Wales in the Late Middle Ages

Wales in the Late Middle Ages spanned the years 1282–1542, beginning with conquest and ending in union.[1] Those years covered the period involving the closure of Welsh medieval royal houses during the late 13th century, and Wales' final ruler of the House of Aberffraw, the Welsh Prince Llywelyn II,[2] also the era of the House of Plantagenet from England, specifically the male line descendants of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou as an ancestor of one of the Angevin kings of England who would go on to form the House of Tudor from England and Wales.[3]

| History of Wales |

|---|

|

|

|

The House of Tudor would go on to create new borders by incorporating Wales into the Kingdom of England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, effectively ever since then new shires had been created in place of castles, by changing the geographical borders of the Kingdoms of Wales to create a new definitions for towns and their surrounding lands.[4] Historians referring to the end of the late Middle Ages in Britain often reference the Battle of Bosworth Field involving Henry VII of England, which began a new era in Wales.[5]

History

End of the Aberffraw era

The senior family of the Kingdom of Gwynedd would descend from Owain Gwynedd and within a century the House of Aberffraw would come to acquire the title Prince of Aberfraw, Lord of Snowdon and would have 'de facto' suzerainty over the Lords in Wales. The titular princes did so in battle, and after the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn II), his brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd (Dafydd III / David) carried on resistance against the English for a few months, but was never able to control any large area. He was captured and executed by hanging, drawing and quartering at Shrewsbury in 1283. King Edward I of England now had complete control of Wales. The Statute of Rhuddlan was issued from Rhuddlan Castle in north Wales in 1284. The Statute divided parts of Wales into the counties of Anglesey, Merioneth and Caernarvon, created out of the remnants of Llewelyn's Gwynedd. It introduced the English common law system, and abolished Welsh law for criminal cases, though it remained in use for civil cases. It allowed the King of England to appoint royal officials such as sheriffs, coroners, and bailiffs to collect taxes and administer justice. In addition, the offices of justice and chamberlain were created to assist the sheriff. The Marcher Lords retained most of their independence, as they had prior to the conquest. Most of the Marcher Lords were by now Cambro Norman i.e. Norman Welsh through intermarriage.[2]

The Black Death

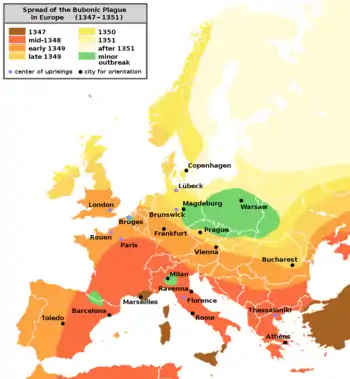

The Black Death arrived in Wales in late 1348. What records survive indicate that about 30 per cent of the population died, in line with the average mortality through most of Europe.

Welsh rebellion

The conquest of Wales did not end Welsh resistance, and a number of rebellions arose over the next century, between 1294 and 1409.

Madog ap Llywelyn

Madog ap Llywelyn led a Welsh revolt of 1294–95[6] and styled himself Prince of Wales.[7] In 1294, he put himself at the head of a national revolt in response to the actions of new royal administrators in north and west Wales.[8]

In December 1294 King Edward led an army into north Wales to quell the revolt. His campaign was timely, because several Welsh castles remained in serious danger. Edward himself was ambushed and retreated to Conwy Castle, losing his baggage train. The town of Conwy was burnt down and Edward besieged until he was relieved by his navy in 1295.[9]

The crucial battle occurred at the battle of Maes Moydog in Powys on 5 March 1295. The Welsh army successfully defended itself against an English cavalry charge. However, they suffered heavy losses, and many Welsh soldiers drowned trying to cross a swollen river.[10] Madog escaped but was captured by Ynyr Fychan of Nannau in Snowdonia in late July or early August 1295.[11]

Llywelyn Bren

Llywelyn Bren was a nobleman who led a 1316 revolt.[12] Following an order to appear before king Edward II of England, Llywelyn raised an army of Welsh Glamorgan men which laid siege Caerphilly Castle. The rebellion spread throughout the south Wales valleys and other castles were attacked, but this uprising only lasted a few weeks.[13] Hugh Despenser the Younger's execution of Llywelyn Bren helped to lead to the eventual overthrow of both Edward II and Hugh.[12][14]

