Epidemics Act

Epidemics Act (EpidA) is a federal act of the Swiss Confederation, which aims to protect humans from infections and to prevent and control the outbreak and spread of communicable diseases. The epidemic act currently in force is the result of the total revision of September 28, 2012. The revision had become necessary because the environment in which infectious diseases occur and pose a threat to public health has changed and the act had to be adapted to the conditions.

| Epidemics Act (EpidA) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Federal Assembly of Switzerland | |

| |

| Territorial extent | Switzerland |

| Enacted by | Federal Assembly of Switzerland |

| Enacted | 28 September 2012 |

| Commenced | 1 January 2016 |

| Repeals | |

| Epidemics Act (1970) | |

| Status: Current legislation | |

An optional referendum against this total revision was initiated by the EDU, the Verein Bürger für Bürger and the committee Wahre Demokratie, and the quorum of 50,000 signatures was reached within 100 days. As a result, a referendum was held on September 22, 2013, in which the people approved the total revision with 60% votes in favor.

Development of the Epidemics Act

The Federal Act of 28 September 2012 on Controlling Communicable Diseases of Human Beings, which is currently in force, represents a total revision of the Federal Act of 18 December 1970. This in turn originated from the Federal Law of July 2, 1886, concerning measures against epidemics dangerous to the public. The Epidemics Act of 1886 dealt only with smallpox, cholera, typhus and plague, so-called "public health epidemics". The rest was a matter for the cantons. The outbreak of a typhus epidemic in Zermatt in 1963, with about 400 cases and several deaths, led to a total revision of the Epidemics Act of 1886. The emergence of other diseases, such as tuberculosis, had already led to an amendment of the Swiss Federal Constitution. Between the total revision of December 18, 1970, and that of September 28, 2012, there were several minor legislative revisions (the last in 2006), more or less all of which had the effect of significantly expanding the powers of the federal government.[1]

Purpose of the Act

The purpose of the revised Epidemics Act is the rapid and unbureaucratic coordination of all infrastructures that can contribute to the goal of surveillance, prevention and control of communicable diseases in humans. Three levels can be declared by the federal government with immediate effect according to the EpidA: the normal situation, the special situation and the extraordinary situation.

During the normal situation, the cantons are in charge of enforcing the Epidemics Act and the Epidemics Ordinance (EpV). The Confederation has very few competences, which are limited to information and recommendations, control of entry and exit, and coordination - if requested by the cantons.

In a special situation (Art. 6 EpidA), the Federal Council may order quarantine for individuals, impose capacity restrictions on events or even cancel them; it is empowered to close schools; physicians and other health professionals may be required to cooperate in combating the disease that is rampant at the time; and it may declare vaccinations mandatory. These regulations may take the form of a specific injunction (for example, banning a specific event) or an ordinance (for example, banning events throughout Switzerland). The special situation is defined as an epidemiological emergency and can be compared to a moderate influenza pandemic, the SARS pandemic and H1N1. During the special situation, the FDHA coordinates federal measures. The special situation exists when "ordinary law enforcement agencies are unable to prevent and control the outbreak and spread of communicable diseases and one of the following hazards exists". (Art. 6 para. 1 let. an EpidA). In addition, one of the following conditions must also be met:

- increased risk of spreading and contagion,

- particular risk to public health,

- risk of serious impact on the economy or on other areas of life

In an exceptional situation (Art. 7 EpidA), the Federal Council may, on the basis of Art. 185 para. 3 of the Swiss Federal Constitution, issue emergency decree that have no basis in a federal act passed by Parliament and subject to an optional referendum by the people. Because the Federal Council is already constitutionally empowered to issue these ordinances, Art. 7 EpidA is declaratory in nature. Due to the unpredictability of an acute, serious threat to public health, no specific measures are provided for the extraordinary situation. In the event of an occurrence, constitutional emergency law allows the Federal Council to order adequate measures. According to Art. 7d of the Government and Administration Organization Act (RVOG), these ordinances shall cease to have effect if the Federal Council does not submit to Parliament, within six months at the latest, a draft federal law or parliamentary emergency ordinance replacing those of the Federal Council. For an extraordinary situation to arise, a national threat situation that threatens the external or internal security of Switzerland is required. Only so-called worst-case pandemics, such as the Spanish flu or the Covid 19 pandemic, are eligible for this.[2]

