Emakimono

Illustrated handscrolls, emakimono (絵巻物, lit. 'illustrated scroll', also emaki-mono), or emaki (絵巻) is an illustrated horizontal narration system of painted handscrolls that dates back to Nara-period (710–794 CE) Japan. Initially copying their much older Chinese counterparts in style, during the succeeding Heian (794–1185) and Kamakura periods (1185–1333), Japanese emakimono developed their own distinct style. The term therefore refers only to Japanese painted narrative scrolls.

As in the Chinese and Korean scrolls, emakimono combine calligraphy and illustrations and are painted, drawn or stamped on long rolls of paper or silk sometimes measuring several metres. The reader unwinds each scroll little by little, revealing the story as seen fit. Emakimono are therefore a narrative genre similar to the book, developing romantic or epic stories, or illustrating religious texts and legends. Fully anchored in the yamato-e style, these Japanese works are above all an everyday art, centered on the human being and the sensations conveyed by the artist.

Although the very first 8th-century emakimono were copies of Chinese works, emakimono of Japanese taste appeared from the 10th century in the Heian imperial court, especially among aristocratic ladies with refined and reclusive lives, who devoted themselves to the arts, poetry, painting, calligraphy and literature. However, no emakimono remain from the Heian period, and the oldest masterpieces date back to the "golden age" of emakimono in the 12th and 13th centuries. During this period, the techniques of composition became highly accomplished, and the subjects were even more varied than before, dealing with history, religion, romances, and other famous tales. The patrons who sponsored the creation of these emakimono were above all the aristocrats and Buddhist temples. From the 14th century, the emakimono genre became more marginal, giving way to new movements born mainly from Zen Buddhism.

Emakimono paintings mostly belong to the yamato-e style, characterized by its subjects from Japanese life and landscapes, the staging of the human, and an emphasis on rich colours and a decorative appearance. The format of the emakimono, long scrolls of limited height, requires the solving of all kinds of composition problems: it is first necessary to make the transitions between the different scenes that accompany the story, to choose a point of view that reflects the narration, and to create a rhythm that best expresses the feelings and emotions of the moment. In general, there are thus two main categories of emakimono: those which alternate the calligraphy and the image, each new painting illustrating the preceding text, and those which present continuous paintings, not interrupted by the text, where various technical measures allow the fluid transitions between the scenes.

Today, emakimono offer a unique historical glimpse into the life and customs of Japanese people, of all social classes and all ages, during the early part of medieval times. Few of the scrolls have survived intact, and around 20 are protected as National Treasures of Japan.

Concept

| External media | |

|---|---|

| Images | |

| Video | |

The term emakimono or e-makimono, often abbreviated as emaki, is made up of the kanji e (絵, "painting"), maki (巻, "scroll" or "book") and mono (物, "thing").[1] The term refers to long scrolls of painted paper or silk, which range in length from under a metre to several metres long; some are reported as measuring up to 12 metres (40 ft) in length.[2] The scrolls tell a story or a succession of anecdotes (such as literary chronicles or Buddhist parables), combining pictorial and narrative elements, the combination of which characterises the dominant art movements in Japan between the 12th and 14th centuries.[2]

An emakimono is read, according to the traditional method, sitting on a mat with the scroll placed on a low table or on the floor. The reader then unwinds with one hand while rewinding it with the other hand, from right to left (according to the writing direction of Japanese). In this way, only part of the story can be seen – about 60 centimetres (24 in), though more can be unrolled – and the artist creates a succession of images to construct the story.[3]

Once the emakimono has been read, the reader must rewind the scroll again in its original reading direction. The emakimono is kept closed by a cord and stored alone or with other rolls in a box intended for this purpose, and which is sometimes decorated with elaborate patterns. An emakimono can consist of several successive scrolls as required of the story – the Hōnen Shōnin Eden was made up of 48 scrolls, although the standard number typically falls between one and three.[4]

An emakimono is made up of two elements: the sections of calligraphic text known as kotoba-gaki, and the sections of paintings referred to as e;[5] their size, arrangement and number vary greatly, depending on the period and the artist. In emakimono inspired by literature, the text occupies no less than two-thirds of the space, while other more popular works, such as the Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, favour the image, sometimes to the point of making the text disappear. The scrolls have a limited height (on average between 30 cm (12 in) and 39 cm (15 in)), compared with their length (on average 9 m (30 ft) to 12 m (39 ft)),[4] meaning that emakimono are therefore limited to being read alone, historically by the aristocracy and members of the high clergy.[6]

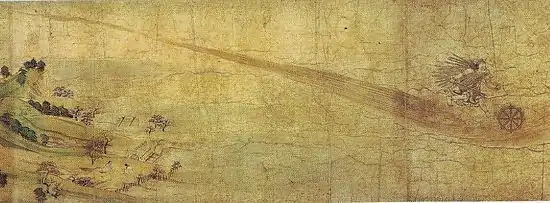

Example of a complete scroll of an emakimono, the Ippen Shōnin Eden (seventh scroll, 1299, Tokyo National Museum). Reading direction is from right to left. Traditionally, the reader never fully unwinds the roll, but unwinds it with one hand while rewinding it with the other, learning the story piecemeal.

Example of a complete scroll of an emakimono, the Ippen Shōnin Eden (seventh scroll, 1299, Tokyo National Museum). Reading direction is from right to left. Traditionally, the reader never fully unwinds the roll, but unwinds it with one hand while rewinding it with the other, learning the story piecemeal.

History

Origins

Handscrolls are believed to have been invented in India before the 4th century CE. They were used for religious texts and entered China by the 1st century. Handscrolls were introduced to Japan centuries later through the spread of Buddhism. The earliest extant Japanese handscroll was created in the 8th century and focuses on the life of the Buddha.[2]

The origins of Japanese handscrolls can be found in China and, to a lesser extent, in Korea, the main sources of Japanese artistic inspiration until modern times. Narrative art forms in China can be traced back to between the 3rd century CE under the Han dynasty and the 2nd century CE under the Zhou dynasty, the pottery of which was adorned with hunting scenes juxtaposed with movements.[7] Paper was invented in China in about the 1st century CE, simplifying the writing on scrolls of laws or sutra, sometimes decorated. The first narrative scrolls arrived later; various masters showed interest in this medium, including Gu Kaizhi (345–406), who experimented with new techniques. Genre painting and Chinese characters, dominant in the scrolls up to the 10th century CE, remain little known to this day, because they were overshadowed by the famous landscape scrolls of the Song dynasty.[7]

Relations with East Asia (mainly China and Korea) brought Chinese writing (kanji) to Japan by the 4th century, and Buddhism in the 6th century, together with interest in the apparently very effective bureaucracy of the mighty Chinese Empire. In the Nara period, the Japanese were inspired by the Tang dynasty:[8] administration, architecture, dress customs or ceremonies. The exchanges between China and Japan were also fruitful for the arts, mainly religious arts, and the artists of the Japanese archipelago were eager to copy and appropriate continental techniques. In that context, experts assume that the first Chinese painted scrolls arrived on the islands around the 6th century CE, and probably correspond to illustrated sutra. Thus, the oldest known Japanese narrative painted scroll (or emakimono) dates from the 7th century to the Nara period: the Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect, which traces the life of the Gautama Buddha, founder of the Buddhist religion, until his Illumination.[9] Still naive in style (Six Dynasties and early Tang dynasty) with the paintings arranged in friezes above the text, it is very likely a copy of an older Chinese model, several versions of which have been identified.[10][11] Although subsequent classical emakimono feature a very different style from that of this work, it foreshadows the golden age of the movement that came four centuries later, from the 12th century CE onwards.[8]

Arts and literature, birth of a national aesthetic

The Heian period appears today as a peak of Japanese civilization via the culture of the emperor's court, although intrigue and disinterest in things of the state resulted in the Genpei War.[12] This perception arises from the aesthetics and the codified and refined art of living that developed at the Heian court, as well as a certain restraint and melancholy born from the feeling of the impermanence of things (a state of mind referred to as mono no aware in Japanese).[13] Furthermore, the rupture of relations with China until the 9th century, due to disorders related to the collapse of the glorious Tang dynasty, promoted what Miyeko Murase has described as the "emergence of national taste" as a truly Japanese culture departed for the first time from Chinese influence since the early Kofun period.[14] This development was first observed in the literature of the Heian women: unlike the men, who studied Chinese writing from a young age, the women adopted a new syllabary, hiragana, which was simpler and more consistent with the phonetics of Japanese.[15] Heian period novels (monogatari) and diaries (nikki) recorded intimate details about life, love affairs and intrigues at court as they developed; the best known of these is the radical Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu, lady-in-waiting of the 10th century Imperial Court.[16][17]

