Baltimore Orioles

The Baltimore Orioles (also known as the O's) are an American professional baseball team based in Baltimore, Maryland. The Orioles compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member of the American League (AL) East division. As one of the American League's eight charter teams in 1901, the franchise spent its first year as a major league club in Milwaukee as the Milwaukee Brewers before moving to St. Louis to become the St. Louis Browns in 1902. After 52 years in St. Louis, the franchise was purchased in 1953 by a syndicate of Baltimore business and civic interests led by attorney and civic activist Clarence Miles and Mayor Thomas D'Alesandro Jr. The team's current owner is American trial lawyer Peter Angelos. The Orioles' home ballpark is Oriole Park at Camden Yards, which opened in 1992 in downtown Baltimore.[6][7]

| Baltimore Orioles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| Name | |||||

| |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (3) | |||||

| AL Pennants (7) | |||||

| AL East Division titles (10) | |||||

| Wild card berths (3) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Peter Angelos | ||||

| President | John P. Angelos (CEO) | ||||

| General manager | Mike Elias | ||||

| Manager | Brandon Hyde | ||||

The oriole is the official state bird of Maryland; the name has been used by several baseball clubs in the city, including another AL charter member franchise which moved to New York in 1903 and became the Yankees. Nicknames for the team include the "O's" and the "Birds".

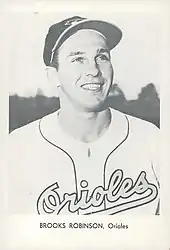

The franchise's first World Series appearance came in 1944 when the Browns lost to the St. Louis Cardinals. The Orioles went on to make six World Series appearances from 1966 to 1983, winning three in 1966, 1970, and 1983. This era of the club featured several future Hall of Famers who would later be inducted representing the Orioles, such as third baseman Brooks Robinson, outfielder Frank Robinson, starting pitcher Jim Palmer, first baseman Eddie Murray, shortstop Cal Ripken Jr., and manager Earl Weaver. The Orioles have won a total of ten division championships (1969, 1970, 1971, 1973, 1974, 1979, 1983, 1997, 2014, 2023), seven pennants (1944 while in St. Louis, 1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1979, 1983), and three wild card berths (1996, 2012, 2016). The franchise was the last charter member of the American League to win a pennant, and the last charter member to win a World Series.

After 14 consecutive losing seasons between 1998 and 2011, the team qualified for the postseason three times under manager Buck Showalter and general manager Dan Duquette, including a division title and advancement to the American League Championship Series for the first time in 17 years in 2014. Four years later, the Orioles lost 115 games, the most in franchise history.[8] The Orioles chose not to renew the expired contracts of Showalter and Duquette after the season, ending their respective tenures with Baltimore. The Orioles' current manager is Brandon Hyde, while Mike Elias serves as general manager and executive vice president. Two years after finishing 52-110 in 2021, the Orioles went 101-61 in 2023, en route to winning the AL East for the first time since 2014.

From 1901 through the end of 2023, the franchise's overall win–loss record is 9,029–10,013 (.474). Since moving to Baltimore in 1954, the Orioles have an overall win–loss record of 5,567–5,459 (.505) through the end of 2023.[9]

History

The modern Orioles franchise can trace its roots back to the original Milwaukee Brewers of the minor Western League, beginning in 1877, when the league reorganized. The Brewers were there when the Western League renamed itself the American League in 1900.

Milwaukee Brewers (1901)

At the end of the 1900 season, the American League removed itself from baseball's National Agreement (the formal understanding between the NL and the minor leagues). Two months later, the AL declared itself a competing major league. As a result of several franchise shifts, the Brewers were one of only two Western League teams that didn't fold, move or get kicked out of the league (the other being the Detroit Tigers). In its first game in the American League, the team lost to the Detroit Tigers 14–13 after surrendering a nine-run lead in the 9th inning.[10] To this day, it is a major league record for the biggest deficit overcome that late in the game.[11] In the first American League season in 1901, they finished last (eighth place) with a record of 48–89. During its lone Major League season, the team played at Lloyd Street Grounds, between 16th and 18th Streets in Milwaukee.

St. Louis Browns (1902–1953)

After one year in Milwaukee, the club relocated to St Louis, and for a while enjoyed some success, especially in the 1920s behind Hall of Fame first baseman George Sisler. However, the team's fortunes declined from then on, as playing success and gate receipts instead went increasingly to the Browns' own tenants at Sportsman's Park, the National League Cardinals, who became perennial NL contenders in the 1920s due to organizational innovations by team president Branch Rickey, a former player and manager for the Browns.

Through World War II, the Browns won only one pennant, in the 1944 season stocked with wartime replacement players, and lost to the Cardinals in the third and last World Series played entirely in one ballpark, (until 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

In 1953, with the Browns unable to afford even basic stadium upkeep and facing potential condemnation of the park by safety inspectors, owner Bill Veeck sold Sportsman's Park to the Cardinals and attempted to move the club back to Milwaukee, but this was vetoed by the other American League owners.

Instead, Veeck sold his franchise to a partnership of Baltimore businessmen. Because Veeck was unpopular with fellow American League owners, his leaving baseball was a condition for the AL owners to approve the move.[12][13]

Baltimore Orioles (since 1954)

The Miles-Krieger (Gunther Brewing Company)-Hoffberger group renamed their new team the Baltimore Orioles soon after taking control of the franchise. The nickname has a rich history in Baltimore, having been used by a National League club in the 1890s, an American League club (1901–02), and an International League club (AAA) from 1903 to 1953. The IL Orioles' most famous player was a local Baltimore product, hard-hitting left-handed pitcher Babe Ruth. When Oriole Park burned down in 1944, the team moved to a temporary home, Municipal Stadium, where they won the Junior World Series. Their large postseason crowds caught the attention of the major leagues, eventually leading to a new MLB franchise in Baltimore.[15]

First years in Baltimore (1954–1965)

The new AL Orioles took about six years to become competitive even after jettisoning most of the holdovers from St. Louis. Under the guidance of Paul Richards, who served as both field manager and general manager from 1955 to 1958 (the first man since John McGraw to hold both positions simultaneously),[16] the Orioles began a slow climb to respectability. While they posted a .500 record only once in their first five years (76–76 in 1957), they were a success at the gate. In their first season, for instance, they drew more than 1.06 million fans – more than five times what they had ever drawn in their tenures in Milwaukee and St. Louis. This came amid slight turnover in the ownership group. Miles served as team president for two years, then stepped down in favor of developer James Keelty. In turn, Keelty gave way in 1960 to financier Joe Iglehart.

By the early 1960s, stars such as Brooks Robinson, John "Boog" Powell, and Dave McNally were being developed by a strong farm system. The Orioles first made themselves heard in 1960, when they finished 89–65, good enough for second in the American League. While they were still eight games behind the Yankees, it was the first time they had been a factor in a pennant race that late in the season since 1944. It was also the first season of a 26-year stretch where the team would have only two losing seasons. Shortstop Ron Hansen was named AL Rookie of the Year, and first-year pitcher Chuck Estrada tied for the league lead in wins with 18, finishing second to Hansen in the Rookie of the Year balloting.