Content

Detection and monitoring

Art. 11 EpidA grants the FOPH the competence to set up and operate systems for the early detection and monitoring of potential hazardous situations. This is done in close cooperation between the FOPH and the cantons, but also the BLV or the FOEN. This close cooperation between the FOPH, other federal agencies and the cantons is of great importance. The cantons contribute their proximity to epidemiological events and health-related incidents as well as their responsibility for enforcement, while the FOPH ensures uniform reporting and assessment criteria, professional epidemiological data processing and international networking. The involvement of other federal agencies enables a uniform assessment of the situation and thus uniform enforcement. The central instrument here is the obligation to report under Art. 12 EpidA. It obliges the medical profession, hospitals, but also rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, outpatient clinics, organizations or telephone medical advice services and pharmacies to report communicable diseases to the FOPH or the competent cantonal authority. Those diseases that are associated with an epidemic risk or a severe course of disease are monitored. This also applies to events that are novel or unexpected or for which surveillance is internationally agreed.

The obligation to report is listed in Art. 12 EpidA. The diagnosing physicians must report observations of communicable diseases to the cantonal medical services, which in turn forward these reports to the FOPH. In principle, the reports are first sent to the authority responsible for immediate measures. In certain cases, in particular when emergency measures involving more than one canton and international notification are required, notifications should also be made directly to the FOPH. In addition, the Federal Council may order that prevention and control measures and their effects be reported and that samples and test results be sent to the laboratories designated by the competent authorities.

Vaccines

The FOPH and the Federal Commission for Vaccination Issues regulate the strategies and objectives relating to vaccinations. To implement these, both bodies issue specific vaccination recommendations (Art. 20 EpidA). Art. 20 paragraph 2 states: "Physicians and other health professionals shall contribute to the implementation of the national vaccination plan within the scope of their activities". According to Art. 22 EpidA, the cantons may "declare vaccinations of vulnerable population groups, of particularly exposed persons and of persons performing certain activities to be compulsory if there is a significant risk". During a special and exceptional situation, the Federal Council may also order compulsory vaccination. A so-called mandatory vaccination (Swiss for compulsory vaccination) can thus only be imposed for vulnerable groups and not generally for the entire population. Furthermore, this measure is reserved for those situations where all means have been exhausted. This is because compulsory vaccination constitutes an interference with personal freedom (Art. 10 para. 2 Federal Constitution [FC]). According to Art. 36 FC, such restrictions of fundamental rights are only permissible if (1) they are based on a sufficient legal foundation, (2) they are justified by a public interest (in the case of highly contagious diseases with a potentially very severe course), and (3) they are proportionate. Mandatory vaccination of certain groups of people may be warranted in the case of a serious, rapidly spreading, and in many cases fatal infectious disease.

Compensation and pain and suffering for vaccine adverse event regulated in Art. 64 ff. EpidA.

Biological safety

The Epidemics Act requires compliance with a executive care by persons handling pathogens or their toxic products. It stipulates that all measures must be taken to ensure that no harm to humans results from this activity (Art. 25 EpidA). This duty of care on the part of the user also covers the handling of genetic material or microorganisms that could cause disease as a result of genetic modification. Art. 28 EpidA goes on to state: "Anyone who places pathogens on the market must inform purchasers about the properties and hazards relevant to health and about the necessary precautionary and protective measures". The Federal Council is also authorized to restrict or ban the handling of certain pathogens. Also in the context of the WHO action plan to eradicate poliomyelitis, the destruction of polio-infectious materials or a ban and/or restriction on the handling of polioviruses in closed systems may be necessary in the long term. Moreover, the competence of the Federal Council in the field of bioweapons is in the context of Switzerland's obligations under international law (see Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction).

Combat

More or less all measures to protect public health affect the constitutionally guaranteed rights of freedom. Therefore, the competent authorities have to take responsibility. They also have to make decisions where an adequate scientific assessment is difficult. Because all dangers cannot be defined conclusively, the competent authorities have a wide margin of discretion as to how they wish to take measures. In accordance with the principle of proportionality, these measures are only lawful if all less restrictive ones have been exhausted.

Based on the varying intensity of the measures, the Federal Council describes a sequence of stages provided for by the law. The mildest measure is medical surveillance (Art. 34 EpidA). The ban on practicing a profession or activity (Art. 38 EpidA) would have a stronger intrusive effect. Seclusion in a hospital or in another suitable institution (Art. 35 EpidA) is the most severe measure, along with an order for medical treatment (Art. 37 EpidA). The law distinguishes between isolation and quarantine. The former refers to the isolation of the sick and infected, while quarantine refers to the isolation of those suspected of being infected or infected. The aim of both measures is to interrupt chains of infection. Both measures must be ordered in advance in the domicile of the person concerned. Placement in another institution is only permissible if placement at home is insufficient or impossible to effectively prevent the further spread of the disease.

