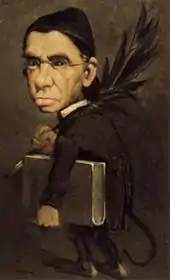

Émile Littré

Émile Maximilien Paul Littré (French: [litʁe]; 1 February 1801 – 2 June 1881) was a French lexicographer, freemason[1] and philosopher, best known for his Dictionnaire de la langue française, commonly called le Littré.

Biography

Littré was born in Paris. His father, Michel-François Littré, had been a gunner and, later, a sergeant-major of marine artillery in the French navy who was deeply imbued with revolutionary ideas of the day. Settling down as a tax collector, he married Sophie Johannot, a free-thinker like himself, and devoted himself to the education of his son Émile. The boy was sent to the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, where Louis Hachette and Eugène Burnouf became his friends. After he completed his studies at the lycée, he was undecided as to what career he should adopt; however, he devoted himself to mastering the English and German languages, classical and Sanskrit literature, and philology.[2]

He finally decided to become a student of medicine in 1822. He passed all his examinations in due course, and had only his thesis to prepare in order to obtain his degree as doctor when, in 1827, his father died leaving his mother without means. He abandoned his degree at once despite his keen interest in medicine, and, while attending lectures by Pierre Rayer, began teaching Latin and Greek to earn a living. He served as a soldier for the populists during the July Revolution of 1830, and was one of the members of the National Guard who followed Charles X to Rambouillet. In 1831, he obtained an introduction to Armand Carrel, the editor of Le National, who gave him the task of reading English and German papers for excerpts. By chance, in 1835, Carrel discovered Littré's skills as a writer and from that time on, he was a constant contributor to the journal, eventually becoming its director.[3]

In 1836, Littré began to contribute articles on a wide range of subjects to the Revue des deux mondes, and in 1837, he married. In 1839, the first volume of his complete works of Hippocrates appeared in print. Due to the outstanding quality of this work, he was elected to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in the same year. He noticed the works of Auguste Comte, the reading of which formed, as he himself said, "the cardinal point of his life." From this time forward, the influence of positivism affected his own life, and, what is of more importance, he influenced positivism, giving as much to this philosophy as he received from it. He soon became a friend of Comte, and popularised his ideas in numerous works on the positivist philosophy. He continued translating and publishing his edition of Hippocrates' writings, which was not completed until 1862, and he published a similar edition of Pliny's Natural History. After 1844, he took Fauriel's place on the committee engaged to produce the Histoire littéraire de la France, where his knowledge of the early French language and literature was invaluable.[4]

Littré started work on his great Dictionnaire de la langue française in about 1844, which was not to be completed until thirty years later. He participated in the revolution of July 1848, and in the repression of the extreme Republican Party in June 1849. His essays, contributed during this period to the National, were collected together and published under the title of Conservation, revolution et positivisme in 1852, and show a thorough acceptance of all the doctrines propounded by Comte. However, during the later years of his master's life, he began to perceive that he could not wholly accept all the dogmas or the more mystic ideas of his friend and master. He concealed his differences of opinion, and Comte failed to recognise that his pupil had outgrown him, as he himself had outgrown his master Henri de Saint-Simon.[4]

Comte's death in 1858 freed Littré from any fear of alienating his master. He published his own ideas in his Paroles de la philosophie positive in 1859. Four years later, in a work of greater length, he published Auguste Comte et la philosophie positive, which traces the origin of Comte's ideas through Turgot, Kant, and Saint-Simon. The work eulogises Comte's own life, his method of philosophy, his great services to the cause and the effect of his works, and proceeds to show where he himself differs from him. He approved wholly of Comte's philosophy, his great laws of society and his philosophical method, which indeed he defended warmly against John Stuart Mill. However, he stated that, while he believed in a positivist philosophy, he did not believe in a "religion of humanity".[4]

About 1863, after completing his translations of Hippocrates and his Pliny, he began work in earnest on his great French dictionary. He was invited to join the Académie française, but declined, not wishing to associate himself with Félix Dupanloup, bishop of Orléans, who had denounced him as the head of the French materialists in his Avertissement aux pères de famille. At this time, he also started La Revue de philosophie positive with Grégoire Wyrouboff, a magazine that embodied the views of modern positivists.[4]

Thus, his life was absorbed in literary work until the events that overthrew the Second Empire called him to take a part in politics. He felt himself too old to undergo the privations of the Siege of Paris, and retired with his family to Brittany. He was summoned by Gambetta to Bordeaux to lecture on history, and thence to Versailles to take his seat in the senate to which he had been chosen by the département of the Seine. In December 1871, he was elected a member of the Académie française in spite of the renewed opposition of Msgr. Dupanloup, who resigned his seat rather than receive him.[4]

Littré's Dictionnaire de la langue française ("Dictionary of the French Language") was completed in 1873 after nearly 30 years of work. The draft was written on 415,636 sheets, bundled in packets of one thousand, stored in eight white wooden crates that filled the cellar of Littré's home in Mesnil-le-Roi. The landmark effort gave authoritative definitions and usage descriptions to every word based on the various meanings it had held in the past. When it was published by Hachette, it was the largest lexicographical work on the French language at that time.

