Erfurt Union

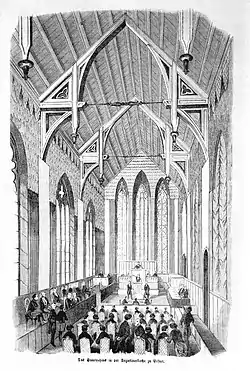

The Erfurt Union (German: Erfurter Union) was a short-lived union of German states under a federation, proposed by the Kingdom of Prussia at Erfurt, for which the Erfurt Union Parliament (Erfurter Unionsparlament), officially lasting from March 20 to April 29, 1850, was opened at the former Augustinian monastery in Erfurt.[1][2] The union never came into effect, and was seriously undermined in the Punctation of Olmütz (November 29, 1850; also called the Humiliation at Olmütz) under immense pressure from the Austrian Empire.

The Erfurt Union Erfurter Union | |

|---|---|

| 1849–1850 | |

Proposed reichskriegsflagge of the Erfurt Union. | |

March/April 1850: states that had MPs elected in the Erfurt Parliament (yellow), states part of the Four Kings Alliance (Dark red) | |

| History | |

• Established | 1849 |

• Disestablished | 1850 |

Conception of the Union

In the Revolutions of 1848, the Austrian-dominated German Confederation was dissolved, and the Frankfurt Assembly sought to establish new constitutions for the multitude of German states. The effort, however, ended in the Assembly's collapse, after King Frederick William IV refused the German crown. The Prussian government, under the influence of General Joseph Maria von Radowitz, who sought to unite the landed classes against the threat to Junker domination, seized the opportunity to initiate a new German federation under the leadership of the Hohenzollern monarch. At the same time, Frederick William IV acceded to his people's demands for a constitution, also agreeing to become leader of a united Germany.

A year before the convention of the Erfurt Union Parliament, on May 26, 1849, the Alliance of the Three Kings was concluded between Prussia, Saxony and Hanover, the latter two of which explicitly made the reservation of departure unless all other principalities with the exception of Austria joined. From this treaty sprung the Prussian policy of fusion, and thence the ambition of the Erfurt Union, which in its constitution abandoned universal and equal franchise in favour of the traditional three-class franchise. The constitution itself, however, was only to come into effect after revision and ratification by an elected Reichstag, as well as approval by the participating governments. 150 former liberal deputies to the German national assembly had acceded to the draft at a meeting in Gotha on June 25, 1849, and by the end of August 1849, almost all (twenty-eight) principalities had recognised the Reich constitution and joined the union, due in varying degrees to Prussian pressure.

Inceptive problems

Despite this, elections to the Erfurt parliament, held in January 1850, received very little popular support, or even recognition. Democrats universally boycotted the election, and with electoral participation below 50%, Saxony and Hanover exercised their reservation to leave the Alliance of Three Kings. No government in the end agreed to the constitution, and even though the document was readily accepted by the Gotha Party (incidentally narrowly defeated in the elections), it never took effect. The Erfurt parliament never materialised.

Meanwhile, Austria, having overcome its difficulties – the fall of Metternich, the abdication of Ferdinand I, and constitutional revolts in Italy and Hungary – began a renewed active resistance against Prussia's union plan. The Saxon and Hanoverian withdrawals from their alliance with Prussia can also be attributed in part to Austrian encouragement. Vienna contemplated restoration of the German Confederation recalling the German Diet, and rallied the Prussian nobility and feudal-corporate and anti-national groups around the Prussian General Ludwig Friedrich Leopold von Gerlach to increasingly successfully oppose Union policy.

In Prussia itself, a congress of princes held in Berlin in May 1850 explicitly decided against the merits of introducing a constitution at the point in time. Following the Prussian king's (and his ministers') weakening volition for German unification, Radowitz's influence declined. Prussia's union policy was further weakened by Austrian urges for the restoration of the Federal Assembly in Frankfurt in September the same year.

Autumn crisis of 1850

The Prussia–Austria conflict worsened by autumn that year, as disagreements over the question of federal executions in Holstein (dispute with Denmark) and the Electorate of Hesse almost escalated into a military conflict. Since 1848 the Austrians had been allied with the Russian Empire; after the Berlin government refused Austrian demands at the Warsaw Conference of October 28, 1850, the souring relations degenerated further on Prussia's November 5 announcement that it was mobilising its army and preparing for war, in response to troops of the German Confederation advancing into the Electorate of Hesse. War was avoided when Prussian leaders closely associated with the nobility threw their support behind Gerlach with the Prussian Conservative Party , known informally as the Kreuzzeitungspartei after the Kreuzzeitung newspaper, which supported Austria in advocating a return to the Confederation.

On November 29, 1850, the Punctation of Olmütz was concluded between Austria and Prussia with Russian participation. The treaty, seen by many as a humbling capitulation on Prussia's part to the Viennese Hofburg, saw Prussia submitting to the Confederation, reversing tack to demobilise, agreeing to partake in the intervention of the German Diet in Hesse and Holstein and renouncing any resumption of her union policy, and hence abandoning the Erfurt Union.

References

- Blackbourn, David (1997) The Long Nineteenth Century: A History of Germany, 1780-1918, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Gunter Mai, [2000] Die Erfurter Union und das Erfurter Unionsparlament 1850. Köln: Böhlau