After the 1965 season, Hoffberger acquired controlling interest in the Orioles from Iglehart and installed himself as president. He had been serving as a silent partner over the past decade despite being the largest shareholder. Frank Cashen, advertising chief of Hoffberger's brewery, became executive vice-president.

Best years in Baltimore (1966–1983)

The Orioles farm system had begun to produce a number of high-quality players and coaches who formed the core of winning teams; from 1966 to 1983, the Orioles won three World Series titles (1966, 1970, and 1983), six American League pennants (1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1979, and 1983), and five of the first six American League East titles. The first of those titles, in 1966, made the Orioles the last of the eight teams that made up the American League from 1903 to 1960 to win a World Series.

During this time, the Orioles were known for playing baseball the Oriole Way, an organizational ethic best described by longtime farm hand and coach Cal Ripken, Sr.'s phrase "perfect practice makes perfect!" The Oriole Way was a belief that hard work, professionalism, and a strong understanding of fundamentals were the keys to success at the major league level. It was based on the belief that if every coach, at every level, taught the game the same way, the organization could produce "replacement parts" that could be substituted seamlessly into the big league club with little or no adjustment. This led to a run of success from 1966 to 1983 which saw the Orioles become the envy of the league, and the winningest team in baseball.

During this stretch, three different Orioles were named Most Valuable Player (Frank Robinson in 1966, Boog Powell in 1970, and Cal Ripken Jr. in 1983), four Oriole pitchers combined for six Cy Young Awards (Mike Cuellar in 1969, Jim Palmer in 1973, 1975, and 1976, Mike Flanagan in 1979, and Steve Stone in 1980), and three players were named Rookie of the Year (Al Bumbry in 1973, Eddie Murray in 1977, and Cal Ripken Jr. in 1982).

It was also during this time that the Orioles severed their last remaining financial link to their era in St. Louis. In 1979, Hoffberger sold the Orioles to his longtime friend, Washington attorney Edward Bennett Williams. As part of the deal, Williams bought the publicly traded shares Donald Barnes had issued in 1936 while the team was still in St. Louis, making the franchise privately held once again and severing one of the few remaining links with the Orioles' past in St. Louis.

During this rise to prominence, Weaver Ball came into vogue. Named for fiery manager Earl Weaver, it was defined by the Oriole trifecta of "Pitching, Defense, and the Three-Run Home Run." When an Oriole GM was told by a reporter that Weaver, as the skipper of a very talented team, was a "push-button manager", he replied, "Earl built the machine and installed all the buttons!"

As Frank and Brooks Robinson grew older, newer stars emerged, including multiple Cy Young Award winner Jim Palmer and switch-hitting first baseman Eddie Murray. With the decline and eventual departure of two other professional sports teams in the area, the NFL's Baltimore Colts and baseball's Washington Senators, the Orioles' excellence paid off at the gate, as the team cultivated a large and rabid fan base at Memorial Stadium.

Final seasons at Memorial Stadium (1984–1991)

After winning the 1983 World Series,[17] the Orioles spent the next five years in steady decline, finishing 1986 in last place for the first time since the franchise moved to Baltimore. The team hit bottom in 1988 when it started the season 0–21, en route to 107 losses and the worst record in the majors that year. The "Why Not?" Orioles surprised the baseball world the following year by spending most of the summer in first place until September when the Toronto Blue Jays overtook them and seized the AL East title on the final weekend of the regular season. The next two years were spent below the .500 mark, highlighted only by Cal Ripken Jr. winning his second AL MVP Award in 1991. The Orioles said goodbye to Memorial Stadium, the team's home for 38 years, at the end of the 1991 campaign.

Camden Yards opens and Ripken's record (1992–1995)

Opening to much fanfare in 1992, Oriole Park at Camden Yards was an instant success, inspiring other retro-style major league ballparks in the next decades. The stadium was the site of the 1993 All-Star Game. The Orioles returned to contention in the first two seasons at Camden Yards, only to finish in third place both times.

In 1993, with then-owner Eli Jacobs forced to divest himself of the franchise, Baltimore-based attorney Peter Angelos, along with the ownership syndicate he headed, was awarded the Orioles in bankruptcy court in New York City, returning the team to local ownership for the first time since 1979. Angelos' partners included author Tom Clancy and comic book distributor Steve Geppi.[18] The Orioles, who spent all of 1994 chasing the New York Yankees, occupied second place in the new five-team AL East when the players strike, which began on August 11, forced the eventual cancellation of the season.[19]

The labor impasse would continue into the spring of 1995. Almost all the major league clubs held spring training using replacement players, with the intention of beginning the season with them. The Orioles, whose owner was a labor union lawyer, were the lone dissenters against creating an ersatz team, choosing instead to sit out spring training and possibly the entire season. Had they fielded a substitute team, Cal Ripken Jr.'s consecutive games streak would have been jeopardized. The replacements questions became moot when the strike was finally settled. The Ripken countdown resumed once the season began. Ripken finally broke Lou Gehrig's consecutive games streak of 2,130 games in a nationally televised game against the California Angels on September 6.[20] This was later voted the all-time baseball moment of the 20th century by fans from around the country in 1999. Ripken finished his streak with 2,632 straight games, finally sitting on September 20, 1998, the Orioles final home game of the season against the Yankees at Camden Yards.

Playoff years (1996–1997)

Before the 1996 season, Angelos hired Pat Gillick as general manager. Given the green light to spend heavily on established talent, Gillick signed several premium players like B. J. Surhoff, Randy Myers, David Wells and Roberto Alomar. Under new manager Davey Johnson and on the strength of a then-major league record 257 home runs in a single season, the Orioles returned to the playoffs after a 12-year absence by clinching the AL wild card berth. Alomar set off a firestorm in September when he spat into home plate umpire John Hirschbeck's face during an argument in Toronto. He was later suspended for the first five games of the 1997 season, even though most wanted him banned from the postseason. After dethroning the defending American League champion Cleveland Indians 3–1 in the Division Series, the Orioles fell to the Yankees 4–1 in an ALCS notable for right field umpire Rich Garcia's failure to call fan interference in the first game of the series, when 12-year-old Yankee fan Jeffrey Maier reached over the outfield wall to catch an in-play ball, which was scored as a home run for Derek Jeter, tying the game at 4–4 in the eighth inning. Absent Maier's interference, it appeared as if the ball might have been off the wall or caught by right fielder Tony Tarasco. The Yankees went on to win the game in extra innings on an ensuing walk-off home run by Bernie Williams.

The Orioles went "wire-to-wire" (first place from start to finish) in winning the AL East title in 1997. After eliminating the Seattle Mariners 3–1 in the Division Series, the team lost again in the ALCS, this time to the underdog Indians 4–2, with each Oriole loss by only a run. Johnson resigned as manager after the season, largely due to a spat with Angelos concerning Alomar's fine for missing a team function being donated to Johnson's wife's charity.[21] Pitching coach Ray Miller replaced Johnson.

