 1808– December 25, 1884)[2] was one of the earliest African-American members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and was the church's first African-American elder and Seventy.[3] Abel was predominantly of Scottish and English descent[4] and appears to have been the first, and one of the few, black members in the early history of the church to have received Priesthood ordination,[3][5] later becoming the faith's first black missionary.[3] Abel did not have his ordination revoked when the LDS Church officially announced its now-obsolete restrictions on Priesthood ordination, but was denied a chance to receive his temple endowment by third church president John Taylor.[6] As a skilled carpenter, Abel often committed his services to the building of LDS temples and chapels. He died in 1884 after serving a mission to Cincinnati, Ohio, his last of three total missions for the church.[7][8]

| Elijah Abel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Third Quorum of the Seventy | |

| December 20, 1836 – December 25, 1884 | |

| Called by | Joseph Smith |

| Elder | |

| January 25, 1836 – December 20, 1836 | |

| Called by | Joseph Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 25, 1808 Frederick-Town, Maryland |

| Died | December 25, 1884 (aged 76) Salt Lake City, Utah Territory |

| Resting place | Salt Lake City Cemetery 40°46′37.92″N 111°51′28.8″W |

Early life

Elijah Abel was born in Frederick-Town, Maryland, on July 25, 1808, to Delilah Williams and Andrew Abel.[9] There is some confusion surrounding Abel's birth year, given that some sources put the year at 1808 and others at 1810.[10][11][12][13] However, the 1850 Census record marks 1808 as the year of Abel's birth,[14] and both Abel's patriarchal blessing and grave marker record 1808 as his birth year.[2][15] His mother was of Scottish descent and his father of English descent; one of his grandmothers was "half white", or mulatto,[1][4][11][3] and thus Abel was considered to be "octoroon," or one-eighth African.[4]

Abel's mother died when he was 8 years old.[4] Some believed that she was a slave from South Carolina,[16] but evidence for this has never been produced.[3] Others have also speculated, based on the unproven assumption that Abel was the son of a slave, that he at some point migrated to Canada by way of the underground railroad.[17] Apart from circumstantial evidence, this claim remains entirely unsubstantiated, apart from a few sources stating that Abel spent some time in Canada in his early adulthood.[18]

Conversion to the LDS faith

Abel later moved to Ohio,[19][7] and in Cincinnati he was baptized and confirmed a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in September 1832.[4] He was baptized by local Mormon elder and blacksmith Ezekiel Roberts.[11][7] Shortly after his baptism, Abel moved to the area of Kirtland, Ohio, to join in fellowship with the main body of church members congregating there.[20][7][21]

Priesthood ordination and church participation

Abel was ordained an elder of the LDS Church on January 25, 1836, following Joseph Smith's declaration in 1836 that Abel was "entitled to the Priesthood and all the blessings."[4][22] He had been an active participant in the construction of the Kirtland Temple over the preceding months.[23] Abel participated in the "Pentecostal season" that accompanied the completion and dedication of the Kirtland Temple in 1836.[24] In December of that year, 11 months after his priesthood ordination, Abel was ordained a seventy and inducted into the Third Quorum of the priesthood. In 1841, Abel was reconfirmed in Nauvoo by Joseph Young and Albert P. Rockwood.[4][17] Abel was among the first church members to receive the ordinance of the initiatory in the Kirtland Temple following its dedication in 1836.[4]

Patriarchal blessing

Abel received his patriarchal blessing from Presiding Patriarch Joseph Smith Sr.,[25] which was recorded by LDS Church scribe and newspaper editor Warren A. Cowdery.[26][10][21] At the time, the common practice when giving patriarchal blessings was to declare an individual to be a descendant of a specific tribe of Israel. Abel, however, was declared an "orphan" from a father who "hath never done his duty toward [him]", but it was stated in the blessing that Abel would "be made equal to [his] brethren, and [his] soul be white in eternity and [his] robes glittering."[15][27] Since the recorded blessing does not specifically declare his tribal lineage, Abel was perhaps "adopted" into the House of Israel.[15] The blessing also included what seemed to be a foreshadowing of the civil war that would soon strike at the heart of the country:[3][28]