The Epidemics Act provides the cantonal authorities with a wide range of instruments with which they can prevent the spread of communicable diseases. For example, Art. 40 provides that events may be banned or restricted, schools and other public institutions may be closed? the entering and leaving of certain buildings and areas, as well as certain activities in defined locations, may be prohibited. According to Art. 41, para. 2, the FOPH is empowered to require persons entering or leaving Switzerland:

- provide their identity, itinerary and contact information;

- provide a vaccination or prophylaxis certificate;

- provide information about their state of health;

- provide proof of a medical examination;

- to undergo a medical examination.

To prevent the spread of a disease, the FOPH may refuse to allow individuals to leave the country. However, this measure is to be used as Ultima ratio.

Organization and procedure

The Epidemics Act provides for two bodies: the emergency response body and the coordination body. The emergency body exists only temporarily and can be called out in the event of special and extraordinary situations (Art. 55 EpidA). If this happens, any special task force (Art. 4 IPV) that has been deployed in the course of the epidemiological (emergency) situation is dissolved and transferred to the operational body. The tasks of the operational body are to advise the Federal Council and to assist in the coordination of measures. Since the total revision of 28 September 2012, there has been a coordination body (KOr EpidA), which has its legal basis in Art. 54 EpidA. Its task is to coordinate cooperation between the federal government and the cantons at the technical level, but it has no decision-making or enforcement powers; this is the responsibility of the federal government and the cantons. The coordination body may form sub-bodies as needed; one is provided for the area of zoonoses. These sub-bodies are to be staffed in particular with members of the FOPH and the cantonal medical profession. In the coordination body, the Confederation is in charge; however, it is not an extra-parliamentary commission within the meaning of Art. 57a RVOG.

The law also provides for the Federal Commission for Vaccination Matters (Art. 56 EpidA) and the Federal Expert Commission for Biosafety (Art. 57 EpidA). The former is responsible for advising the Federal Council on the enactment of regulations and the federal and cantonal authorities on enforcement. The Federal Expert Commission for Biosafety advises the authorities on the protection of humans and the environment in the field of biotechnology and gene technology.

Completion

Enforcement of the Epidemics Act is the responsibility of the cantons, unless the Confederation is responsible (Art. 75 EpidA). This is also derived from the Federal Constitution, which provides in Art. 118 para. 2 that the Confederation is only operationally active in specific areas of health protection. Nevertheless, legislation on communicable diseases is the sole responsibility of the Confederation, which also ensures that federal law is observed by the cantons (Art. 186 para. 4 FC). According to Art. 77 para. 2, the Confederation coordinates the enforcement measures of the cantons insofar as there is an interest in uniform enforcement. To this end, it may, for example, prescribe measures for uniform enforcement to the cantons or compel them to implement certain measures should a threat to public health be indicated."[3]

Total revision of the Epidemics Act of September 28, 2012.

Initial situation

In its message, the Federal Council was of the opinion that the previously applicable Epidemics Act no longer met the requirements. Since the enactment of the Epidemics Act in 1970, so much had changed that a total revision was indispensable - both from a legal and a technical point of view. In his opinion, the legal situation was too vague to adequately prepare for the outbreak and spread of a disease. Too often, one had to rely on emergency articles (Art. 10 aEpidA[4]), the scope of which, however, was again vaguely defined, as the SARS pandemic had shown. Likewise, the current law had been limited to sanitary measures and had largely left out preventive measures. Finally, a so-called purpose article was missing, from which it was clear which public interests were served by the legal instructions. This is important because all actions of the state must serve the public interest. The lack of an article of purpose had limited the spectrum of possible legal actions, since the measures could not be based on a legal purpose.

Procedure

The need for a revision of the Epidemics Act was undisputed during the negotiations. In the National Council, only the question of the vaccination obligation proposed by the Federal Council was controversial. For the opponents, compulsory vaccination was out of the question because it would represent too far-reaching an encroachment on personal freedom. The effectiveness and side effects of new vaccines could often only be proven after years. Proponents, on the other hand, argued that in the event of an extraordinary situation, public health must be given greater weight than individual freedom. Moreover, it is a vaccination policy; no one is vaccinated by force against their will. Those who do not comply with the vaccination obligation, however, may have to reckon with measures under labour law. A motion by opponents aimed at relativizing the vaccination obligation was rejected by 94 votes to 69 and 105 votes to 51. On the other hand, another proposal from the SP and the SVP was accepted by 103 votes to 62. According to this proposal, the cantons would no longer be allowed to order vaccinations, but only to propose and recommend them.