Downturn (1998–2006)

With Miller at the helm, the Orioles found themselves not only out of the playoffs, but also with a losing season. When Gillick's contract expired in 1998, it was not renewed. Angelos brought in Frank Wren to take over as GM. The Orioles added volatile slugger Albert Belle, but the team's woes continued in the 1999 season, with stars like Rafael Palmeiro, Roberto Alomar, and Eric Davis leaving in free agency. After a second straight losing season, Angelos fired both Miller and Wren. He named Syd Thrift the new GM and brought in former Cleveland manager Mike Hargrove. In a rare event on March 28, 1999, the Orioles staged an exhibition series against the Cuban national team in Havana. The Orioles won the game 3–2 in 11 innings. They were the first Major League team to play in Cuba since 1959, when the Los Angeles Dodgers faced the Orioles in an exhibition. The Cuban team visited Baltimore in May 1999 (winning 10–6).

The first decade of the 21st century saw the Orioles struggle due to the combination of lackluster play on the team's part, a string of ineffective management, and the ascent of New York and Boston to the top of the game – each rival having a clear advantage in financial flexibility due to their larger media market size. Further complicating the situation for the Orioles was the relocation of the National League's Montreal Expos franchise to nearby Washington, D.C., in 2004. Orioles owner Peter Angelos demanded compensation from Major League Baseball, as the new Washington Nationals threatened to carve into the Orioles fan base and television dollars. However, there was some hope that having competition in the larger Baltimore-Washington metro market would spur the Orioles to field a better product to compete for fans with the Nationals.

Rebuilding years & arrival of Buck Showalter (2007–2011)

A new President of Baseball of Operations named Andy MacPhail was brought in about halfway through the 2007 season. MacPhail spent the remainder of the 2007 season assessing the talent level of the Orioles, and determined that significant steps needed to be made if the Orioles were ever to be a contender again in the American League East. He completed two blockbuster trades during the next off-season, each sending a premium player away in return for five prospects (or younger less expensive players). Tejada, who had hit .296 with 18 HR and 81 RBI in 2007, went to the Houston Astros in exchange for outfielder Luke Scott, pitchers Matt Albers, Troy Patton, and Dennis Sarfate, and third baseman Mike Costanzo. Also, the newly designated ace of the Orioles rotation Érik Bédard, who went 13–5 with a 3.16 ERA in 2007 with 221 strikeouts, was sent to the Seattle Mariners in exchange for top outfield prospect Adam Jones, left-handed pitcher George Sherrill, and three minor league pitchers Chris Tillman, Kam Mickolio, and Tony Butler. The Bedard trade in particular would go down as one of the most lop-sided and successful trades in the history of the franchise.

While MacPhail would find success in most of his trades made for the Orioles over the long-term, the veteran stop acquisitions that he would make would not often pan out, and as a result, the team would never finish higher than 4th place in the AL East, or with more than 69 wins, while MacPhail was in charge. Although some of his free agent signings would have positive contributions (such as reliever Koji Uehara), most gave mediocre returns, at best. In particular, the Orioles never managed to cobble together a successful pitching staff during this time. Their most consistent starting pitcher from 2008 to 2011 was the late bloomer Jeremy Guthrie who was named the Opening Day starter in 3 of the 4 seasons and had a cumulative 4.12 ERA during this stretch.

Following Davey Johnson's dismissal after the 1997 playoff season, Orioles ownership struggled to find a manager that they liked, and this time period was no exception. Dave Trembley was brought on as an interim manager in June 2007, and had the interim tag removed later that year. Trembley was at the helm again in 2008 and 2009 but was never able to lead the team out of the cellar in the AL East. After starting the 2010 season a dismal 15–39, Dave Trembley was fired and third base coach Juan Samuel was named the interim manager. The Orioles were seeking a more permanent solution at manager as the 2010 season continued to unfold, and two-time AL Manager of the Year Buck Showalter was eventually hired in July 2010. The Orioles went 34–23 after Buck took over, foreshadowing that a brighter future might be on the horizon, and giving Orioles fans renewed hope and optimism for the team's future.

The Orioles made some aggressive moves to improve the team in 2011 in the hopes of securing their first playoff berth since 1997. Andy MacPhail completed trades to bring in established veterans like Mark Reynolds and J. J. Hardy from the Diamondbacks and Twins, respectively. Veteran free agents Derrek Lee and Vladimir Guerrero were also brought in to help improve the offense. At the 2011 trade deadline, fan favorite Koji Uehara was sent to the Texas Rangers in exchange for Chris Davis and Tommy Hunter, a move that would not pay immediate dividends, but would be crucial to the team's later success. While these moves had varying impacts, the Orioles did score 95 more runs in 2011 than they had the previous year. The team still finished last in the AL East due to the utter failures of the team's pitching staff. Brian Matusz compiled one of the highest single-season ERAs in MLB history (10.69 over 12 starts) and every pitcher who started a game for the Orioles in 2011 ended the season with an ERA of 4.50 or higher except for Jeremy Guthrie. The Orioles finished 30th out of 30 MLB teams that year with a 4.89 team ERA. Andy MacPhail's contract was not renewed in October 2011 and a search for a new GM began. After a public interview process where several candidates declined to take the position, ex-GM Dan Duquette was brought in to serve as the Executive Vice-President of Baseball Operations.

Return to success under Showalter (2012–2016)

Duquette wasted no time in overhauling the Orioles roster, especially the MLB-worst pitching staff. He traded fan favorite Jeremy Guthrie to the Colorado Rockies in exchange for Jason Hammel. He brought in new free agent starting pitcher Wei-Yin Chen from the Nippon Professional Baseball league, and Miguel González was signed as a minor league free agent. Nate McLouth was signed to a minor league deal in June 2012 and would prove to make a significant impact down the stretch. This year also marked the debut of the much hyped prospect Manny Machado.

.jpg.webp)

The Orioles won 93 games in 2012 (after winning 69 in the previous year) thanks in large part to a 29–9 record in one-run games, and a 16–2 record in extra inning games. The difference between this Orioles bullpen and bullpens past was like night and day, led by Jim Johnson and his 51 saves. He finished with a 2.49 ERA that season with Darren O'Day, Luis Ayala, Pedro Strop, and Troy Patton all finishing as well with ERAs under 3.00. Experts were amazed as the team continued to outperform expectations, but regression never came that year. They battled with the New York Yankees for first place in the AL East up until September, and would earn their first playoff berth in 15 years by winning the second wildcard spot in the American League.

In the 'sudden death' wildcard game against the Texas Rangers, Joe Saunders (acquired in August of that year in exchange for Matt Lindstrom) defeated Yu Darvish to help the Orioles advance to the divisional round, where they faced a familiar opponent, the Yankees. The Orioles forced the series to go five games (losing games 1 and 3 of the series, while winning 2 and 4), but CC Sabathia outpitched the Orioles Jason Hammel in Game 5 and the Orioles were eliminated from the playoffs.

While the Orioles would ultimately miss the playoffs in 2013, they finished with a record of 85–77, tying the Yankees for third place in the AL East. By posting winning records in 2012 and 2013, the Orioles achieved the feat of back-to-back winning seasons for the first time since 1996 and 1997.

On September 16, 2014, the Orioles clinched the division for the first time since 1997 with a win against the Toronto Blue Jays as well as making it back to the postseason for the second time in three years. The Orioles finished the 2014 season with a 96–66 record and went on to sweep the Detroit Tigers in the ALDS. The O's were then in turn swept by the Kansas City Royals in the ALCS.