Owain Lawgoch

In May 1372, in Paris, Owain Lawgoch announced that he intended to claim the throne of Wales. He set sail with money borrowed from Charles V,[15] but was in Guernsey when a message arrived from Charles ordering him to go to Castile to seek ships to attack La Rochelle.[16]

In 1377 there were reports that Owain was planning another expedition, this time with help from Castile. The alarmed English government sent a spy, the Scot John Lamb, to assassinate Owain.[16][17] Lamb stabbed Owain to death in July 1378.[15]

With the assassination of Owain Lawgoch the senior line of the House of Aberffraw became extinct.[16][18] As a result, the claim to the title 'Prince of Wales' fell to the other royal dynasties, of Deheubarth and Powys and heir Owain Glyndŵr.[15][18]

Glyndŵr Rising

The initial cause of Owain Glyndŵr's rebellion was likely the incursion of his land by Baron Grey of Ruthin and the late delivery of a letter requiring armed services of Glyndŵr by King Henry IV of England. Glyndŵr took the title of Prince of Wales on 16 September 1400 and proceeded to attack English towns with his armies in north-east Wales. In 1401 Glyndŵr's allies captured Conwy Castle and Glyndŵr was victorious against English forces in Pumlumon. King Henry led several attempted invasions of Wales but with limited success. Bad weather and the successful guerilla tactics of Glyndŵr raised his stature.[19]

In 1404, Glyndŵr captured Aberystwyth and Harlech castles. He was crowned Prince of Wales in Machynlleth and welcomed emissaries from Scotland, France, and Castille. French assistance arrived in 1405 and much of Wales was in Glyndŵr's control. In 1406 Glyndŵr wrote the Pennal Letter offering Welsh allegiance to the Avignon Pope and seeking recognition of the bishop of Saint David's as archbishop of Wales, and demands including that the "usurper" Henry Henry IV should be excommunicated. The French did not respond and the rebellion began to falter. Aberystwyth Castle was lost in 1408 and Harlech Castle in 1409 and Glyndŵr was forced to retreat to the Welsh mountains.[19] Glyndŵr was never captured, and the date of his death remains uncertain.[20]

The Tudors

In the Wars of the Roses over the English throne, which began in 1455, both sides made considerable use of Welsh troops. The main figures in Wales were the two Earls of Pembroke, the Yorkist Earl William Herbert and the Lancastrian Jasper Tudor. In 1485 Jasper's nephew, Henry Tudor, landed in Wales with a small force to launch his bid for the throne of England. Henry was partly of Welsh descent, born in Pembroke, raised in Raglan and his grandfather hailing from Anglesey. He counted princes such as Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys) among his ancestors, and his cause gained much support in Wales, relying on tales and prophecies of a native born Prince of Wales who would once again lead the Welsh people. Henry defeated King Richard III of England at the Battle of Bosworth, fighting under a banner of a red dragon and with an army containing many Welsh soldiers.[21]

On taking the throne as Henry VII of England, he broke with the convention that the Prince of Wales was named as the eldest son of the King, and declared himself Prince of Wales. During his reign he rewarded many of his Welsh supporters, and through a series of charters the principality and other areas saw the penal laws of Henry IV being abolished, although communities sometimes had to pay considerable sums for these charters.[22] There also remained some doubt about their legal validity.[23]

Laws in Wales Acts

Pressure from those within Wales and fears of a new rebellion led Henry VII's son, Henry VIII of England to introduce the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542, legally integrating Wales and England. The Welsh marches were shired and the Principailty and Marches were reunited into the single territory of Wales with a clearly defined border for the first time.[24][25] The Welsh legal system of Hywel Dda that had existed alongside the English system since the conquest by Edward I, was now fully replaced. The penal laws were obosoleted by acts that made the Welsh people citizens of the realm, and all the legal rights and privileges of the English were extended to the Welsh for the first time.[lower-alpha 1] These changes were widely welcomed by the Welsh people, although more controversial was the requirement that Welsh members elected to parliament must be able to speak English, and that English would be the language of the courts.[27]