The beginnings of the Japanese-inspired Heian period painting technique, retrospectively named yamato-e, can be found initially in some aspects of Buddhist painting of the new esoteric Tendai and Shingon sects, then more strongly in Pure Land Buddhism (Jodō); after a phase when Chinese techniques were copied, the art of the Japanese archipelago became progressively more delicate, lyrical, decorative with less powerful but more colorful compositions.[18] Nevertheless, it was especially in secular art that the nascent yamato-e was felt most strongly;[19] its origins went back to the sliding partitions and screens of the Heian Imperial Palace, covered with paintings on paper or silk, the themes of which were chosen from waka court poetry, annual rites, seasons or the famous lives and landscapes of the archipelago (meisho-e).[20]

This secular art then spread among the nobles, especially the ladies interested in the illustration of novels, and seems to have become prevalent early in the 10th century. As with religious painting, the themes of Japanese life, appreciated by the nobles, did not fit well with painting of Chinese sensibility, so much so that court artists developed to a certain extent a new national technique which appeared to be fashionable in the 11th century,[21] for example in the seasonal landscapes of the panel paintings in the Phoenix Hall (鳳凰堂, Hōō-dō) or Amida Hall at the Byōdō-in temple, a masterpiece of primitive yamato-e of the early 11th century.[22]

Experts believe that yamato-e illustrations of novels and painted narrative scrolls, or emakimono, developed in the vein of this secular art, linked to literature and poetry.[23] The painting technique lent itself fully to the artistic tastes of the court in the 11th century, inclined to an emotional, melancholic and refined representation of relations within the palace, and formed a pictorial vector very suited to the narrative.[19] Even though they are mentioned in the antique texts, no emakimono of the early Heian period (9th and 10th centuries) remains extant today;[24] the oldest emakimono illustrating a novel mentioned in period sources is that of the Yamato Monogatari, offered to the Empress between 872 and 907.[25]

However, the stylistic mastery of later works (from the 12th century) leads most experts to believe that the "classical" art of emakimono grew during this period from the 10th century, first appearing in illustrations in novels or diaries produced by the ladies of the court.[26] In addition, the initial themes remained close to waka poetry (seasons, Buddhism, nature and other themes).[27] Therefore, the slow maturation of the movement of emakimono was closely linked to the emergence of Japanese culture and literature, as well as to the interest of courtesans soon joined by professional painters from palace workshops (e-dokoro) or temples, who created a more "professional" and successful technique.[21] The art historians consider that the composition and painting techniques they see in the masterpieces of the late Heian period (second half of the 12th century) were already very mature.[28]

Fujiwara era: classical masterpieces

If almost all emakimono belong to the genre of yamato-e, several sub-genres stand out within this style, including in the Heian period onna-e ("women's painting") and otoko-e ("men's painting").[29] Several classic scrolls of each genre perfectly represent these pictorial movements.

First, the Genji Monogatari Emaki (designed between around 1120 and 1140), illustrating the famous eponymous novel, narrates the political and amorous intrigues of Prince Hikaru Genji;[30] the rich and opaque colors affixed over the entire surface of the paper (tsukuri-e method), the intimacy and melancholy of the composition and finally the illustration of the emotional peaks of the novel taking place only inside the Imperial Palace are characteristics of the onna-e subgenre of yamato-e, reserved for court narratives usually written by aristocratic ladies.[31] In that scroll, each painting illustrates a key episode of the novel and is followed by a calligraphic extract on paper richly decorated with gold and silver powder.[32]

The Genji Monogatari Emaki already presents the composition techniques specific to the art of emakimono: an oblique point of view, the movement of the eyes guided by long diagonals from the top right to the bottom left, and even the removal of the roofs to represent the interior of buildings (fukinuki yatai).[25] A second notable example of the onna-e paintings in the Heian period is the Nezame Monogatari Emaki, which appears to be very similar to the Genji Monogatari Emaki, but presents softer and more decorative paintings giving pride of place to the representation of nature subtly emphasising the feelings of the characters.[25][33]

In contrast with court paintings inspired by women's novels (onna-e) there are other scrolls inspired by themes such as the daily lives of the people, historical chronicles, and the biographies of famous monks; ultimately, a style of emakimono depicting matters outside the palace and called otoko-e ("men's painting").[34][29]

The Shigisan Engi Emaki (middle of the 12th century), with dynamic and free lines, light colors and a decidedly popular and humorous tone, perfectly illustrate this movement, not hesitating to depict the life of the Japanese people in its most insignificant details.[35][36] Here, the color is applied only in light touches that leave the paper bare, as the supple and free line dominates the composition, unlike the constructed paintings of the court.[37] In addition, the text occupies very limited space, the artist painting rather long scenes without fixed limits.[38]

Two other masterpieces emerged into the light of day during the second half of the 12th century.[39]

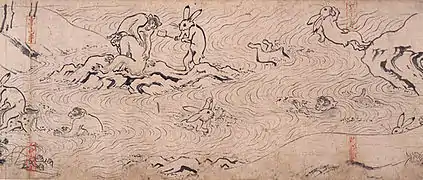

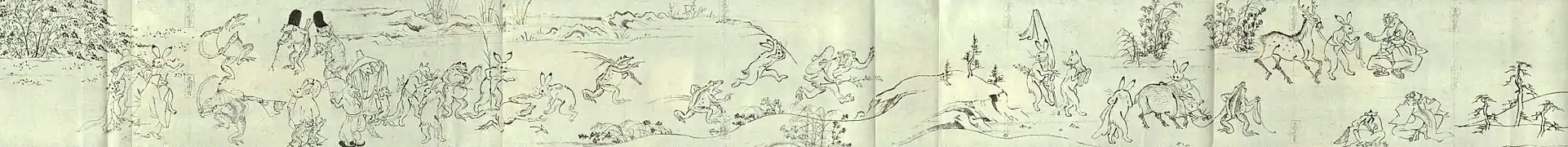

First, the Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga forms a monochrome sketch in ink gently caricaturing the customs of Buddhist monks, where the spontaneity of touch stands out.[40] Secondly, the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba tells of a political conspiracy in the year 866 by offering a surprising mixture of the two genres onna-e and otoko-e, with free lines and sometimes light, sometimes rich and opaque colors; this meeting of genres foreshadows the style that dominated a few decades later, during the Kamakura period.[41]

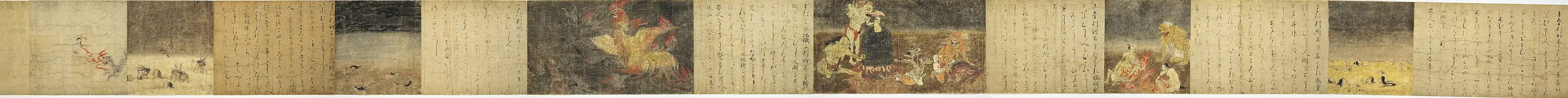

While the authority of the court rapidly declined, the end of the Heian period (in 1185) was marked by the advent of the provincial lords (in particular, the Taira and the Minamoto), who acquired great power at the top of the state.[42] Exploiting the unrest associated with the Genpei War, which provided fertile ground for religious proselytism, the six realms (or destinies) Buddhist paintings (rokudō-e) – such as the Hell Scroll or the two versions of the Gaki Zōshi, otoko-e paintings – aimed to frighten the faithful with horror scenes.[43][44]

Retracing the evolution of emakimono remains difficult, due to the few works that have survived. However, the obvious mastery of the classical scrolls of the end of the Heian period testifies to at least a century of maturation and pictorial research. These foundations permitted the emakimono artists of the ensuing Kamakura period to engage in sustained production in all of the themes.

