Eliza McCardle Johnson

Eliza Johnson (née McCardle; October 4, 1810 – January 15, 1876) was the first lady of the United States from 1865 to 1869 as the wife of President Andrew Johnson. She also served as the second lady of the United States March 1865 until April 1865 when her husband was vice president. Johnson was relatively inactive as first lady, and she stayed out of public attention for the duration of her husband's presidency. She was the youngest first lady to wed, doing so at the age of 16.

Eliza McCardle Johnson | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, as engraved 1883 | |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869 | |

| President | Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Mary Todd Lincoln |

| Succeeded by | Julia Grant |

| Second Lady of the United States | |

| In role March 4, 1865 – April 15, 1865 | |

| Vice President | Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Ellen Hamlin |

| Succeeded by | Ellen Colfax |

| First Lady of Tennessee | |

| In role October 17, 1853 – November 3, 1857 | |

| Governor | Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Frances Owen |

| Succeeded by | Martha Mariah Travis |

| In role March 12, 1862 – March 4, 1865 | |

| Governor | Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Martha Mariah Travis |

| Succeeded by | Eliza O'Brien |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Eliza McCardle October 4, 1810 Telford, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | January 15, 1876 (aged 65) Greeneville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Resting place | Andrew Johnson National Cemetery Greeneville, Tennessee |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

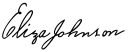

| Signature |  |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

16th Vice President of the United States

17th President of the United States

Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

Family

|

||

Johnson significantly contributed to her husband's early career, providing him with an education and encouraging him to strengthen his oratory skills and seek office. Johnson did not participate in the social aspects of politics, however, remaining at home while her husband took office. During the American Civil War, she was forced from her home for her family's Unionist loyalties. She was affected by tuberculosis throughout much of her life, and what activity she did choose to undertake was limited due to her health.

Johnson was briefly the second lady of the United States before becoming the first lady, as her husband was vice president until the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. After becoming the first lady, Johnson delegated the role's social duties to her daughter Martha Johnson Patterson. Though she only made two public appearances during her tenure as first lady, Johnson was a strong influence on her husband, and he would consult her regularly for advice. Johnson returned to her home of Greeneville, Tennessee with her family after leaving the White House, living a quiet retirement. She died six months after her husband and was buried beside him.

Early life and marriage

Eliza McCardle was born in Greeneville, Tennessee on October 4, 1810.[1]: 108 She was the only child of John McCardle, a cobbler and innkeeper, and Sarah Phillips.[2]: 116 The family moved to Warrensburg, Tennessee while McCardle was young, but they returned to Greeneville following her father's death.[3]: 191 McCardle was raised by her widowed mother, who financially supported her by weaving[4] and taught her to read and write.[2]: 116 McCardle attended school and received a basic education.[4] She is believed to have attended the Rhea Academy in Greenville.[5]: 203

McCardle met Andrew Johnson when his family moved to Greeneville in September 1826. She is said to have first seen him while talking amongst her friends, who began to tease her when she expressed her interest in the tailor's apprentice.[3]: 191 [6]: 131–132 McCardle and Johnson began courting almost immediately. The Johnsons left the city later that year, and the couple exchanged letters until he returned in 1827. They married on May 17, 1827.[2]: 117 Mordecai Lincoln, the cousin once removed of Abraham Lincoln, presided over the nuptials.[3]: 191–193 McCardle was 16-years-old, making her the youngest to marry of all the first ladies of the United States.[2]: 117 [7]: 231 After marrying, the couple moved into a two room house, where one of the rooms served as a tailor shop.[6]: 130

Eliza Johnson provided her husband much of his formal education,[2]: 117 though a common myth suggests that she even taught him to read and write.[3]: 193 They had five children together: Martha in 1828, Charles in 1830, Mary in 1832, Robert in 1834, and Frank in 1852. Once they began having children, much of Johnson's time was spent tending to the household while her husband operated his tailor shop.[2]: 117 In 1831, they purchased a larger home as well as a separate facility for the shop. They moved to a larger home again in 1851.[3]: 193

Politician's wife

Antebellum years

With Johnson's encouragement, her husband sought political office.[8] She played a large role in his early political career, assisting him in his education and his oratory skill.[7]: 231 As he attained higher political offices, Johnson avoided the social role associated with a politician's wife, instead tending to their home.[4] By this point, the household included eight or nine slaves.[3]: 194 It is unknown how Johnson felt about owning slaves.[7]: 232 As Johnson's children came of age, she enjoyed seeing her daughters seek husbands and start families of their own.[7]: 232 At the same time, her two older sons became a cause of stress as they were affected by alcoholism.[2]: 117

While at home, Johnson was responsible for managing the family's finances, including their many investments.[5]: 203 Though she did not accompany her husband when he traveled for his work, she supported him, providing encouragement and helping him with his speeches.[2]: 118 She suffered from tuberculosis, causing her to become infirm.[4] Her health improved and worsened in turn over the following years, but she never fully recovered. She eventually traveled to Washington, D.C. in 1860 with her sons, staying until the American Civil War began the following year.[3]: 194

American Civil War

During the war, Johnson became an advocate for Unionists that lived in the Confederate States of America.[2]: 118 She was forced to move after the Confederate States Army occupied the region,[4] leaving for her daughter Mary's farm after the Johnson home was captured by Confederate forces. While initially ordered to vacate the entire region within 36 hours in May 1862, she replied "I cannot comply with the requirement", and she was granted an additional five months.[5]: 204

Johnson eventually made the three week journey to Nashville, Tennessee, during which she was harassed and threatened for being the wife of a Unionist senator. The journey severely affected her health, but upon arriving in Nashville she reunited with her husband, who she had not seen in almost a year.[5]: 204 She later traveled north, passing through Confederate lines without escort, going to Ohio and Indiana to visit her children.[2]: 119 She returned to Nashville in May 1863. The Johnsons' eldest son, Charles, was killed later that year after being thrown from his horse.[3]: 195 She had little reprieve in Nashville, rarely seeing her husband, especially after he began campaigning in the 1864 presidential election.[7]: 233

Johnson's husband was sworn in as the Vice President of the United States in March 1865.[3]: 195 The following month, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, and her husband ascended to the presidency.[1]: 109 This had a severe emotional effect on her; in one letter, her daughter Martha described her as "almost deranged" with worry that her husband would be assassinated as well.[5]: 203 She also lamented the idea of becoming first lady, effectively rejecting the role.[1]: 109

First Lady of the United States

Johnson traveled to Washington with her surviving children, her son-in-law David T. Patterson, and her grandchildren.[2]: 119 They arrived on August 6, 1865.[3]: 196 After arriving, she chose a room on the second floor directly opposite the president's office.[6]: 129 Johnson was not able to serve effectively as first lady due to her poor health, and she remained largely confined to her bedroom, leaving the social chores to her daughter Martha.[3]: 196 Though she disliked being the president's wife, she enjoyed the fact that her entire family all lived together.[1]: 109

Johnson would receive her husband's guests at the White House,[1]: 109 but she appeared publicly as first lady on only two occasions: a celebration for Queen Emma of Hawaii in 1866 and a children's ball for the president's sixtieth birthday in 1868.[2]: 120 In both instances, she did not rise while receiving guests.[6]: 131 She also received many letters from the public while she was the first lady, often asking for political favors or access to the president. Her correspondences were managed by her daughter and the White House staff. Though she was not active publicly, Johnson was able to regularly engage in activities with her family with some assistance.[3]: 197

While living in the White House, Johnson often sewed and knitted, and she was frequently reading.[2]: 119–120 Each day, she would make her way through the White House residence, checking on her husband and the staff or spending time with her grandchildren.[3]: 198 She was close to the staff, treating both the white and black servants "as members of the household".[5]: 205 Johnson took up causes of her own, including a financial contribution to orphanages in Baltimore, Maryland,[3]: 198 and Charleston, South Carolina.[7]: 233 She also managed to travel while she was first lady, visiting nearby cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia in 1867.[3]: 198

Johnson did not have an active role in the politics of her husband's administration, though she gave him full support during his presidency, including during his impeachment.[4] She took an interest in the proceedings,[2]: 120 and the president would visit her each morning for her advice.[6]: 128 She held a strong influence over the president, and he regularly considered her advice.[5]: 205 She regularly monitored newspaper coverage of the presidency, clipping stories that she felt deserved the president's attention. She sorted them each day, showing him positive stories each night and then negative stories the following morning.[9]: 57