Castles and Towns

After the Norman invasion of Wales, successive phases of castle construction in the British isles begun in the 11th century, then the 12th, but only in the 13th century did the Edwardian castle period begin in Wales. Dafydd III of Wales broke the Treaty of Aberconwy in place since 1277 to keep peace, and the manhunt begun the North Wales castle building phase with Conwy Castle, then Harlech and Caernarfon castles.[28][29] It was the likes of James of Saint George who hailed from Savoy, and brought European designed castles, St. George's official title was Master of the Royal Works in Wales (Latin: Magistro Jacobo de sancto Georgio, Magistro operacionum Regis in Wallia), and would work in Wales in Britain.[30] These Edwardian castles were either burnt to the ground in the Glyndŵr Rising in the 15th century, or, if they survived the Welsh rebellion, they were later slighted in the English Civil War. This was to prevent further military use e.g. Harlech castle was besieged successfully, but some still stand today as a testament to their construction. Caernarfon and Conwy castles have been incorporated into respective towns as examples of surviving castles.[31][32][33]

Edwardian castle era

King Edward I of England built a ring of impressive stone castles to consolidate his domination of Wales, and crowned his conquest by giving the title Prince of Wales to his son and heir in 1301.[34][35] Wales became, effectively, part of England, even though its people spoke a different language and had a different culture. English kings paid lip service to their responsibilities by appointing a Council of Wales, sometimes presided over by the heir to the throne. This Council normally sat in Ludlow, now in England but at that time still part of the disputed border area of the Welsh Marches. Welsh literature, particularly poetry, continued to flourish however, with the lesser nobility now taking over from the princes as the patrons of the poets and bards. Dafydd ap Gwilym who flourished in the middle of the fourteenth century is considered by many to be the greatest of the Welsh poets.[36]

Rhuddlan Castle built by master Mason St. George between 1280 and 1282 would be the name stakes for a new treaty which would incorporate all of Wales into one Principality in the Statute of Rhuddlan. The Treaty coincided with one of the last attacks of the Welsh on a Norman English built castle, Llywelyn II unsuccessfully attempting a revolt in 1282. The new government would include the ruling families of "Clares (Gloucester and Glamorgan), the Mortimers (Wigmore and Chirk), Lacy (Denbigh), Warenne (Bromfield and Yale), FitzAlan (Oswestry), Bohun (Brecon), Braose (Gower), and Valence (Pembroke)".[2][37] These families evolved from Welsh Marcher (Latin: Marchia Wallie) Lords who settled the borders and created a new Principality at the behest of King of England, these families descended from the Norman conquest and had by then integrated locally slower than their English compatriots.[38]

Castles were governed by Constables (Latin: ex officio), these men would be present like modern day police in each castle which was the centre of their respective towns. The constable lists of castles would vary but mostly were manned up until at least the Glyndwr rebellion, or thereabouts for over 150 years in the example of Flint Castle.[39] Flint castle in particular has held out over the ages in terms of its fame and notoriety, with thanks to William Shakespeare who wrote Richard II (play) and detailed the life and imprisonment of Richard II of England in the castle.[40] While Flint castle was slighted in the 17th century, the castle in the town of Conwy has enjoyed a relative longevity as a town centre, with 43 constables between 1284 – 1848. Flint along with most Welsh and English Edwardian castles were slighted or demolished eventually by the English civil war in the 17th century.[33][41]

Welsh and castles

.jpg.webp)

Many castles in Wales are ruins today, an example is Criccieth Castle, built by Llywelyn the Great. The castle was garrisoned by an English army until the Owain Glyndwr rebelled in 1404 and the town became occupied again by the Welsh after the Glyndwr Rising.[42] Another example of a castle built by the Welsh people is Powis Castle; the once residence is a rare instance of a complete castle still in use today. It was built by Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, who was a member of the Royal Kingdom of Powys and ordered its construction in the 13th century, the castle and lands were leased by the Herbert family during 1578. Of late the castle has become the property of the Welsh National trust, it's final private owner was George Herbert, 4th Earl of Powis until 1952.[43] Chirk Castle is another example of a Welsh fortress which has stood the test of time and is also under the protection of the national Trust.[44]