Kamakura period: the golden age of emakimono

The era covering the end of the Heian period and much of the Kamakura period, or the 12th and 13th centuries, is commonly described by art historians as "the golden age" of the art of emakimono.[45][46] Under the impetus of the new warrior class in power, and the new Buddhist sects, production was indeed very sustained and the themes and techniques more varied than before.[47]

The emakimono style of the time was characterized by two aspects: the synthesis of the genres of yamato-e, and realism. Initially, the evolution marked previously by the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba (very late Heian era) was spreading very widely due to the importance given both to the freedom of brush strokes and the lightness of the tones (otoko-e), as well as bright colors rendered by thick pigments for certain elements of the scenes (onna-e).[48] However, the very refined appearance of the court paintings later gave way to more dynamic and popular works, at least in relation to the theme, in the manner of the Shigisan Engi Emaki.[49] For example, the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki recounts the life and death of Sugawara no Michizane, Minister in the 9th century and tragic figure in Japanese history, revered in the manner of a god (kami). The rich colours, the tense contours, the search for movement and the very realistic details of the faces well illustrate this mixture of styles,[50] especially as the paintings drew their inspiration from both Buddhism and Shinto.[51]

The realistic trends that were in vogue in Kamakura art, perfectly embodied by sculpture,[52] were exposed in the majority of the Kamakura emakimono; indeed, the bakufu shogunate system held power over Japan, and the refined and codified art of the court gave way to more fluidity and dynamism.[53] The greater simplicity advocated in the arts led to a more realistic and human representation (anger, pain or size).[54] If the activity related to religion was prolific, then so too were the orders of the bushi (noble warriors). Several emakimono of historical or military chronicles are among the most famous, notably the Hōgen Monogatari Emaki (no longer extant) and the Heiji Monogatari Emaki;[55] of the latter, the scroll kept at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston remains highly regarded for its mastery of composition (which reaches a crescendo at the dramatic climax of the scroll, i.e. the burning of the palace and the bloody battle between foot soldiers), and for its contribution to present day understanding of Japanese medieval weapons and armour.[56] Akiyama Terukazu describes it as "a masterpiece on the subject of the world's military."[55] In the same spirit, a noble warrior had the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba designed to recount his military exploits during the Mongol invasions of Japan.[57] Kamakura art particularly flourished in relation to realistic portraiture (nise-e); if the characters in the emakimono therefore evolved towards greater pictorial realism, some, such as the Sanjūrokkasen emaki, or the Zuijin Teiki Emaki attributed to Fujiwara no Nobuzane, directly present portrait galleries according to the iconographic techniques of the time.[58][59]

A similar change was felt in religion as the esoteric Buddhist sects of the Heian era (Tendai and Shingon) gave way to Pure Land Buddhism (Jōdo), which primarily addressed the people by preaching simple practices of devotion to the Amida Buddha. These very active sects used emakimono intensively during the 13th and 14th centuries to illustrate and disseminate their doctrines.[60]

.jpg.webp)

Several religious practices influenced the Kamakura emakimono: notably, public sermons and picture explaining sessions (絵解, e-toki) led the artists to use scrolls of larger size than usual, and to represent the protagonists of the story in a somewhat disproportionate way compared with emakimono of the standard sizes, to enable those protagonists to be seen from a distance, in a typically Japanese non-realistic perspective (such as the Ippen Shōnin Eden). The religious emakimono of the Kamakura period focus on the foundation of the temples, or the lives of famous monks.[46] During that period, many of the religious institutions commissioned the workshops of painters (often monk-painters) to create emakimono recounting their foundation, or the biography of the founding monk. Among the best-known works on such themes are the illustrated biographies of Ippen, Hōnen, Shinran and Xuanzang, as well as the Kegon Engi Emaki and the Taima Mandara Engi Emaki.[61][62]

The Ippen biography, painted by a monk, remains remarkable for its influences, so far rare, from the Song dynasty (via the wash technique) and the Tang dynasty (the shan shui style), as well as by its very precise representations of forts in many Japanese landscapes.[63] As for the Saigyō Monogatari Emaki, it addresses the declining aristocracy in idealising the figure of the monk aesthete Saigyō by the beauty of its landscapes and its calligraphic poetry.[64]

Towards the middle of the Kamakura period, there was a revival of interest in the Heian court, which already appeared to be a peak of Japanese civilization, and its refined culture.[65] Thus the Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki, which traces the life and intrigues of Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji (10th century), largely reflects the painting techniques of the time, notably the tsukuri-e, but in a more decorative and extroverted style.[66] Other works followed that trend, such as Ise Monogatari Emaki, the Makura no Sōshi Emaki or the Sumiyoshi Monogatari Emaki.[67]

Muromachi period: decline and otogi-zōshi

By the end of the Kamakura period, the art of emakimono was already losing its importance. Experts note that, on the one hand, emakimono had become less inspired, marked by an extreme aesthetic mannerism (such as the exaggerated use of gold and silver powder) with a composition more technical than creative; the tendency to multiply the scenes in a fixed style can be seen in the Hōnen Shōnin Eden (the longest known emakimono, with 48 scrolls, completed in 1307), the Kasuga Gongen Genki E (1309) and the Dōjō-ji Engi Emaki (16th century).[68][69] On the other hand, the innovative and more spiritual influences of Chinese Song art, deeply rooted in spirituality and Zen Buddhism, initiated the dominant artistic movement of wash (ink or monochromatic painting in water, sumi-e or suiboku-ga in Japanese) in the ensuing Muromachi period, guided by such famous artists as Tenshō Shūbun or Sesshū Tōyō.[70]

A professional current was nevertheless maintained by the Tosa school: the only one still to claim the yamato-e, it produced many emakimono to the order of the court or the temples (this school of painters led the imperial edokoro until the 18th century). Tosa Mitsunobu notably produced several works on the foundation of temples: the Kiyomizu-dera Engi Emaki (1517), a scroll of the Ishiyama-dera Engi Emaki (1497), the Seikō-ji Engi emaki (1487) or a version of the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki (1503); he paid great attention to details and colours, despite a common composition.[71] In a more general way, the illustration of novels in the classic yamato-e style (such as the many versions of the Genji Monogatari Emaki or The Tales of Ise Emaki) persisted during late medieval times.[71]

_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg.webp)

If emakimono therefore ceased to be the dominant artistic media in Japan since the end of the Kamakura period, it is in the illustration movement of Otogi-zōshi (otogi meaning "to tell stories") that emakimono developed a new popular vigour in the 15th and 16th centuries (the Muromachi period); the term nara-ehon (literally, "the book of illustrations of Nara") sometimes designated them in a controversial way (because they were anachronistic and combined books with scrolls), or more precisely as otogi-zōshi emaki or nara-emaki.[72] These are small, symbolic and funny tales, intended to pass the time focusing on mythology, folklore, legends, religious beliefs or even contemporary society.[72] This particular form of emakimono dates back to Heian times, but it was under Muromachi that it gained real popularity.[73]

The relative popularity of otogi-zōshi seems to have stemmed from a burgeoning lack of enthusiasm for hectic or religious stories; the people had become more responsive to themes of dreams, laughter and the supernatural (a number of otogi-zōshi emaki depict all sorts of yōkai and folk creatures), as well as social caricatures and popular novels. Among the preserved examples are genre paintings such as Buncho no sasshi and Sazare-ichi,[74] or supernatural Buddhist tales such as the Tsuchigumo Sōshi or the Hyakki Yagyō Emaki.[lower-alpha 1] From the point of view of art historians, the creativity of classical scrolls is felt even less in otogi-zōshi, because even though the composition is similar, the lack of harmony of colors and the overloaded appearance are detrimental; it seems that the production is often the work of amateurs.[75] However, a field of study of nara-ehon and the nara-e pictorial style exists on the fringes and stands out from the framework of emakimono.[72]

Various other artists, notably Tawaraya Sōtatsu and Yosa Buson, were still interested in the narrative scroll until around the 17th century.[76] The Kanō school used narrative scrolls in the same way; Kanō Tan'yū realised several scrolls on the Tokugawa battles, particularly that of Sekigahara in his Tōshō Daigongen Engi, where he was inspired in places by the Heiji Monogatari Emaki (13th century).[77]

Features and production

Themes and genres

In essence, an emakimono is a narrative system (like a book) that requires the construction of a story, so the composition must be based on the transitions from scene to scene until the final denouement.

Emakimono were initially strongly influenced by China, as were the Japanese arts of the time; the Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect incorporates many of the naive, simple styles of the Tang dynasty, although dissonances can be discerned, especially in relation to colours.[78] From the Heian period onwards, emakimono came to be dissociated from China, mainly in their themes. Chinese scrolls were intended mainly to illustrate the transcendent principles of Buddhism and the serenity of the landscapes, suggesting the grandeur and the spirituality. The Japanese, on the other hand, had refocused their scrolls on everyday life and man, conveying drama, humour and feelings. Thus, emakimono began to be inspired by literature, poetry, nature and especially everyday life; in short, they formed an intimate art, sometimes in opposition to the search for Chinese spiritual greatness.

