English Gothic stained glass windows

English Gothic stained glass windows were an important feature of English Gothic architecture, which appeared between the late 12th and late 16th centuries. They evolved from narrow windows filled with a mosaic of deeply-coloured pieces of glass into gigantic windows that filled entire walls, with a full range of colours and more naturalistic figures. In later windows, the figures were often coloured with silver stain, enamel paints and flashed glass. Later windows used large areas of white glass, or grisaille, to bring more light into the interiors.

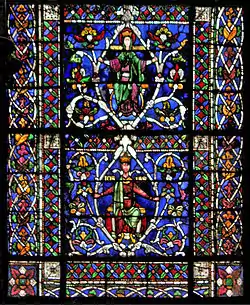

Detail of a Tree of Jesse Window from Canterbury Cathedral (late 12th–early 13th c.) | |

| Years active | 12th to 17th century |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

English Gothic windows followed roughly the same evolution of styles as English architecture: they followed windows in the Norman or Romanesque style, beginning in the late 12th century. somewhat later than in France. In the 13th century, the Decorated style appeared, which was divided into two periods: the later being the more ornate curvilinear. The next and last period was the Perpendicular Gothic, which lasted well into the 16th century, longer than in continental Europe.

Much of the original glass was destroyed in the English Reformation and has been replaced with modern work. However, examples of original glass are found in Canterbury Cathedral, Wells Cathedral, York Minster and Westminster Abbey.

Late 12th to end of 13th century: Early English Gothic

Characteristics

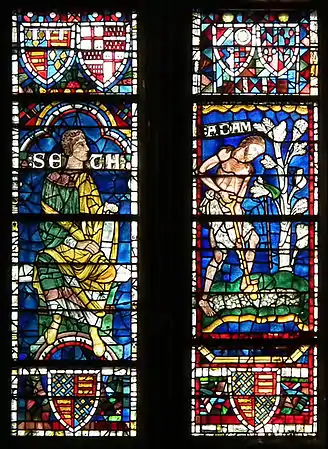

Seth and Adam Window, from Canterbury Cathedral (late 12th – early 13th c.)

Seth and Adam Window, from Canterbury Cathedral (late 12th – early 13th c.) Face from the Thomas Becket window at Canterbury Cathedral (late 12th – early 13th c.)

Face from the Thomas Becket window at Canterbury Cathedral (late 12th – early 13th c.) Reverse of the Thomas Becket window, showing leading and iron bars (late 12th-early 13th c.)

Reverse of the Thomas Becket window, showing leading and iron bars (late 12th-early 13th c.) Portion of a Tree of Jesse window, York Minster (late 12th – early 13th c.)

Portion of a Tree of Jesse window, York Minster (late 12th – early 13th c.)

The primary characteristics of early English glass are deep rich colours, particularly deep blues and ruby reds, often with a streaky and uneven colour, which adds to their appeal; their mosaic quality, being composed of an assembly of small pieces; the importance of the iron work, which becomes part of the design; and the simple and bold style of the painting of faces and details.[1]

All of the effects of the image are created by the colours of the pieces of glass. A single medallion at Canterbury Cathedral depicting Noah's Ark, no larger than a square foot (0.1m2), contains more than fifty pieces of glass, of blue, greenish-blue, green, and bits of white glass for the foam of the sea.[1]

A second important feature was the iron work. In early windows, before the introduction of stone tracery, the leaded panels of glass were inserted into an iron lattice or framework of upright and horizontal bars forming squares. The framework became a part of the design. In some cases, such as the upper windows, the figures were so large that they filled the whole window. In the lower windows, closer to the eye, each square space was filled with a single subject or image, usually framed by a circle. This was called a medallion window.[1]

The details of the early windows were added by painting in brown enamel, which was then fired onto the glass. Lettering and patterns were scratched out of the glass; there was no modelling of light and shade.[1]

In the later 13th century the windows gradually became more pictorial, more refined and mannerist, following the example of illuminated manuscripts. They took advantage of the delicate patterns of the tracery in the windows, added decorative illustrations in the margins, and often placed the central figures beneath elaborate arches and canopies.[2]

Grisaille windows became more popular in the 13th century because they allowed in more light. They were often decorated with floral motifs, such as cherry blossoms and ivy, in the borders. A famous set of these windows is found at Merton College, Oxford, from the end of the 13th or beginning of the 14th century. They portray the Apostles, and also the donor of the window, Henry de Maunsfeld, who appears in some twenty medallions.[2]

History

Thomas Becket window at Canterbury Cathedral (13th c.)

Thomas Becket window at Canterbury Cathedral (13th c.) Good Samaritan Window from Sens Cathedral (13th c.)