Thou shalt see [the destroyer's] power in laying waste the nations, & the wicked slaying the wicked, while blood shall run down the streets like water, and thy heart shall weep over their calamities. Angels shall visit thee and thou shalt receive comfort. They shall call thee blessed and deliver thee from thine enemies. They shall break thy bands and keep thee from afflictions.[15]

Mission to Upper Canada

During the late 1830s, Abel labored as a missionary in New York and Upper Canada, and preached among the African-American population in those areas.[7][21][28] In 1838, Abel baptized 25-year-old Eunice Ross Kinney while serving in St. Lawrence County, New York, who after Abel's death remembered him as a "powerful" minister, and one who had been "ordained by Joseph the martyr".[29][8][30] Abel taught Kinney and others he baptized that "the time was drawing near for [Christ's] coming",[28] but that He would not come "till God had a people prepared to receive Him, with all the gifts and blessings that adorned His church anciently."[31] In his ministry, Abel often quoted the Apostle Peter: "Think it not strange, brethren, concerning the fiery trials which are to try you...".[32][28]

Due to civil unrest and rebellion in Upper Canada, Abel's missionary travels were frequently punctuated with dangerous situations and persecutions. Such circumstances were certainly not unfamiliar to many Mormon missionaries of the time, nor to their leaders.[30] At one point during his mission, Abel was falsely accused of the murder of a family of six, and aggressively pursued by a mob bearing hot tar and feathers.[33][7]

Time in Nauvoo, temple building and civil marriage

Abel moved from Kirtland to Commerce (later renamed Nauvoo), Illinois, in 1839 upon returning from his mission to Canada.[27] He came to own a piece of property located northwest of the city on the banks of the Mississippi River.[3] While living in Nauvoo, Abel continued to further immerse himself in church work and activity, and is known to have performed at least two baptisms for the dead by proxy: one for a friend by the name of "John F. Lancaster", and one for his mother, Delilah.[21][7][34] One of Abel's duties included acting as an undertaker at the request of Joseph Smith—responsible for the fashioning of coffins and the digging of graves—in response to the malaria epidemic of 1839–40.[3][21] Abel continued to work as a carpenter; he was a member of the group called the House Carpenters of the Town of Nauvoo.

During Abel's time in Nauvoo he became personally acquainted with Joseph Smith.[35] As part of Abel's priesthood license, Joseph wrote that he recommended Abel as his "worthy brother in the Lord", one who is "duly authorized" to spread the gospel in a manner "equal to the authority of that Office".[36] In June 1841, Abel and six other men quickly mobilized themselves as an expeditionary militia force to attempt the rescue of Smith after his unlawful arrest by state officers at Quincy, Illinois. By the time they reached Quincy, however, Smith had obtained a writ of habeas corpus and had been returned safely to Nauvoo.[37][38]

In 1842, Abel left the deed to his Nauvoo property to William Marks[3] and returned to Cincinnati on assignment by Joseph Smith.[7][27] There, he continued his carpentry and boarded for a time with a local painter named John Price on Eighth Street.[39] Abel continued to act as a leader of the church in Cincinnati, and was recognized as such by Joseph Smith, who pronounced to Orson Hyde and others: "Go to Cincinnati... and find an educated negro, who rides in his carriage, and you will see a man who has risen by the power of his own mind to his exalted state of respectability."[40][27]

Marriage

On February 16, 1847, the 39-year-old Abel married 17-year-old Mary Ann Adams[41] of Tennessee, who was residing in Ohio.[14][7][21] Adams was also one-eighth African-American.[21][4] Little is known about Adams, other than the date of her marriage to Abel and her residency status in both Tennessee and Ohio.[42] The couple had eight known children: three were born in Cincinnati—Moroni, Enoch, and Anna Rebecca[41]—and five more in Utah Territory—Delilah, Mary, Elijah Jr., Maggie, and Flora.[42][7] They also took into their home a young woman (about the age of their oldest son) named Rola from Ohio, whom they later adopted.[7]

