Danes

Danes (Danish: danskere, pronounced [ˈtænskɐɐ]) are an ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark.[27] This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 7 million

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,996,980[1] | |

| 1,430,897[2] | |

| 207,470[3][4] | |

| 52,510[5] | |

| 50,413[6] | |

| 50,000[7] | |

| 52,000[8][9][10] | |

| 48,000[11][12] | |

| 42,602[13] | |

| 18,493 (Danish born only)[14] | |

| 10,000[15] | |

| 7,000[16] | |

| 4,251[17] | |

| 4,214[18] | |

| 3,507[19] | |

| 2,084[20] | |

| 1,528[21] | |

| 1,281[22] | |

| 809[23] | |

| 500[24] | |

| 400[25] | |

| Languages | |

| Danish | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheranism (Church of Denmark)[26] Further details: Religion in Denmark | |

Danes generally regard themselves as a nationality and reserve the word "ethnic" for the description of recent immigrants,[28] sometimes referred to as "new Danes".[29] The contemporary Danish national identity is based on the idea of "Danishness", which is founded on principles formed through historical cultural connections and is typically not based on racial heritage.[30]

History

Early history

Denmark has been inhabited by various Germanic peoples since ancient times, including the Angles, Cimbri, Jutes, Herules, Teutones and others.[31] The first mentions of "Danes" are recorded in the mid-6th century by historians Procopius (Greek: δάνοι) and Jordanes (danī), who both refer to a tribe related to the Suetidi inhabiting the peninsula of Jutland, the province of Scania and the isles in between. Frankish annalists of the 8th century often refer to Danish kings. The Bobbio Orosius from the early 7th century distinguishes between South Danes inhabiting Jutland and North Danes inhabiting the isles and the province of Scania.

Viking Age

The first mention of Danes within Denmark is on the Jelling Rune Stone, which mentions the conversion of the Danes to Christianity by Harald Bluetooth in the 10th century.[32] Between c. 960 and the early 980s, Bluetooth established a kingdom in the lands of the Danes, stretching from Jutland to Scania. Around the same time, he received a visit from a German missionary who, by surviving an ordeal by fire according to legend, convinced Harold to convert to Christianity.[33]

The following years saw the Danish Viking expansion, which incorporated Norway and England into the Danish North Sea Empire. After the death of Canute the Great in 1035, England broke away from Danish control. Canute's nephew Sweyn Estridson (1020–74) re-established strong royal Danish authority and built a good relationship with the archbishop of Bremen, at that time the archbishop of all Scandinavia. Over the next centuries, the Danish empire expanded throughout the southern Baltic coast.[31] Under the 14th century king Olaf II, Denmark acquired control of the Kingdom of Norway, which included the territories of Norway, Iceland and the Faroese Islands. Olaf's mother, Margrethe I, united Norway, Sweden and Denmark into the Kalmar Union.[31]

Denmark–Norway

In 1523, Sweden won its independence, leading to the dismantling of the Kalmar Union and the establishment of Denmark–Norway. Denmark–Norway grew wealthy during the 16th century, largely because of the increased traffic through the Øresund. The Crown of Denmark could tax the traffic, because it controlled both sides of the Sound at the time.

The Reformation, which originated in the German lands in the early 16th century from the ideas of Martin Luther (1483–1546), had a considerable impact on Denmark. The Danish Reformation started in the mid-1520s. Some Danes wanted access to the Bible in their own language. In 1524, Hans Mikkelsen and Christiern Pedersen translated the New Testament into Danish; it became an instant best-seller. Those who had traveled to Wittenberg in Saxony and come under the influence of the teachings of Luther and his associates included Hans Tausen, a Danish monk in the Order of St John Hospitallers.

In the 17th century Denmark–Norway colonized Greenland.[31]

After a failed war with the Swedish Empire, the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658 removed the areas of the Scandinavian peninsula from Danish control, thus establishing the boundaries between Norway, Denmark, and Sweden that exist to this day. In the centuries after this loss of territory, the populations of the Scanian lands, who had previously been considered Danish, came to be fully integrated as Swedes.