Good Samaritan Window from Sens Cathedral (13th c.).jpg.webp) The Five Sisters window at York Minster (13th c.)

The Five Sisters window at York Minster (13th c.).jpg.webp) Detail of diaper pattern of grisaille at York Minster (13th c.)

Detail of diaper pattern of grisaille at York Minster (13th c.).jpg.webp) Panel from York Minster depicting the legend of Saint Nicholas rescuing three children from being pickled (13th c.)

Panel from York Minster depicting the legend of Saint Nicholas rescuing three children from being pickled (13th c.).jpg.webp) Grisaille window at Merton College, Oxford (13th c.)

Grisaille window at Merton College, Oxford (13th c.)

The Gothic style in stained glass had first appeared in France in 1142, with the dedication of the stained glass windows in the ambulatory of the Basilica of Saint Denis. The earliest existing windows in the style in England are probably those at Canterbury Cathedral, including the Methuselah window in the choir clerestory. The choir of Canterbury was destroyed by a fire and was rebuilt by William of Sens, a French master-mason from Sens, introducing the French Gothic style to England.

The best-preserved is the east window in the part of the chapel called "Becket's Crown", in which only four or five of the twenty-four medallions are later copies. The Thomas Becket window features a decorative border in a repeat geometric pattern called a "mosaic diaper", which became a common feature of English windows in this period. Another novel feature of this window is a background of blue enamel painted on the glass, then scratched out to form a diaper pattern. This also became a common feature of later English windows.[3]

The Thomas Becket Window at Canterbury bears a striking resemblance to the Thomas Becket window in Sens Cathedral in France, where Becket spent his exile, and the home of William of Sens, the architect of the remodelling of Canterbury. The two windows were likely made by the same craftsmen.

During English Civil War in 1642–43, Puritan iconoclasts attacked the windows throughout the cathedral, climbing ladders and swinging pikes to smash the glass, which they considered to be idolatrous. However, four of the windows of Trinity Chapel still have most of their original glass, and the others were restored in the 19th century with imitations of the old glass. Another important 13th-century window is the "Five Sisters" window at York Minster (about 1260), notable especially for its large size and density of images. The popular name was given to the window by Charles Dickens.[2] Another collection of early windows is found in the Jerusalem Chamber of Westminster Abbey, built by Henry III of England, the brother-in-law of Louis IX of France, the creator of Sainte-Chapelle. Unfortunately, only a small number of original medallions remain.[2]

14th century: Decorated style

The 14th century saw a major change in the style and technique of English windows. It was brought about in part by changes in the architecture of English cathedrals and churches, and also by technical innovations, such as the use of silver stain to colour the glass.[4] It corresponded roughly with the English architectural style called Decorated, which in turn was divided into two periods: the earlier Geometric, in which tracery usually featured straight lines, cubes and circles; and the later Curvilinear whose tracery used gracefully curving lines.[5]

The later part of the 14th century, after about 1360, saw the arrival in England of Perpendicular Gothic. It brought a continual reduction in the amount of coloured space in the windows, and more and more grisaille. The number of lancets increased, and the number of small windows over the lancets grew, filling the wall space.[6]

Characteristics

.jpg.webp) Resurrection scene from Wells Cathedral (early 14th c.)

Resurrection scene from Wells Cathedral (early 14th c.) West window of York Minster, in curvilinear Decorated style, with a Flamboyant heart-shaped top (14th c.)

West window of York Minster, in curvilinear Decorated style, with a Flamboyant heart-shaped top (14th c.) The East window of Wells Cathedral (14th c.)

The East window of Wells Cathedral (14th c.) Deerhurst Priory, Gloucester, Saint Catherine (left) (beginning of 14th c.) and St. Alphege of Canterbury (right) (early 15th century)

Deerhurst Priory, Gloucester, Saint Catherine (left) (beginning of 14th c.) and St. Alphege of Canterbury (right) (early 15th century)

English cathedrals were expanded with greater numbers of small chapels, each of which required more light. This meant that windows could no longer be composed entirely of a mosaic of small circular medallions of deep, rich colours, as in the 12th and 13th centuries. Each bay had a group of tall, narrow lancet windows, usually topped by several small circular or clover-like windows. Each lancet, instead of having a multitude of small figures in medallions, had a single major figure in each section, usually a saint or apostle, in coloured glass, surrounded and set off by delicate patterns of white or lightly-tinted glass. The edges were often decorated with designs of flowers, ivy, and other plants, or geometric borders, and the tops and bottoms of the windows were decorated with birds, angels and grotesques. The glass at the top of the window was often also filled with painted architectural detail, such as arches, pinnacles and canopies, which harmonised with the architecture of the church itself. The figures in the windows showed the influence of medieval manuscripts; the poses were more natural.[4]