Migration and later years in Utah

In May 1853, Abel and his family departed from Keokuk, Iowa, and migrated as part of the Appleton M. Harmon pioneer company to Utah Territory, where the new headquarters of the LDS Church were located.[43][27] After the company's arrival in the Salt Lake Valley on October 17, Abel's family moved to Millcreek, a few miles south of Salt Lake City.[44] Abel continued to work as a carpenter as part of the LDS public works program[45][21] and assisted in the construction of the Salt Lake Temple.[23] By 1860, the Abel family had moved to Salt Lake City's Thirteenth Ward and lived only a short distance from the Temple Block.[46]

Abel remained a member of the Seventy and continued to be active in the church in Utah. Along with his wife and oldest son, Abel was rebaptized on March 15, 1857, as part of the Mormon Reformation.[47][21] During the mass southern migration of LDS Church members in 1858 to avoid conflict with Johnston's invading army during the Utah War, Abel stayed behind with other watchmen who had been tasked with setting fire to the emptied city should the invaders make any false move; the U.S. troops marched through Salt Lake City without incident and the city remained intact.[7]

Abel and his wife managed the Farnham House hotel, which was advertised as a "first class" boarding house that boasted "good stabling and corrals".[46][48] By 1862, Abel and his family had relocated to the Tenth Ward in Salt Lake City.[3][43] Very little is known about the personal lives of the Abel family. In 1870 they moved to Ogden, Utah, for a short time before returning to Salt Lake City.[49] Utah residents during this period remembered the Abel family as traveling up and down the Wasatch front (a mountain valley stretch of contiguous towns from Provo to Ogden) entertaining audiences with their minstrel shows:

It seems most likely that Abel played the fiddle or violin, while the family – including eight children between the ages of about one and twenty years old – acted, danced, sang, or played along with their father on other instruments. "There was a family of colored folks by the name of Able [sic]," remembered one Utah resident, "who went around from ward to ward and put on performances for the public."[50]

In 1871, Abel's son Moroni passed away, followed by Abel's wife in 1877 from pneumonia.[51] Abel remained a faithful member of the LDS Church throughout his life and served a final mission to Ohio and Canada in 1883–84, during which he became ill. His worsening health resulted in his return to Utah in December 1884. Abel died two weeks after his return, on Christmas Day.[52][53] His body was interred at the Salt Lake City Cemetery alongside his wife, and his original grave marker is inscribed with the words: "Elijah Able—At Rest."[54]

Disputes over priesthood

Meeting in Cincinnati, 1843

On June 25, 1843, a regional conference occurred in Cincinnati presided over by LDS Church apostles John E. Page, Orson Pratt, Heber C. Kimball, and future-apostle Lorenzo Snow.[55] During the conference, questions regarding Abel and his membership were addressed, including the acknowledgement of recent complaints about Abel's public preaching activity.[10][7] Page stated that while "he respected a coloured Brother, wisdom forbid that we should introduce [him] before the public."[55] Pratt and Kimball supported Page's statements, and the leaders resolved to restrict Abel's activities as a member of the church.[55]

While previously in Canada, Abel's activity to encourage flight from Canada and its civil uprisings to the American "Zion" was viewed with disdain, and was seen by the Canadians as "pro-American sympathizing". The former missionary associates who accused him cited Abel's claims "that there would be stakes of Zion in all the world".[7][28] However, despite these allegations of teaching what was perceived by some to be "false doctrine",[56] no disciplinary action was taken against Abel.[3][7] At the conclusion of the conference, Abel was called to serve a second mission locally, but he was instructed to visit and teach "only the coloured population".[55] The leaders of the conference in Cincinnati made no statement that the resolution of the meeting had been based on divine revelation or that it constituted any sort of doctrinal mandate, but rather they deemed it prudent to address the dynamic racial and politically turbulent climate of the times.[8][55]

The 1849 priesthood ban

In 1849, Brigham Young issued a church-wide ban on black men from being ordained to the priesthood. The policy's initial reveal by Young to the Twelve may have occurred up to two years earlier at Winter Quarters, Nebraska.[57] Young's pronouncements in 1849 constitute the earliest known statements which officially exclude those of African descent from a temple endowment or the wielding of priesthood power. This decision may have been brought about in part by the actions of William McCary, an African-American convert to the church living in Cincinnati, who believed he was a prophet and claimed on various occasions to be Jesus and Adam, father of the human race.[10][7] In 1847, as the Saints resided at Winter Quarters, McCary was excommunicated, following the discovery of various unauthorized polygamous sealings performed in his home.[3][10][7] As members of the LDS Church continued to migrate to the West, Mormons were exposed to a larger population of blacks, and anti-black political attitudes continued to increase among church members.[8][10][7] Other black members of the church such as Q. Walker Lewis[3] also found themselves and their church membership under scrutiny during this period.