The first Japanese themes in the Heian period were very closely linked to waka literature and poetry: paintings of the seasons, the annual calendar of ceremonies, the countryside and finally the famous landscapes of the Japanese archipelago (meisho-e).[20] Subsequently, the Kamakura warriors and the new Pure Land Buddhist sects diversified the subjects even more widely. Despite the wide range of emakimono themes, specialists like to categorise them, both in substance and in form. An effective method of differentiating emakimono comes back to the study of the subjects by referring to the canons of the time. The categorisation proposed by Okudaira and Fukui thus distinguishes between secular and religious paintings:[79]

Secular paintings

- Court novels and diaries (monogatari, nikki) dealing with romantic tales, life at court or historical chronicles;

- Popular legends (setsuwa monogatari);

- Military accounts (kassen);

- Scrolls on waka poets;

- Reports on the rites and ceremonies celebrated in a very codified and rigid way throughout the year;

- Realistic paintings and portraits (nise-e);

- Otogi-zōshi, traditional or fantastic tales popular in the 14th century.

Religious paintings

- Illustrations of sutras or religious doctrines (kyu-ten);

- Illustrated biography of a prominent Buddhist monk or priest (shōnin, kōsōden-e or eden);

- Paintings of the antecedents of a temple (engi);

- The Zōshi, a collection of Buddhist anecdotes.

A third category covers more heterogeneous works, mixing religion and narration or religion and popular humour.

The artists and their audience

| External images | |

|---|---|

The authors of emakimono are most often unknown nowadays and it remains risky to speculate as to the names of the "masters" of emakimono. Moreover, a scroll can be the fruit of collaboration by several artists; some techniques such as tsukuri-e even naturally incline to such collaboration. Art historians are more interested in determining the social and artistic environment of painters: amateurs or professionals, at court or in temples, aristocrats or of modest birth.[80]

In the first place, amateur painters, perhaps the initiators of the classical emakimono, are to be found at the emperor's court in Heian, among the aristocrats versed in the various arts. Period sources mention in particular painting competitions (e-awase) where the nobles competed around a common theme from a poem, as described by Murasaki Shikibu in The Tale of Genji. Their work seems to focus more on the illustration of novels (monogatari) and diaries (nikki), rather feminine literature of the court. Monks were also able to produce paintings without any patronage.

Secondly, in medieval Japan there were professional painters' workshops (絵 所, literally 'painting office'); during the Kamakura period, professional production dominated greatly, and several categories of workshops were distinguished: those officially attached to the palace (kyūtei edokoro), those attached to the great temples and shrines (jiin edokoro), or finally those hosted by a few senior figures.[81][82] The study of certain colophons and period texts makes it possible to associate many emakimono with these professional workshops, and even sometimes to understand how they function.

When produced by the temple workshops, emakimono were intended mainly as proselytism, or to disseminate a doctrine, or even as an act of faith, because copying illustrated sutras must allow communion with the deities (a theory even accredits the idea that the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki would have aimed to pacify evil spirits).[51] Proselytising, favoured by the emergence of the Pure Land Buddhist sects during the Kamakura era, changed the methods of emakimono production, because works of proselytism were intended to be copied and disseminated widely in many associated temples, explaining the large number of more or less similar copies on the lives of great monks and the founding of the important temples.[83]

Various historians emphasise the use of emakimono in sessions of picture explaining (絵 解, e-toki), during which a learned monk detailed the contents of the scrolls to a popular audience. Specialists thus explicate the unusually large dimensions of the different versions of the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki or the Ippen Shōnin Eden. As for the workshops of the court, they satisfied the orders of the palace, whether for the illustration of novels or historical chronicles, such as the Heiji Monogatari Emaki. A form of exploitation of the story could also motivate the sponsor: for example, Heiji Monogatari Emaki were produced for the Minamoto clan (winner of the Genpei War), and the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba was created to extol the deeds of a samurai in search of recognition from the shōgun.[44] These works were, it seems, intended to be read by nobles. Nevertheless, Seckel and Hasé assert that the separation between the secular and the religious remains unclear and undoubtedly does not correspond to an explicit practice: thus, the aristocrats regularly ordered emakimono to offer them to a temple, and the religious scrolls do not refrain from representing popular things. So, for example, the Hōnen Shōnin Eden presents a rich overview of medieval civilization.[81]

Colophons and comparative studies sometimes allow for the deduction of the name of the artist of an emakimono: for example, the monk En'i signed the Ippen Shōnin Eden, historians designate Tokiwa Mitsunaga as the author of the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba and the Nenjū Gyōji Emaki, or Enichibō Jōnin for part of the Kegon Engi Emaki. Nevertheless, the life of these artists remains poorly known, at most they seem to be of noble extraction.[80] Such a background is particularly implied by the always very precise depictions in emakimono of the imperial palace (interior architecture, clothing and rituals) or official bodies (notably the imperial police (検非違使, kebiishi)). The Shigisan Engi Emaki illustrates that point well, as the precision of both religious and aristocratic motifs suggests that the painter is close to those two worlds.[25]

Perhaps a more famous artist is Fujiwara no Nobuzane, aristocrat of the Fujiwara clan and author of the Zuijin Teiki Emaki, as well as various suites of realistic portraits ("likeness pictures" (似絵, nise-e), a school he founded in honour of his father Fujiwara no Takanobu). Among the temple workshops, it is known that the Kōzan-ji workshop was particularly prolific, under the leadership of the monk Myōe, a great scholar who brought in many works from Song dynasty China. Thus, the Jōnin brushstrokes on the Kegon Engi Emaki or the portrait of Myōe reveal the first Song influences in Japanese painting. However, the crucial lack of information and documents on these rare known artists leads Japanese art historians rather to identify styles, workshops, and schools of production.[80]

From the 14th century, the Imperial Court Painting Bureau (宮廷絵所, Kyūtei edokoro), and even for a time the edokoro of the shōgun, were headed by the Tosa school, which, as mentioned above, continued Yamato-e painting and the manufacture of emakimono despite the decline of the genre. The Tosa school artists are much better known; Tosa Mitsunobu, for example, produced a large number of works commissioned by temples (including the Kiyomizu-dera Engi Emaki) or nobles (including the Gonssamen kassen emaki). The competing Kanō school also offered a such few pieces, on command: art historians have shown strong similarities between the Heiji Monogatari Emaki (12th century) and the Tōshō Daigongen Engi (17th century) by Kanō Tan'yū of the Kanō school, probably to suggest a link between the Minamoto and Tokugawa clans, members of which were, respectively, the first and last shoguns who ruled all of Japan.[84]

Materials and manufacture

The preferred support medium for emakimono is paper, and to a lesser extent silk; both originate from China, although Japanese paper (washi) is generally of a more solid texture and less delicate than Chinese paper, as the fibres are longer). The paper is traditionally made with the help of women of the Japanese archipelago.[85]

The most famous colors are taken from mineral pigments: for example azurite for blue, vermilion for red, realgar for yellow, malachite for green, amongst others. These thick pigments, named iwa-enogu in Japanese, are not soluble in water and require a thick binder, generally an animal glue;[86] the amount of glue required depends on how finely the pigments have been ground.[87]

As emakimono are intended to be rolled up, the colours must be applied to them in a thin, flat layer in order to avoid any cracking in the medium term, which limits the use of patterns (reliefs) predominant in Western painting.[87] As for the ink, also invented in China around the 1st century CE, it results from a simple mixture of binder and wood smoke, the dosage of which depends on the manufacturer. Essential for calligraphy, it is also important in Asian pictorial arts where the line often takes precedence; Japanese artists apply it with a brush, varying the thickness of the line and the dilution of the ink to produce a colour from a dark black to a pale gray strongly absorbed by the paper.[88]

Scrolls of paper or tissue remain relatively fragile, in particular after the application of paint. Emakimono are therefore lined with one or more layers of strong paper, in a very similar way to kakemono (Japanese hanging scrolls): the painted paper or silk is stretched, glued onto the lining, and then dried and brushed, normally by a specialized craftsman, known as a kyōshi (literally, 'master in sutra').[89] The long format of emakimono poses specific problems: generally, sheets of painted paper or silk 2–3 metres (6 ft 7 in – 9 ft 10 in) long are lined separately, then assembled using strips of long-fibre Japanese paper, known for its strength.[90] The lining process simply requires the application of an animal glue which, as it dries, also allows the painted paper or silk to be properly stretched. Assembly of the emakimono is finalised by the selection of the wooden rod (軸, jiku), which is quite thin, and the connection of the cover (表紙, hyōshi), which protects the work once it is rolled up with a cord (紐, himo); for the most precious pieces painted with gold and silver powder, a further protective blanket (見返し, mikaeshi, literally, 'inside cover') is often made of silk and decorated on the inside.[90][91]

