Endemic COVID-19

COVID-19 is predicted to become an endemic disease by many experts. The observed behavior of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, suggests it is unlikely it will die out, and the lack of a COVID-19 vaccine that provides long-lasting immunity against infection means it cannot immediately be eradicated;[1] thus, a future transition to an endemic phase appears probable. In an endemic phase, people would continue to become infected and ill, but in relatively stable numbers.[1] Such a transition may take years or decades.[2] Precisely what would constitute an endemic phase is contested.[3]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

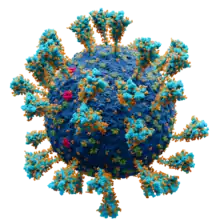

Scientifically accurate atomic model of the external structure of SARS-CoV-2. Each "ball" is an atom. |

|

|

|

COVID-19 endemicity is distinct from the COVID-19 public health emergency of international concern, which was ended by the World Health Organization on May 5, 2023.[4] Endemic is a frequently misunderstood and misused word outside the realm of epidemiology. Endemic does not mean mild, or that COVID-19 must become a less hazardous disease. Some politicians and commentators have conflated what they termed endemic COVID-19 with the lifting of public health restrictions or a comforting return to pre-pandemic normality.

The severity of endemic disease would be dependent on various factors, including the evolution of the virus, population immunity, and vaccine development and rollout.[2][5][6]

Definition and characteristics

An infectious disease is said to be endemic when the number of infections is predictable.[7] This includes diseases with infection rates that are predictably high (called hyperendemic), as well as diseases with infection rates that are predictably low (called hypoendemic).[7] Endemic does not mean mild: a disease with a stable infection rate can be associated with any level of disease severity and any mortality rate among infected people.[8] Endemic COVID-19 is not a synonym for COVID-19 infection becoming safe, or for mortality and morbidity becoming less of a problem. The prevalence and resulting disease burden is dependent on factors such as how quickly new variants emerge, the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, and changes to disease virulence (a factor that depends on both the virus's own characteristics and people's immunity against it), rather than being dependent on endemicity.[2]

Generally speaking, all new emerging infectious diseases have five potential outcomes:[9]

- Eradication – eventually, the disease dies out completely. This is not expected for COVID-19.[1]

- Sporadic spread – unpredictable individual outbreaks that, due to any combination of factors limiting transmissibility (including changes to people's behavior[10]), tend not to spread out of the immediate chain of infections.[9] This was briefly achieved early in the pandemic in a few smaller countries through rigorous surveillance measures,[11] but it is not an expected outcome for COVID-19 globally.

- Epidemic – also called local or regional spread, this is most commonly the result of some inherent qualities of the infection, such as how soon contagious people become symptomatic, and some behaviors, such as how much contact people have and whether they use any effective non-pharmaceutical interventions to limit spread of the virus.[9][10] This is not expected for COVID-19, as people often become contagious before they develop any symptoms.[9]

- Pandemicity – a global outbreak, often associated with a new pathogen that no one has any immunity against.[9] COVID-19 became a pandemic shortly after the first cases were identified.

- Endemicity – a common outcome for most emerging infections diseases that began with a pandemic phase, including pandemic influenza.[9] Many experts expect COVID-19 to become endemic.[9]

Additionally, if an infectious disease becomes endemic, there is no guarantee that the disease will remain endemic forever. A disease that is usually endemic can become epidemic or pandemic in the future.[9] For example, in some years, influenza becomes a pandemic, even though it is not usually a pandemic.

During the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, it became apparent that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was unlikely to die out.[1] Eradication is widely believed to be impossible, especially in the absence of a vaccine that provides long-lasting immunity against infection from COVID-19.[1]

While all of the other outcomes are possible – sporadic, epidemic, pandemic, or endemic – many experts believe that COVID-19 is most likely to become endemic.[1][9] Endemicity is characterized by continued infections by the virus, but with a more stable, predictable number of infected people than in the other three categories.

There is no single agreed definition or metric that proves that COVID-19 has become endemic.[12]

Endemic epidemiology

A March 2022 review said that it was "inevitable" the SARS-CoV-2 virus would become endemic to humans, and that it was essential to develop public health strategies to anticipate this.[5] A June 2022 review predicted that the virus that causes COVID-19 would become the fifth endemic seasonal coronavirus, alongside four other human coronaviruses.[6] A February 2023 review of the four common cold coronaviruses concluded that the virus would become seasonal and, like the common cold, cause less severe disease for most people.[13]

As of 2023 it was thought a transition to endemic COVID-19 could take years or decades.[2]