In the early 19th century, Denmark suffered a defeat in the Napoleonic Wars; Denmark lost control over Norway and territories in what is now northern Germany. The political and economic defeat ironically sparked what is known as the Danish Golden Age during which a Danish national identity first came to be fully formed. The Danish liberal and national movements gained momentum in the 1830s, and after the European revolutions of 1848 Denmark became a constitutional monarchy on 5 June 1849. The growing bourgeoisie had demanded a share in government, and in an attempt to avert the sort of bloody revolution occurring elsewhere in Europe, Frederick VII gave in to the demands of the citizens. A new constitution emerged, separating the powers and granting the franchise to all adult males, as well as freedom of the press, religion, and association. The king became head of the executive branch.

Identity

Danishness (danskhed) is the concept on which contemporary Danish national and ethnic identity is based. It is a set of values formed through the historic trajectory of the formation of the Danish nation. The ideology of Danishness emphasizes the notion of historical connection between the population and the territory of Denmark and the relation between the thousand-year-old Danish monarchy and the modern Danish state, the 19th-century national romantic idea of "the people" (folk), a view of Danish society as homogeneous and socially egalitarian as well as strong cultural ties to other Scandinavian nations.[34]

As a concept, det danske folk (the Danish people) played an important role in 19th-century ethnic nationalism and refers to self-identification rather than a legal status. Use of the term is most often restricted to a historical context; the historic German-Danish struggle regarding the status of the Duchy of Schleswig vis-à-vis a Danish nation-state. It describes people of Danish nationality, both in Denmark and elsewhere–most importantly, ethnic Danes in both Denmark proper and the former Danish Duchy of Schleswig. Excluded from this definition are people from the formerly Norway, Faroe Islands, and Greenland; members of the German minority; and members of other ethnic minorities.

Importantly, since its formulation, Danish identity has not been linked to a particular racial or biological heritage, as many other ethno-national identities have. N. F. S. Grundtvig, for example, emphasized the Danish language and the emotional relation to and identification with the nation of Denmark as the defining criteria of Danishness. This cultural definition of ethnicity has been suggested to be one of the reasons that Denmark was able to integrate their earliest ethnic minorities of Jewish and Polish origins into the Danish ethnic group with much more success than neighboring Germany. Jewishness was not seen as being incompatible with a Danish ethnic identity, as long as the most important cultural practices and values were shared. This inclusive ethnicity has in turn been described as the background for the relative lack of virulent antisemitism in Denmark and the rescue of the Danish Jews, saving 99% of Denmark's Jewish population from the Holocaust.[35]

Modern Danish cultural identity is rooted in the birth of the Danish national state during the 19th century. In this regard, Danish national identity was built on a basis of peasant culture and Lutheran theology, with Grundtvig and his popular movement playing a prominent part in the process. Two defining cultural criteria of being Danish were speaking the Danish language and identifying Denmark as a homeland.[36]

The ideology of Danishness has been politically important in the formulation of Danish political relations with the EU, which has been met with considerable resistance in the Danish population, and in recent reactions in the Danish public to the increasing influence of immigration.[37][38]

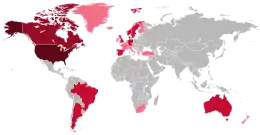

Diaspora

The Danish diaspora consists of emigrants and their descendants, especially those who maintain some of the customs of their Danish culture. A minority of approximately fifty thousand Danish-identifying German citizens live in the former Danish territory of Southern Schleswig (Sydslesvig), now located within the borders of Germany, forming around ten percent of the local population. In Denmark, the latter group is often referred to as "Danes south of the border" (De danske syd for grænsen), the "Danish-minded" (de dansksindede), or simply "South Schleswigers". Due to immigration there are considerable populations with Danish roots outside Denmark in countries such as the United States, Brazil, Canada, Greenland and Argentina.