Artistic characteristics

General

The currents and techniques of emakimono art are intimately linked and most often part of the yamato-e movement, readily opposed at the beginning to Chinese-style paintings, known as kara-e. Yamato-e, a colorful and decorative everyday art, strongly typifies the output of the time.[76] Initially, yamato-e mainly designated works with Japanese themes, notably court life, ceremonies or archipelago landscapes, in opposition to the hitherto dominant Chinese scholarly themes, especially during the Nara period.[92] The documents of the 9th century mention, for example, the paintings on sliding walls and screens of the then Imperial Palace, which illustrate waka poems.[20] Subsequently, the term yamato-e referred more generally to all of the Japanese style paintings created in the 9th century that expressed the sensitivity and character of the people of the archipelago, including those extending beyond the earlier themes.[92] Miyeko Murase thus speaks of "the emergence of national taste".[56]

Different currents of paintings are part of the yamato-e according to the times (about the 10th and 14th centuries), and are found in emakimono. The style, composition and technique vary greatly, but it is possible to identify major principles. Thus, in relation to style, the Heian period produced a contrast between refined court painting and dynamic painting of subjects outside the court, while the Kamakura period saw a synthesis of the two approaches and the contribution of new realistic influences of the Chinese wash paintings of the Song dynasty. In relation to composition, the artists could alternate calligraphy and painting so as to illustrate only the most striking moments of the story, or else create long painted sections where several scenes blended together and flowed smoothly. Finally, in relation to technique, the classification of emakimono, although complex, allows for two approaches to be identified: paintings favoring colour, and those favoring line for the purpose of dynamism.

The particular format of the emakimono, long strips of paintings without fixed limits, requires solving a number of compositional problems in order to maintain the ease and clarity of the narrative, and which have given rise to a coherent art form over several centuries. In summary, according to E. Saint-Marc: "We had to build a vocabulary, a syntax, solve a whole series of technical problems, invent a discipline that is both literary and plastic, an aesthetic mode which finds its conventions [...] in turn invented and modelled, frozen by use, then remodelled, to make it an instrument of refined expression."[93]

Overview of the Heian period yamato-e styles

Specialists like to distinguish between two currents in the yamato-e, and thus in the emakimono, of the Heian period, namely the onna-e ("painting of woman", onna meaning "woman"), and otoko-e ("painting of man", otoko meaning "man"). In the Heian period, these two currents of yamato-e also echoed the mysteries and the seclusion of the Imperial Court: the onna-e style thus told what happened inside the court, and the otoko-e style spoke of happenings in the populace outside.[94]

Court style: onna-e

Onna-e fully transcribed the lyrical and refined aesthetic of the court, which was characterized by a certain restraint, introspection and the expression of feelings, bringing together above all works inspired by "romantic" literature such as the Genji Monogatari Emaki.[95] The dominant impression of this genre is expressed in Japanese by the term mono no aware, a kind of fleeting melancholy born from the feeling of the impermanence of things. These works mainly adopted the so-called tsukuri-e (constructed painting) technique, with rich and opaque colours. In emakimono of the 13th century, in which the onna-e style was brought up-to-date, the same technique was used but in a sometimes less complete manner, the colours more directly expressing feelings and the artists using a more decorative aesthetic, such as with the very important use of gold dust in the Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki.[96]

A characteristic element of the onna-e resides in the drawing of the faces, very impersonal, that specialists often compare to Noh masks. Indeed, according to the hikime kagibana technique, two or three lines were enough to represent the eyes and the nose in a stylized way;[97] E. Grilli notes the melancholy of this approach.[41] The desired effect is still uncertain, but probably reflects the great restraint of feelings and personalities in the palace, or even allows readers to identify more easily with the characters.[98] In some monogatari of the Heian period, the artists rather expressed the feelings or the passions in the positions as well as in the pleats and folds of the clothes, in harmony with the mood of the moment.[50]

- Onna-e paintings

![Tsukuri-e [fr] painting, with vivid tones typical of primary yamato-e, Genji Monogatari Emaki, 12th century](../I/Genji_emaki_azumaya.jpg.webp) Tsukuri-e painting, with vivid tones typical of primary yamato-e, Genji Monogatari Emaki, 12th century

Tsukuri-e painting, with vivid tones typical of primary yamato-e, Genji Monogatari Emaki, 12th century_4.jpg.webp) Tsukiri-e painting in lighter tones, Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki, 13th century

Tsukiri-e painting in lighter tones, Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki, 13th century![Tsukiri-e painting, Ise Monogatari Emaki [fr], 14th century](../I/Ise_monogatari_emaki_-_Kubo_2.jpeg.webp) Tsukiri-e painting, Ise Monogatari Emaki, 14th century

Tsukiri-e painting, Ise Monogatari Emaki, 14th century Court scene illustrating hikime kagibana, a technique of inexpressive and impersonal representation of faces, Genji Monogatari Emaki, 12th century

Court scene illustrating hikime kagibana, a technique of inexpressive and impersonal representation of faces, Genji Monogatari Emaki, 12th century

Popular style: otoko-e

The current of the otoko-e style was freer and more lively than onna-e, representing battles, historical chronicles, epics and religious legends by favouring long illustrations over calligraphy, as in the Shigisan Engi Emaki or the Heiji Monogatari Emaki.[34] The style was based on soft lines drawn freely by the artist in ink, unlike tsukuri-e constructed paintings, to favour the impression of movement.[99] The colours generally appeared more muted and left the paper bare in places.[36]

If the term onna-e is well attested in the texts of the time, and seems to come from the illustrations of novels by the ladies of the court from the 10th century, the origins of the otoko-e are more obscure: they arise a priori from the interest of the nobles in Japanese provincial life from the 11th century, as well as from local folk legends; moreover, several very detailed scenes from the Shigisan Engi Emaki clearly show that its author can only have been a palace regular, aristocrat or monk.[100] In any case, there are still several collections of these folk tales of the time, such as the Konjaku Monogatarishū.[100]

Unlike the court paintings, the more spontaneous scrolls such as the Shigisan Engi Emaki or the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba display much more realism in the drawing of the characters, and depict, amongst other themes, humour and burlesque, with people's feelings (such as anger, joy and fear) expressed more spontaneously and directly.[25]

- Otoko-e paintings

Popular scene in which the lines take precedence over very light colors, Shigisan Engi Emaki, 12th century

Popular scene in which the lines take precedence over very light colors, Shigisan Engi Emaki, 12th century Another painting of a popular subject favouring the lines, Kokawa-dera Engi Emaki, 12th century

Another painting of a popular subject favouring the lines, Kokawa-dera Engi Emaki, 12th century Expressive painting of a communal crowd, Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, late 12th century

Expressive painting of a communal crowd, Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, late 12th century![Humorous scene depicting a doctor's mistake, Yamai no Sōshi [fr], 12th century](../I/Yamai_no_Soshi_-_Eye_Disease_(part_1).jpeg.webp) Humorous scene depicting a doctor's mistake, Yamai no Sōshi, 12th century

Humorous scene depicting a doctor's mistake, Yamai no Sōshi, 12th century Battle scene depicting one of the Mongol invasions of Japan, Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba, 13th century

Battle scene depicting one of the Mongol invasions of Japan, Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba, 13th century

Kamakura period realist painting

During the Kamakura period, the two currents of yamato-e (onna-e and otoko-e) mingled and gave birth to works that are both dynamic and vividly coloured, in the manner of the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki. Furthermore, the majority of emakimono also transcribed the realistic tendencies of the time, according to the tastes of the warriors in power. The Heiji Monogatari Emaki thus shows in great detail the weapons, armour and uniforms of the soldiers, and the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba individually portrays the more than two hundred panicked figures who appear on the section depicting the fire at the door.

