English Electric

The English Electric Company Limited (EE) was a British industrial manufacturer formed after the armistice ending the fighting of World War I by amalgamating five businesses which, during the war, had been making munitions, armaments and aeroplanes.[1]

| |

| Type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Transport |

| Predecessor | |

| Founded | December 1918 (as The English Electric Company Limited) |

| Defunct | 1968 |

| Fate | Merged with General Electric in 1968 |

| Successor | |

| Headquarters | Strand, London, England, UK |

| Products | |

| Subsidiaries | List

|

It initially specialised in industrial electric motors and transformers, locomotives and traction equipment, diesel motors and steam turbines. Its activities were later expanded to include consumer electronics, nuclear reactors, guided missiles, military aircraft and mainframe computers.

Two English Electric aircraft designs became landmarks in British aeronautical engineering; the Canberra and the Lightning. In 1960, English Electric Aircraft (40%) merged with Vickers (40%) and Bristol (20%) to form British Aircraft Corporation.

In 1968 English Electric's operations were merged with GEC's,[2] the combined business employing more than 250,000 people.[3]

Foundation

Aiming to turn their employees and other assets to peaceful productive purposes, the owners of a series of businesses decided to merge them forming The English Electric Company Limited in December 1918.[1]

Components

English Electric was formed to acquire ownership of:

- Coventry Ordnance Works of Coventry, which retained a separate identity, and their ordnance works at Scotstoun which was later sold to Harland and Wolff in April 1920.

- Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Company of Bradford

- Dick, Kerr & Co. of Preston founded 1880 and its subsidiaries:

- United Electric Car Company of Preston

- Willans & Robinson of Rugby which retained a separate identity—not wholly owned.

The owners of the component companies took up the shares in English Electric.[1]

Planned activities of the combined businesses

John Pybus was appointed managing director in March 1921[4] and chairman in April 1926.[5] Initially J H Mansell of Coventry Ordnance Works, John Pybus of Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing and W Rutherford of Dick, Kerr were joint managing directors.[6]

The five previously independent major operations under their control had these principal capabilities:

- Coventry Ordnance Works: the plant was built for the production of heavy armaments but was suitable for the manufacture of large generating units[6]

- Phoenix Dynamo Works: during the war production was shells and aeroplanes but by July 1919 had been returned to electric motors[6]

- Dick, Kerr and United Electric Car: special war work[6] munitions, aeroplanes and metallic filament lamps, prior to the war locomotives and tram cars

- Willans & Robinson: made steam turbines, condensers and diesel motors, there was a foundry[6]

Together these businesses covered the whole field of electrical machinery from the smallest fan motor to the largest turbo-generator.[6]

In November 1919, English Electric bought the Stafford works of Siemens Brothers Dynamo Works Ltd.[7] In 1931 Stafford became English Electric's centre.[8]

.jpg.webp)

However, there was no post-war boom in electrical generation. Though English Electric products were indeed in heavy demand, potential buyers were unable to raise the necessary capital funds. In 1922, a drastic reorganisation of the works was carried through and that managed to halve overheads. The Coventry Ordnance Works was practically closed down. Cables, lamps and wireless equipment were then in buoyant demand, but that would have been a new field for the company to enter. English Electric's business was in heavy electrical and mechanical plant.[9] Both the 1926 general strike and the miners strike caused heavy losses.[10] In 1929 part of the Coventry Ordnance Works was sold and the pattern shop at Preston, neither of which was required.[11]

By the end of 1929, it was clear the only solution to English Electric's financial difficulties was a financial restructure. The restructure acknowledged the loss of much of the shareholders' capital and brought in new capital to re-equip with new plant and machinery. In the event, an American syndicate fronted by Lazard Brothers and Co. bankers came up with the new capital, but left control in the hands of the previous shareholders.[12]

In June 1930, four fresh directors were appointed, filling four new vacancies.[13]