By 1847, Abel's priesthood authority had begun to be challenged, despite his well-respected status within the church community.[8][58] Even after the 1849 official prohibition for all Latter-day Saint "brethren of color," Abel remained involved in the church.[59] As one who already held the priesthood, he continued to serve as a seventy in Cincinnati from 1842 to 1853,[60] and in the autumn of 1883 served another mission to Cincinnati shortly before his death.[61]

Denial of temple ordinances

After moving to Utah Territory, Abel asked Brigham Young for permission to be sealed to his wife and children, which was denied.[8][21] Abel again requested a sealing five years later to his deceased wife, son, and daughter—this time from President John Taylor, who then passed it on for the body of the Twelve to consider.[3][21] Abel's request was again refused, and he was not allowed to enter the temple to be endowed.[8][21][62]

1879 meeting regarding Joseph Smith's statements

On May 31, 1879, a meeting was held at the residence of Provo mayor Abraham O. Smoot to discuss the conflicting versions of Joseph Smith's views on black men and the priesthood, in response to Abel's petition to be sealed to his recently deceased wife.[63][40] Abel had first been ordained to the priesthood by Ambrose Palmer in January 1836, then as a Seventy by Zebedee Coltrin in December of the same year.[1][4] Coltrin claimed, however, that Abel had been ordained as a Seventy in exchange for his work on the temples at Kirtland and Nauvoo, but that Joseph Smith had later realized his "error" and promptly "dropped" Abel from the quorum because of "his lineage".[21][40] Coltrin reported having this conversation with Joseph Smith in 1834—yet Abel had not received the priesthood nor had been made a Seventy until 1836, and construction had not even begun on the Nauvoo Temple until 1841, thus making it impossible to have been "dropped" from any such capacity in 1834.[40] Joseph F. Smith contradicted Coltrin by pointing out that he had verified as being in Abel's possession two certificates which notarized his 1836 and 1841 priesthood licensings that declared Abel to be an elder of the church and a seventy.[3][21]

The "Smoot meeting" was essentially a reaffirmation of the church's 1849 policy of excluding black men from receiving the priesthood. Beyond suddenly bringing into question Abel's long-held authority in a high-profile and likely humiliating setting, the meeting did not change the fact that Abel held the priesthood.[40]

1879 meetings with Taylor, Smith, and the Seventy

In 1879, Abel was present at two separate meetings regarding his priesthood authority.[1][4] At these meetings Abel had addressed the church members and authorities present and reflected upon his nearly 45 years of experience as a priesthood-bearing Latter-day Saint. He had also recounted "his appointment an[d] ordination as a Seventy, and a member of the 3rd Quorum." Abel recalled for them Joseph's personal words to him: "that those… called to the Melchisadec [sic] Priesthood [having] magnified that calling would be sealed up unto eternal life."[64][8][58] At these meetings, Abel himself defended his priesthood before church authorities, outlining its timeline and reaffirming that Joseph Smith himself had told him he was "entitled to the priesthood".[65][58] Abel expressed to President Taylor his lifelong hope that his endowment of priesthood might prove one day "the welding link" to bond all of God's people together regardless of race.[7] At the end of these meetings, John Taylor concluded that Joseph Smith had made "an exception" and had given Abel the priesthood despite his race—perhaps because he was of primarily European descent, and perhaps because he had further proved his worthiness by helping to advance and to build the early church. Taylor moved to honor Smith's decision and ruled that Abel's priesthood would be "allowed to remain".[8][58]