Johnson assisted the president with his speeches as she did in his previous political positions, and she worked to prevent the outbursts caused by his temper.[2]: 120 Her fear for her husband's safety persisted throughout his presidency, as the assassination of Abraham Lincoln was still in recent memory.[2]: 119 Despite her illness, she would still tend to her husband in certain areas, selecting his wardrobe for him and ensuring he was satisfied with the food provided for him.[6]: 129 Johnson disliked living in the White House, and she was glad when her husband's term ended.[6]: 131

Later life and death

The Johnsons returned to Greenville after leaving the White House in March 1869. Their son Robert took his own life the following month.[3]: 199 Johnson lived a quieter life after ending her tenure as first lady, often spending her time with her children and grandchildren.[7]: 234 She enjoyed a level of independence, sometimes traveling without her husband.[2]: 120–121 Her health declined by the time her husband was elected to the United States Senate in 1875, and she moved in with her daughter Mary. She was widowed shortly afterward on July 31, 1875.[3]: 199 Johnson's poor health and her grief prevented her from attending the funeral,[2]: 121 but she was appointed to execute his estate.[9]: 58 She died on January 15, 1876,[2]: 121 and she was buried beside her husband in Andrew Johnson National Cemetery.[7]: 234

Legacy

Johnson was one of the least active first ladies, playing little role in the political or social aspects of the White House. Her influence was that of an educator and adviser to her husband.[2]: 121 She did not meaningfully change the position of first lady during her tenure.[3]: 200 Historians generally describe Johnson as unassuming and unable to fulfill the role of first lady, but also as a capable intellectual partner for her husband. Though her husband's reputation declined considerably over the following century, Johnson's reputation as first lady remained largely unchanged.[7]: 234–235 Johnson's personal papers have been lost, in large part due to the Civil War.[7]: 230 Most primary documents associated with her are among her husband's papers.[3]: 200 In the 1982 Siena College Research Institute poll of historians, Johnson was ranked as the 21st of 42 first ladies.[10]

Johnson returned to the practice common among 19th century first ladies in which she allowed a younger surrogate to perform much of her duties, reestablishing the practice after the highly public tenure of her predecessor Mary Todd Lincoln.[11] She would be the last first lady to invoke illness in this fashion until Ida Saxton McKinley much later.[9]: 58 Johnson may have avoided public attention specifically because of the intense criticism levied at her predecessor and the potential for similar criticism given her husband's controversial presidency. She may also have feared that she lacked the social talents required of a hostess.[9]: 56 By the end of her tenure, she was described as "almost a myth" due to her limited public contact.[9]: 57

References

- Schneider, Dorothy; Schneider, Carl J. (2010). First Ladies: A Biographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Facts on File. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-1-4381-0815-5.

- Watson, Robert P. (2001). First Ladies of the United States. Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 116–121. doi:10.1515/9781626373532. ISBN 978-1-62637-353-2. S2CID 249333854.

- Young, Nancy Beck (1996). Gould, Lewis L. (ed.). American First Ladies: Their Lives and Their Legacy. Garland Publishing. pp. 191–201. ISBN 0-8153-1479-5.

- Diller, Daniel C.; Robertson, Stephen L. (2001). The Presidents, First Ladies, and Vice Presidents: White House Biographies, 1789–2001. CQ Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-56802-573-5.

- Anthony, Carl Sferrazza (1990). First Ladies: The Saga of the Presidents' Wives and Their Power, 1789-1961. William Morrow and Company. pp. 203–205. ISBN 9780688112721.

- Boller, Paul F. (1988). Presidential Wives. Oxford University Press. pp. 128–132.

- Sanfilippo, Pamela K. (2016). "Eliza McCardle Johnson and Julia Dent Grant". In Sibley, Katherine A. S. (ed.). A Companion to First Ladies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 230–235. ISBN 9781118732182.

- Longo, James McMurtry (2011). From Classroom to White House: The Presidents and First Ladies as Students and Teachers. McFarland. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7864-8846-9.

- Caroli, Betty (2010). First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Michelle Obama. Oxford University Press. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-0-19-539285-2.

- "Ranking America's First Ladies" (PDF). Siena College Research Institute. 2008-12-18.

- Beasley, Maurine H. (2005). First Ladies and the Press: The Unfinished Partnership of the Media Age. Northwestern University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780810123120.

External links

- Eliza McCardle Johnson at Find a Grave

- Eliza Johnson at 'History of American Women'

- The White House Web Site

- National First Ladies' Library Archived 2012-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Eliza Johnson at C-SPAN's First Ladies: Influence & Image

.jpg.webp)