Ten days later, there was a formal announcement of an American arrangement. "English Electric, with works at Preston, Stafford, Rugby, Bradford and Coventry, had entered into a comprehensive arrangement" with Westinghouse Electric International Company of New York and Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company of East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania US, whereby there would be an exchange of technical information between the two organisations on steam turbines and electrical apparatus. It was made clear that this technical and manufacturing link did not carry with it any control from America. In recognition of the exchange arrangement, Westinghouse had offered to provide further capital, which would be less than 10% of the total, including that new capital organised earlier by Lazard Brothers.[14]

George Nelson

Seven weeks later the chairman, Lionel Hichens, who had temporarily replaced John Pybus in 1927, retired at the end of July 1930 and was replaced by Sir Holberry Mensforth as a director and as chairman.[15] It was then announced that George H. Nelson had been appointed to the board and would take up the position of managing director early in October.[16] Mensforth had been taken away from his position as general manager of American Westinghouse Trafford Park Manchester, where George Nelson had been his apprentice, in 1919 by the Minister of Transport. The minister had given Mensforth the responsibility of easing the transition of the nation's munitions businesses back into peacetime industry. It was Mensforth who had arranged the technical exchange agreement and extra capital with Westinghouse.[17] They began to reorganise.

Relocations

The main base of the company's operation was moved from London to Stafford including the sales departments, general and factory accounts and the principal executives previously in London. The managing director was to divide his time between the various works but would be mainly in Stafford or in London[8]

On 30 December 1930 the engineering shops at Preston closed leaving the following distribution:[8]

- Preston: specialists in high-tension direct-current railway electrification, rolling stock and trolley buses Dick, Kerr

- Stafford: medium-sized electrical plant, transformers and switchgear and (from Preston) large turbo-alternator work Siemens

- Rugby: prime movers, steam turbines and condensing plant, Fullagar and Diesel engines and (from Preston) water turbine plant Willans & Robinson

- Bradford: small motors and control gear and (from Preston) traction motor and traction control work Phoenix

- Coventry: engineers small tools (stopped in 1931), zed fuse (cartridge type) transferred to Stafford in 1931 C.O.W.

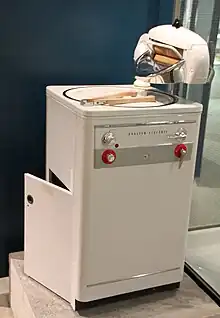

Radiators and cookers

Manufacture of domestic apparatus got underway at both Stafford and Bradford during 1931.[18] They were followed in 1934 by a range of household meters of various kinds. In the same report to shareholders, the chairman pointed out that every day 330 more homes adopted electricity for heating cooking and lighting and between 1929 and 1935 the production of electricity in Britain had increased by 70 per cent.[19]

Recovery

1933 proved to be the first of four years of real achievement. At the beginning of July 1933, Mensforth stepped down and George Nelson took up the post of chairman. Nelson remained managing director.[20] Mensforth kept a seat on the board from which he later retired at the end of 1936.[21]

English Electric's recovery was noted by commentators as remarkable. During 1936, past preference dividends had been brought up to date: they were English Electric's first dividend since a 1924 dividend on ordinary shares. The balance sheet at the end of 1936 showed liquidity was in a strong position[22] and the chairman told shareholders that the rate of production in the factories for the last three months of the year was double the rate of production in the first three months.[23]

During 1938, the first dividend was paid on ordinary shares since 1924.[24]

In the summer of 1938, a large display advertisement confidently declared:

ENGLISH ELECTRIC PLANT AND EQUIPMENT in operation throughout the world.

With its historical achievements and the wealth of experience of its several Associated Companies the English Electric Company

continues to maintain its reputation as Manufacturers and Suppliers of electrical and allied products for Home and Overseas markets:Three English Electric

7SRL Diesel alternator sets being installed

the Saateni Power Station, Zanzibar 1955

- STEAM TURBINES

- WATER TURBINES

- OIL ENGINES

- GENERATORS

- SWITCHGEAR

- TRANSFORMERS

- RECTIFIERS

- ELECTRIC MOTORS

- ELECTRIC AND DIESEL-ELECTRIC TRACTION EQUIPMENTS

- MARINE PROPULSION EQUIPMENT

- DOMESTIC APPLIANCES

- Complete Electrification Schemes Undertaken[25]