In the Council of States, the competence of the cantons to declare vaccinations mandatory for certain groups of people under certain circumstances was approved by seven votes to eleven. As this decision was contrary to the decision of the National Council, a difference vote took place, in which the National Council bowed to the decision of the Council of States and thus accepted (by 88 votes to 78) that cantons may declare vaccinations mandatory.

In the final votes, the new federal law was approved in the National Council by 149 votes to 14 with 25 abstentions and in the Council of States by 40 votes to two with three abstentions.[5]

Changes to the previous law

Compared to the 1970 law, some aspects have changed in the course of the total revision:

- a tiered model of normal, special and extraordinary situation was newly introduced to improve the division of labor between the Confederation and the cantons in crisis situations;

- a vaccination obligation may no longer be imposed generally, but only for designated persons. The Federal Council may now also impose a vaccination obligation during a special or extraordinary situation, but the same criteria apply as for the cantons;

- explicit legal provisions have been created to improve crisis prevention and management;

- likewise, the leadership role of the Confederation was expanded in the new law. For example, it is responsible for defining national goals and strategies in the fight against communicable diseases and for the overall supervision of the enforcement of the Epidemics Act;

- and the Coordinating Body (KOr EpidA) was newly created.[6]

Optional referendum

On September 28, 2012, the Federal Assembly passed the resolution to adopt the revised law. After publication by the Federal Chancellery in the Federal Gazette, the referendum period began (100 days time for 50,000 signatures Art. 141 FC). On January 17, 2013, the signatures were submitted by the referendum committee.[7] The Federal Chancellery announced on February 19, 2013, that the referendum had taken place with 77,360 valid signatures.[8] The referendum then took place on September 22, 2013, in which the opponents of the law were defeated and the law was accepted by the people with 60.00%.[9] The law entered into force on January 1, 2016.

Results

| Canton | Yes (%) | No (%) | Participation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zurich | 60,5 % | 30,5 % | 49,28% |

| Bern | 54,9 % | 45,1 % | 44,77 % |

| Lucerne | 59,5 % | 40,5 % | 47,56 % |

| Uri | 49,5 % | 50,5 % | 44,85 % |

| Schwyz | 45,5 % | 54,5 % | 49,67 % |

| Obwalden | 51,4 % | 48,6 % | 49,71 % |

| Nildwalden | 56,1 % | 43,9 % | 50,00 % |

| Glarus | 51,3 % | 48,7 % | 38,27 % |

| Zug | 57,4 % | 42,6 % | 50,35 % |

| Fribourg | 66,0 % | 34,00 % | 46,59 % |

| Solothurn | 58,3 % | 41,7% | 45,04 % |

| Basel-Stadt | 67,7 % | 32,3 % | 47,15 % |

| Basel-Landschaft | 62,3 % | 44,13 % | 44,12 % |

| Schaffhausen | 50,0 % | 50,0 % | 63,71 % |

| Appenzell Ausserrhoden | 44,9 % | 55,1 % | 50,66 % |

| Appenzell Innerrhoden | 46,0 % | 54,0 % | 41,10 % |

| St. Gallen | 50,6 % | 49,4 % | 45,89 % |

| Grisons | 55,8 % | 44,2 % | 43,08 % |

| Aargau | 55,9 % | 44,1 % | 47,41 % |

| Thurgau | 50,3 % | 49,7 % | 45,54 % |

| Ticino | 64,4 % | 35,6 % | 46,96 % |

| Vaud | 73,6 % | 26,4 % | 45,99 % |

| Valais | 61,9 % | 38,1 % | 47,53 % |

| Neuchâtel | 67,0 % | 33,0 % | 42,74 % |

| Geneva | 77,8 % | 22,2 % | 47,48 % |

| Jura | 59,5 % | 40,5 % | 36,67 % |

| Swiss Confederation | 60,0 % | 40,0 % | 46,76% |

Application during the COVID 19 pandemic

On 25 February 2020, the first confirmed case of Sars Cov-2 infection was reported in Switzerland. Based on Art. 6 para. 2 let. b, the Federal Council issued the Ordinance of 28 February 2020 on Measures to Control the Coronavirus (COVID-19) on 28 February 2020. With this ordinance, it banned public and private events where more than 1000 people are present at the same time. Likewise, on March 13 of the same year, the Federal Council issued an ordinance based on the Epidemics Act. Unlike the first one, this one had its legal basis not only in the Epidemics Act, but directly in the Federal Constitution; it was thus an emergency ordinance, and the first one (an independent ordinance). On March 16, it classified the situation in Switzerland as exceptional. On the basis of two motions (20.3168 and 20.3144), the Federal Council was instructed to draw up the legal basis necessary for the introduction of the Covid 19 app[12] and to submit it to parliament for approval. It proposed to urgently amend the Epidemics Act, which the Federal Assembly accepted. The amendment entered into force on June 27, 2020, and will expire on June 30, 2022.[13]