Posthumous commentary on Abel's priesthood

After Abel's death, LDS Church president Joseph F. Smith on multiple occasions[3][8][40] declared Abel's ordination to the priesthood as "null and void by [Joseph Smith] himself because of his blackness", suggesting based on Coltrin's previous testimony that Joseph Smith before his death had indeed repented of his initial decision that Abel receive the priesthood.[8][27] Scarcely a few years had passed since Joseph F. Smith had himself been the one to ordain Abel and to set him apart to serve his final church mission.[8][21] Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith, who later became president of the church, went so far as to suggest that there had been two Elijah Abels – one white and one black.[66][21]

Legacy

Following Abel's death in 1884, his life and ordination to the priesthood remained a topic of conversation and debate for decades. The circumstance and story of Elijah Abel often were referenced with the rise of questions concerning black men receiving the priesthood or temple blessings.[53] All eligible men within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were admitted to the priesthood beginning in 1978, when all former restrictions based on race were lifted with the revelation received by then-prophet and church president Spencer W. Kimball. Long before this, however, Abel's son and grandson, Enoch and Elijah, had both been ordained already to the Melchizedek priesthood; Enoch was ordained an elder on November 27, 1900, and Elijah to the same office on September 29, 1935.[8][67]

In 2002, a monument was erected in Salt Lake City over Abel's gravesite by the Missouri Mormon Frontier Foundation and the Genesis Group, to memorialize Abel, his wife, and his descendants.[7][67] The monument was dedicated by LDS Church Apostle M. Russell Ballard.[68]

Front of Grave Marker

Front of Grave Marker Back of Grave Marker

Back of Grave Marker

See also

Notes

- Smith, Joseph F. (1810–1884). "Elijah Able". The Joseph Smith Papers Project. Salt Lake City, Utah. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- Grave Marker of Elijah Abel. (Inscribed front). File:ElijahAbelGraveFront.jpg

- Jackson 2013.

- Smith c. 1879.

- Bowman, Matthew (2012). "Chapter 2: Little Zions: 1831-1839". The Mormon People: The Making of an American Faith. New York: Random House. p. 46. ISBN 978-0679644903.

- 125: Elijah Ables' Attempt for Temple Blessings (Part 5 of 6 Russell Stevenson), archived from the original on December 12, 2021, retrieved May 21, 2021

- Stevenson 2013.

- Reeve 2015.

- Jackson 2013, pp. 10–11.

- Bringhurst 1984.

- Reasons; Patrick (July 15, 1971). "They Had a Dream: Elijah Abel". The Troy Record. Troy, New York. p. 18. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- Hawkins 1985.

- Anderson, Martha (1980). Black Pioneers of the Northwest 1800–1918. p. 217.

- 1850 Census. The census record registers Mary Ann Adams Abel as being 19 years old, and her husband Elijah Abel as being 42 years old, which effectively pushes back his birthdate to 1808.

- Patriarchal Blessing of Elijah Abel, c. 1836, recorded by W. A. Cowdery with penned preamble, "[Patriarchal] Blessing of Elijah Able [sic] who was born in Frederick County, Maryland, July 25th 1808." "Joseph Smith’s Patriarchal Blessing Record" (1833–1843), 88. LDS Church Archives.

- Bush, Jr., Lester E. (1984). "Chapter 2: A Commentary on Stephen G. Taggart's 'Mormonism's Negro Policy: Social and Historical Origins'. Note 8". In Bush Jr., Lester E.; Mauss, Armand L. (eds.). Neither White nor Black: Mormon Scholars Confront the Race Issue in a Universal Church. Midvale, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 9780941214223. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- Hawkins 1985, p. 2.

- Jackson 2013, p. 20.

- Jackson 2013, p. 23.

- Jackson 2013, p. 31.

- Embry 1994.

- Jackson 2013, p. 55.

- Jackson 2013, p. 47.

- Jackson 2013, pp. 49–54.

- Jenson, Andrew (1936). Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. Salt Lake City, Utah: The Andrew Jenson History Company. p. 697 (4 volumes: 1901-1936). It appears that the blessing was pronounced on or after March 30, 1836, when the "washing" ordinance was first introduced to the Saints and nearer the time of Abel's priesthood licensing on March 31; or perhaps in December, at the time of his ordination as a Seventy. ISBN 978-1589580312.

- Jackson 2013, pp. 56–60.

- Bringhurst 1981.