Out of an abundance of caution, the Baltimore Orioles announced the postponement of the April 27 and 28 games in 2015 against the Chicago White Sox following violent riots in West Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray.[22] Following the announcement of the second postponement, the Orioles also announced that the third game in the series scheduled for Wednesday, April 29 was to be closed to the public and would be televised only,[23] apparently the first time in 145 years of Major League Baseball that a game had no spectators and breaking the previous 131-year-old record for lowest paid attendance to an official game (the previous record being 6.) [24] The Orioles beat the White Sox, 8–2.[25] The Orioles said the make-up games would be played Thursday, May 28, as a double-header. In addition, the weekend games against the Tampa Bay Rays was moved to the Rays' home stadium in St. Petersburg where Baltimore played as the home team.[26][27]

Downfall and final years under Showalter (2017–2018)

Despite the 2016 season being another above .500 season for the Orioles; they would fail to win their division, but were able to secure a Wild card spot. However, they would lose against the Toronto Blue Jays in the AL Wild Card game. This was the last postseason appearance for Baltimore until 2023. In 2017, the Orioles started with a modest 22–10 record. Despite early season success, the Orioles suffered their first losing season since 2011. The Orioles would suffer one of Major League Baseball's worst seasons in 2018, en route to going 47–115. 2018 proved to be general manager Duquette and Showalter's final season in Baltimore, as their contracts were not renewed after the season.

Brandon Hyde era (2019–present)

The Orioles began their rebuild by trading away fan favorites Manny Machado, Zach Britton, Jonathan Schoop, Brad Brach, Kevin Gausman, and Darren O'Day in July 2018. In 2019, the Orioles finished 54–108, which was the second Orioles team to surpass the 1988 Orioles team's losses. In 2020, the Orioles experienced an upside in their rebuild, as they finished 25–35 in a season shortened by the COVID-19 pandemic, their best finish since 2017. In 2021, the Orioles experienced two different losing streaks of at least 14, en route to a 52–110 finish. 2021 was their third 110-loss season in team history. Their first was 1939 when they were known as the St. Louis Browns, the second was in 2018 as the Baltimore Orioles.

On June 9, 2022, Louis Angelos sued his brother, Orioles chairman and CEO John P. Angelos, and mother Georgia Angelos in Baltimore County Circuit Court.[28][29] Louis Angelos claims that their father intended for the brothers and their mother to share control of the team. The lawsuit states the elder Angelos collapsed in 2017 due to heart problems and established a trust with his wife and sons as co-trustees. Louis Angelos is seeking to have his brother and mother removed as co-trustees of the trust that controls the Orioles and removed as co-agents of Peter Angelos' power of attorney.

The suit claims Georgia Angelos wants to sell the team and an advisor attempted to negotiate a sale in 2020 but John Angelos vetoed a potential deal. The suit claims Angelos unilaterally fired long-time employees loyal to his father, including former center fielder Brady Anderson, the longtime special assistant to the executive vice president for baseball operations. The suit claims John Angelos transferred tens of millions of dollars worth of property out of his father's law firm and into a limited liability company controlled by his personal attorney.[28]

In separate statements released by the team, Georgia and John Angelos refuted the claims.[30][31]

In the event of any sale, Major League Baseball has reportedly encouraged Cal Ripken Jr to be part of any incoming ownership group that may take control of the team.[32]

In April 2023, the Orioles went 19–9, setting a franchise record for wins in the month of April.[33] By August 2023, the Orioles, led by a core of first-and-second-year players Adley Rutschman, Gunnar Henderson, Félix Bautista and Kyle Bradish, were in first place in the division and described in The Athletic as "young, fun and arguably the best story in baseball." Much of their good will was overshadowed, however, when it was reported that play-by-play announcer Kevin Brown had been suspended indefinitely by the Orioles for his pregame remarks on MASN, the team-owned network, two weeks earlier. During a "seemingly benign" introduction to a series against the Tampa Bay Rays, Brown observed that the team had struggled to win a series in Tampa in the past several seasons. It was described in The Athletic as a "petty" move by John Angelos, "the only person [in the organization] with enough power that no one dare question the validity of anything he says and does, no matter how foolish it is."[34] Several broadcasters came to Brown's defense after the news broke. Gary Cohen said the team had "draped itself in utter humiliation" and Michael Kay said the suspension made "the Orioles look so small and insignificant and minor league."[35]

Regular season home attendance

.jpg.webp) The facade of Memorial Stadium

The facade of Memorial Stadium Baltimore Memorial Stadium in 1991

Baltimore Memorial Stadium in 1991 Camden Yards in 2021

Camden Yards in 2021

Memorial Stadium

|

Oriole Park at Camden Yards

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Logos and uniforms

The Orioles' home uniform is white with the word "Orioles" written across the chest. The road uniform is gray with the word "Baltimore" written across the chest. This style, with noticeable changes in the script, striping and materials, has been worn for much of the team's history, but with a few exceptions:

- In 1954, 1989–94 (road) and 1995–2003 (home), the scripted word "Orioles" and block letters are rendered in black with orange trim. The 1995–2003 style featured orange numbers in front but black letters in the back.

- From 1963 to 1965, the home uniforms featured "Orioles" in block lettering instead of the more familiar cursive script style. It was also rendered in black with orange trim.

- The underline below the word "Orioles" disappeared from 1966 to 1988.

- Road uniforms bore the team name from 1954 to 1955 and from 1973 to 2008.

- Extra white trim was added to the road and alternate uniforms from 1995 to 2000.

- Sleeveless home alternate uniforms were used in the 1968 and 1969 seasons.

- Player names were added to the uniforms in 1966, but the home uniforms originally featured black block letters. It would not match the road uniform lettering until 1971, which were orange with black trim.

A long campaign of several decades was waged by numerous fans and sportswriters to return the name of the city to the "away" jerseys which was used since the 1950s and had been formerly dropped during the 1970s era of Edward Bennett Williams when the ownership was continuing to market the team also to fans in the nation's capital region after the moving of the former Washington Senators in 1971. After several decades, approximately 20% of the team's attendance came from the metro Washington area.

An alternate uniform is black with the word "Orioles" written across the chest. They first wore black uniforms in the 1993 season and continue to do so since; the current style with the letters lacking additional trim was first used in 2000. The Orioles wear their black alternate jerseys for Friday night games with the alternate "O's" cap (first introduced in 2005), whether at home or on the road; the regular batting helmet is still used with this uniform. In 2017, the Orioles began to use their batting practice caps for select games with the black uniforms. The aforementioned caps resemble their regular road caps save for the black bill. Occasionally, the Orioles would also wear the black alternates on other days of the week, often pairing them with the home or road "cartoon bird" caps. After the "City Connect" uniforms became the team's Friday home uniform (see below), the black alternates were only used on Friday road games and on home games depending on the preference of the starting pitcher.

The Orioles also wore orange alternate uniforms at various points in their history. The orange alternates were first used in the 1971 season and were paired with orange pants, but these lasted only two seasons. The second orange uniform, which was a pullover style, was worn from 1975 to 1987, but were not worn at all in the 1983, 1985 and 1986 seasons. A third orange uniform was used from 1988 to 1992, returning to the button-down style. In 2012, the Orioles brought back the orange uniforms as a second alternate uniform; the team currently wears them on Saturdays at home or on the road, though they've also worn them on other days of the week either due to pitcher's preference or a previously postponed contest.