World War II

Airframes

The first steps to strengthen the Royal Air Force had been taken in May 1935 and English Electric was brought into the scheme for making airframes[26] working in conjunction with Handley Page.[27] The chairman reported to shareholders that though both Dick, Kerr and Phoenix were involved in the aircraft business during and shortly after the previous war the problems had so changed they were now completely new to the company. He also noted as he ended his address that the demand for domestic appliances including cookers, breakfast cookers, washing machines and water heaters was growing progressively.[28]

The Preston works without subcontracting made more than 3,000 Hampden and Halifax aircraft.[29][30]

Aero engines

_Point_Cook_Vabre.jpg.webp)

In December 1942, English Electric bought the ordinary shares of D. Napier & Son Limited. Mr H G Nelson, son of English Electric chairman George H Nelson, was appointed managing director.[31]

Napier's Sabre engines were used in Typhoon and Tempest aircraft and Lion engines in Motor Torpedo Boats[29][30]

Tanks, locomotives, submarines, ships, power generation

The Stafford works made thousands of Covenanter, Centaur and Cromwell tanks as well as precision instruments for aircraft, electric propulsion and electrical equipment.

The Rugby works made Diesel engines for ships, submarines and locomotives, steam turbines for ships and turbo-alternator sets for power stations.

Bradford made electric generators for ships' auxiliaries and a wide variety of other naval and aviation material.[29][30]

Employees

In April 1945, English Electric employed 25,000 persons in its four main works.[30] Subsequently the chairman revealed that the peak employment number during wartime had been 45,000 when including Napier's people.[32] C. P. Snow was appointed director of scientific personnel in 1944. Later he was physicist-director, a position he held until 1964.[33]

de Havilland Vampire

In September 1945, details were released of the Vampire jet, the fastest British aircraft with a top speed of 548 mph. The aircraft was built by English Electric at its Preston works, the Frank Halford designed Goblin jet engine, the world's most powerful, by de Havilland in London.[34]

Peacetime

Trams

From 1912 to 1924, United Electric and English Electric (with assistance from Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock) supplied second- and third-series tramcars for Hong Kong Tramways. These cars were eventually retired from 1924 to 1930 as the fourth Generation cars were being introduced.

Railways

.jpg.webp)

In 1923, English Electric supplied the EO electric locomotives for the New Zealand Railways for use between Arthurs Pass and Otira, in the Southern Alps. Between 1924 and 1926, they delivered nine box-cab electric (B+B) locomotives to the Harbour Commissioners of Montreal (later the National Harbours Board); later they were transferred to Canadian National Railways, where four of them ran until 1995. In 1927, English Electric delivered 20 electric motor cars for Warsaw's Warszawska Kolej Dojazdowa. During the 1930s, equipment was supplied for the electrification of the Southern Railway system, reinforcing EE's position in the traction market, and it continued to provide traction motors to them for many years.

In 1936, production of diesel locomotives began in the former tramworks in Preston. Between the late 1930s and the 1950s, English Electric supplied electric multiple unit trains for the electrified network in and around Wellington, New Zealand. In 1951 English Electric supplied 3 & 5 car articulated Diesel Electric multiple units to the Egyptian State Railways Egyptian-thumpers. Between 1951 and 1959, English Electric supplied the National Coal Board with five 51-ton, 400 hp electric shunting locomotives for use on the former Harton Coal Company System at South Shields (which had been electrified by Siemens in 1908) to supplement the existing fleet of ten ageing Siemens and AEG locomotives. English Electric took over Vulcan Foundry and Robert Stephenson and Hawthorns, both with substantial railway engineering pedigrees, in 1955.

English Electric produced nearly 1000 diesel and electric locomotives, of nine different classes, for British Rail as part of the Modernisation Plan in the 1950s and 1960s. Most of these classes of locomotive gave long service to British Rail and its successor train operating companies, some still being active well into the 21st century.

Aviation

Both Dick, Kerr & Co. and the Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Company built aircraft in the First World War, including flying boats designed by the Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe, 62 Short Type 184 and 6 Short Bombers designed by Short Brothers. Aircraft manufacture under the English Electric name began in Bradford in 1922 with the Wren but lasted only until 1926 after the last Kingston flying boat was built.

