Eotriceratops

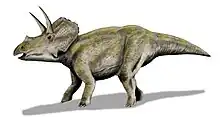

Eotriceratops (meaning "dawn three-horned face") is a genus of herbivorous ceratopsian dinosaurs which lived in the area of North America during the late Cretaceous period. The only named species is Eotriceratops xerinsularis.

| Eotriceratops Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Chasmosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Triceratopsini |

| Genus: | †Eotriceratops Wu et al., 2007 |

| Species: | †E. xerinsularis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Eotriceratops xerinsularis Wu et al., 2007 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Discovery and naming

In early August 1910, Barnum Brown during an American Museum of Natural History expedition discovered a large dinosaur skeleton in the Dry Island site, on the west bank of the Red Deer River in southern Alberta, Canada. Brown, however, neglected this discovery as he was more interested in the many Albertosaurus specimens present in the area. Unaware of Brown's find, in 2001 a team of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology and the Canadian Museum of Nature mounted an expedition to the Dry Island. The expedition's cook, Glen Guthrie, rediscovered the skeleton by accident.[1]

Eotriceratops was named and described by Xiao-Chun Wu, Donald B. Brinkman, David A. Eberth and Dennis R. Braman in 2007. The type species is Eotriceratops xerinsularis. The generic name combines a Greek ἠώς, èos, "dawn", with the name of the genus Triceratops, in reference to an older age relative to that form. The specific name xerinsularis, means "of the dry island", from Greek ξηρός, xèros, "dry", and Latin insula, "island" and is a reference to the Dry Island Buffalo Jump Provincial Park where its remains were found.[1]

The holotype specimen, RTMP 2002.57.5, was found in a layer of the uppermost Horseshoe Canyon Formation, dated to the early Maastrichtian, about 68.8 million years ago.[2] It consists of a partial skeleton with much of the skull; the skull lacks the lower jaws. but includes parts of the edges of the frill, large horns above the eyes, and a small horn above the nose, similar to the closely related Triceratops. At least seven neck and five back vertebrae, as well as several ribs and ossified tendons, were also recovered. The bones were largely found disarticulated. Because the specimen was found in weakly bedded shale, many of the bones were badly crushed.[1]

In 2010, Gregory S. Paul renamed the species Triceratops xerinsularis,[3] but this inclusion of Eotriceratops in the existing genus Triceratops has not been followed by other researchers.

Possible additional specimens, which have been variously included in the species Ojoceratops fowleri and Torosaurus utahensis, are known from the same time period in New Mexico and may also belong to Eotriceratops.[4]

Description

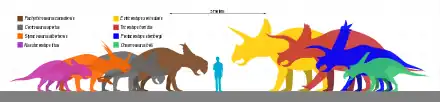

The holotype skull has been estimated to have had an original length of around 3 m (9.8 ft).[1] It would have been a large animal, measuring 8.5–9 metres (28–30 ft) in length and 10 metric tons (11 short tons) in body mass.[3][5]

Eotriceratops differs from other chasmosaurine ceratopsians in unique features of the skull bones. In 2007, several autapomorphies, unique derived traits, were established. The process of the praemaxilla, obliquely protruding to above and behind in the bony nostril, does not have a groove or depression on its outer side contrary to the situation with Triceratops; this process is exceptionally wide in side view; it also reaches above the level of the lower border of the fenestra interpraemaxillaris. The episquamosals, the epoccipitals of the squamosal, thus the skin ossifications lining and often protruding from the edge of the frill, have an extremely elongated base, and are flattened and spindly, touching each other as with Torosaurus utahensis. Near the lower edge of the squamosal a clearly demarcated groove or depression is present. On the lower front of the nasal horn core, a vertical, slightly obliquely running, vein groove meets second vein groove, running horizontally. The epijugal forms an unusually pronounced sharp jugal horn. At its rear upper side the epijugal bears a pronounced process, pointing to behind. A depression on the top of the epijugal forms a contact facet with the jugal; a depression at its inner side forms a separate facet contacting the quadratojugal.[1]

The snout of Eotriceratops was relatively flat and elongated. The depressions on the sides of the praemaxillae were connected through an oval fenestra interpraemaxillaris; small rounded processes pointed to above and behind into this opening, originating from the front lower edges. The strut between this opening and the nostril was narrow in side view and transversely thickened with a straight rear edge. The processes jutting into the nostrils had hollow outer sides but were far less excavated and much higher than with Triceratops or Torosaurus. The maxilla bore at least thirty-five tooth positions. The nasal horn was low, situated above the nostril and slightly recurved. It had a narrow rear edge and a transversely flattened point. The horns above the eyes were forward-curving and have been estimated at about 80 cm (2.6 ft) long. The lower base of these horns was narrow and vertically directed, which with Triceratops is a juvenile trait. Three bite marks can be observed above the eye, near the base of the left horn, which were interpreted as traces of scavenging. The squamosal shows at least five episquamosals. Little has been preserved of the parietal bones forming the centre of the neck shield.[1]

Phylogeny

Eotriceratops was in 2007 placed in the Chasmosaurinae. In a cladistic analysis, it was recovered as a close relative of Triceratops, Nedoceratops and Torosaurus. It would have been the sister species of Triceratops. In view of its greater age, the describing authors considered it more likely that Eotriceratops was in fact basal to, lower in the evolutionary tree than, the other three genera.[1]

See also

References

- Wu, X-C.; Brinkman, D.B.; Eberth, D.A.; Braman, D.R. (2007). "A new ceratopsid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the uppermost Horseshoe Canyon Formation (upper Maastrichtian), Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 44 (9): 1243–1265. Bibcode:2007CaJES..44.1243W. doi:10.1139/E07-011.

- Eberth, D.A.; Kamo, S.L. (2019). "High-precision U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS dating and chronostratigraphy of the dinosaur-rich Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Upper Cretaceous, Campanian–Maastrichtian), Red Deer River valley, Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 57 (10): 1220–1237. doi:10.1139/cjes-2019-0019. S2CID 210299227.

- Paul, G. S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. pp. 265. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- Wick, S. L.; Lehman, T. M. (2013). "A new ceratopsian dinosaur from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of West Texas and implications for chasmosaurine phylogeny". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (7): 667–82. Bibcode:2013NW....100..667W. doi:10.1007/s00114-013-1063-0. PMID 23728202. S2CID 16048008.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages (PDF).

Winter 2011 Appendix

.png.webp)