- Underwood, Grant (1999) [1993]. The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 26–36, 49–51, 63–72. ISBN 978-0252068263.

- Kinney, Eunice. (July 5, 1885). Letter to Wingfield Watson. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah. See also Eunice Kinney, "My Testimony of the Latter Day Work". (c. 1885). Microfilm typescript, MS 4226. LDS Church Archives.

- Hawkins 1985, p. 3.

- Jackson 2013, p. 65.

- Jackson 2013, p. 66.

- Jackson 2013, pp. 66–67.

- Hawkins 1985, p. 4.

- Jackson 2013, p. 7.

- Priesthood License of Elijah Abel. (March 31, 1836). Recorded by Joseph Smith, Jr. and Frederick G. Williams. Michael Marquardt Papers, box 6, folder 1. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah. See also a scanned image of the certificate at the online document repository of The Joseph Smith Papers Project.

- Prince, Stephen L. (2017). "Chapter 7: Rising Through the Ranks". Hosea Stout: Lawman, Legislator, Mormon Defender. Logan: Utah State University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-1607326403.

- History of the Church, 4:365.

- Jackson 2013, p. 79.

- Givens, Terryl L.; Barlow, Philip L., eds. (2015). "Chapter 24: Mormons and Race". The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism. Oxford Handbooks. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199778362.

- Mary Adams' Parents. The Ohio county of residence of Mary Ann's parents (John and Anna Weston Adams) at the time of their deaths — Hamilton, located just 15 miles north of Cincinnati – is, curiously, the home county of Ezekiel Roberts, the Mormon elder who baptized Elijah Abel in 1832. Stevenson (2014) suggests, therefore, that Hamilton County may have been where Elijah was baptized. But also, as Mary's family were erstwhile residents of Hamilton (perhaps moving there, to Mount Healthy township, after Mary's birth in Nashville), it may also have been where Elijah was first introduced to Mary. Hamilton County lies 60 miles south of Miami County, where lived, according to Jackson (2013), a possible sister of Elijah, Nancy Abel Rousten.

- Jackson 2013, p. 84.

- Coleman, Ronald Gerald (1980). A History of Blacks in Utah: 1825–1910. Harold B. Lee Library; Provo, Utah: Unpublished. p. 59.

- Jackson 2013, p. 90.

- Jackson 2013, pp. 94.

- Jackson 2013, p. 91.

- Jackson 2013, pp. 90–91.

- "Elijah Abel". blacklds.org. May 27, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- Hawkins 1985, p. 6.

- Jackson 2013, p. 95.

- Jackson 2013, pp. 95–96.

- Jackson 2013, p. 103.

- Hawkins 1985, p. 8.

- "Cemeteries and Burials Database: Burial Information: ABLE, ELIJAH and ABLE, MARY". Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah Division of State History. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- Jackson 2013, p. 77.

- The allegations against Abel had originally surfaced in a June 1, 1839, meeting convened at Quincy, Illinois – during the time when Joseph Smith was laboring with the struggling Missouri-driven Saints in establishing their new home at Commerce (Nauvoo). As such, Smith was not present at the hearing. Convened at the Quincy meeting were quorum members and presiding officers of the Seventy, as well as a young Jedediah M. Grant. Grant had been selected as the priesthood representative to convey to the body of the Seventy the complaints brought before them by Abel's missionary associates. Abel himself was in absentia. Also testifying at the hearing were John Broeffle and his cousins John & George Beckstead, Robert Burton, and Moses Smith. Abel had previously been offered refuge in the Becksteads' father's home while being pursued by a mob (Stevenson, 2013, p. 200).

- Esplin, Ronald K. (1979). "Brigham Young and Priesthood Denial to the Blacks: An Alternate View". BYU Studies Quarterly. Vol. 19, no. 3. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University. pp. 394–402. Esplin's argument is not generally accepted, not only in light of Joseph Smith's 1836 priesthood sanctioning and licensing of Abel, but also given Young's conciliatory and apparently open views on the issue as evidenced in his March 1847 remarks to William McCary. Esplin does point out, however, that Young – in his remarks of February 5, 1852, to the Utah Territorial Legislature (the day after slavery had been codified into Utah law) — promised that there would be a future general bestowal of the priesthood to blacks: "That time will come when they will have the privilege of all we have the privilege of and more". Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Jackson 2013, p. 99.