In 1874, Littré was elected Senator for life of the Third Republic.[5] His most notable writings during these years were his political papers that attacked and revealed the confederacy of the Orléanists and Legitimists against the Republic; his re-editions of many of his old articles and books, among others the Conservation, révolution et positivisme of 1852 (which he reprinted word for word, appending a formal, categorical renunciation of many of the Comtist doctrines therein contained); and a little tract, Pour la dernière fois, in which he maintained his unalterable belief in the philosophy of Materialism.[4]

In 1875, he applied for membership in the Masonic Lodge La Clémente Amitié (Grand Orient de France). When asked whether he believed in the existence of a supreme being in the presence of 1000 Freemasons, he replied:

A wise man of ancient times, who was asked the same question by a king, thought about an answer for days, but was never able to answer. I please you not to request an answer from me. No science denies a "first cause", because it finds neither another warrant nor proof. All knowledge is relative and we always meet unknown phenomena and laws we don't know its cause. The one who proclaims with determination to neither believe nor disbelieve in a God proofs not to understand the problem of what makes things exist and disappear.[6]

When it became obvious that the old man would not live much longer, his wife and daughter, who had always been fervent Catholics, strove to convert him to their religion. He had long discussions with Father Louis Millériot, a celebrated Controversialist, and Abbé Henri Huvelin, the noted priest of Église Saint-Augustin, who were much grieved at his death. When Littré was near death, he converted, was baptised by the abbé and his funeral was conducted with the rites of the Roman Catholic Church.[4][7][8] Littré is interred at Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

Works

Translations and re-editions

- Translation of the complete works of Hippocrates (1839–1863)

- Translation of Pliny's Natural History (1848–1850)

- Translation of Strauss's Vie de Jésus (1839–1840)

- Translation of Müller's Manuel de physiologie (1851)

- Re-edition of the political writings of Armand Carrel, with notes (1854–1858)

Dictionaries and writings on language

- Reprise du Dictionnaire de médecine, de chirurgie, etc. with Charles-Philippe Robin, of Pierre-Hubert Nysten (1855)

- Histoire de la langue française a collection of magazine articles (1862)

- Dictionnaire de la langue française ("Le Littré") (1863–1873)

- Comment j'ai fait mon dictionnaire (1880)

Philosophy

- Analyse raisonnée du cours de philosophie positive de M. A. Comte (1845)

- Application de la philosophie positive au gouvernement (1849)

- Conservation, révolution et positivisme (1852, 2nd ed., with supplement, 1879)

- Paroles de la philosophie positive (1859)

- Auguste Comte et la philosophie positive (1863)

- La Science au point de vue philosophique (1873)

- Fragments de philosophie et de sociologie contemporaine (1876)

Other works

- Études et glanures (1880)

- La Verité sur la mort d'Alexandre le grand (1865)

- Études sur les barbares et le moyen âge (1867)

- Médecine et médecins (1871)

- Littérature et histoire (1875)

- Discours de reception à l'Académie française (1873)

References

- Dictionnaire universel de la Franc-Maçonnerie by Monique Cara, Jean-Marc Cara, Marc de Jode (Larousse, 2011).

- Chisholm 1911, p. 794.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 794–795.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 795.

- Delamarre, Louis Narcisse (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9.

- Eugen Lennhoff, Oskar Posner, Dieter A. Binder: Internationales Freimaurer Lexikon. 5. Auflage, Herbig Verlag, p. 299, 519-520. ISBN 978-3-7766-2478-6.

- Christopher Clark; Wolfram Kaiser (2003). Culture Wars: Secular-Catholic Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-139-43990-9.

- The Death-bed of a Positivist, The New York Times, 19 June 1881

Sources

- For his life consult C.A. Sainte-Beuve, Notice sur M. Littré, sa vie et ses travaux (1863); and Nouveaux Lundis, vol. v.; also the notice by M. Durand-Gréville in the Nouvelle Revue of August 1881; E Caro, Littré et le positivisme (1883); Pasteur, Discours de récéption at the Academy, where he succeeded Littré, and a reply by Ernest Renan.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Littré, Maximilien Paul Émile". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 794–795.

Further reading

- (in French) Jean Hamburger, Monsieur Littré, Flammarion, Paris, 1988

External links

- Works by Emile Littré at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Émile Littré at Internet Archive

- Collection Medic@ offers Littré's edition of Hippocrates, complete in scanned page images

- Delamarre, Louis Narcisse (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9.

- (in French) Dictionnaire de la langue française Littré (1863–1876)