With War in Europe looming, English Electric was instructed by the Air Ministry to construct a "shadow factory" at Samlesbury Aerodrome in Lancashire to build Handley Page Hampden bombers. Starting with Flight Shed Number 1, the first Hampden built by English Electric made its maiden flight on 22 February 1940 and, by 1942, 770 Hampdens had been delivered – more than half of all the Hampdens produced. In 1940, a second factory was built on the site and the runway was extended to allow for construction of the Handley Page Halifax four-engined heavy bomber to begin. By 1945, five main hangars and three runways had been built at the site, which was also home to No. 9 Group RAF. By the end of the war, over 2,000 Halifaxes had been built and flown from Samlesbury.

In 1942, English Electric took over D. Napier & Son, an aero-engine manufacturer. Along with the shadow factory, this helped to re-establish the company's aeronautical engineering division. Post-war, English Electric invested heavily in this sector, moving design and experimental facilities to the former RAF Warton near Preston in 1947. This investment led to major successes with the Lightning and Canberra, the latter serving in a multitude of roles from 1951 until mid-2006 with the Royal Air Force.

At the end of the war, English Electric started production under licence of the second British jet fighter, the de Havilland Vampire, with 1,300 plus built at Samlesbury. Their own design work took off after the Second World War under W. E. W. Petter, formerly of Westland Aircraft. Although English Electric produced only two aircraft designs before their activities became part of BAC, the design team put forward suggestions for many Air Ministry projects.

The aircraft division was formed into the subsidiary English Electric Aviation Ltd. in 1958, becoming a founding constituent of the new British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) in 1960; English Electric having a 40% stake in the latter company. The guided weapons division was added to BAC in 1963.

Industrial Electronics

The Industrial Electronics Division was established at Stafford. One of the products produced at this branch was the Igniscope, a revolutionary design of ignition tester for petrol engines. This was invented by Napiers and supplied as Type UED for military use during World War 2. After the war, it was marketed commercially as type ZWA.[35]

Mergers, acquisitions and demise

In 1946, English Electric took over the Marconi Company, a foray into the domestic consumer electronic market. English Electric tried to take over one of the other major British electrical companies, the General Electric Company (GEC), in 1960 and, in 1963, English Electric and J. Lyons and Co. formed a jointly owned company – English Electric LEO Company – to manufacture the LEO computer developed by Lyons.

English Electric took over Lyons' half-stake in 1964 and merged it with Marconi's computer interests to form English Electric Leo Marconi (English Electric LM). The latter was merged with Elliott Automation and International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) to form International Computers Limited (ICL) in 1967.[36] In 1968 GEC, recently merged with Associated Electrical Industries (AEI), merged with English Electric; the former being the dominant partner, the English Electric name was then lost.

Some products

Electrical machinery

Complete electrification schemes

- Polish State Railways

- London Post Office Railway, London Post Office Railway 1927 Stock and London Post Office Railway 1962 Stock

- Wellington N.Z. suburban railway system

Steam turbines

- Munmorah Power Station

- Churchill-class submarines

- St. Laurent-class destroyers - originally by licensee John Inglis and Company)

- Restigouche-class destroyers

- Hinkley Point A nuclear power station, Hartlepool Nuclear Power Station, Wylfa Nuclear Power Station, Sizewell nuclear power stations

Water turbines

Oil engines Generators

- Ultimo Power Station

- Tallawarra Power Station

- Monowai Power Station

- White Bay Power Station

- Blyth Power Station

Switchgear, transformers, rectifiers

Electric motors

Electric and Diesel-electric traction equipment

- Blackpool tramway, English Electric Balloon tram

- New Zealand Railways Department see Diesel Traction Group (NZ)

Marine Propulsion equipment

Domestic appliances

Military equipment

Aircraft

- English Electric P.5 Phoenix "Cork" (1918)[37]

- Wren (1923)

- Ayr (1923)

- Kingston (1924)

- Canberra (1949)

- English Electric P1A (Lightning prototype)

- Lightning (1954)