- A formal reiteration of LDS Church policy regarding the 1849 priesthood ban was codified into law by Utah's territorial legislature on February 4, 1852, one month after Governor Brigham Young appeared before that body on January 16 to formally petition for the policy's codification. See Lester E. Bush, Jr. (1984). Chapter 3: "Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview," in Lester E. Bush, Jr. and Armand L. Mauss (eds). Neither White nor Black: Mormon Scholars Confront the Race Issue in a Universal Church. Midvale, Utah: Signature Books.

- Meeting Minutes, June 25, 1843. "Conference of Elders of the Church," Cincinnati, Ohio. LDS Church Archives.

- "Deaths," Deseret News, December 25, 1884.

- Jackson 2013, p. 100.

- Jackson 2013, p. 96.

- "A Record of all the Quorums of Seventies in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". (March 5, 1879). CR3/51, box 3, folder 2. LDS Church Archives.

- "Council Meeting Minutes". (June 4, 1879). Lester E. Bush papers, Special Collections, J. Williard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

- Letter of Joseph Fielding Smith to Mrs. Floren S. Preece, January 18, 1955. S. George Ellsworth Papers, Utah State University, Logan (see also Letter from Joseph Fielding Smith to Joseph H. Henderson, April 10, 1963).

- Bringhurst, Newell G.; Smith, Darron T., eds. (2006). "The 'Missouri Thesis' Revisisted: Early Mormonism, Slavery, and the Status of Black People". Black and Mormon. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 13–33, at p. 30. ISBN 978-0252029479

- Arave, Lynn (September 30, 2002). "Monument in S.L. erected in honor of black pioneer". Deseret Morning News. p. B3. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

Sources

- Jackson, W. Kesler (2013). Elijah Abel: The Life and Times of a Black Priesthood Holder. Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1462111510.

- Hawkins, Chester L. (December 4, 1985). Report on Elijah Abel and His Priesthood. L. Tom Perry Special Collections; Harold B. Lee Library: Unpublished. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- Bringhurst, Newell G. (1981). Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 131–133, 149. ISBN 978-0313227523.

- Embry, Jessie L. (1994). "Chapter 3: Impact of the LDS 'Negro Policy'". Black Saints in a White Church: Contemporary African American Mormons. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 978-1560850441.

- Stevenson, Russell W. (2014). Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables (self-published). CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1500843137.

- Bringhurst, Newell G. (1984). "Chapter 4: Elijah Abel and the Changing Status of Blacks Within Mormonism". In Bush Jr., Lester E.; Mauss, Armand L. (eds.). Neither White nor Black: Mormon Scholars Confront the Race Issue in a Universal Church. Midvale, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 9780941214223. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Reeve, W. Paul (2015). "Chapter 7: Black, White, and Mormon: 'One Drop'". Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 194–210. ISBN 978-0199754076.

- Stevenson, Russell W. (2013). "A Negro Preacher: The Worlds of Elijah Ables" (PDF). Journal of Mormon History. Vol. 39, no. 2. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 250. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Smith, Joseph F. (c. 1879). "Joseph F. Smith biographical transcript for Elijah Able, Joseph F. Smith Papers" (PDF). The Joseph Smith Papers Project. Salt Lake City, Utah. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

Further reading

- "Elijah Able," The Joseph Smith Papers.

- Joseph F. Smith biographical transcript for Elijah Able, as catalogued by The Joseph Smith Papers.

- "Elijah Abel and the Changing Status of Blacks Within Mormonism". (1979). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 12(2):22–36.

- "Deaths," Deseret News, 31 December 1884:16.

- Sessions, Gene A. (2008) [1982]. Mormon Thunder: A Documentary History of Jedediah Morgan Grant. Second Edition. Greg Kofford Books: Draper, Utah. ISBN 978-0252009440. Original publisher: Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Underwood, Grant. (1999) [1993]. The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252068263

External links

- Elijah Abel Black LDS site

- Mormon Central Catalogued LDS Church documentation and correspondence regarding blacks and the priesthood