On September 25, 2020, the Federal Assembly passed the Federal Law on the Legal Basis for Ordinances of the Federal Council to Address the COVID-19 Epidemic (Covid-19 Law),[14] declared it urgent, and enacted it on September 26, 2020.

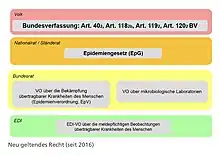

Constitutionality and delegation

The most important constitutional basis for the Epidemics Act is Art. 118 para. 2 FC letter b. This states: "It [the Federal Council] shall issue regulations on the control of communicable, widespread or malignant diseases of humans and animals."The characteristics mentioned (transmissible, highly prevalent or malignant) do not have to be fulfilled cumulatively, but only alternatively. Art. 118 para. 3 letter b, however, does not say anything about the state instruments for combating said diseases. In this context, control does not only mean preventive health measures, but also preventive or health-promoting measures. Because provisions on genetically modified pathogens were included in the revision of the Epidemics Act of 21 December 1995, the Epidemics Act also includes Art. 119 para. 2 and Art. 120 para. 2 of the Federal Constitution, which deal precisely with this subject. Art. 40 para. 2 forms the basis for measures in favor of Swiss citizens living abroad.

The Epidemics Act contains delegation norms for the issuance of dependent ordinances, in other words, certain legislative powers are delegated from the legislative to the executive branch unless they are excluded by the Federal Constitution (Art. 164 para. 2 FC). These delegations concern regulations whose details would substantially exceed the degree of concretization at the legislative level. Constitutionally, delegation powers must be limited to a specific subject of regulation, i.e. they may not be unlimited. In the Epidemics Act, for example, this concerns the obligation to report, which itself cannot be comprehensively laid down in the law because it is subject to scientific progress.

References

- "Botschaft zur Revision des Bundesgesetzes über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG)". Bundesblatt (in Swiss High German). Bundeskanzlei. pp. 17–18. Retrieved 2022-05-07.

- Gesetzgebung Übertragbare Krankheiten – Epidemiengesetz (EpG). Retrieved 2022-05-07 (Mit weiterführenden Dokumenten).

- "Botschaft zur Revision des Bundesgesetzes über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG)". Bundesblatt. Bundeskanzlei. Retrieved 2022-05-07.

- "Bundesgesetz vom 18. Dezember 1970 über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz)". Bundesblatt. Bundeskanzlei. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- "Verhandlungen" (PDF). Curia Vista. Parlamentsdienste. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- "Gesetzgebung Übertragbare Krankheiten – Epidemiengesetz (EpG)". Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- Bundeskanzlei BK. "Bundesgesetz über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG) Chronologie". Politische Rechte. Bundeskanzlei. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- "Referendum gegen das Bundesgesetz vom 28. September 2012 über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG). Zustandekommen". Bundesblatt. Bundeskanzlei. 2013-02-19. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- "Bundesratsbeschluss über das Ergebnis der Volksabstimmung vom 22. September 2013 (Volksinitiative «Ja zur Aufhebung der Wehrpflicht»; Bundesgesetz über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen [Epidemiengesetz, EpG]; Änderung des Bundesgesetzes über die Arbeit in Industrie, Gewerbe und Handel [Arbeitsgesetz, ArG])". Bundesblatt. Bundeskanzlei. 2013-11-18. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- "Epidemiengesetz". swissvotes.ch. Institut für Politikwissenschaft der Universität Bern. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- "Vorlage Nr. 573 Resultate in den Kantonen". Bundeskanzlei. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- "Botschaft zu einer dringlichen Änderung des Epidemiengesetzes im Zusammenhang mit dem Coronavirus (Proximity-Tracing-System)". Bundesblatt. Bundeskanzlei. 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- "Die Bundesversammlung und die Covid-19-Krise: Ein chronologischer Überblick" (PDF). parlament.ch (in Swiss High German). Parlamentsdienste. 2021-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- SR 818.102 Bundesgesetz über die gesetzlichen Grundlagen für Verordnungen des Bundesrates zur Bewältigung der COVID-19-Epidemie (Covid-19-Gesetz)