- English Electric P.10 (unbuilt supersonic bomber to OR.330/R.156).[38]

Manned spacecraft

Guided weapons

- Thunderbird (1959) – surface-to-air missile

- Blue Water (cancelled 1962) – short-range ballistic missile

Tanks

Computers

- Luton Analogue Computing Engine

- English Electric DEUCE (1955)

- English Electric KDN2

- English Electric KDF6

- English Electric KDF8

- English Electric KDF9 (1963)

- English Electric KDP10

- English Electric System 4 (1965) – the System 4–50 and System 4–70 were based on the RCA Spectra 70 series, built under licence. The latter were almost the same as IBM System /360 range, differing only in their real-time facilities, with four processor states and multiple sets of general-purpose registers.

Railways and traction

Engines

- English Electric 6CSRKT diesel

- English Electric 6SRKT diesel

- English Electric 8SVT 1000 hp (fitted to Class 20)

- English Electric 8CSV 1050 hp (at 750 rev/min - Typically used for Generation)

- English Electric 12SVT 1470 hp (retro-fitted to Class 31)

- English Electric 12CSVT 1750 hp (fitted to Class 37)

- English Electric 12CSV

- English Electric 16SVT 2000 hp (Mk II version fitted to Class 40)

- English Electric 16CSVT 2700 hp (fitted to Class 50)

- The 3250 hp Ruston Paxman 16RK3CT fitted to the Class 56's was effectively an improved version of the Class 50 16CSVT power unit.

- Napier Deltic (Makers D. Napier and Son were an English Electric subsidiary company from 1942)

Locomotives and multiple units

- CGR class S1

- Ceylon Government Railway Class T1

- Indian locomotive class WCM-1

- Indian locomotive class WCM-2

- British Rail Class 08

- British Rail Class 09

- British Rail Class 11

- British Rail Class 12

- British Rail Class 13 (modified Class 08 shunters semi-permanently coupled in pairs)

- English Electric Type 1 (British Rail Class 20)

- English Electric Type 2 (British Rail Class 23)

- English Electric Type 3 (British Rail Class 37)

- English Electric Type 4 (British Rail Class 40)

- English Electric Type 4 (British Rail Class 50)

- English Electric Type 5 (British Rail Class 55)

- British Rail Class 73, components assembled by BR.

- British Rail Class 83

- British Rail Class 86

- British Rail Class 487

- British Rail D0226

- Diesel Prototype 1 or Deltic led to the Class 55

- British Rail DP2 Class 55 body, re-engined with an E.E. 16csvt, led to the British Rail Class 50

- British Rail GT3 (gas turbine)

- CP Class 1400 (Portugal)

- CP Class 1800 (Portugal)

- JNR ED17 electric locomotive

- JNR EF50 electric locomotive

- Keretapi Tanah Melayu Class 15 shunter

- Keretapi Tanah Melayu Class 20

- Keretapi Tanah Melayu Class 22

- MRWA G class

- Nigerian Class 1001

- NIR 1 Class

- NS 500 Class

- NS 600 Class

- New Zealand DE class locomotive

- New Zealand Railways DF class (not to be confused with the DF class of 1979)

- New Zealand Railways DG class

- New Zealand Railways DI class

- DM/D class electric multiple units

- New Zealand Railways EC class

- NZR ED class (one, with components for a further nine supplied to New Zealand Railways)

- New Zealand E class locomotive (1922)

- New Zealand Railways EO class

- New Zealand Railways EW class

- PKP class EU06

- PKP class EN80 (Electric Multiple Unit)

- Queensland Railways 1200 class

- Queensland Railways 1250 class

- Queensland Railways 1270 class

- Queensland Railways 1300 class

- Queensland Railways 2350 class

- Queensland Railways 2370 class

- Rhodesia Railways class DE2

- Rhodesia Railways class DE3

- Tasmanian Government Railways X class

- Tasmanian Government Railways Y class (supplied parts local construction)

- Tasmanian Government Railways Z class

- Tasmanian Government Railways Za class

- Victorian Railways L class (electric)

- Victorian Railways F class

- Western Australian Government Railways C class

- Western Australian Government Railways H class

- Western Australian Government Railways K class

- Western Australian Government Railways R class

- Goldsworthy railway 1 class

- Goldsworthy railway 3 class

Several industrial diesel and electric locomotive types were also built for UK and export use.