With Wales being cluttered with castles, it was during the Edwardian phase that most of the castles were erected after the Norman conquest.[45] However, during the reign of the Principality very few castles were built, Raglan Castle being a 15th-century example. Raglan was built by Sir William ap Thomas, the ‘blue knight of Gwent' a Welshman who started a new dynasty via his son William Herbert, 1st Earl who gained ownership of the castle. As well as Raglan, the Herbert family gained Chepstow from the English Earl of Norfolk. In 1508, Raglan castle passed to an English gentry family, Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester would become the first to use the Raglan estate as a private residence, this marked a new era of Welsh castle ownership and from then the usage of a public land surrounding castles became privatised.[4][46] As well as Raglan being privately owned by Welsh gentry, Carew Castle was gained by Rhys ap Thomas who mortgaged the estate and also too used the castle as a private residence.[47]

Notes

- By making the Welsh citizens of the realm it gave them equality under the law with English subjects," and speaking of the Welsh people, "At last they had had their wish and been granted by statute the full 'freedoms, liberties, rights, privileges and laws' of the realm. By conferring upon them legal authorization to become members of parliament, sheriffs, justices of the peace, and the like, the Act had done little more than give statutory confirmation of rights they had already acquired de facto. Yet, in formally handing power to members of the gentry, the Crown had conferred self-government upon Wales in the sixteenth-century sense of the term."[26]

References

- Ferguson 1962.

- Pierce, 1959a, p. 20.

- Wagner 2001, p. 206.

- Turner & Johnson 2006.

- Saul 2005.

- Moore 2005, p. 159.

- Pierce, 1959b.

- Griffiths 1955, p. 13.

- Griffiths 1955, p. 17.

- Jones 2008, p. 166.

- Jones 2008, p. 189.

- Jones 2007.

- Pierce, 1959a.

- Moore 2005, pp. 164–166.

- Walker 1990, pp. 165–167.

- Carr 1995, pp. 103–106.

- Pierce, 1959c.

- Davies 2000, p. 436.

- Davies 1995.

- Williams 1993, p. 5.

- Williams 1987, pp. 217–226.

- Johnes 2019, pp. 63, 64.

- Carr 2017, p. 268.

- Davies 1995, p. 232.

- Legislation.gov.uk.

- Williams 1993, p. 274.

- Williams 1993, pp. 268–73.

- Taylor 1997, p. 9.

- Stephen 1888.

- Morris 1901, p. 145.

- Stephen 1890.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 10, 13, 19.

- Ashbee 2007, p. 16.

- Davies 1987, p. 386.

- Stephen 1889.

- "DAFYDD ap GWILYM (fl. 1340-1370), poet". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Edwards 1906, pp. 58–59.

- Davies 2000, p. 271-288.

- Rickard 2002, p. 198.

- Kantorowicz 1957, pp. 24–31.

- Lowe 1912, pp. 187–328.

- "Criccieth Castle". cadw.gov.wales.

- "Powis Castle and Garden". nationaltrust.org.uk.

- "Chirk castle". nationaltrust.org.uk.

- "Is Wales the castle capital of the world?". cadw.gov.wales.

- Griffiths 2004.

- Pierce, 1959e.

Bibliography

- Ashbee, Jeremy (2007). Conwy Castle. Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-259-3.

- Barrow, G. W. S. (1956). Feudal Britain: the completion of the medieval kingdoms, 1066–1314. E. Arnold. ISBN 9787240008980.

- "BBC Wales - History - Themes - Welsh language: The Norman conquest". www.bbc.co.uk. 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Bremner, Ian (2011). "BBC - History - British History in depth: Wales: English Conquest of Wales c.1200 - 1415". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Carpenter, David (2015). "Magna Carta: Wales, Scotland and Ireland". Hansard.

- Carr, Anthony D. (1995). Medieval Wales. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0312125097.

- Carr, Anthony D (2017). The Gentry of North Wales in the later Middle Ages. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78683-136-1.

- "Crug Mawr, site of battle, near Cardigan (402323)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- Davies, John (1993). A History of Wales. Penguin Group. ISBN 0-14-028475-3.

- Davies, John (2020). Accident or Assassination?The Death of Llywelyn 11th December 1282 (PDF). Abbey Cwmhir Heritage Trust.

- Davies, Rees R. (1987). Conquest, Coexistence, and Change: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821732-9.

- Davies, R. R. (1995). The revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198205081.

- Davies, Rees R. (2000). The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820878-2.

- Davies, Rees R. (2013). Owain Glyndwr - Prince of Wales. Y Lolfa. ISBN 978-1-84771-763-4.

- Griffiths, John (1955). "The Revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn, 1294–5". Transactions of the Caernarfonshire Historical Society. 16: 12–24.