The 14th-century glass also showed technical improvement; thanks to the use of better quality sand and other ingredients, and improved techniques of heating and forming the glass, it was thinner, clearer, and more consistent in colour. It lost much of the smoky and streaked appearance which had given charm to the early Gothic glass.[4]

A major change in the 14th-century glass was a great reduction in the number of pieces of glass in a single window, which gave it a mosaic appearance. This was made possible by a technique called silver stain, which added a very thin coat of glass mixed with silver compounds, particularly silver nitrate, which was baked onto the outside of the window. Depending upon the formula used, this produced a light yellow, orange or green, which could be very bright, or, in flashed glass, could be scratched to produce more subtle tones and shading.[6]

The Perpendicular style in glass was characterised not just by vertical lines, but also by colour and the distribution of the glass. The blue and ruby backgrounds went up the entire height of each alternate section. The blue is lighter and greyer than in Decorated glass. White became more predominant, especially in figures, which were just touched with yellow stain.[7]

History

_Golden_window_crop.jpg.webp) The Tree of Jesse or "Golden Window" on the west of Wells Cathedral (1340–45), using silver stain for its golden colour

The Tree of Jesse or "Golden Window" on the west of Wells Cathedral (1340–45), using silver stain for its golden colour Detail of King Ine, Wells Cathedral (14th c.)

Detail of King Ine, Wells Cathedral (14th c.).jpg.webp) Detail of Lady Chapel windows, Wells Cathedral

Detail of Lady Chapel windows, Wells Cathedral

The first use of silver stain in England was at York Minster in about 1309,[6] and by the end of the century it was very widely used in English workshops, and gradually changed the nature of English windows. However, in English windows, the painting was often subtle. The most elaborate decoration was not in the painted glass, but in the tracery, in the stone mullions and iron bars that formed the framework for the window.[8] Examples included the west window of York Minster, whose glass was Decorated curvilinear, but whose tracery, especially at the top of the window, resembled that of the later French Flamboyant style. The curling form at the top gave the window the nickname "The Heart of Yorkshire".

Other important examples of the Decorated style are the Tree of Jesse Window, or "Golden Window", coloured with silver stain, in Wells Cathedral (c. 1345).[9][10] Others include the windows of the choir of the Chapel of Merton College at Oxford, donated by Henry de Mamesfeld. Oxford Cathedral and the Abbey Church of Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire contain early white windows painted with silver stain.[8]

Rose windows

The Dean's Eye, Lincoln Cathedral (completed 1235)

The Dean's Eye, Lincoln Cathedral (completed 1235).jpg.webp) Detail of the Dean's Eye Window

Detail of the Dean's Eye Window.jpg.webp) The Bishops's Eye, Lincoln Cathedral, in Decorated curvilinear style (completed 1330)

The Bishops's Eye, Lincoln Cathedral, in Decorated curvilinear style (completed 1330) Detail of the Bishops's Eye window

Detail of the Bishops's Eye window

Rose windows were rare in English Gothic cathedrals, but Lincoln Cathedral produced two fine examples: the Dean's Eye in the north transept and the Bishop's Eye in the south transept. The Dean's Eye was begun by the French-born Bishop, Saint Hugh of Lincoln, in the Early Gothic period in 1192, and was completed in 1235. The Bishops's Eye was not completed until a century later, in 1330, in the Decorated curvilinear style.

15th to early 16th century: Perpendicular and International Gothic

Characteristics

Great East Window, King's College Chapel, Cambridge

Great East Window, King's College Chapel, Cambridge.jpg.webp) Window of Merton College, Oxford, showing the dominance of white.

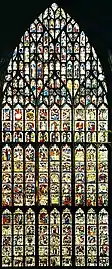

Window of Merton College, Oxford, showing the dominance of white. Perpendicular Great East window of York Minster

Perpendicular Great East window of York Minster Detail from the Great East Window, "Adam and Eve, the Fall from Grace" (1405-08)

Detail from the Great East Window, "Adam and Eve, the Fall from Grace" (1405-08)

Through the use of painting, silver stain and flashed glass, figures became more naturalistic, with shading and more details. The complex bays and vaults of Perpendicular architecture, with multiple decorative colonettes, ribs and openwork decoration spreading upwards and across the vaults, influenced the style. It encouraged the use of windows depicting hosts of angels in the upper windows. In the windows, heraldry and coats of arms of wealthy clients replaced portraits of the donors. The use of pale backgrounds continued, particularly panels of white delicately decorated with flowers, animals and coats of arms, which surrounded and set off the more colourful main figures.[11]