Realistic painting is best displayed in the portraits known as nise-e, a movement initiated by Fujiwara no Takanobu and his son Fujiwara no Nobuzane. These two artists and their descendants produced a number of emakimono of a particular genre: they were suites of portraits of famous people made in a rather similar style, with almost geometric simplicity of clothing, and extreme realism of the face.[101] The essence of the nise-e was really to capture the intimate personality of the subject with great economy.[102]

Among the most famous nise-e scrolls are the Tennō Sekkan Daijin Eizukan, composed of 131 portraits of emperors, governors, ministers and senior courtiers (by Fujiwara no Tamenobu and Fujiwara no Gōshin, 14th century), and the Zuijin Teiki Emaki by Nobuzane, whose ink painting (hakubyō) enhanced with very discreet colour illustrates perfectly the nise-e lines.[59] Additionally, there is the Sanjūrokkasen Emaki, a work of a more idealized than realistic style, which forms a portrait gallery of the Thirty-Six Immortals of Poetry.[103] More generally, humans are one of the elementary subjects of emakimono, and many works of the Kamakura period incorporate nise-e techniques, such as the Heiji Monogatari Emaki or the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba.[54]

- Realist paintings

Colours and dynamism, Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, 13th century

Colours and dynamism, Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, 13th century

Detail of painting of very realistic warriors in faces, weapons and armor, Heiji Monogatari Emaki, 13th century

Detail of painting of very realistic warriors in faces, weapons and armor, Heiji Monogatari Emaki, 13th century

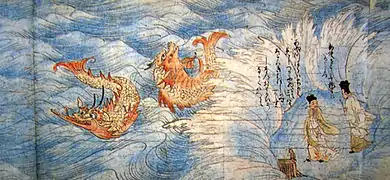

Chinese landscape and Song dynasty wash paintings

The yamato-e style therefore characterised almost all emakimono, and Chinese painting no longer provided the themes and techniques. However, influences were still noticeable in certain works of the Kamakura period, in particular the art, so famous today, of the Song dynasty wash paintings, which was fully demonstrated in the grandiose and deep landscapes sketched in ink, by Ienaga. Borrowings also remained visible in religious scrolls such as the Kegon Engi Emaki or the Ippen Shōnin Eden.[104] This last work presents many landscapes typical of Japan according to a perspective and a rigorous realism, with a great economy of colors; various Song pictorial techniques are used to suggest depth, such as birds' flights disappearing on the horizon or the background gradually fading.[105]

- Chinese-inspired paintings

Sinistically composed landscape of the Itsukushima Shrine in Miyajima and the famous floating torii, Ippen Shōnin Eden, 1299

Sinistically composed landscape of the Itsukushima Shrine in Miyajima and the famous floating torii, Ippen Shōnin Eden, 1299![Steep mountain landscape and hermitage, Kiyomizu-dera Engi Emaki [fr], 1517](../I/Kiyomizudera_engi_emaki_-_Scroll1_Pic3.jpg.webp) Steep mountain landscape and hermitage, Kiyomizu-dera Engi Emaki, 1517

Steep mountain landscape and hermitage, Kiyomizu-dera Engi Emaki, 1517 Zenmyō, a young Chinese woman, confesses her love to the monk Gishō during his stay in China, Kegon Engi Emaki, 13th century

Zenmyō, a young Chinese woman, confesses her love to the monk Gishō during his stay in China, Kegon Engi Emaki, 13th century

Tsukuri-e technique

The classic emakimono painting technique is called tsukuri-e (作り絵, lit. 'constructed painting'), used especially in most of the works of the onna-e style. A sketch of the outlines was first made in ink before applying the colours flat over the entire surface of the paper using vivid and opaque pigments. The outlines, partly masked by the paint, were finally revived in ink and the small details (such as the hair of the ladies) were enhanced.[106] However, the first sketch was often modified, in particular when the mineral pigments were insoluble in water and therefore required the use of thick glue.[88] Colour appears to be a very important element in Japanese painting, much more so than in China, because it gives meaning to the feelings expressed; in the Genji Monogatari Emaki, the dominant tone of each scene illustrating a key moment of the original novel reveals the deep feelings of the characters.[107]

During the Kamakura period, the different stages of tsukuri-e were still widely observed, despite variations (lighter colours, lines more similar to Song dynasty wash paintings, etc.).[108]

- Tsukuri-e technique (see also Court style: onna-e above)

Wailing women at Tomo no Yoshio house, Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, 12th century

Wailing women at Tomo no Yoshio house, Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, 12th century_6.jpg.webp) Drunk and disorderly court nobles interacting with court ladies, Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki, 13th century

Drunk and disorderly court nobles interacting with court ladies, Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki, 13th century Kubo version (using Tsukuri-e technique), Ise Monogatari Emaki, 14th century

Kubo version (using Tsukuri-e technique), Ise Monogatari Emaki, 14th century

Ink line and monochrome painting

Even though coloured emakimono often occupy a preponderant place, one finds in contrast monochrome paintings in India ink (hakubyō or shira-e), according to two approaches. First, ink lines can be extremely free, with the artist laying on paper unconstrained soft gestures that are especially dynamic, as it is mainly the sense of movement that emerges in these works.[41] The painter also plays on the thickness of the brush to accentuate the dynamism, as well as on the dilution of the ink to exploit a wider palette of grey.[88] Among such scrolls, the Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, formerly probably wrongly attributed to Toba Sōjō, remains the best known; Grilli describes the trait as a "continual outpouring".[76]

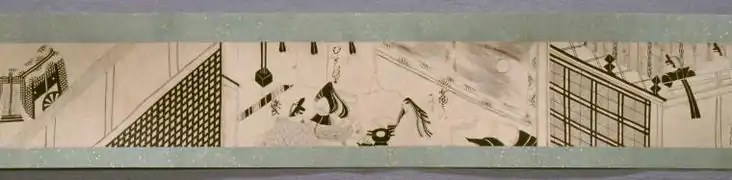

The second approach to monochrome paintings is more constructed, with fine, regular strokes sketching a complete and coherent scene, very similar to the first sketch in the tsukuri-e works before the application of the colours; according to some art historians, it is also possible that these emakimono are simply unfinished.[41] The Makura no Sōshi Emaki fits perfectly with this approach, accepting only a few fine touches of red, as do the Takafusa-kyō Tsuyakotoba Emaki and the Toyo no Akari Ezōshi.[67] Several somewhat amateurish hakubyō illustrations of classic novels remain from late medieval times and the decline of the emakimono.[71]

By contrast with Western painting, lines and contours in ink play an essential role in emakimono, monochrome or not.[76][37] Sometimes, however, contours are not drawn as usual: thus, in the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, the absence of contours is used by the artist to evoke the Shinto spirit in Japanese landscapes. Originally from China, this pictorial technique is now called mokkotsu ('boneless painting').[109]

- Ink line and monochrome painting (see also Popular style: otoko-e above)

Free ink painting, Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, 12th century

Free ink painting, Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, 12th century![Free ink painting, Shōgun-zuka Emaki [fr], 13th century](../I/Sh%C5%8Dgun-zuka_emaki%252C_detail_A.jpg.webp) Free ink painting, Shōgun-zuka Emaki, 13th century

Free ink painting, Shōgun-zuka Emaki, 13th century![Very constructed ink painting, similar to tsukuri-e without colour; the line is fine and uniform. Makura no Sōshi Emaki [fr], 13th century](../I/Pillow_Book_Illustrated2.JPG.webp) Very constructed ink painting, similar to tsukuri-e without colour; the line is fine and uniform. Makura no Sōshi Emaki, 13th century

Very constructed ink painting, similar to tsukuri-e without colour; the line is fine and uniform. Makura no Sōshi Emaki, 13th century![Landscape in wash. Monochrome version of Saigyō Monogatari Emaki [fr], 15th century](../I/Habukyo_Saigyo_Monogatari_Emaki_-_travel.jpg.webp) Landscape in wash. Monochrome version of Saigyō Monogatari Emaki, 15th century

Landscape in wash. Monochrome version of Saigyō Monogatari Emaki, 15th century Constructed ink painting, Hakubyō Genji Monogatari Emaki, monochrome version of The Tale of Genji, 16th century

Constructed ink painting, Hakubyō Genji Monogatari Emaki, monochrome version of The Tale of Genji, 16th century

Transitions between scenes

The juxtaposition of the text and the painting constitutes a key point of the narrative aspect of emakimono. Originally, in the illustrated sutras, the image was organized in a long, continuous frieze at the top of the scroll, above the texts. That approach, however, was quickly abandoned for a more open layout, of which there are three types:[110]

- Alternation between texts and paintings (danraku-shiki), the former endeavouring to transcribe the illustrations chosen by the artist. Court style paintings (onna-e) often opted for this approach, as paintings more readily focused on important moments or conveyed a narrative.[69][95]

- Intermittence, where the texts appeared only at the beginning or at the end of the scroll, giving pride of place to continuous illustrations (rusōgata-shiki or renzoku-shiki). This type was often used in epic and historical chronicles; the best-known examples are the Shigisan Engi Emaki and the Heiji Monogatari Emaki.[69] Sometimes, the texts were even hosted by a separate handscroll.

- Paintings interspersed with text, i.e. the text was placed above the people who were speaking, as in the Buddhist accounts of the Dōjō-ji Engi Emaki, the Kegon Gojūgo-sho Emaki or the Tengu Zōshi Emaki.