Danish Americans (Dansk-amerikanere) are Americans of Danish descent. There are approximately 1,500,000 Americans of Danish origin or descent. Most Danish-Americans live in the Western United States or the Midwestern United States. California has the largest population of people of Danish descent in the United States. Notable Danish communities in the United States are located in Solvang, California, and Racine, Wisconsin, but these populations are not considered to be Danes for official purposes by the Danish government, and heritage alone can not be used to claim Danish citizenship, as it can in some European nations.

According to the 2006 Census, there were 200,035 Canadians with Danish background, 17,650 of whom were born in Denmark.[3][39] Canada became an important destination for the Danes during the post war period. At one point, a Canadian immigration office was to be set up in Copenhagen.[40]

In Greenland, a self-governing territory under Danish sovereignty, there are approximately 6,348 Danish Greenlanders making up roughly 11% of the territory's population.[41]

References

- "Find statistics – Statistics Denmark". Dst.dk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada – Data table". 2.statcan.ca. 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "Ethnic Origin, both sexes, age (total), Canada, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data". Canada 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 20 February 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Statistics Norway. "Persons with immigrant background by immigration category, country background and sex. 1 January 2009 (Immigrants and Norwegian-norn to immigrant parents + Other immigrant background)". Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- "Improved access to historical census data". Censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Archived 24 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "World Migration | International Organization for Migration". Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Sá, Carlos Augusto Trojaner de. "Por uma busca de dinamarqueses no Brasil: um estudo de caso inicial" (PDF). Revista do Historiador. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- "Reportagens". revistagloborural.globo.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016.

- Flott, Søren (2020). Rejsen mod syd. Historien om de danske udvandrere til Argentina. Lindhardt og Ringhof. p. 315. ISBN 978-8711906675. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- Archived 16 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tabeller over Sveriges befolkning 2005" (PDF). Scb.se. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "UK | Born Abroad | Denmark". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "Global Migration Map: Origins and Destinations, 1990–2017". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- Gynther Adolphsen. "6000–7000 danskere bor ved den franske Riviera – Frankrig". Udvandrerne.dk. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "Hvor mange dansker bor i udlandet". Statsborger.dk. 28 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- "Population by country of birth, sex and age 1 January 1998-2022". Statistics Iceland. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- Archived 24 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Danesi in Italia – statistiche e distribuzione per regione". Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "Sefstat" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Archived 12 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit und Geburtsland". www.statistik.at. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Kent Dahl. "500 danskere i Tokyo – Japan". Udvandrerne.dk. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Archived 23 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Fler lämnade kyrkan i Danmark Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine 3.1.2015 Kyrkans tidning

- Christopher Muscato (2018). "Denmark Ethnic Groups". University of Northern Colorado. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Jeffrey Cole (2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-59884-302-6. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Jorgen Nielsen (2011). Islam in Denmark: The Challenge of Diversity. Lexington Books. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-7391-7013-7. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "Denmark Demographics". WorldAtlas. 31 August 2018. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 211–213

- "daner | Gyldendal - Den Store Danske". Denstoredanske.dk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Adam of Bremen, History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen, trans. Francis J. Tschan (New York, 2002), pp. 77–78.

- Jenkins, Richard. "The limits of identity: ethnicity, conflict, and politics" (PDF). The University of Sheffield. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Yael Enoch. 1994. The intolerance of a tolerant people: Ethnic relations in Denmark. Ethnic and Racial Studies. Volume 17, Issue 2, 1994

- Østergård, Uffe, Peasants and Danes: The Danish National Identity and Political Culture. Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Jan., 1992), pp. 3–27

- Lise Togeby (1998). "Prejudice and tolerance in a period of increasing ethnic diversity and growing unemployment. Denmark since 1970". Ethnic and Racial Studies, 21, 6: 1137–115

- Jens Rydgren. 2010. Radical Right-wing Populism in Denmark and Sweden: Explaining Party System Change and Stability. Volume 30, Number 1, Winter–Spring 2010

- "Statistics Canada : 2006 Census Topic-based tabulations". Statcan.ca. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Bender, Henning. Danish emigration to Canada

- "CIA – The World Factbook – Greenland". CIA. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

Sources

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.

External links

![]() Media related to Danes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Danes at Wikimedia Commons