The Orioles' cap design have alternated between the team's iconic "cartoon bird" logo and the full-bodied bird logo. Initially, the caps had the full-bodied bird logo between 1954 and 1965, alternating between an all-black cap and an orange-brimmed black cap. They also wore a black cap with an orange block-letter "B" for part of the 1963 season. The "cartoon bird" was first used in 1966, and with minor tweaks, was prominently featured on the team's caps until 1988. Initially, the Orioles kept the orange-brimmed black cap with the "cartoon bird", but switched to a white-paneled black cap with orange brim in 1975. Also that same year, they wore orange-paneled black caps to pair with the orange alternates, but these lasted only two seasons.

In 1989, the full-bodied bird logo returned along with the all-black cap, with a few tweaks along the way. Initially the cap was used regardless of home or road games, but in 2002 the caps were worn only on the road until 2008. An orange-brimmed variety was also introduced in 1995. Initially exclusive to the team's black uniforms, this style became the home cap in 2002 and became the team's regular cap (home or away) from 2009 to 2011.

In 2012, the Orioles brought back a modernized version of the "cartoon bird" along with the white-paneled and orange-brimmed black cap for home games and the orange-brimmed black cap for road games.

In 2013, ESPN ran a "Battle of the Uniforms" contest between all 30 Major League clubs. Despite using a ranking system that had the Orioles as a #13 seed, the Birds beat the #1 seed Cardinals in the championship round.[37]

In 2023, the Orioles introduced a new City Connect jersey, inspired by the art and culture of Baltimore and its neighborhoods.[38]

Radio and television coverage

Radio

In Baltimore, Orioles radio broadcasts can be heard on WBAL-AM and WIYY, both owned by Hearst Television. Geoff Arnold, Melanie Newman, Brett Hollander, Scott Garceau and Kevin Brown alternate as play-by-play announcers. WBAL feeds the games to a network of 36 stations, covering Washington, D.C., and all or portions of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, West Virginia, and North Carolina.

This is WBAL's fourth stint as the Orioles flagship. WBAL has carried Orioles games for most of the team's time in Baltimore. Prior to WBAL and WIYY, Orioles games were broadcast locally on WJZ-FM from 2015 to 2021. WJZ had earlier carried broadcasts from 2007 to 2010.

Six former Orioles franchise radio announcers have received the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award for excellence in broadcasting: Chuck Thompson (who was also the voice of the old NFL Baltimore Colts); Jon Miller (now with the San Francisco Giants); Ernie Harwell, Herb Carneal; Bob Murphy and Harry Caray (as a St. Louis Browns announcer in the 1940s[39]).

Other former Baltimore announcers include Josh Lewin (currently with New York Mets), Bill O'Donnell, Tom Marr, Scott Garceau (returned in 2020 season), Mel Proctor, Michael Reghi, former major league catcher Buck Martinez (now Toronto Blue Jays play-by-play), and former Oriole players including Brooks Robinson, pitcher Mike Flanagan and outfielder John Lowenstein. In 1991, the Orioles experimented with longtime TV writer/producer Ken Levine as a play-by-play broadcaster. Levine was best noted for his work on TV shows such as Cheers and M*A*S*H, but lasted only one season in the Orioles broadcast booth.

Television

MASN, co-owned by the Orioles and the Washington Nationals, is the team's exclusive television broadcaster. MASN airs almost the entire slate of regular season games. Some exceptions include Saturday games on either Fox (via its Baltimore affiliate, WBFF) or Fox Sports 1, or Sunday Night Baseball on ESPN. Many MASN telecasts in conflict with Nationals' game telecasts air on an alternate MASN2 feed.

Veteran sportscaster Gary Thorne served as lead television announcer from 2007 to 2019, with Jim Hunter as his backup along with Hall of Fame member and former Orioles pitcher Jim Palmer and former Oriole infielder Mike Bordick as color analysts, who almost always work separately. In 2020, Thorne and Palmer were removed from the television booth due to COVID-19 concerns, and replaced with Scott Garceau. In 2021, MASN let go Thorne, Hunter, analysts Mike Bordick and Rick Dempsey, and studio host Tom Davis, and added Ben McDonald as a secondary analyst.[40][41][42] Starting in 2022, Kevin Brown became the primary TV play-by-play announcer, with Garceau, Arnold or Newman the backups.[43]

The Orioles severed their ties with Comcast SportsNet Mid-Atlantic (now NBC Sports Washington) at the end of the 2006 season in favor of MASN, a joint venture with the Washington Nationals. It had been the Orioles' cable partner since 1984, when it was known as Home Team Sports. The Orioles and the Washington Nationals have been in a dispute since the early 2010s, MASN is owned by both teams with the Orioles holding an 80% stake. The dispute which is ongoing as of October 2020 contends that the Nationals deserves a greater fee from MASN due to the team's recent success and market growth. When fees paid to each team were first negotiated, both teams were paid the same fees.[44]

WJZ-TV was the Orioles' broadcast TV home, completing its latest stint from 1994 through 2017. Since MASN acquired rights in 2007, its coverage was simulcast on WJZ-TV under the branding "MASN on WJZ 13". MASN elected not to syndicate any Orioles or Washington Nationals games to broadcast television for the 2018 season, marking the first time since the Orioles' arrival that their games are not on local broadcast television.[45]

Previously, WJZ-TV carried the team from their arrival in Baltimore in 1954 through 1978. In the first four seasons, WJZ-TV shared coverage with Baltimore's other two stations, WMAR-TV and WBAL-TV. The games moved to WMAR from 1979 through 1993 before returning to WJZ-TV. From 1994 to 2009, some Orioles games aired on WNUV.

Musical traditions

"O!"

Since its introduction at games by the "Roar from 34", led by Wild Bill Hagy and others, in the late 1970s, it has been a tradition at Orioles games for fans to yell out the "Oh" in the line "Oh, say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave" in "The Star-Spangled Banner".[46] "The Star-Spangled Banner" has special meaning to Baltimore historically, as it was written during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812 by Francis Scott Key, a Baltimorean.

The tradition is often carried out at other sporting events, both professional and amateur, and even sometimes at non-sporting events where the anthem is played, throughout the Baltimore/Washington area and beyond. Fans in Norfolk, Virginia, chanted "O!" even before the Tides became an Orioles affiliate. The practice caught some attention in the spring of 2005, when fans performed the "O!" cry at Washington Nationals games at RFK Stadium. The "O!" chant is also common at sporting events for the various Maryland Terrapins teams at the University of Maryland, College Park. At Cal Ripken Jr.'s induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the crowd, composed mostly of Orioles fans, carried out the "O!" tradition during Tony Gwynn's daughter's rendition of "The Star-Spangled Banner". Additionally, a faint but audible "O!" could be heard on the television broadcast of Barack Obama's pre-inaugural visit to Baltimore as the national anthem played before his entrance. A resounding "O!" bellowed from the nearly 30,000 Ravens fans who attended the November 21, 2010, away game at the Carolina Panthers' Bank of America Stadium in Charlotte, North Carolina.[47] A similar loud "O!" was heard from fans attending Super Bowl XLVII between the Baltimore Ravens and the San Francisco 49ers.[48] The "O!" chant was also heard during the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, when Baltimore native Michael Phelps received his gold medal for the 4 × 200 m freestyle on August 9, 2016.[49]

In recent years, when the Orioles host the Toronto Blue Jays, fans have begun to shout out the multiple instances of the word "O" in "O Canada". Washington Capitals fans will do the same when they play one of the NHL's Canadian teams.

