Elrod Hendricks

Elrod Jerome "Ellie" Hendricks (December 22, 1940 – December 21, 2005) was a U.S. Virgin Islander professional baseball player and coach. He played in Major League Baseball as a catcher from 1968 through 1979, most notably as a member of the Baltimore Orioles dynasty that won three consecutive American League pennants from 1969 to 1971 and, won the World Series in 1970. He also played for the Chicago Cubs (1972) and New York Yankees (1976–1977). In 2001, he was inducted into the Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame.[1]

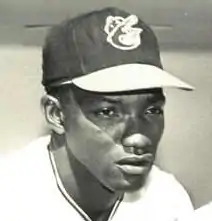

| Elrod Hendricks | |

|---|---|

Hendricks in 1968 | |

| Catcher | |

| Born: December 22, 1940 Charlotte Amalie, United States Virgin Islands | |

| Died: December 21, 2005 (aged 64) Glen Burnie, Maryland, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 13, 1968, for the Baltimore Orioles | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 19, 1979, for the Baltimore Orioles | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .220 |

| Home runs | 62 |

| Runs batted in | 230 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Biography

A native of Charlotte Amalie, United States Virgin Islands, Hendricks was selected by the Baltimore Orioles from the California Angels in the Rule 5 draft on November 28, 1967.[2] He was a superior defensive catcher and a very fine handler of pitchers on a usually strong Orioles rotation that included Mike Cuellar, Pat Dobson, Dave McNally, Jim Palmer and Tom Phoebus.

Hendricks spent most of his playing career with the Orioles, regularly with the winning teams of manager Earl Weaver. They went to three consecutive World Series from 1969–71, as Hendricks shared catching duties with Andy Etchebarren. Hendricks led all American League catchers in fielding percentage in 1969 and 1975.[3]

He was at bat in a pivotal play during the 1969 World Series. With the New York Mets leading 3–0 and two Orioles on base with two outs in the fourth inning of Game 3, Hendricks cracked a hard-hit line drive into the left-center field gap that most thought would go for extra bases, scoring two runs and putting the Orioles back in the game. But center fielder Tommie Agee, who was playing the left-handed Hendricks to pull in right-center, chased down the ball on a dead sprint, extending his left arm for a backhanded over-the-shoulder catch in the webbing of his glove.[4]

His most productive season came in 1970 with the World Champion Orioles, when he hit 12 home runs with 41 RBI. Hendricks went 4-for-11 (.364), hit a solo home run in Game 1, decided Game 2 with a two-run opposite-field double and had a total of four RBI to help Baltimore defeat the Cincinnati Reds in the 1970 World Series. He also appeared in the 1976 World Series for the Yankees against Cincinnati, returned to the Orioles as a bullpen coach following the 1977 season, and served as a player-coach in 1978 and 1979.

He was involved in the most controversial play of the 1970 World Series when the Cincinnati Reds were batting against the Orioles with one out and the score tied at three in the sixth inning of Game 1. With runners Tommy Helms at first base and Bernie Carbo at third, pinch hitter Ty Cline hit a Baltimore chop off Jim Palmer who, while running towards home plate, immediately signaled to Hendricks that Carbo was trying to score from third. Hendricks fielded the ball barehanded, spun around to his left and lunged at an oncoming Carbo in an attempt to tag him out, but collided with umpire Ken Burkhart who, while positioning himself to judge whether the batted ball was fair, accidentally blocked the runner's path to the plate. Carbo slid around Burkhart on the outside but missed touching home plate. With his back to the play and after being knocked down, Burkhart ruled Carbo out even though Hendricks made the tag with his mitt while holding the ball in his bare hand. Having not been properly tagged out, Carbo unknowingly stepped on the plate as he was arguing, but the play was dead once Burkhart made his call. Hendricks also had tied the game at 3–3 with a solo home run one inning earlier in the fifth.[5]