- (Griffiths, R.A. (2004). "Herbert, William, first earl of Pembroke (c. 1423–1469)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13053. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Edwards, Owen Morgan (1906). "Chapter 12". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 58-59.

- Ferguson, Wallace K. (1962). Europe in transition, 1300-1520.

- Jenkins, Geraint (2007). A Concise History of Wales. pp. 118–119.

There were to be no further major uprisings of this kind against the power of the Crown.

- Jones, Craig Owen (2007). Compact History of Welsh Heroes: Llywelyn Bren. Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 978-1845270988.

- Johnes, Martin (2019-08-25). Wales: England's Colony?. Parthian Books. ISBN 978-1-912681-56-3.

- Jones, Craig Owen (2008). Compact History of Welsh Heroes: The Revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn. Gwalch.

- Jones, Francis (1969). The Princes and Principality of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780900768200.

- Jones, Thomas (1947). Gerallt Gymro. Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Kantorowicz, H. Ernst (1957). The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 24–31.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911). A History of Wales, from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. Vol. II (2 ed.). Longmans, Green & Co. ISBN 978-1-334-06136-3.

- "Laws in Wales Act 1535 (repealed 21.12.1993)".

- Long, Tony (2007). "Oct. 3, 1283: As Bad Deaths Go, It's Hard to Top This". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- Lowe, Walter Bezant (1912). The Heart of Northern Wales: As it was and as it Is, Being an Account of the Pre-historical and Historical Remains of Aberconway and the Neighbourhood. W.B. Lowe.

- Maund, Kari L. (2006). The Welsh Kings: Warriors, Warlords, and Princes (3rd ed.). Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2973-1.

- Moore, David (2005). The Welsh Wars of Independence circa 410-1415. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-3321-9.

- Moore, David (10 January 2007). The Welsh Wars of Independence. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9648-1. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Morris, John E. (1901). The Welsh Wars of Edward I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 145.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "Llywelyn ap Gruffydd or Llywelyn Bren (died 1317) nobleman, soldier and rebel martyr". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "MADOG ap LLYWELYN, rebel of 1294". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "OWAIN ap THOMAS ap RHODRI (' Owain Lawgoch '; died 1378), a soldier of fortune and pretender to the principality of Wales". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "Llywelyn ap Iorwerth ('Llywelyn the Great', often styled 'Llywelyn I', prince of Gwynedd)". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "RHYS ap THOMAS, Sir (1449 - 1525), the chief Welsh supporter of Henry VII". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Pilkington, Colin (2002). Devolution in Britain today. Manchester University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-7190-6075-5.

- Powicke, F. M. (1962). The Thirteenth Century: 1216–1307 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-82-1708-4.

- Prestwich, Michael (2007). Plantagenet England: 1225–1360 (new ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822844-8.

- Rickard, John (2002). The Castle Community: The Personnel of English and Welsh Castles, 1272-1422. p. 198. ISBN 0851159133.

- Saul, Nigel (1 March 2005). A Companion to Medieval England (2nd ed.). The History Press LTD. ISBN 978-0-7524-2969-4.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1888). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 14. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 204.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1889). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 17. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 14–38.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1890). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 21. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 427–434.

- Stephenson, David (1984). The Governance of Gwynedd. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-0850-9. OL 22379507M.

- Taylor, Arnold (1997) [1953]. Caernarfon Castle and Town Walls (4th ed.). Cardiff: Cadw – Welsh Historic Monuments. p. 9. ISBN 1-85760-042-8.

- "Transcript - The National Archives - Exhibitions - Uniting the Kingdoms?". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Turner, Rick; Johnson, Andy (2006). Chepstow Castle – its history and buildings. ISBN 1-904396-52-6.

- Wagner, John (2001). Encyclopedia of the Wars of the Roses. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-358-3.

- Walker, David (1990). Medieval Wales. Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-521-31153-3.

- Williams, Glanmor (1987). Recovery, reorientation and reformation: Wales c.1415-1642. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821733-1.

University of Wales Press

- Williams, Glanmor (1993). Renewal and Reformation: Wales C. 1415-1642. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285277-9.

- Williams, Gwyn A. (1985). When was Wales?: a history of the Welsh. Black Raven Press. ISBN 0-85159-003-9.