Determinants

The largest determinant of how endemicity manifests is the level of immunity people have acquired, either as a result of vaccination or of direct infection.[1] The severity of a disease in an endemic phase depends on how long-lasting immunity against severe outcomes is. If such immunity is lifelong, or lasts longer than immunity against re-infection, then re-infections will mostly be mild, resulting in a endemic phase with mild disease severity.[1] In other existing human coronaviruses, protection against infection is temporary, but observed reinfections are relatively mild.[1]

Status as an endemic disease requires a stable level of transmission. Anything that could affect the level of transmission could determine whether the disease becomes and remains endemic, or takes another path. These factors include but are not limited to:[10]

- demographic factors, such as changing population sizes and urbanization, which results in changes to the rate at which people have contact with infected people (COVID-19 outbreaks persist longer in dense urban areas[10]) and ageing populations, which remain contagious longer than young adults;[10]

- changes to the climate, which can cause people to move or to have different exposure risks;[10]

- human behavior, such as people traveling, which could cause new variants of SARS-CoV-2 to spread quickly;[10]

- immunity, including both present and future vaccine-based immunity and infection-based immunity, and

- seasonal fluctuations, such as a tendency to go outside during pleasant weather.[10]

Many of the factors that determine whether COVID-19 becomes endemic are not unique to COVID-19.[10]

Global status

On 5 May 2023, the WHO declared that the pandemic was no longer a public health emergency of international concern. Ghebreyesus stated that the pandemic's downward trend over the preceding year "has allowed most countries to return to life as we knew it before COVID-19", though cautioning that new variants could still pose a threat and that the conclusion of the current state of emergency did not mean that the COVID-19 is no longer a worldwide health concern.[14][15][16]

Culture and society

According to historian Jacob Steere-Williams, what endemicity means has evolved since the 19th century, and the desire to label COVID-19 as being endemic in early 2022 was a political and cultural phenomenon connected to a desire to see the pandemic as being over.[3]

Paleovirologist Aris Katzourakis wrote in January 2022 that the word endemic was one of the most misused of the COVID-19 pandemic.[17]

International Nursing Review journal editor Tracey McDonald warned in a 2023 editorial on endemicity that "Traps for unwary politicians and commentators include statements on scientific matters that fall well outside their knowledge and experience, and the danger of adopting and misusing esoteric terminology that has nuanced meanings within professional circles."[18]

When COVID-19 emerged, most people were unfamiliar with the term endemic.[19] Although the representations of endemic COVID-19 in English-language media reports were decidedly negative during the early weeks of the pandemic, since then, the concept of endemicity has been represented in the media as a positive outcome.[19] English-language media coverage, using endemic more like a buzzword to change the public's view of COVID-19 than according to a strict scientific definition, anchored the concept of endemic COVID-19 to seasonal influenza.[19] By December 2021, endemicity was being represented in media as an opportunity that people should seize to "live with the virus" and achieve a "new normal".[19] People were being told that endemicity was a desirable outcome that would achieve not only actual endemicity (a stable, predictable number of infections), but that would also bring them familiar seasonal patterns of infection, manageable demands on healthcare, and a less virulent, relatively harmless disease.[19]

Media coverage has also objectified endemicity through the metaphor of a journey, especially as the destination at the end of "the path to normality".[19]

See also

- COVID-19 pandemic by country and territory

- Public health mitigation of COVID-19

- Treatment and management of COVID-19

- Law of declining virulence – discredited 19th-century idea that pathogens always become milder over time

References

- Antia R, Halloran ME (October 2021). "Transition to endemicity: Understanding COVID-19". Immunity (Review). 54 (10): 2172–2176. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2021.09.019. PMC 8461290. PMID 34626549.

- Markov PV, Ghafari M, Beer M, Lythgoe K, Simmonds P, Stilianakis NI, Katzourakis A (June 2023). "The evolution of SARS-CoV-2". Nat Rev Microbiol (Review). 21 (6): 361–379. doi:10.1038/s41579-023-00878-2. PMID 37020110. S2CID 257983412.

In the absence of eradication, the virus will likely become endemic, a process that could take years to decades. We will be able to establish that endemic persistence has been reached if the virus shows repeatable patterns in prevalence year on year, for example, regular seasonal fluctuations and no out-of-season peaks. The form this endemic persistence will take remains to be determined, and the eventual infection prevalence and disease burden will depend on the rate of emergence of antigenically distinct lineages, our ability to roll out and update vaccines, and the future trajectory of virulence (Fig. 4c)....Meanwhile, focusing on the epidemiology of the pathogen, it is important to bear in mind that the transition from a pandemic to future endemic existence of SARS-CoV-2 is likely to be long and erratic, rather than a short and distinct switch, and that endemic SARS-CoV-2 is by far not a synonym for safe infections, mild COVID-19 or a low population mortality and morbidity burden.