"Thank God I'm a Country Boy"

It has been an Orioles tradition since 1975 to play John Denver's "Thank God I'm a Country Boy" during the seventh-inning stretch.

In the edition of July 5, 2007, of Baltimore's weekly sports publication Press Box, an article by Mike Gibbons covered the apocryphal details of how this tradition came to be.[50] During "Thank God I'm a Country Boy", Charlie Zill, then an usher, would put on overalls, a straw hat, and false teeth and dance around the club level section (244) that he tended to. He also has an orange violin that spins for the fiddle solos. He went by the name Zillbilly and had done the skit from the 1999 season until shortly before he died in early 2013. Of course, that does nothing to explain why the Orioles' Audio staff began playing the song during every game's seventh inning stretch beginning in August, 1975.

In reality, the song was tremendously successful nationwide, topping the Billboard Top 100 for one week in 1975, and was played in stadiums across the country. The Orioles were chasing the Red Sox for the American League East Division title and incorporated numerous "good luck charms." After an inspiring comeback win, Oriole staff began playing this song at the seventh-inning stretch of every home game as one of the good-luck charms, beginning in August.

During a nationally televised game on September 20, 1997, Denver himself danced to the song atop the Orioles' dugout, one of his final public appearances before dying in a plane crash three weeks later.[51]

"Orioles Magic" and other songs

Songs from notable games in the team's history include "One Moment in Time" for Cal Ripken's record-breaking game in 1995, as well as the theme from Pearl Harbor, "There You'll Be" by Faith Hill, during his final game in 2001. The theme from Field of Dreams was played at the last game at Memorial Stadium in 1991, and the song "Magic to Do" from the stage musical Pippin was used that season to commemorate "Orioles Magic" on 33rd Street. During the Orioles' heyday in the 1970s, a club song, appropriately titled "Orioles Magic (Feel It Happen)", was composed by Walt Woodward,[52] and played when the team ran out until Opening Day of 2008. Since then, the song (a favorite among all fans, who appreciated its references to Wild Bill Hagy and Earl Weaver) is played (along with a video featuring several Orioles stars performing the song) only after wins. Seven Nation Army is played as a hype song while the fans chant the signature bass riff as a rally cry during key moments of a game or after a walk-off hit.

The First Army Band

During the Orioles' final homestand of the season, it is a tradition to display a replica of the 15-star, 15-stripe American flag at Camden Yards. Prior to 1992, the 15-star, 15-stripe flag flew from Memorial Stadium's center-field flagpole in place of the 50-star, 13-stripe flag during the final homestand. Since the move to Camden Yards, the former flag has been displayed on the batters' eye. During the Orioles' final home game of the season, The United States Army Field Band from Fort Meade performs the National Anthem prior to the start of the game. The Band has also played the National Anthem at the finales of three World Series in which the Orioles played: 1970, 1971 and 1979. They are introduced as the "First Army Band" during the pregame ceremonies.

PA announcer

For 23 years, Rex Barney was the PA announcer for the Orioles. His voice became a fixture of both Memorial Stadium and Camden Yards, and his expression "Give that fan a contract", uttered whenever a fan caught a foul ball, was one of his trademarks – the other being his distinct "Thank Yooooou ..." following every announcement. (He was also known on occasion to say "Give that fan an error" after a dropped foul ball.) Barney died on August 12, 1997, and in his honor that night's game at Camden Yards against the Oakland Athletics was held without a public–address announcer.[53]

Barney was replaced as Camden Yards' PA announcer by Dave McGowan, who held the position until December 2011.

Lifelong Orioles fan and former MLB Fan Cave resident Ryan Wagner soon took over as the PA announcer. He was chosen out of a field of more than 670 applicants in the 2011–12 offseason.[54]

As of the 2022 season, Adrienne Roberson is the current Orioles PA announcer.

Postseason appearances

Of the eight original American League teams, the Orioles were the last of the eight to win the World Series, doing so in 1966 with its four–game sweep of the heavily favored Los Angeles Dodgers. When the Orioles were the St. Louis Browns, they played in only one World Series, the 1944 matchup against their Sportsman's Park tenants, the Cardinals. The Orioles won the first-ever American League Championship Series in 1969, and in 2012 the Orioles beat the Texas Rangers in the inaugural American League Wild Card game, where for the first time two Wild Card teams faced each other during postseason play.

| Year | Wild Card Game | ALDS | ALCS | World Series | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944[A] | Not played | St. Louis Cardinals | L | |||||

| 1966[B] | Not played | Los Angeles Dodgers | W | |||||

| 1969 | Not played | Minnesota Twins | W | New York Mets | L | |||

| 1970 | Not played | Minnesota Twins | W | Cincinnati Reds | W | |||

| 1971 | Not played | Oakland Athletics | W | Pittsburgh Pirates | L | |||

| 1973 | Not played | Oakland Athletics | L | |||||

| 1974 | Not played | Oakland Athletics | L | |||||

| 1979 | Not played | California Angels | W | Pittsburgh Pirates | L | |||

| 1983 | Not played | Chicago White Sox | W | Philadelphia Phillies | W | |||

| 1996 | Not played | Cleveland Indians | W | New York Yankees | L | |||

| 1997 | Not played | Seattle Mariners | W | Cleveland Indians | L | |||

| 2012 | Texas Rangers | W | New York Yankees | L | ||||

| 2014 | Bye | Detroit Tigers | W | Kansas City Royals | L | |||

| 2016 | Toronto Blue Jays | L | ||||||

| 2023 | Bye | Texas Rangers | L | |||||

Baseball Hall of Famers

| Baltimore Orioles Hall of Famers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ford C. Frick Award (broadcasters only)

| Baltimore Orioles Ford C. Frick Award recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Retired numbers

The Orioles will retire a number only when a player has been inducted into the Hall of Fame with Cal Ripken Jr. being the only exception.[N 1] However, the Orioles have placed moratoriums on other former Orioles' numbers following their deaths (see note below).[68] To date, the Orioles have retired the following numbers:

|

Note: Cal Ripken Sr.'s number 7, Elrod Hendricks' number 44, and Mike Flanagan's number 46 have not officially been retired, but a moratorium has been placed on them and they have not been issued by the team since their deaths.