In the second half of the 15th century, the early tradition of surrounding figures with painted architectural features in the windows became less frequent, and figures began to appear against more varied backgrounds, such as landscapes.[11]

Improvements in the techniques of painting on the glass in vitreous enamel accelerated the tendency toward realism and a painterly style. The designs in the English windows became more intimate and anecdotal.[12]

During the late Gothic, the problem was sometimes not how to bring more light into the deeply coloured windows, but how to bring more colour into the pale white windows. Even the flesh of the figures was usually white. In a 15th century window, it was rare that more than one-fourth of the area was composed of coloured glass.[7] To add more colour, sometimes light colour was added to the background. Colourful figures occupied windows of the south transept window at York Minister, surrounded by delicately-coloured quarries, or panels, rather than a white background. Additional colour was brought in by adding touches of gold (made with silver stain) to the painted architectural canopies, pinnacles and crockets around and above the figures.[7]

The Perpendicular style called for figures that were longer, to fill the tall, narrow windows. In the windows of All Souls College, the figures occupied about one-half of the length of the window. The space above the figure was filled with painted architectural detail. The faces in Late Gothic were more finely drawn than in earlier styles, a development influenced by Flemish painting.[7]

History

Debut of Renaissance stained glass, from Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford (1516–1526)

Debut of Renaissance stained glass, from Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford (1516–1526) Renaissance window at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford by Abraham van Linge (17th century)

Renaissance window at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford by Abraham van Linge (17th century)

The International Gothic style, which appeared in the first half of the 15th century, was the final form of European Gothic, which borrowed from French, Dutch and German artists, and influenced the English style. German engraving and Flemish painting of the period had a particular influence on stained glass, not only in England but across Europe.[11]

The English perpendicular style was the other major influence.[11] New glass production was abundant, despite the War of the Roses. English glass craftsmen established important workshops in York, Norwich, and Oxford, which served clients in the surrounding regions. These clients included not only cathedrals and nobles, but also wealthy merchants and landowners who wanted impressive windows for their new residences.[11]

Glaziers developed personal styles, and their names became known. Examples were Thomas of Oxford, who made the windows of the Chapel of William of Wykeham's College at Winchester, and William of Conventry, the glazier of the Great East Window at York Minster (1405–1408). Another example was John Prudde, the King's glazier, who made the glass for Beauchamp Chapel of Saint Mary's at Warwick, which was commissioned in 1447.[12] Other important examples of the new style were the East window of the Priory of Great Malvern in Worcestershire (1423–39), and the windows of the chapel of All Souls' College at Oxford (1441–47).[12]

Another important influence was from Flemish painting. England developed close trade and political links with Flanders, and Flemish glaziers began to arrive in England, causing some disputes with the London Guild of Glaziers. Several important English works, such as windows at Fairfield Church in Gloucestershire and at King's College Chapel, Cambridge, were probably by Flemish artists, such as Dirk Vallet. By the early 17th century, the art of English Gothic windows was in its final decline. Some of the last windows, such as those by Abraham Van Linge at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, were simply like large paintings viewed through a grid of lead lines.[12]

The dividing line between Gothic stained glass art and Renaissance glass is traditionally placed at about 1530. The first important group of Renaissance windows in England was commissioned between 1516 and 1526 and installed at King's College Chapel, Cambridge.[13]

See also

Notes and citations

- Arnold 1913, Chapter III.

- Brisac 1994, p. 74.

- Arnold 1913, Chapter IV.

- Brisac 1994, p. 83.

- Smith 1922, pp. 45–47.

- Brisac 1994, p. 92.

- Day 1897, Chapter XVI - "Late Gothic Windows".

- Brisac 1994, p. 96.

- Swaan 1984, p. 193.

- "Wells Cathedral". The Medieval Stained Glass Photographic Archive. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Brisac 1994, p. 120.

- stained glass at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Day 1897, Chapter XVII - "Sixteenth Century Windows".

Bibliography

- Arnold, Hugh (1913). Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France. London: Adam and Charles Black. (Full text on Project Gutenberg)

- Brisac, Catherine (1994). Le Vitrail (in French). Paris: La Martinière. ISBN 2-73-242117-0.

- Day, Lewis (1897). Windows: a book about Stained and Painted Glass. London: B.T. Brastford. (Full text on Project Gutenberg)

- Ducher, Robert (1988). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-011539-1.

- Martindale, Andrew (1967). Gothic Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 2-87811-058-7.

- Smith, A. Freeman (1922). English Church Architecture of the Middle Ages - an Elementary Handbook. T. Fisher Unwin.

- Swaan, Wim (1984). The Gothic Cathedral. Omega. ISBN 978-0-907853-48-0.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.