Hendricks also played briefly for the Chicago Cubs and New York Yankees, earning a World Series ring with the latter club in 1977. Playing for the Cubs on September 16, 1972, against the Mets at Wrigley Field, Hendricks received five bases on balls, equaling the league mark at that moment. He had been traded along with Ken Holtzman, Doyle Alexander, Grant Jackson and Jimmy Freeman from the Orioles to the Yankees for Rick Dempsey, Scott McGregor, Tippy Martinez, Rudy May and Dave Pagan at the trade deadline on June 15, 1976.[6]

Hendricks made the only pitching appearance in his MLB playing career in a 24–10 loss to the Toronto Blue Jays at Exhibition Stadium on June 26, 1978. He was the second consecutive position player used as a relief pitcher after Larry Harlow when he entered the game with two outs and the Orioles losing 24–6 in the fifth inning. He allowed only a hit and a walk over 21⁄3 scoreless innings.[7]

In 711 games played, including 658 with Baltimore, Hendricks was a .220 hitter with 62 home runs (still the all-time record for a United States Virgin Islands native) and 230 RBI. In nine postseason games, he had .273, 2 HR, 10 RBI. In 602 games as a catcher, Hendricks collected 2783 outs, 228 assists, 31 double plays, and committed just only 29 errors for a significant .990 fielding percentage.

Hendricks was a big star in Puerto Rico. He played for 17 seasons with the Cangrejeros de Santurce and occupies third place on the all-time list in homers with 105.

Coaching career

Hendricks became a fixture in Baltimore by holding the position of bullpen coach for 28 years, the longest coaching tenure in Orioles history. Hendricks was noted for consistently wearing shin guards in the Orioles bullpen, even when he wasn’t actually catching a potential relief pitcher.[8]

His contract was not renewed for that position as of October 2005, in part because he had a mild stroke in April. The 2005 season marked the 37th that Hendricks served in a Baltimore uniform as a player or coach, another club record. He also had the longest active coaching streak with one club among all major league coaches.

After his stroke, Hendricks was reassigned to another position within the organization, one that would enable the club to take advantage of his huge popularity within the Baltimore community; along with his loyalty to the "Oriole Way" and to the traditions of baseball, he was a tireless signer of pre-game autographs and a general good-will ambassador.

He was slated to be the host for the 2006 Baltimore Baseball Cruise aboard The Golden Princess.

Death

Elrod Hendricks died of a heart attack in Glen Burnie, Maryland, one day shy of his 65th birthday.[9]

The Orioles wore the number 44 on the sleeves of their jerseys in 2006, to honor Hendricks. Although the number has not been officially retired, no Oriole player has worn it since Hendricks died.

In 2007, St. Frances Academy in Baltimore started an annual baseball tournament in his name.

References

- "Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame at MLB.com". mlb.com. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Folkemer, Paul. "The Best Rule 5 Draft Picks in Baltimore Orioles History," PressBox Baltimore, December 2014". Archived from the original on 2018-07-04. Retrieved 2014-12-20.

- Baseball Digest, July 2001, P.86, Vol. 60, No. 7, ISSN 0005-609X

- Shaw, David (January 28, 2001). "Tommy Agee's passing stirs plenty of memories". SALISBURY POST. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Durso, Joseph. "Umpire Disputed," The New York Times, Sunday, October 11, 1970. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Chass, Murray. "Players Swap Memories of Yankees-Orioles 10-Player Trade", The New York Times, Sunday, June 15, 1986. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- "Blue Jays Rout Orioles By 24–10," The Associated Press (AP), Monday, June 26, 1978. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Connolly, Dan. "A character with class, Elrod never failed the fans". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- Goldstein, Richard (December 24, 2005). "Elrod Hendricks, Baltimore's Favorite Catcher and Coach, Dies at 64". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference

- Retrosheet

- Elrod Hendricks at the SABR Baseball Biography Project, by Rory Costello, Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- obituary