†Jackie Robinson's number 42 is retired throughout Major League Baseball

Maryland State Athletic Hall of Fame

| Orioles in the Maryland State Athletic Hall of Fame | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name | Position | Tenure | Notes |

| 9, 16 | Brady Anderson | OF | 1988–2001 | Born in Silver Spring |

| 3, 10 | Harold Baines | DH/RF | 1993–1995 1997–1999 2000 | Elected on his performance with Chicago White Sox and the Orioles, born in Easton |

| 13, 29, 59 | Steve Barber | P | 1960–1967 | Born in Takoma Park |

| 22, 48 | Jack Fisher | P | 1959–1962 | Born in Frostburg |

| 29 | Ray Moore | P | 1955–1957 | Born in Meadows |

| 36 | Tom Phoebus | P | 1966–1970 | Attended Mount Saint Joseph College, born in Baltimore |

| 3, 7 | Billy Ripken | 2B | 1987–1992, 1996 | Born in Havre de Grace, raised in Aberdeen |

| 8 | Cal Ripken Jr. | SS/3B | 1981–2001 | Born in Havre de Grace, raised in Aberdeen |

| 5 | Brooks Robinson | 3B | 1955–1977 | |

Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame

The Orioles' official team hall of fame is located on display on Eutaw Street at Camden Yards.

Team captains

- 33 Eddie Murray, 1B/DH, 1986–1988

Roster

Minor league affiliates

The Baltimore Orioles farm system consists of seven minor league affiliates.[69]

Franchise records and award winners

Individual records – batting

- Highest batting average: .340, Melvin Mora (2004)

- Most at bats: 673, B. J. Surhoff (1999)

- Most plate appearances: 749, Brady Anderson (1992)

- Most games: 163, Brooks Robinson (1961, 1964) and Cal Ripken (1996)

- Most runs: 132, Roberto Alomar (1996)

- Most hits: 214, Miguel Tejada (2006)

- Most total bases: 370, Chris Davis (2013)

- Highest slugging %: .646, Jim Gentile (1961)

- Highest on-base %: .442, Bob Nieman (1956)

- Most singles: 158, Al Bumbry (1980)

- Most doubles: 56, Brian Roberts (2009)

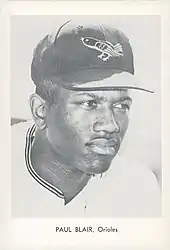

- Most triples: 12, Paul Blair (1967)

- Most home runs, RHB: 49, Frank Robinson (1966)

- Most home runs, LHB: 53, Chris Davis (2013)

- Most home runs, leadoff hitter: 35, Brady Anderson (1996)

- Most home runs, leading off game: 12, Brady Anderson (1996)

- Most consecutive games leading off with a home run: 4, Brady Anderson (April 18–21, 1996)

- Most extra base hits: 96, Chris Davis (2013)

- Most RBI, LHB: 142, Rafael Palmeiro (1996)

- Most RBI, RHB: 150, Miguel Tejada (2004)

- Most RBI, switch: 124, Eddie Murray (1985)

- Most RBI, month: 37, Albert Belle (June 2000)

- Most GWRBI: 25, Rafael Palmeiro (1998)

- Most consecutive games hit safely: 30, Eric Davis (1998)

- Most sac hits: 23, Mark Belanger (1975)

- Most sac flies: 17, Bobby Bonilla (1996)

- Most stolen bases: 57, Luis Aparicio (1964)

- Most walks: 118, Ken Singleton (1975)

- Most intentional walks: 25, Eddie Murray (1984)

- Most strikeouts: 219, Chris Davis (2016)

- Fewest strikeouts: 19, Rich Dauer (1980)

- Most hit by pitch: 24, Brady Anderson (1999)

- Most GIDP: 32, Cal Ripken (1985)

- Most pinch hits: 24, Dave Philley (1961)

- Most consecutive pinch hits: 6, Bob Johnson (1964)

- Most pinch hit RBI: 18, Dave Philley (1961)

Individual records – pitching

- Most games: 81, Jamie Walker (2007)

- Most games, rookie: 67, Jorge Julio (2002)

- Most games, started: 40, Dave McNally (1969–70), Mike Cuellar (1970), Jim Palmer (1976), and Mike Flanagan (1978)

- Most games started, rookie: 36, Bob Milacki (1989)

- Most complete games: 25, Jim Palmer (1975)

- Most games finished: 63, Jim Johnson (2012–13)

- Most wins: 25, Steve Stone (1980)

- Most wins, rookie: 19, Wally Bunker (1964)

- Most losses: 21, Don Larsen (1954)

- Best won-lost %: .808, Dave McNally (1971)

- Most bases on balls: 181, Bob Turley (1954)

- Most hit batsmen: 18, Daniel Cabrera (2008)

- Most strikeouts: 221, Érik Bédard (2007)

- Most innings pitched: 323, Jim Palmer (1975)

- Most innings pitched, rookie: 243, Bob Milacki (1989)

- Most shutouts: 10, Jim Palmer (1975)

- Most consecutive shutout innings: 36, Hal Brown (July 7 – August 8, 1961)

- Most home runs allowed: 35, 4 times; last: Jeremy Guthrie (2009)

- Fewest home runs allowed (by qualifier): 8, Milt Pappas (209 IP) (1959) and Billy Loes (155 IP) (1957)

- Lowest ERA (by qualifier): 1.95, Dave McNally (1968)

- Highest ERA (by qualifier): 5.90, Rodrigo Lopez (2006)

- Most saves: 51, Jim Johnson (2012)

- Most saves, rookie: 27, Gregg Olson (1989)

- Most wins, reliever: 14, Stu Miller (1965)

- Most relief points: 131, Randy Myers (1997)

- Most innings pitched by reliever: 140.1, Sammy Stewart (1983)

- Most consecutive wins: 15, Dave McNally (April 12 – August 3, 1969)

- Most consecutive losses: 10, Jay Tibbs (July 10 – October 1, 1988)

- Most consecutive losses, start of season: 8, Mike Boddicker (1988) and Jason Johnson (2000)

- Most wins vs. one club: 6, Wally Bunker vs. Kansas City (1964)

- Most losses vs. one club: 5 Don Larsen vs. White Sox (1954), Joe Coleman vs. Yankees (1954), and Jim Wilson vs. Cleveland (1955)

- Most wins by opponent: 6, Andy Pettitte, Yankees (2003) and Bud Daley, Kansas City (1959)

- Most losses by opponent: 5, Ned Garver, Kansas City (1957), Dick Stigman, Minnesota (1963), Stan Williams, Cleveland (1969), and Catfish Hunter, Yankees (1976)

Rivalries

The Orioles have a regional rivalry[70] with the nearby Washington Nationals nicknamed the Beltway Series or Battle of the Beltways. Baltimore currently leads the series with a 55–39 record over the Nationals.

Notes

- Ripken's number was retired on October 6, 2001, in a ceremony moments before his last professional game.

References

- "Orioles announce uniform changes for 2012". Orioles.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. November 15, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

The club's new home cap will feature the cartoon bird on a white front panel with a black back and orange bill and button.

- "Orioles Logos & Mascots". Orioles.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- Trezza, Joe (December 21, 2020). "How the oriole became a baseball bird". Orioles.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

To this day, the club has made minimal changes to the orange-and-black color scheme that makes the Baltimore Orioles – and Baltimore orioles – distinctive.

- Klingaman, Mike (September 26, 2019). "Why Not?; Remembering the 1989 Orioles' remarkable turnaround 30 years later". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- punkrawka (January 28, 2013). "The 2012 Orioles: the DVD". Camden Chat.