- Steere-Williams J (May 2022). "Endemic fatalism and why it will not resolve COVID-19". Public Health. 206: 29–30. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2022.02.011. ISSN 0033-3506. PMC 8841151. PMID 35316742.

- "WHO downgrades COVID-19 pandemic, says it's no longer a global emergency". CBC. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- Koelle, Katia; Martin, Michael A.; Antia, Rustom; Lopman, Ben; Dean, Natalie E. (11 March 2022). "The changing epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 375 (6585): 1116–1121. Bibcode:2022Sci...375.1116K. doi:10.1126/science.abm4915. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 9009722. PMID 35271324.

- Cohen, Lily E.; Spiro, David J.; Viboud, Cecile (30 June 2022). "Projecting the SARS-CoV-2 transition from pandemicity to endemicity: Epidemiological and immunological considerations". PLOS Pathogens. 18 (6): e1010591. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1010591. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 9246171. PMID 35771775.

- "Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice, Third Edition An Introduction to Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- Ticona, Eduardo; Gao, George Fu; Zhou, Lei; Burgos, Marcos (13 April 2023). "Person-Centered Infectious Diseases and Pandemics". In Mezzich, Juan E.; Appleyard, James; Glare, Paul; Snaedal, Jon; Wilson, Ruth (eds.). Person Centered Medicine. Springer Nature. p. 465. ISBN 978-3-031-17650-0.

- Cohen, Lily E.; Spiro, David J.; Viboud, Cecile (30 June 2022). "Projecting the SARS-CoV-2 transition from pandemicity to endemicity: Epidemiological and immunological considerations". PLOS Pathogens. 18 (6): e1010591. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1010591. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 9246171. PMID 35771775.

- Baker, Rachel E.; Mahmud, Ayesha S.; Miller, Ian F.; Rajeev, Malavika; Rasambainarivo, Fidisoa; Rice, Benjamin L.; Takahashi, Saki; Tatem, Andrew J.; Wagner, Caroline E.; Wang, Lin-Fa; Wesolowski, Amy; Metcalf, C. Jessica E. (April 2022). "Infectious disease in an era of global change". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 20 (4): 193–205. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00639-z. ISSN 1740-1534. PMC 8513385. PMID 34646006.

- Koelle, Katia; Martin, Michael A.; Antia, Rustom; Lopman, Ben; Dean, Natalie E. (11 March 2022). "The changing epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 375 (6585): 1116–1121. Bibcode:2022Sci...375.1116K. doi:10.1126/science.abm4915. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 9009722. PMID 35271324.

- Duong D (October 2022). "Endemic, not over: looking ahead to a new COVID era". CMAJ. 194 (39): E1358–E1359. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1096021. PMC 9616156. PMID 36220172.

- Harrison, Cameron M.; Doster, Jayden M.; Landwehr, Emily H.; Kumar, Nidhi P.; White, Ethan J.; Beachboard, Dia C.; Stobart, Christopher C. (10 February 2023). "Evaluating the Virology and Evolution of Seasonal Human Coronaviruses Associated with the Common Cold in the COVID-19 Era". Microorganisms. 11 (2): 445. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11020445. ISSN 2076-2607. PMC 9961755. PMID 36838410.

After evaluating the biology, pathogenesis, and emergence of the human coronaviruses that cause the common cold, we can anticipate that with increased vaccine immunity to SARS-CoV-2, it will become a seasonal, endemic coronavirus that causes less severe disease in most individuals. Much like the common cold CoVs, the potential for severe disease will likely be present in those who lack a protective immune response or are immunocompromised.

- "From emergency response to long-term COVID-19 disease management: sustaining gains made during the COVID-19 pandemic". www.who.int. World Health Organization. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Heyward, Giulia; Silver, Marc (5 May 2023). "WHO ends global health emergency declaration for COVID-19". NPR. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Rigby, Jennifer (8 May 2023). "WHO declares end to COVID global health emergency". Reuters. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Katzourakis A (January 2022). "COVID-19: endemic doesn't mean harmless". Nature. 601 (7894): 485. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..485K. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00155-x. PMID 35075305. S2CID 246277859.

- McDonald T (March 2023). "Are we there yet? A guide to achieving endemic status for COVID-19 and variants". Int Nurs Rev (Editorial). 70 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/inr.12823. PMC 9880758. PMID 36571833.

- Nerlich, Brigitte; Jaspal, Rusi (2 June 2023). "From danger to destination: changes in the language of endemic disease during the COVID-19 pandemic". Medical Humanities. doi:10.1136/medhum-2022-012433. ISSN 1468-215X. PMID 37268406. S2CID 259047233.