Erpetonyx

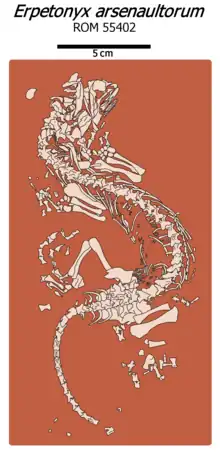

Erpetonyx is an extinct genus of bolosaurian parareptile from the Gzhelian stage of the Carboniferous period, with a single known species: Erpetonyx arsenaultorum. It is known from a single articulated and mostly complete specimen from Prince Edward Island in Canada. Phylogenetics has predicted that parareptiles first evolved in the Carboniferous, parallel to eureptiles ("true reptiles"). However, Hylonomus, the oldest eureptile known from fossil evidence, lived millions of years before parareptiles appeared in the fossil record. The discovery of Erpetonyx helped to shorten this gap between parareptile and eureptile fossils, as Erpetonyx lived in the Late Carboniferous and is one of the oldest known parareptiles (though Carbonodraco is now known to be older). However, it was not closely related to ancestral parareptiles, so its discovery also indicated that the initial diversification of parareptiles occurred earlier in the Carboniferous. Erpetonyx was a small reptile, with the entire skeleton about 20 to 25 centimeters (7.9 to 9.8 inches) in length.[1][2] It was likely carnivorous, and could be characterized by a variety of skeletal features, including a relatively elongated body and large claws with powerful tendon attachment points.[1]

| Erpetonyx Temporal range: Gzhelian (Late Pennsylvanian), | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of the holotype fossil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Parareptilia |

| Order: | †Procolophonomorpha |

| Clade: | †Bolosauria |

| Genus: | †Erpetonyx Modesto et al., 2015 |

| Type species | |

| †Erpetonyx arsenaultorum Modesto et al., 2015 | |

Discovery

Erpetonyx is known from a single specimen, a remarkably well-preserved skeleton, designated ROM 55402. This specimen hailed from Cape Egmont, in southwestern Prince Edward Island, Canada, in rock layers of the Edgmont Bay Formation that preserves fossils that date back to Gzhelian stage of the Carboniferous period. The specimen was discovered by nine-year-old Michael Arsenault in 2003 who was on vacation with his family at the time.[2] It was acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in 2004, and later rep.[2] Cape Breton University's Sean Modesto, a paleontologist and expert in ancient reptiles, was the lead author of a 2015 article published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, The team, which included researchers from the ROM, University of Toronto and the Smithsonian Institution, described and named the new genus and species, the first parareptile known from Carboniferous period fossils.[1]

The name Parareptilia was identified by the American zoologist, Olson (1910-1993), in 1947[3] and Bolosauria was identified by Oskar Kuhn in 1959.[4] Erpetonyx arsenaultorum was described and named by Modesto et al. in 2015. It is the closest relative of bolosaurids.[1]

Description

The skull was crushed and partially eroded, but some features (like the tooth row) were preserved well enough to be informative. The teeth were sharp, conical, and slightly curved. They gradually decreased in size towards the rear of the skull. Some broken teeth reveal that they had an internal structure of folded dentine, formally known as plicidentine. Plicidentine was once considered to characterize "labyrinthodont" amphibians such as temnospondyls, but it is now known to occur in some extinct amniotes as well. The supratemporal bones at the rear of the skull roof formed small horns, and the palate (roof of the mouth) was covered in small cones known as denticles. Denticles reached almost as far back in the mouth as the large, robust quadrate bones which formed the upper part of the jaw joint. Preserved portions of the braincase were generally similar to those of other reptiles, with the exception of a large opening (likely for the hyomandibular branch of the facial nerve) at the front edge of the base of the braincase.[1]

The body was relatively elongated compared to other parareptiles. There were 5 cervical (neck) vertebrae and 24 dorsal (torso) vertebrae. This leads to a total of 29 presacral (pre-hip) vertebrae, while other parareptiles typically had 26 or fewer. The presacrals were hourglass-shaped when seen from above and tightly connected to each other by means of large, rounded zygapophyses (joint plates). They gradually increased in length and width towards the hip. There were three sacral (hip) vertebrae, although only the first two had large, flared ribs which connected to the ilia (upper hip plates). 20 caudal (tail) vertebrae were also attached to the skeleton, along with a disconnected string of 13 from the tip of the tail and 10 isolated caudals. Estimating from the length of missing portions of the tail, there may have been 58 caudal vertebrae in total.[1]

The forelimbs were generally similar to those of other early reptiles. The humerus (upper arm bone) was slightly longer than the ulna and radius (lower arm bones). The knobs and joints forming the elbow were poorly developed, meaning that Erpetonyx may have had more flexible forelimbs than its contemporaries. The hand was incomplete, and some the carpals (wrist bones) were large while others were unusually small. On the other hand, the unguals (claws) were long and sharply pointed, with robust flexor tubercules (tendon attachment bumps). Some of the hip bones were obscured by the rest of the skeleton, but the ischium (rear lower plate) was longer than the pubis (front lower plate). The femur (thigh bone) was twisted, with the knee joints offset at 45 degrees from the rest of the shaft. In other early reptiles, this angle of torsion was smaller, usually 10 to 30 degrees. The slender tibia and fibula (lower leg bones) were shorter than the femur. The tarsals (ankle bones) were much more robust than the carpals, but also more disarticulated. The fourth metatarsal was the longest bone of the foot, and it was unusually expanded near the toe. The ungual of the fourth toe was tall, curved, and sharply pointed. Other toe claws were longer and lower. Nevertheless, all of the toe claws were longer than the other phalanges (toe bones).[1]

References

- Modesto, S. P.; Scott, D. M.; MacDougall, M. J.; Sues, H.-D.; Evans, D. C.; Reisz, R. R. (2015). "The oldest parareptile and the early diversification of reptiles". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1801): 20141912. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.1912. PMC 4308993. PMID 25589601.

- Chung, Emily (13 January 2015). "Fossil found by P.E.I. boy fills gap in reptile evolution: Lizard-like animal named after Michael Arsenault of Prince County, P.E.I." CBC News. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Olson, Everett Claire (1947). Roy, Sharat Kumar (ed.). "The family Diadectidae and its bearing on the classification of reptiles". Geology. Fieldiana. Chicago: Chicago Natural History Museum. 11 (1): 1–53. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.3579. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- Kuhn, Oskar (1959). "Die Ordnungen der fossilen 'Amphibien' und 'Reptilien'". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie: 337–347.