The balance between texts and images thus varied greatly from one work to another. The author had a broad "syntax of movement and time" which allowed him to adapt the form to the story and to the feelings conveyed.[110] The scrolls with continuous illustrations (rusōgata-shiki) naturally made the transitions more ambiguous, because each reader can reveal a larger or smaller portion of the paintings, more or less quickly. In the absence of clear separation between scenes, the mode of reading must be suggested in the paintings in order to maintain a certain coherence.

Two kinds of links between scenes were used by the artists. First, there were links by separation using elements of the scenery (traditionally, river, countryside, mist, buildings) were very common. Secondly, the artists used a palette of transitional elements suggested by the figures or the arrangement of objects. Thus, it was not uncommon for characters to point the finger at the following painting or for them to be represented travelling to create the link between two cities, or for the buildings to be oriented to the left to suggest departure and to the right to suggest the arrival. More generally, Bauer identifies the notion of off-screen (the part of painting not yet visible) that the painter must bring without losing coherence.[111]

- Transitions between texts and paintings: extracts

![Painting in frieze above the text, a form of Chinese origin that was quickly abandoned, Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect [fr], 8th century](../I/E_innga_kyo.jpg.webp) Painting in frieze above the text, a form of Chinese origin that was quickly abandoned, Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect, 8th century

Painting in frieze above the text, a form of Chinese origin that was quickly abandoned, Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect, 8th century![Text before the painting, Obusuma Saburo Emaki [fr], 8th century](../I/Obusuma_Saburo_emaki_-_part_13.jpg.webp) Text before the painting, Obusuma Saburo Emaki, 8th century

Text before the painting, Obusuma Saburo Emaki, 8th century![Text located in a box at the top of the scroll, Kegon Gojūgo-sho Emaki [fr], 12th century](../I/Kegon_Goj%C5%ABgo-sho_Emaki_(Todaiji).jpg.webp) Text located in a box at the top of the scroll, Kegon Gojūgo-sho Emaki, 12th century

Text located in a box at the top of the scroll, Kegon Gojūgo-sho Emaki, 12th century Scene in which the characters' words are written directly in the painting, above them, Kegon Engi Emaki, 13th century

Scene in which the characters' words are written directly in the painting, above them, Kegon Engi Emaki, 13th century

- Transitions between texts and paintings: complete scrolls

Alternation between text and painting – Hell Scroll of Nara National Museum, 12th century

Alternation between text and painting – Hell Scroll of Nara National Museum, 12th century Succession of painted scenes without textual demarcation – Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, 12th century

Succession of painted scenes without textual demarcation – Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, 12th century Succession of painted scenes, with only two sections of text at the beginning and at the end – Heiji Monogatari Emaki, 13th century

Succession of painted scenes, with only two sections of text at the beginning and at the end – Heiji Monogatari Emaki, 13th century

Perspective and point of view

The space in the composition of an emakimono constitutes a second important instance of the narration over time. As the scroll is usually read from right to left and top to bottom, the authors mainly adopt plunging points of view (chōkan, 'bird's-eye perspective'). However, the low height of the emakimono forces the artist to set up tricks such as the use of long diagonal vanishing lines or sinuous curves suggesting depth.[110] Indoors, it is the architectural elements (beams, partitions, doors) that are used to set up these diagonals; outdoors, the diagonals are set up by the roofs, walls, roads and rivers, arranged on several planes. In emakimono painting there is no real perspective in the Western sense – one that faithfully represents what the eye perceives – but, rather, a parallel or oblique projection.[105]

The arrangement of the elements in an emakimono scene is based on the point of view, including the technique known as fukinuki yatai. As mentioned above, scenes are most commonly painted when viewed from above (bird's eye view) in order to maximize the space available for painting, despite the reduced height of the scrolls, while leaving part of the background visible.[112]

In the interior scenes, the simplest technique was developed by from the Chinese Tang artists: only three walls of the room are drawn, in parallel perspective; the point of view is located in the place of the fourth wall, a little higher up. When the need to draw several planes – for example the back of the room or a door open to the next one – arose, the artists proceeded by reducing the size (of the scale).[113] The more general scenes in which the story evolves, such as landscapes, can be rendered from a very distant point of view (as in the Ippen Shōnin Eden or the Sumiyoshi Monogatari Emaki).[114] In the Eshi no Soshi Emaki and the Kokawa-dera Engi Emaki, the painter opted mainly for a side view, and the development of the story depends on a succession of communicating planes.[67]

However, the Japanese artists imagined a new arrangement for emakimono which quickly became the norm for portraying interiors. It was called fukinuki yatai (literally, 'roof removed'), and involves not representing the roofs of buildings, and possibly the walls in the foreground if necessary, to enable a depiction of the interior.[115] Unlike the previous arrangement, the point of view located outside the buildings, still high up, because the primary purpose of fukinuki yatai is to represent two separate narrative spaces – for example two adjoining rooms, or else inside and outside.[113] The genesis of this technique is still little known (it already appears in the biography on wooden panel of Prince Shōtoku),[115] but it already appeared with great mastery on the Court style paintings (onna-e) in the 12th century.

In the Genji Monogatari Emaki, the composition is closely linked to the text and indirectly suggests the mood of the scene. When Kaoru visits Ukifune, while their love is emerging, the artist shows the reader two narrative spaces thanks to the fukinuki yatai: on the veranda, Kaoru is calm, posed in a peaceful space; inside the building, by contrast, Ukifune and her ladies-in-waiting, are painted on a smaller surface, in turmoil, in a confused composition which reinforces their agitation.[113] More generally, an unrealistic composition (for example from two points of view) makes it possible to suggest strong or sad feelings.[116]

The fukinuki yatai technique was also used in a variety of other ways, for example with a very high point of view to reinforce the partitioning of spaces, even in a single room, or by giving the landscape a more important place. Ultimately, the primary goal remained to render two narrative stages, and therefore two distinct spaces, in the same painting.[113] Fukinuki yatai was therefore used extensively, sometimes even as a simple stylistic instance unrelated to feelings or text, unlike in the Genji Monogatari Emaki.[113]

Finally, the scale of an emakimono also makes it possible to suggest depth and guide the arrangement of the elements. In Japanese painting, the scale depends not only on the depth of the scene, but also often on the importance of the elements in the composition or in the story, unlike the realistic renderings in Chinese landscape scrolls. Thus, the main character can be enlarged compared with the others, depending on what the artist wants to express: in the Ippen Shōnin Eden, Ippen is sometimes depicted in the background in a landscape the same size as trees or buildings, so that the reader can clearly identify it. Changes in scale can also convey the mood of the moment, such as the strength of will and distress of Sugawara no Michizane in the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki. For Saint-Marc, "each element takes [more generally] the importance it has in itself in the painter's mind", freeing itself from the rules of realistic composition.[105]

- Perspective techniques

Long vanishing line guiding eye movement, Shigisan Engi Emaki, 12th century

Long vanishing line guiding eye movement, Shigisan Engi Emaki, 12th century Scene in which depth is carried by parallel diagonals (here architecture), without perspective, Genji Monogatari Emaki, 12th century

Scene in which depth is carried by parallel diagonals (here architecture), without perspective, Genji Monogatari Emaki, 12th century![Example of a simple transition using a watercourse, Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect [fr], 8th century](../I/Illustrated_Sutra_of_Cause_and_Effect2.JPG.webp) Example of a simple transition using a watercourse, Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect, 8th century

Example of a simple transition using a watercourse, Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect, 8th century Interior view, in which the roof is not shown (fukinuki yatai). Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, 12th century

Interior view, in which the roof is not shown (fukinuki yatai). Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, 12th century![Interior view of Taima-dera, where the spaces are set aside to show several stages of the story, thanks to the fukinuki yatai. Taima Mandala Engi [fr], 13th century](../I/Taima_mandala_engi_-_weaving.png.webp) Interior view of Taima-dera, where the spaces are set aside to show several stages of the story, thanks to the fukinuki yatai. Taima Mandala Engi, 13th century

Interior view of Taima-dera, where the spaces are set aside to show several stages of the story, thanks to the fukinuki yatai. Taima Mandala Engi, 13th century Scale variation, where the main character appears very tall compared with the mountain; opaque mists are also characteristic of Asian art. Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, 1219

Scale variation, where the main character appears very tall compared with the mountain; opaque mists are also characteristic of Asian art. Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, 1219