References

- City Notes. The Times, Wednesday, 1 January 1919; pg. 13; Issue 41986

- English Electric and GEC plan biggest merger in Britain. The Times (London), Saturday, 7 September 1968; pg. 1; Issue 57350

- Payroll of 250,000 for the new giant. The Times (London), Saturday, 14 September 1968; pg. 13; Issue 57356

- City News in Brief, The Times, Friday, 11 March 1921; pg. 17; Issue 42666

- English Electric Company. The Times, Thursday, 22 April 1926; pg. 21; Issue 44252

- Prospectus, English Electric Company, Limited. The Times, Wednesday, 16 July 1919; pg. 18; Issue 42153

- City News in Brief. The Times, Saturday, 15 November 1919; pg. 19; Issue 42258

- The English Electric Company. The Times, Friday, 17 April 1931; pg. 21; Issue 45799

- English Electric Company, chairman's address to shareholders. The Times, Thursday, 31 March 1927; pg. 21; Issue 44544

- English Electric Company. The Times, Tuesday, 1 May 1928; pg. 25; Issue 44881

- English Electric Company. The Times, Saturday, 19 April 1930; pg. 16; Issue 45491

- English Electric Scheme. The Times, Tuesday, 4 February 1930; pg. 20; Issue 45428

- English Electric Directorate. The Times, Tuesday, 10 June 1930; pg. 18; Issue 45535

- English Electric. The Times, Thursday, 12 June 1930; pg. 20; Issue 45537.

- English Electric. The Times, Wednesday, 30 July 1930; pg. 18; Issue 45578

- English Electric Directorate. The Times, Friday, 26 September 1930; pg. 21; Issue 45628

- Geoffrey Tweedale, ‘Mensforth, Sir Holberry (1871–1951)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- English Electric Company. The Times, Friday, 4 March 1932; pg. 24; Issue 46073

- English Electric Company. The Times, Tuesday, 7 April 1936; pg. 23; Issue 47343.

- City News in Brief. The Times, Monday, 10 July 1933; pg. 21; Issue 46492

- Business Changes. The Times, Saturday, 2 January 1937; pg. 17; Issue 47572

- City Notes.The Times, Wednesday, 17 February 1937; pg. 20; Issue 47611

- City Notes. The Times, Thursday, 25 February 1937; pg. 19; Issue 47618

- City Notes. The Times, Thursday, 10 February 1938; pg. 19; Issue 47915

- The English Electric Company Limited. The Times, Tuesday, 9 August 1938; pg. 51; Issue 48068

- Air Defences. From Our Aeronautical Correspondent. The Times, Thursday, 2 February 1939; pg. 13; Issue 48219

- City Notes. The Times, Wednesday, 8 February 1939; pg. 20; Issue 48224

- English Electric Company. The Times, Wednesday, 22 February 1939; pg. 22; Issue 48236

- War achievements, English Electric Company. The Times, Friday, 2 March 1945; pg. 9; Issue 50081

- From Tramcars To Bombers. The Times, Monday, 9 April 1945; pg. 2; Issue 50112

- The offer of the English Electric Company. The Times, Tuesday, 29 December 1942; pg. 7; Issue 49429

- Company Meeting. The Times, Friday, 1 March 1946; pg. 10; Issue 50389

- "C.P. Snow facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about C.P. Snow". www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com.

- Three New British Aircraft. The Times, Thursday, 20 September 1945; pg. 2; Issue 50252

- Instruction manuals and advertising brochures for the Type UED and Type ZWA versions

- Oral history interview with Arthur L. C. Humphreys, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota.

- Flight 13 March 1924

- Chris Gibson Vulcan's Hammer p35

External links

- "English Electric Traction Ads", www.flikr.com, 29 January 2018, English Electric Traction advertisements and corporate brochures

- "English Electric Archive", englishelectric.zenfolio.com, English Electric locomotive images

- Clippings about English Electric in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW