Elisabet Ney

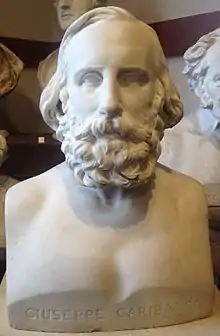

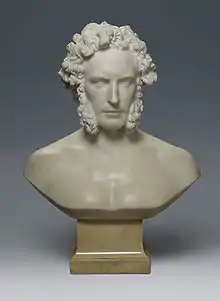

Franzisca Bernadina Wilhelmina Elisabeth Ney (26 January 1833 – 29 June 1907) was a German-American sculptor who spent the first half of her life and career in Europe, producing portraits of famous leaders such as Otto von Bismarck, Giuseppe Garibaldi and King George V of Hanover. At age 39, she immigrated to Texas with her husband, Edmund Montgomery, and became a pioneer in the development of art there. Among her most famous works during her Texas period were life-size marble figures of Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin, commissions for the Texas State Capitol. A large group of her works are housed in the Elisabet Ney Museum, located in her home and studio in Austin. Other works can be found in the United States Capitol, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and numerous collections in Germany.

Elisabet Ney | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Franzisca Bernadina Wilhelmina Elisabeth Ney January 26, 1833 |

| Died | June 29, 1907 (aged 74) Austin, Texas, U.S. |

| Nationality | German, American |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Spouse | Edmund Montgomery |

| Memorial(s) | Elisabet Ney Museum |

Early life

Ney was born in Münster, in the Province of Westphalia, to Johann Adam Ney, a stonecarver and alleged nephew of Field Marshal Michel Ney,[1] and Anna Elizabeth on January 26, 1833.[2][3] The only other surviving child in the Ney family was her older brother, Fritz. Her parents were Catholics of Alsatian-Polish heritage. She was the great-niece of Michel Ney, Marshal of France. Early in life, she declared that her goal was "to know great persons."[4][1]

Career

Europe

Ney grew up assisting her father in his work. She went on a weeks-long hunger strike when her parents opposed her becoming a sculptor, prompting her parents to request the assistance of their local bishop. Her parents finally relented and in 1852, she became the first female sculpture student at the Munich Academy of Art under professor Max von Widnmann. She received her diploma on July 29, 1854. After graduating she moved to Berlin to study under Christian Daniel Rauch.[5][6][2][3] Under Rauch she studied realism and the German artistic tradition, and began sculpting her first portraits of the German elite.[2]

Ney opened a studio in Berlin in 1857. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer agreed to sit for a sculpted portrait at the persuasion of Edmund Montgomery, whom she would marry in 1863. It was hailed as an artistic success and led to other commissions, most notably Jacob Grimm of the Brothers Grimm, the Italian military leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, the composer Richard Wagner, Cosima von Bülow (the daughter of Franz Liszt and Wagner's future wife), the Prussian-German political figure Otto von Bismarck, and King George V of Hanover. The latter also commissioned bust portraits of the composer Josef Joachim and his wife, the contralto Amalie Weiss Joachim. Shortly after completing the Bismarck bust, Ney was commissioned in 1868 by Prussian agents to sculpt a full-length portrait of Ludwig II of Bavaria in Munich.[4][7]

United States

In the early 1880s, Ney, by then a Texas resident, was invited to Austin by Governor Oran M. Roberts, which resulted in the resumption of her artistic career.[8] In 1892, she built a studio named Formosa in the Hyde Park neighborhood north of Austin and began to seek commissions.[4][9][3][2]

In 1891, Ney was commissioned by the Board of Lady Managers of the Chicago World's Fair Association, and supplemented with US$32,000 by the Texas state legislature, to model figures of Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin for the Woman's Building at the World's Columbian Exposition World's Fair in 1893.[4][10][11] Ney missed the deadline and the sculptures were not shown at the Exhibition.[12] The marble sculptures of Houston and Austin can now be seen in both the Texas State Capitol in Austin and in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. She was commissioned to sculpt a memorial to the career military officer and war hero Albert Sidney Johnston for his grave in the Texas State Cemetery.[3][2][13] One of her signature works was the figure of Lady Macbeth; the plaster model is in the Elisabet Ney Museum and the completed marble is in the Smithsonian American Art Museum collection.[2] She succeeded in having the orator, three-time presidential candidate, and noted attorney William Jennings Bryan sit for a portrait; she hoped to sell replicas of this bust to debate clubs across the country.

Her 1903 life-size portrait bust of David Thomas Iglehart can be found at Symphony Square in Austin, where it is on permanent loan to the Austin Symphony Society.[14] What is considered to be possible the last known work of Ney, a sculpture of a tousled haired cherub resting over a grave and known as the 1906 Schnerr Memorial, can be found at Der Stadt Friedhof in Fredericksburg, Texas.[15]

In addition to her sculpting activities, Ney was also active in cultural affairs in Austin. Formosa become a center for cultural gatherings and curiosity seekers. The composer Paderewski and the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova were among her visitors.[4]

Personal life

While visiting friends in Heidelberg in 1853, Ney met a young Scottish medical student, scientist, and philosopher[16] named Edmund Montgomery. They kept in touch, and, although she viewed the institution of marriage as a state of bondage for women, after he established a medical practice in Madeira, they were married at the British consulate there on November 7, 1863.

Ney, however, remained outspoken about women's roles. She refused to use Montgomery's name, often denied she was even married, and once remarked:[4][1][17]

Women are fools to be bothered with housework. Look at me; I sleep in a hammock which requires no making up. I break an egg and sip it raw. I make lemonade in a glass, and then rinse it, and my housework is done for the day.

She wore pants and rode her horses astride as men did. She liked to fashion her own clothes, which, in addition to the slacks, included boots and a black artist frock coat.[6]

Montgomery was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1863. By 1870, the Franco-Prussian War had begun. In autumn of that year, Ney became pregnant with their first child. Montgomery received a letter from his friend, Baron Carl Vicco Otto Friedrich Constantin von Stralendorff of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, who had moved to Thomasville, Georgia with his new wife, Margaret Elizabeth Russell of Boston, Massachusetts, declaring the location "Earth's paradise."[18] On January 14, 1871, Ney and Montgomery, accompanied by their housekeeper, Cenci, immigrated to Georgia, to a colony promoted as a resort for consumptives. Their first son, Arthur, was born there in 1871, but died two years later (possibly of diphtheria, but the cause of death is disputed).[1][19] Unfortunately, the Thomasville colony did not work out as they had hoped. Baron and Baroness von Stralendorff returned to Wismar, Germany where he died on July 1, 1872.[20][21][22]

Ney and Montgomery looked elsewhere in the United States for a place to live, including Red Wing, Minnesota, where their second son, Lorne (1872–1913), was born. Later that year, Ney traveled alone to Texas. With the help of Julius Runge a businessman in Galveston, she was shown Liendo Plantation near Hempstead in Waller County. On March 4, 1873, Montgomery and the rest of the family arrived, and they purchased the plantation. While he tended to his research, she ran it for the next twenty years.

Death and legacy

Ney died in her studio on June 29, 1907, and is buried next to Montgomery, who died four years later, at Liendo Plantation.[23]

Upon her death, Montgomery sold the Formosa studio to Ella Dancy Dibrell. As per her wishes, its contents were bequeathed to the University of Texas at Austin, but were to remain in the building. On April 6, 1911, Dibrell and other friends established the Texas Fine Arts Association (after more than a century in existence, the organization is now known as the Contemporary Austin) in her honor.[3][2][24] It is the oldest Texas-wide organization existing for support of the visual arts. Formosa is now the home of the Elisabet Ney Museum. In 1941, the City of Austin took over the ownership and operation.[8][11][25]

In 1961, Lake Jackson Primary School in Lake Jackson, Texas was renamed Elisabet Ney Elementary School in her honor.[26]

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

Elisabeth Ney c. 1859 with a bust of Arthur Schopenhauer

Elisabeth Ney c. 1859 with a bust of Arthur Schopenhauer

Elisabet Ney in her Atelier in Texas circa 1900

Elisabet Ney in her Atelier in Texas circa 1900

Tomb of Albert Sidney Johnston in the Texas State Cemetery

Tomb of Albert Sidney Johnston in the Texas State Cemetery

Works

Below is a partial listing of her works.[27]

| Year | Work | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1855 | Johann Adam Ney | Munster |

| 1855 | Anna Elisabeth Wernze Ney | Munster |

| 1855 | Tyras – Adam Ney's Dog | Munster |

| 1856 | Grave Stele Relief | Berlin |

| 1856 | Herman Weiss | Berlin |

| 1857 | St. Sebastian Martyr – plaster | Munster |

| 1857 | St. Sebastian Martyr – marble | Munster |

| 1857 | St. Sebastian Resurrected | Munster |

| 1857 | Christ Resurrected | Munster |

| 1858 | Jacob Grimm – marble | Berlin |

| 1858 | Alexander von Humboldt | Berlin |

| 1858 | Cosima von Bülow | Berlin |

| 1859 | Arthur Schopenhauer – plaster | Frankfurt |

| 1859 | Arthur Schopenhauer – marble | Frankfurt |

| 1859 | King George V of Hanover – medallion | Hannover |

| 1859 | King George V of Hanover – bust | Hannover |

| 1859 | King George V of Hanover – colossal bust | Hannover |

| 1861 | Joseph Joachim | Hannover |

| 1861 | Eilhard Mitscherlich - plaster | Hannover |

| 1861 | Ernst Herzog von Bayern | Munster |

| 1861 | Franz Friedrich von Furstenberg – figure | Munster |

| 1862 | Walter von Platenberg – study | Munster |

| 1862 | Walter von Platenberg – figure | Munster |

| 1862 | Count Englebert Vandermark – study | Munster |

| 1861 | Count Englebert Vandermark – figure | Munster |

| 1862 | Justus Möser – figure | Munster |

| 1863 | Ricci | England |

| 1863 | Elisabet Ney self-portrait | Madeira |

| 1863 | Thomas Taylor | England |

| 1863 | Genii of Mankind – plaster | England |

| 1863 | Self-Portrait – plaster | England |

| 1863 | Self-Portrait – marble | Madeira |

| 1863 | Eilhard Mitscherlich - marble | Hannover |

| 1864 | Edmund Montgomery – plaster | Madeira |

| 1864 | Edmund Montgomery – marble | Madeira |

| 1864 | Lady Marian Alford | Madeira |

| 1864 | Lord Brownlow | Madeira |

| 1864 | Genii of Mankind – marble | Italy |

| 1865 | Giuseppe Garibaldi – statuette | Italy |

| 1865 | Giuseppe Garibaldi – plaster | Italy |

| 1865 | Giuseppe Garibaldi – marble | Italy |

| 1865 | Prometheus Bound | Austria |

| 1867 | Otto von Bismarck – plaster | Berlin |

| 1867 | Otto von Bismarck – marble | Berlin |

| 1867 | Amalie Weiss Joachim | Hannover |

| 1868 | Friedrich Woehler – bust | Munich |

| 1868 | Friedrich Woehler – colossal bust | Munich |

| 1868 | Baron Justus von Liebig – bust | Munich |

| 1868 | Baron Justus von Liebig – colossal bust | Munich |

| 1868 | Mercury – study | Munich |

| 1868 | Mercury – colossal figure | Munich |

| 1868 | Iris – study | Munich |

| 1868 | Iris – full figure | Munich |

| 1868 | Draped Figure – study | Munich |

| 1868 | Male Figure – study | Munich |

| 1868 | Frieze – study | Munich |

| 1868 | Fountain – study | Munich |

| 1868 | Count Georg von Werthern | Munich |

| 1868 | King Ludwig II – plaster | Munich |

| 1868 | King Ludwig II – marble | Munich |

| 1868 | King Ludwig II – life-size plaster | Munich |

| 1874 | Lorne Ney Montgomery – castings | Texas |

| 1885 | Oran M. Roberts – plaster | Texas |

| 1885 | Oran M. Roberts – marble | Texas |

| 1886 | Lorne Ney Montgomery | Texas |

| 1887 | Johanna Runge | Texas |

| 1887 | Julius Runge | Texas |

| 1892 | Benedette Tobin | Texas |

| 1892 | Sam Houston as Young Man – plaster bust | Texas |

| 1892 | Sam Houston as Older Man – bronze bust | Texas |

| 1892 | Sam Houston – life-size plaster | Texas |

| 1892 | Sam Houston – life-size marble | Texas |

| 1892 | Stephen F. Austin – study | Texas |

| 1892 | Stephen F. Austin – plaster bust | Texas |

| 1893 | Stephen F. Austin – life-size plaster | Texas |

| 1893 | Stephen F. Austin – life-size marble | Texas |

| 1893 | Governor W.P. Hardeman – plaster | Texas |

| 1893 | Governor W.P. Hardeman – marble | Texas |

| 1895 | Carrie Pease Graham – plaster | Texas |

| 1895 | Carrie Pease Graham – marble | Texas |

| 1895 | Senator John H. Reagan – plaster | Texas |

| 1895 | Senator John H. Reagan – marble | Texas |

| 1895 | Governor Francis R. Lubbock – plaster | Texas |

| 1895 | Governor Francis R. Lubbock – marble | Texas |

| 1896 | Paula Ebers – plaster | Berlin |

| 1896 | Paula Ebers – marble | Berlin |

| 1896 | Unknown Female Philanthropist | Berlin |

| 1896 | Unknown girl | Berlin |

| 1896 | Unknown woman | Berlin |

| 1896 | Dancing Maenid | Berlin |

| 1897 | Bride Neill Taylor – medallion | Texas |

| 1897 | Margaret Runge Rose – plaster | Texas |

| 1897 | Margaret Runge Rose – bronze | Texas |

| 1899 | Sir Swante Palm – plaster | Texas |

| 1899 | Sir Swante Palm – marble | Texas |

| 1899 | Lilly Haynie | Texas |

| 1899 | Steiner Burleson – plaster | Texas |

| 1899 | Steiner Burleson – marble | Texas |

| 1899 | William Jennings Bryan – plaster | Texas |

| 1899 | William Jennings Bryan – marble | Texas |

| 1900 | Guy M. Bryan – medallion | Texas |

| 1901 | Senator Joseph Dibrell – plaster | Texas |

| 1901 | Senator Joseph Dibrell – marble | Texas |

| 1901 | Ella Dancy Dibrell – medallion | Texas |

| 1901 | Governor Joseph Sayers – plaster | Texas |

| 1902 | Governor Joseph Sayers – marble | Texas |

| 1902 | Governor Sul Ross – plaster | Texas |

| 1902 | Governor Sul Ross – marble | Texas |

| 1902 | Bust of Christ | Texas |

| 1902 | Albert Sidney Johnston – bust | Texas |

| 1902 | Albert Sidney Johnston – life-size plaster | Texas |

| 1902 | Albert Sidney Johnston – life-size marble | Texas |

| 1902 | Jacob Bickler – medallion | Texas |

| 1902 | Lady Macbeth – study | Texas |

| 1902 | Lady Macbeth – life-size plaster | Texas |

| 1902 | Lady Macbeth – life-size marble | Texas |

| 1903 | Dr. David Thomas Iglehart – plaster | Texas |

| 1902 | Dr. David Thomas Iglehart – bronze | Texas |

| 1903 | Miller Baby cast | Texas |

| 1904 | Helen Marr Kirby | Texas |

| 1905 | Dr. William Lamdin Prather | Texas |

| 1906 | Schnerr Memorial – wax | Texas |

| 1906 | Schnerr Memorial – plaster | Texas |

| 1906 | Schnerr Memorial – marble | Texas |

References

- Ledbetter, Suzann (2006). Shady Ladies: Nineteen Surprising and Rebellious American Women. Forge Books. pp. 179–192. ISBN 978-0-7653-0827-6.

- Cutrer, Emily. "NEY, ELISABET". The Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- Ney-Montgomery Papers #60, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

- Abernathy, Francis Edward (1994). Legendary Ladies of Texas. University of North Texas Press. pp. 95–105. ISBN 978-0-929398-75-4.

- Reimers, Peggy A (2006). Lone Star Legends. P.A. Reimers. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-4276-0624-2.

- Ingham, Donna (2006). You Know You're in Texas When... Globe Pequot. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7627-3811-3.

- "Elisabet Ney Education 1863–1857". City of Austin Parks and Recreation Dept. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- Little, Carol Morris (1996). A Comprehensive Guide to Outdoor Sculpture in Texas. University of Texas Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0-292-76034-9.

- "Elisabet Ney-Formosa studio". City of Austin Parks and Recreation Dept. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Walton, Andrea (2005). Women and Philanthropy in Education. Indiana University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-253-34466-3.

- Fisher, James D. "Elisabet Ney Museum". Handbook of Texas online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- Nichols, K. L. "Women's Art at the World's Columbian Fair & Exposition, Chicago 1893". Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Baird, David (2009). Frommer's San Antonio and Austin. Frommers. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-470-43789-6.

- Little, Carol Morris, 1996, p75

- "Elizabeth Emma Schneider Schnerr". Der Stadt Friedhof. Fredericksburg Genealogical Society. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- "Elisabet Ney (1833-1907)". 4 December 2020.

- Lau, Barbara (July 1981). "The Woman Who Found The Women". The Alcalde: 14.

- "Elisabet Ney Emigration 1871–1873". City of Austin Parks and Recreation Dept. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- Meischen, Betty Smith (2002). From Jamestown to Texas. IUniverse. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-0-595-24223-8.

- New England Historic Genealogical Society Staff (1873). The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. New England Historic Genealogical Society Staff. p. 291.

- Stephens, Ira Kendrick (1951). The Hermit Philosopher of Liendo. Southern Methodist University Press. p. 136.

- "Edmund Montgomery and Elisabet Ney papers". SMU. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- "Liendo Plantation". Archived from the original on 22 October 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- Shukalo, Alice. "TEXAS FINE ARTS ASSOCIATION". The Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- Cohen, Rebecca S (2004). Art Guide Texas: Museums, Art Centers, Alternative Spaces, and Nonprofit Galleries. University of Texas Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-292-71230-0.

- "Lake Jackson Elementary School". Brazosport ISD. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- "Source: Elisabet Ney Museum in Austin, Texas". Archived from the original on 2010-09-16. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

Additional sources

| Library resources about Elisabet Ney |

- Selected Bibliography, Elisabet Ney Museum Archived 2011-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Cutrer, Emily Fourmy, The Art of the Woman: The Life and Work of Elisabet Ney, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1988 (ISBN 0-8032-1438-3)

- Fortune, Jan and Jean Barton, Elisabet Ney, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1943

- Hendricks, Patricia D. and Becky Duval Reese, A Century of Sculpture in Texas: 1889–1989 (exhibition catalog), Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1989

- Little, Carol Morris, A Comprehensive Guide to Outdoor Sculpture in Texas, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1996 (ISBN 0-292-76034-5)

External links

Media related to Elisabet Ney at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Elisabet Ney at Wikimedia Commons- Elisabet Ney from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Official site of the Elisabet Ney Museum

- Elisabet Ney, Sculptor, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- "Lady Macbeth" Smithsonian American Art Museum

- Entry for Elisabet Ney on the Union List of Artist Names

- www.austintexas.gov/Elizabetney