Narrative rhythm

The narrative rhythm of emakimono arises mainly from the arrangement between texts and images, which constitutes an essential marker of the evolution of the story. In Court style paintings (onna-e), the artist could suggest calm and melancholy via successions of fixed and contemplative shots, as, for example, in the Genji Monogatari Emaki, in which the scenes seem to be out of time, punctuating moments of extreme sensibilities.[32] By contrast, more dynamic stories play on the alternation between close-ups and wide panoramas, elisions, transitions and exaggeration.[3] In such stories, the narrative rhythm is devoted entirely to the construction of the scroll leading to the dramatic or epic summit, with continuously painted scrolls allowing the action to be revealed as it goes by intensifying the rhythm, and therefore the suspense.[117] The burning of Sanjō Palace in the Heiji Monogatari Emaki illustrates this aspect well, as the artist, by using a very opaque red spreading over almost the entire height of the paper, depicts a gradual intensification of the bloody battles and the pursuit of Emperor Go-Shirakawa until the palace catches fire.[56] Another famous fire, the Ōtenmon Incident in the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, adopts the same approach, by portraying the movements of the crowd, more and more dense and disorderly, until the revelation of the drama.[118][39]

Japanese artists also use other composition techniques to energize a story and set the rhythm: the same characters are represented in a series of varied sets (typically outdoors), a technique known as repetition (hampuku byōsha).[119] In the Gosannen Kassen Ekotoba, a composition centered on Kanazawa Castle gradually shows the capture of the castle by the troops of Minamoto no Yoshiie, creating a gradual and dramatic effect.[120] In the Kibi Daijin Nittō Emaki, the tower to which Kibi no Makibi (or Kibi Daijin) is assigned is painted to depict each challenge won by the protagonist.[121]

Another narrative technique characteristic of emakimono is called iji-dō-zu: it consists of representing the same character several times in a single scene, in order to suggest a sequence of actions (fights, discussions, trips) with great space savings.[105] The movement of the eye is then most often circular, and the scenes portray different moments. Iji-dō-zu can equally suggest either a long moment in one scene, such as the nun in the Shigisan Engi Emaki who remains in retreat in Tōdai-ji for several hours, or a series of brief but intense actions, such as the fights in the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba and the Ippen Shōnin Eden.[119][105] In the Kegon Engi Emaki, the artist offers a succession of almost "cinematographic" shots alternately showing the distress of Zenmyō, a young Chinese girl, and the boat carrying her beloved away on the horizon.[122]

- Narrative techniques

![Scene using the iji-dō-zu technique: the group of demons is first depicted burning below, then listening to the sermons of the historical Buddha in the middle, and finally drinking and reaching the heavens above. Gaki Zōshi [fr], 12th century](../I/Hungry_Ghosts_Scroll_Kyoto_5.jpg.webp) Scene using the iji-dō-zu technique: the group of demons is first depicted burning below, then listening to the sermons of the historical Buddha in the middle, and finally drinking and reaching the heavens above. Gaki Zōshi, 12th century

Scene using the iji-dō-zu technique: the group of demons is first depicted burning below, then listening to the sermons of the historical Buddha in the middle, and finally drinking and reaching the heavens above. Gaki Zōshi, 12th century.jpg.webp) Iji-dō-zu: the nun is depicted alternately praying and sleeping to suggest the length of her retreat. Shigisan Engi Emaki, 12th century

Iji-dō-zu: the nun is depicted alternately praying and sleeping to suggest the length of her retreat. Shigisan Engi Emaki, 12th century Iji-dō-zu: two children fight in the centre under the amused eyes of the crowd, then the father of one of them runs up to the left, and unceremoniously expels his son's rival. Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, 12th century

Iji-dō-zu: two children fight in the centre under the amused eyes of the crowd, then the father of one of them runs up to the left, and unceremoniously expels his son's rival. Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, 12th century

Calligraphy

_1.jpg.webp)

As noted in the history section above, the emergence of the kana syllabary contributed to the development of women's court literature and, by extension, the illustration of novels on scrolls. Kana were therefore used on emakimono, although the Chinese characters remained very much also in use. In some particular scrolls, other alphabets can be found, notably Sanskrit on the Hakubyō Ise Monogatari Emaki.[113]

In East Asia, calligraphy is a predominant art that aristocrats learn to master from childhood, and styles and arrangements of characters are widely codified, although varied. In the context of emakimono, calligraphic texts can have several purposes: to introduce the story, to describe the painted scenes, to convey religious teachings or to be presented in the form of poems (waka poetry remains the most representative of ancient Japan). For the richly decorated court-style paintings (onna-e), like the Genji Monogatari Emaki, the papers were carefully prepared and decorated with gold and silver dust.[123]

The text of an emakimono had more than merely a function of decoration and narration; it could also influence the composition of the paintings. The Genji Monogatari Emaki have been widely studied on this point: art historians have shown a link between the feeling conveyed by a text and the dominant colour of the accompanying paint, a colour which is also used for the decorated paper.[31][124] In addition, the composition of the paintings may make it possible to understand them in accordance with the text: for example, the characters in the story may have been painted on a scene in a palace in the order of their appearance in the text. Other specialists in turn have insisted on the importance of the text in the positioning of the paintings, an important point in the Buddhist emakimono, in which the transmission of dogmas and religious teachings remained an essential goal of the artist.

A Japanese art

According to Peter C. Swann, the production of emakimono was Japan's first truly original artistic movement since the arrival of foreign influences.[125] China's influence in emakimono and pictorial techniques remained tangible at the beginning, so much so that historians have worked to formalise what really constitutes emakimono art as Japanese art. In addition to the yamato-e style, specialists often put forward several elements of answers: the very typical diagonal composition, the perspective depending on the subject, the process of izi-dō-zu, the sensitivity of colours (essential in yamato-e), the stereotypical faces of the characters (impersonal, realistic or caricatured), and finally the hazy atmosphere.[93] K. Chino and K. Nishi also noted the technique of fukinuki yatai (literally, 'roof removed'), unprecedented in all Asian art.[112] Saint-Marc commented that some of these elements actually existed previously in Chinese painting, and that the originality of emakimono was in the overall approach and themes established by the Japanese artists.[126]

The originality of art is also to be sought in its spirit, "the life of an era translated into formal language".[127] The court style paintings (onna-e) are part of the aesthetic of mono no aware (literally 'the pathos of things'), a state of mind that is difficult to express, but which can be regarded as a penchant for sad beauty, the melancholy born of the feeling that everything beautiful is impermanent. D. and V. Elisseeff define this aspect of emakimono as the oko, the feeling of inadequacy, often materialized by a properly Japanese humour. But outside the court, the popular style emakimono (otoko-e), the art of everyday life, come closer to the human and universal state of mind.[127]

Historiographical value

Depiction of everyday Japanese life

Sustained production of emakimono through the Heian, Kamakura and Muromachi periods (about 12th–14th centuries) created an invaluable source of information on the then-contemporary Japanese civilization. Emakimono have been greatly studied in that respect by historians;[128] no other form of Japanese art has been so intimately linked to the life and culture of the Japanese people.[129]

A large project of the Kanagawa University made a very exhaustive study of the most interesting paintings across fifteen major categories of elements, including dwellings, elements of domestic life and elements of life outside the home, according to ages (children, workers, old people) and social class.[lower-alpha 2][130][131] Although the main characters are most often nobles, famous monks or warriors, the presence of ordinary people is more or less tangible in an immense majority of works, allowing a study of a very wide variety of daily activities: peasants, craftsmen, merchants, beggars, women, old people and children can appear in turn.[132][133] In the Shigisan Engi Emaki, the activity of women is particularly interesting, the artist showing them preparing meals, washing clothes or breastfeeding.[130] The Sanjūni-ban Shokunin Uta-awase Emaki presents 142 artisans from the Muromachi period, ranging from a blacksmith to a sake maker.[128]

The clothing of the characters in emakimono are typically true-to-life and accurately depict contemporary clothing and its relationship to the social categories of the time.[134] In military-themed scrolls, the weapons and armour of the warriors are also depicted with accuracy; the Heiji Monogatari Emaki, for instance, depicts many details, in particular the armour and harnesses of horses,[135] whilst the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba depicts the fighting styles of the Japanese during the Mongol invasions of Japan, whose tactics were still dominated by the use of the bow.[136][133] Finally, the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba offers a unique insight into certain details of the uniforms of police officers (known as kebiishi).

The aesthetics, alongside the rendering of people's emotions and expressions of feelings, also show a distinct cleavage between the common people and the aristocracy. For emakimono depicting commoners, emotions such as fear, anguish, excitement and joy are rendered directly and with clarity, whereas aristocratic emakimono instead emphasise refined, but less direct, themes such as classical romance, the holding of ceremonies, and nostalgia for the Heian period.

Historical, cultural and religious reflection