- Kamin, Blair. "Camden Yards paved a retro revolution — and influenced Wrigley Field's renovations". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Weigel, Brandon. "A More Complex Legacy: Oriole Park is known as "the ballpark that forever changed baseball", and its impact may well extend to local governing". Baltimore City Paper. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Meoli, Jon (December 31, 2018). "Orioles rated as worst team in all of sports in 2018". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- "Baltimore Orioloes Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Events of Thursday, April 25, 1901". Retrosheet.org. April 25, 1902. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- Bialik, Carl (July 28, 2008). "Baseball's Biggest Ninth-Inning Comebacks". The Wall Street Journal.

- St. Louis Browns: 1902–1953, Bleacher Report, Andrew Godfrey. "In 1953 Veeck would request to move the team to Baltimore but the move was approved on the condition Veeck would give up his interest in the team ..."

- Team First: History of Baseball Integration & Civil Rights, Lloyd H. Barrow, Page Publishing, 2018.

- "The Oriole Bird". Baltimore Orioles. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- Flynn, Tom (2008). Baseball in Baltimore. Maryland: Arcadia Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7385-5325-2.

- "A Fond Farewell To A Baseball Man Who Wasn't Afraid To Take Chances". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- Silver, Zachary (February 28, 2022). "Baltimore bid goodbye to Earl Weaver, then won a World Series". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- "THE ORIOLES' NEW OWNERS". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- "1994 Baltimore Orioles season summary". Baseball-Reference.Com. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- Shin, Annys (August 30, 2018). "When Cal Ripken Jr. broke Lou Gehrig's record for consecutive games played". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- "Poor Communication at Heart of Feud". The Washington Post. May 12, 1998.

- Ghiroli, Brittany (April 27, 2015). "Protests force postponement of O's-White Sox on Monday". The Baltimore Orioles. MLB. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- "Orioles announcement regarding schedule changes". @Baltimore Orioles (twitter). Baltimore Orioles. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- "Orioles, White Sox will play in empty Baltimore stadium Wednesday". News & Record. Associated Press. April 28, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- "MLB Baseball Box Score – Chicago vs. Baltimore – Apr 29, 2015". CBSSports.com. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- Brittany, Ghiroli (April 28, 2015). "White Sox-O's postponed; tomorrow closed to fans". The Baltimore Orioles. MLB.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- "Orioles Game Vs. White Sox Postponed Following Baltimore Riots". WJZ-TV. CBS Baltimore. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- Marbella, Jean; Barker, Jeff. "Lawsuit between Peter Angelos' sons lays bare secret struggle over Baltimore Orioles' future, possible sale of team". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- "Wife of Orioles owner Peter Angelos says she has 'full faith' in son John Angelos as head of the team". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- "Amid legal battle with brother, Orioles chairman and CEO John Angelos says team 'will never leave' Baltimore". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- "Major League Baseball has encouraged Cal Ripken Jr. to become part of ownership group if Orioles are sold, sources say". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- "Monday Bird Droppings: The Orioles wrapped up an outstanding April". camdenchat.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- Ghiroli, Brittany (August 7, 2023). "Ghiroli: Orioles' unforced error with announcer Kevin Brown dims team's shine at wrong time". The Athletic. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Gardner, Steve (August 8, 2023). "MLB announcers express outrage after reports of Orioles suspending TV voice Kevin Brown". USA Today. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- "Baltimore Orioles Attendance, Stadiums, and Park Factors". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- "Battle of the Uniforms: Orioles win title". ESPN.com. May 20, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- "O's drop bold new City Connect jerseys – with a surprise inside". MLB.com.

- The Sporting News, March 22, 1945, p. 16.

- Trezza, Joe. "O's, MASN announce '21 broadcast team". Major League Baseball. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Ruiz, Nathan (January 23, 2021). "'I'll treasure that forever': Gary Thorne not returning to Orioles broadcasts in 2021". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- Meoli, Jon. "Gary Thorne, Jim Palmer, others won't be at Camden Yards for broadcasts as Orioles limit in-person announce teams". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- Lucia, Joe (February 28, 2022). "Kevin Brown will be Orioles full-time TV broadcaster in 2022". Awful Announcing. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- "Orioles lose appeal in $100 million MASN dispute with Nationals, will challenge in New York's highest court". The Baltimore Sun.

- Zurawik, David. "After 64 years, no lineup of Orioles games will be on Baltimore broadcast TV in 2018". The Baltimore Sun.

- Trezza, Joe. "Why O's fans yell 'Oh!' during anthem". MLB.com. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- Lee, Edward. "'It was like a home game' vs. Panthers, said Ravens quarterback Joe Flacco". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- "Ravens hold on to win Super Bowl, 34–31". The Baltimore Sun. February 4, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- Steinberg, Dan (August 10, 2016). "Baltimore's National Anthem 'Oh!' gives Michael Phelps a gold-medal laugh". D.C. Sports Bog. The Washington Post.

- Gibbons, Mike (July 5, 2007). "Baltimore's Seventh-Inning Tradition Within a Tradition". pressboxonline.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- "John Denver At Camden Yards | 7th-inning stretch belonged to Denver Orioles: Time after time, 'Thank God I'm a Country Boy' got the stadium rocking. And when the man himself joined in, it was magic". The Baltimore Sun. October 14, 1997. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- Walt Woodward (1970). "Orioles Magic (Feel It Happen)". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "August 1997". baseballlibrary.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2003. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- "Ryan Wagner selected as new voice of Oriole Park | orioles.com: News". Baltimore.orioles.mlb.com. February 21, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012. and did so through the end of the 2020 season.

- "Baines, Harold". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Guerrero, Vladimir". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Herzog, Whitey". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Jackson, Reggie". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Murray, Eddie". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Mussina, Mike". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Palmer, Jim". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Sr. Raines, Tim". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Jr. Ripken, Cal". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Thome, Jim". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "Weaver, Earl". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- Carr, Samantha (December 6, 2010). "Emotional Election". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- "Paper of Record". Paperofrecord.hypernet.ca. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- "Orioles Insider: Guthrie wants to know whether he should keep No. 46 – Baltimore Orioles: Schedule, news, analysis and opinion on baseball at Camden Yards". The Baltimore Sun. August 25, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- "Baltimore Orioles Minor League Affiliates". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- "Orioles-Nats weekend series gives beltway something to be excited about". Retrieved April 7, 2013.

Bibliography

- Bready, James H. The Home Team. 4th ed. Baltimore: 1984.

- Eisenberg, John. From 33rd Street to Camden Yards. New York: Contemporary Books, 2001.

- Hawkins, John C. This Date in Baltimore Orioles & St. Louis Browns History. Briarcliff Manor, New York: Stein & Day, 1983.

- Miller, James Edward. The Baseball Business: Pursuing Pennants and Profits in Baltimore. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

- Patterson, Ted. The Baltimore Orioles. Dallas: Taylor Publishing Co., 1994.

External links

- Official website

- Waldman, Ed. "Sold! Angelos scored with '93 home run" Archived October 29, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, The Baltimore Sun, August 1, 2004

- "St. Louis Browns photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis.

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1966 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1970 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1983 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions St. Louis Browns 1944 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Baltimore Orioles 1966 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions 1969–1971 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions 1979 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions 1983 |

Succeeded by |